(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2018-2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

In 1970 the epicenter of the contemporary art world was the stretch of sleek galleries on 57th Street in Manhattan. Having just graduated from Hartford Art School, I secured a job as a gallery assistant at the legendary Sidney Janis Gallery, just a half block from Tiffany’s. The gallery represented many renowned artists, including Hans Arp, Piet Mondrian, Ellsworth Kelly, and Claes Oldenburg, among others.

My first assignment was to install an exhibition by artist Josef Albers. About two dozen paintings on Masonite panels arrived from Albers’s studio. Each piece employed variations on Albers’s series of colorful receding squares. When I turned over one of the panels I noticed the name of each tube of paint was listed in black marker. I learned that Albers never mixed colors but instead collected tubes of paint from around the world and applied them directly with a palette knife. As a new employee, I was anxious to make a good impression and to hang the show precisely. Once done, I proudly showed my work to Sidney Janis. He stared at each wall and said, “People are not as short as you and I. Rehang that wall of small paintings above eye level.” Naturally, I did as I was told.

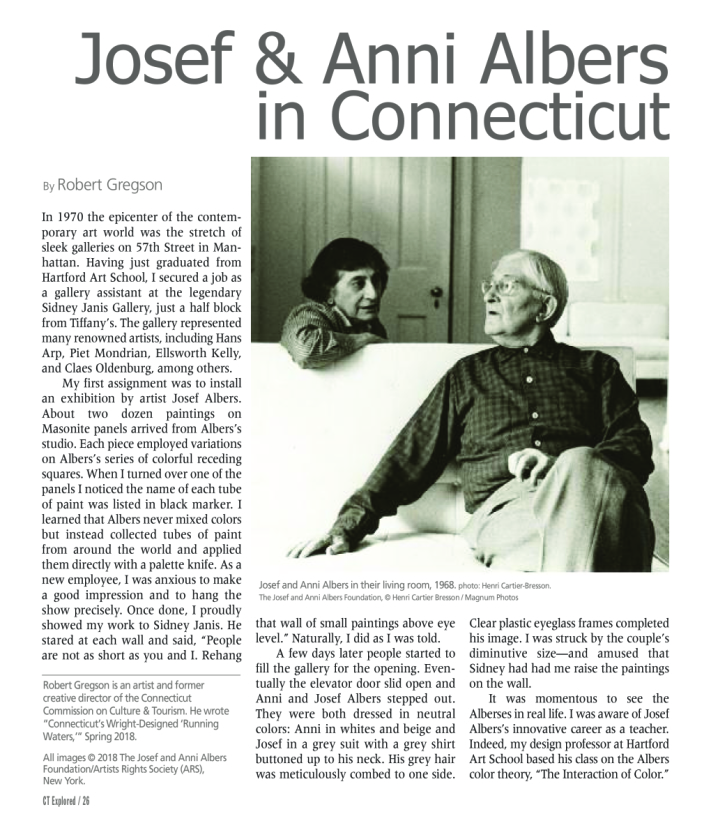

A few days later people started to fill the gallery for the opening. Eventually the elevator door slid open and Anni and Josef Albers stepped out. They were both dressed in neutral colors: Anni in whites and beige and Josef in a grey suit with a grey shirt buttoned up to his neck. His grey hair was meticulously combed to one side. Clear plastic eyeglass frames completed his image. I was struck by the couple’s diminutive size—and amused that Sidney had had me raise the paintings on the wall.

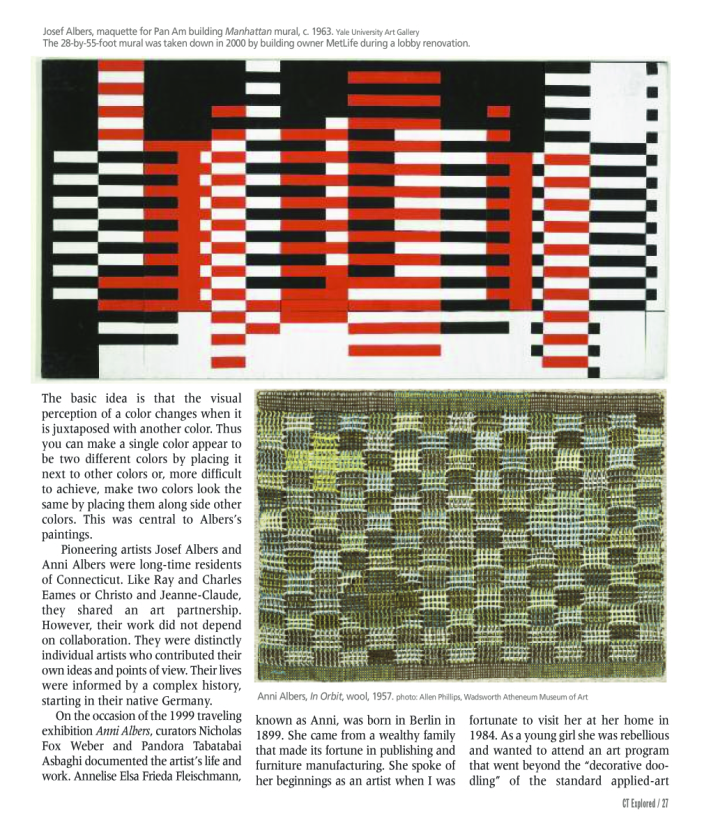

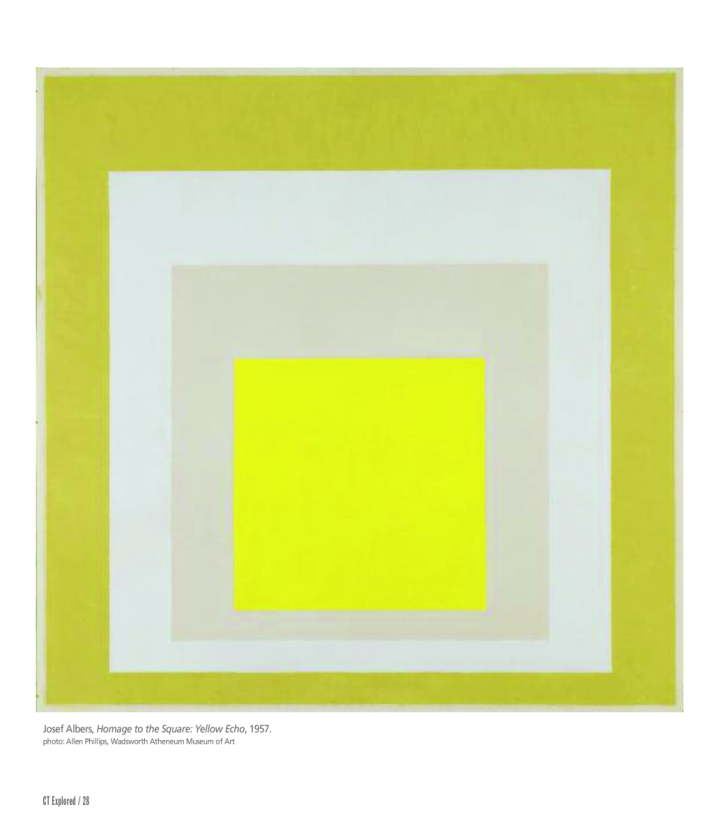

It was momentous to see the Alberses in real life. I was aware of Josef Albers’s innovative career as a teacher. Indeed, my design professor at Hartford Art School based his class on the Albers color theory, “The Interaction of Color.” The basic idea is that the visual perception of a color changes when it is juxtaposed with another color. Thus you can make a single color appear to be two different colors by placing it next to other colors or, more difficult to achieve, make two colors look the same by placing them along side other colors. This was central to Albers’s paintings.

Pioneering artists Josef Albers and Anni Albers were long-time residents of Connecticut. Like Ray and Charles Eames or Christo and Jeanne-Claude, they shared an art partnership. However, their work did not depend on collaboration. They were distinctly individual artists who contributed their own ideas and points of view. Their lives were informed by a complex history, starting in their native Germany.

Pioneering artists Josef Albers and Anni Albers were long-time residents of Connecticut. Like Ray and Charles Eames or Christo and Jeanne-Claude, they shared an art partnership. However, their work did not depend on collaboration. They were distinctly individual artists who contributed their own ideas and points of view. Their lives were informed by a complex history, starting in their native Germany.

On the occasion of the 1999 traveling exhibition Anni Albers, curators Nicholas Fox Weber and Pandora Tabatabai Asbaghi documented the artist’s life and work. Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann, known as Anni, was born in Berlin in 1899. She came from a wealthy family that made its fortune in publishing and furniture manufacturing. She spoke of her beginnings as an artist when I was fortunate to visit her at her home in 1984. As a young girl she was rebellious and wanted to attend an art program that went beyond the “decorative doodling” of the standard applied-art schools. The Bauhaus offered her the challenge she wanted. Her father needed convincing, but he eventually relented. Although she was not accepted to the school at first, she applied a second time, and in 1922 she succeeded. She confessed, “It was really quite difficult to get in because out of 16 students only 4 were admitted.” Despite the school’s support of gender equality, women were encouraged to take less physically demanding classes. These included bookbinding, pottery, and textiles. She quickly discovered that she was not cut out for metalwork, carpentry, or wall painting, so there were not many options left. Despite the feeling that pursuing textiles was not serious enough, she gave weaving a try. It was fate.

Josef Albers (1888 –1976) was born in Bottrop, a small mining town in Germany. He met Anni in 1922 when both were students at the Bauhaus school. He was 11 years older than her. During my visit she remembered meeting Josef. “He was a co-student––an older student––and as in many schools you have an admiration for the older students—sometimes more than the teacher, even. And so we gradually met and I showed him a lot of what I was doing and we took a walk and we developed a relationship gradually.” They were married in 1925, the same year the school moved from Weimar into the new glass-walled Bauhaus building designed by Walter Gropius in Dessau. The Alberses moved into their new, spare quarters—the flat-roofed, planar Masters’ Houses. Photographs of their living room in Josef + Anni Albers: Designs for Living (Merrell, 2004) feature prototypes of Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair plus furniture designed by Josef positioned rigidly against the walls. The Zen-like, restrained Bauhaus aesthetic became part of their style for the rest of their lives.

Three years after Anni and Josef married, Josef became the first Bauhaus student appointed to the faculty, joining such artists as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, Herbert Bayer, and others who had a major impact on 20th-century culture. In the beginning Josef experimented with glass and decorative arts in addition to painting. He also designed objects and furniture. Anni worked in the weaving program and took classes with Paul Klee, who quickly became her artistic hero. It is in this period of the Bauhaus that the Alberses formulated their philosophy for art and life: to reduce living to a level of simplicity—shedding any excess—and making every decision an aesthetic choice. As stated in Designs for Living, they lived and breathed art as the lifeblood of their existence.

Josef was associated with the Bauhaus longer than any other artist. Then, in 1933 everything came to a halt when the Nazis padlocked the doors and closed the school. Anni said that anyone connected with the Bauhaus was considered a leftist. She continued, “Things were becoming violent.” To make matters more stressful, Anni was Jewish. Josef was a Catholic. Like many members of the Bauhaus, they wanted to emigrate to the United States, but in order to leave Germany, they needed the assurance of a job in America. Arrangements were made with the help of Philip Johnson, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art who had visited them in Germany, and Johnson’s fellow curator Eddie Warburg, whose wealthy family financed their voyage. (The Warburg family home later became the Jewish Museum on 5th Avenue in New York City.) Johnson and Warburg helped to secure positions for the Alberses at the newly created Black Mountain College in Ashville, North Carolina. Although Josef had a limited grasp of English, he was given a job as professor of art. Anni was appointed assistant professor of art. She recalled, “I was asked to develop a weaving department, and Josef was asked to teach art in any form he wanted.”

In North Carolina Josef continued to expand his skills as a teacher and Anni started to become increasingly fascinated by weaving, bringing an experimental approach and inventive handling of materials to her work. Josef developed an entirely new way to teach art. He did not focus on techniques, styles, or rules but rather went directly to the core visual elements: line, shape, color, and texture. This approach provided his students with the tools to personalize their form of expression.

Despite his being a talented teacher, some students felt Josef was not easy to get along with. Mary Emma Harris, in The Arts at Black Mountain College(MIT Press, 1987), includes students’ reports that he had an authoritarian manner and was dogmatic, though not doctrinaire. Robert Rauschenberg felt that “Albers was a beautiful teacher and impossible person… He wasn’t easy to talk to and I found his criticism so excruciating and so devastating that I never asked for it. Years later though I am still learning what he taught me.”

The Alberses stayed at Black Mountain College for 16 years, until 1949, when they disagreed with changes in the direction of the school and resigned. During the next year they traveled to Mexico, and Josef became a visiting professor at the Cincinnati Art Academy and Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. Anni was granted a one-person show at the Museum of Modern Art arranged by Philip Johnson––the first solo exhibition for a textile artist. In 1950, at age 62, Josef was offered the chairmanship of the department of design at Yale University. He and Anni bought a small, Cape Cod-style house in New Haven. This reflected their Bauhaus philosophy of simple, stripped-down, mass produced, and off-the-rack living. He began his groundbreaking “Homage to the Square” series, which occupied him for the rest of his remaining 26 years. He called his works “platters to serve color.” At first Anni was baffled by Josef’s new direction. She shared with me, “I was surprised that these squares were interesting to people because I couldn’t understand it at first. Sometimes you don’t see it. It takes an outsider when you are so close.”

In 1950, at age 62, Josef was offered the chairmanship of the department of design at Yale University. He and Anni bought a small, Cape Cod-style house in New Haven. This reflected their Bauhaus philosophy of simple, stripped-down, mass produced, and off-the-rack living. He began his groundbreaking “Homage to the Square” series, which occupied him for the rest of his remaining 26 years. He called his works “platters to serve color.” At first Anni was baffled by Josef’s new direction. She shared with me, “I was surprised that these squares were interesting to people because I couldn’t understand it at first. Sometimes you don’t see it. It takes an outsider when you are so close.”

Josef had a profound effect on architects, artists, and designers at Yale. Many of his students became world famous, while Albers remained in the background. It wasn’t until 1965, when Josef was included in The Responsive Eye, a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, that he began to get worldwide recognition for his work on visual perception and color.

This success afforded the Alberses financial security. They purchased a slightly larger house, a standard raised ranch on a quiet street in Orange, a suburb of New Haven. The couple’s minimalist spirit was evident in the landscaping of their yard. They refused to have any foundation plantings, so the lawn extended directly up to the base of the house. Nicholas Fox Weber describes in Anni Albers (Guggenheim Museum, 1999)that Anni and Josef treated themselves to the luxury of a green Mercedes 240, even though they typically spurned symbols of affluence. Both of them liked to drive. They would drive to the post office past the town cemetery. There they bought a plot and placed their headstones facing the narrow cemetery driveway so after one died the other could visit without leaving the car.

According to Neal David Benezra in The Murals and Sculpture of Josef Albers(Garland, 1985), Josef began collaborating with his fellow Yale faculty member, the architect King-Lui Wu. Wu sought out Albers, who had experimented with geometric designs in brick in a 1950 commission from Gropius, who by then was at Harvard University. Based on that work, Wu and Albers both agreed that a fireplace could become a major sculptural element in residential architecture. As a result, Josef designed two fireplace relief sculptures with off-white firebrick, one for the Irving Rouse House in North Haven and another in the Benjamin DuPont House in Woodbridge. He also designed the “hidden” logo embedded in the white brick wall of the Manuscript Secret Society at Yale. Josef also received commissions to design album covers, tableware, furniture, and other objects, while Anni created textiles and graphics for architectural interiors.

Both Anni and Josef had remarkable careers during the several decades that they lived and worked in Connecticut. In 1971 Josef became the first living artist ever to have a major retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He designed many works of public art and received many honorary degrees.

In 1970 Anni gave up weaving altogether in favor of printmaking. She tired of the time it took to create one piece. Printmaking opened up a new chapter in her career. In 1983 she created a portfolio of nine prints called Connectionsthat represent images from a lifetime of work. During these years she began to exhibit regularly and was honored with degrees, honorary doctorates, and awards from many institutions. In 1976 her life changed again when Josef died at age 88. She then became responsible for his legacy in addition to her own work.

The Alberses had established the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation in 1971, as its website states, to further “the revelation and evocation of vision through art.” After Josef’s death, Nick Weber became the organization’s executive director. In the 1990s the Albers Foundation purchased a woodland site in Bethany, Connecticut and built a study center designed by Josef’s former student, sculptor/architect Tim Prentice. Much of the funding for this project was received by Anni as restitution for the loss of family property in the former East Berlin during World War II.

In 1984 Weber arranged for me to visit Anni at her home at 808 Birchwood Drive in Orange. I was interested in seeing her prints and of course was eager to speak with her. Despite her confinement to a wheel chair, she was still vital. I was struck by the starkness of the house. Except for four paintings by Josef, there was no color anywhere. Harkening back to their Bauhaus residence, the austere living room, dining room, and kitchen were all white. The living-room seating was covered with white Naugahyde instead of one of Anni’s fabrics. She disliked having her art displayed in the house, she told me. She had a small studio in one of the three bedrooms.

In 1984 Weber arranged for me to visit Anni at her home at 808 Birchwood Drive in Orange. I was interested in seeing her prints and of course was eager to speak with her. Despite her confinement to a wheel chair, she was still vital. I was struck by the starkness of the house. Except for four paintings by Josef, there was no color anywhere. Harkening back to their Bauhaus residence, the austere living room, dining room, and kitchen were all white. The living-room seating was covered with white Naugahyde instead of one of Anni’s fabrics. She disliked having her art displayed in the house, she told me. She had a small studio in one of the three bedrooms.

Her fame attracted pilgrimages to her modest home by notables such as Jackie Kennedy Onassis and John Cage. Photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson and Lord Snowdon photographed her and Josef. Anni’s close friend, actor and director Maximilian Schell made her a movie star by including her as a credited cast member in his 1984 documentary Marlene, about Marlene Dietrich.

At the end of her life Anni retained strong feelings about being an artist. “I’ve never called myself an artist. Josef and I always felt that art is something you are aiming at, but you aren’t an artist because of that. You do your work, whatever it is, and so he called himself a painter and I called myself a weaver but we never called ourselves artists. We thought that belonged to the gods.” Anni died in 1994 at age 94. She and Josef are buried in Orange—their headstones situated side by side. She was the last surviving teacher from the Bauhaus.

Robert Gregson is an artist and former creative director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism. He wrote “Connecticut’s Wright-Designed ‘Running Waters,’” Spring 2018.

Explore!

Winter 2009-2010: Modernism in Connecticut

Winter 2004-2005: Connecticut’s Art History 101

Winter 2006-2007: Connecticut’s Art History 102