(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2008/2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

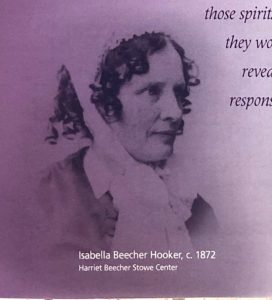

On a cold January morning in 1877, Isabella Beecher Hooker feverishly wrote in her diary. For a year Hooker had anticipated the fulfillment of startling revelations including the onset of the Millennium (a thousand-year period described in the Bible’s Book of Revelations) and her own crucial role in that phenomenon. Now she sat evaluating her spiritualist beliefs. She concluded that though some of her spirit-guide prophecies were inaccurate, she was still receiving valuable guidance from those spirits and that they would ultimately reveal her responsibilities to her.

Although the term “spiritualism” conjures images of floating furniture, clairvoyants, and unscrupulous frauds, spiritualism’s historical significance is less about sensational claims or charlatans than about the many of its practitioners who were inspired to become advocates of social reform. At its best, spiritualism was part of a large movement in which people grappled with new interpretations of faith, health, and community, and slowly – and sometimes reluctantly – reevaluated the meanings of democracy and civil rights. Proponents of social justice saw spiritualism’s emphasis on the equal value of individuals as a call to action.

Although the term “spiritualism” conjures images of floating furniture, clairvoyants, and unscrupulous frauds, spiritualism’s historical significance is less about sensational claims or charlatans than about the many of its practitioners who were inspired to become advocates of social reform. At its best, spiritualism was part of a large movement in which people grappled with new interpretations of faith, health, and community, and slowly – and sometimes reluctantly – reevaluated the meanings of democracy and civil rights. Proponents of social justice saw spiritualism’s emphasis on the equal value of individuals as a call to action.

Most 19th-century reformers embraced spiritualism. Spiritualist members of the famous Blackwell family, for instance, included abolitionists and women’s rights advocates Henry and Samuel as well as Elizabeth and Emily, two of the country’s first female doctors. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was also quick to adopt spiritualism. At the close of her life in 1893, suffragist Lucy Stone stated she would “know it on the other side” when suffrage came. More locally, Hartford’s Nook Farm neighborhood, home to abolitionists, women’s rights activists, health reformers, and educators, was filled with spiritual investigators. This intellectually vibrant and curious neighborhood met for séances, discussed mediums and clairvoyants over dinners, and exchanged letters about spiritualism. Chief among Nook Farm’s spiritualists were abolitionist and women’s rights supporter John Hooker and Isabella Beecher Hooker. Isabella was a founding member and one-time president of the national Woman’s Suffrage Association and founding member of the Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Association.

“Raps on Midnight Tables”

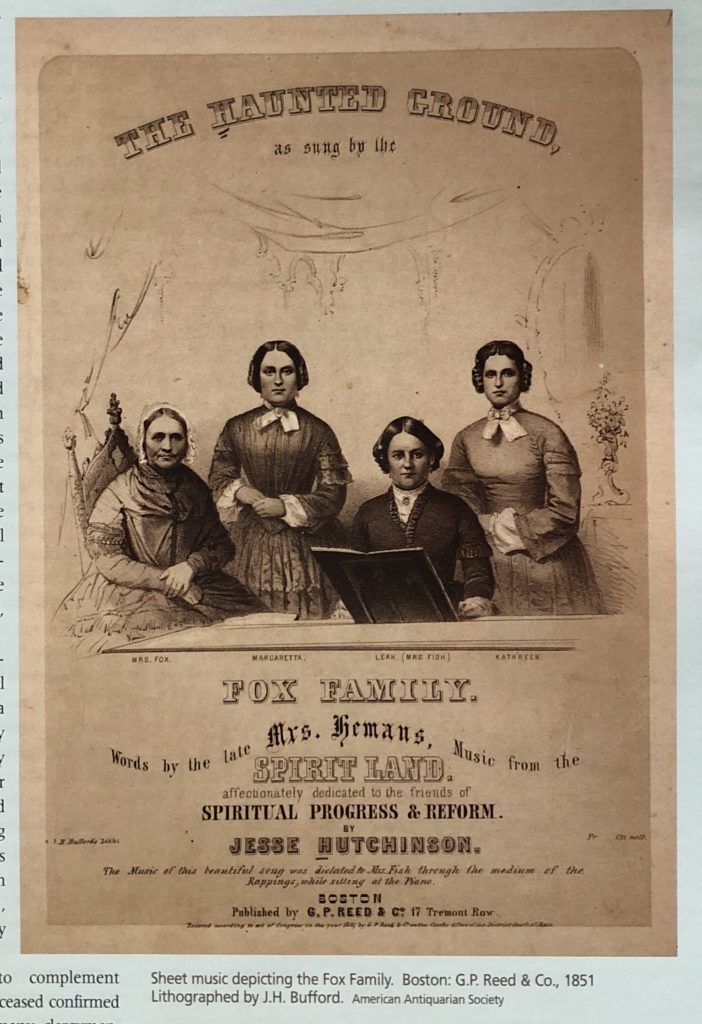

Spiritualism’s origins are generally traced to two young sisters from New York. In 1848, the relatives and neighbors of the Hydeville Fox family began hearing rapping on the furniture and walls of the family farmhouse whenever they were with 12-year-old Kate Fox and her sister, 14-year-old Margaret. The noises had no apparent physical source yet responded to specific queries. News soon spread that the sisters were vehicles, or mediums, for spirits. Family members suspected the rapping was caused by the ghost of a salesman who had been murdered in the vicinity; they feared the noises might be harmful in some way. For their safety, the Fox girls were sent to live with their older sister in nearby Rochester. But the percussive sounds followed them.

Rochester, New York was in the heart of the so-called “burned over district,” a designation that reflected the religious out-pourings and political passions that had erupted and raced through the area like wildfires during the first half of the 19th century. The place was a hotbed of both religious and secular radical thought and activity, ranging from the origins of the Church of Latter Day Saints and the Seventh Day Adventists to the birth of the dress-reform movement (which introduced “bloomers” to the world). Abolitionists and temperance advocates thrived here. And in Seneca Falls, the world’s first women’s rights convention gathered in 1848 – the same year the Foxes heard their first messages. Many of those calling upon the Fox sisters were Hicksite Quakers, a radical sect that believed God directly inspired individuals to correct social ills. Four of the five organizers of the Seneca Falls convention, for example, were Hicksite Quakers.

When Rochester’s Hicksite community welcomed the Fox girls, the leading social activists of the day suddenly encountered a new belief that, while embryonic, clearly reinforced and enhanced their previously held convictions. In 1852, Hicksite Quaker and Fox supporter Isaac Post published Voices From the Spirit World. It was not long before spiritualism burned its way across New York and the rest of the country. When the nation entered the Civil War in 1861, spiritualism was primed to comfort many who were soon to lose loved ones.

At first spiritualism seemed to complement Christianity. Communication with the deceased confirmed the notion of a spiritual afterlife, and many clergymen including members of the influential Beecher family (which included eight ministers), embraced it. Soon, though, the new faith – and it was considered a faith both by its supporters and its detractors – moved beyond traditional Christianity. Spiritualism refuted the belief in infant damnation, judgement day, and especially Hell. Instead, spiritualism described the after-life as a set of spheres of understanding, each greater than the one before, through which spirits passed. All souls, regardless of their religious beliefs, continued their spiritual growth after death, and the souls of children matured and grew in wisdom. Spirits were free to visit the land of the living at any time and continued to guard and guide those they loved.

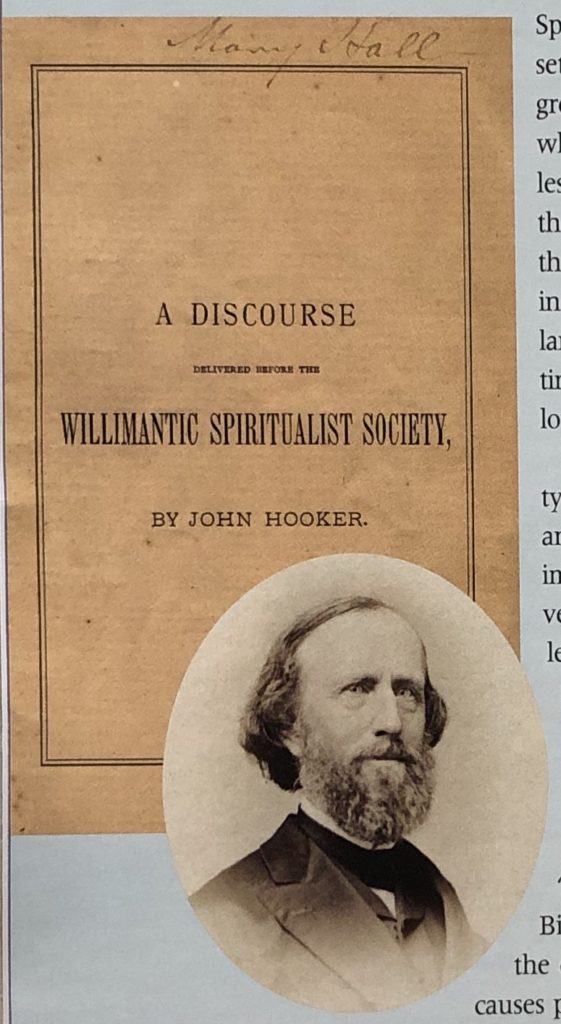

top: A Discourse by John Hooker, March 21, 1886; bottom: John Hooker, c. 1869. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

At a time of high infant mortality and war, inclusive salvation and angel children made the new faith immensely appealing, albeit not universally accepted. Skeptics doubted the legitimacy of spirit contacts, or manifestations, and feared their potential influence. Lydia Maria Child, anti-slavery advocate and author of The American Frugal Housewife (1828), worried that spiritualism was “undermining the authority of the Bible in the minds of what are called the common people faster than all other causes put together.” Ralph Waldo Emerson, titular head of the intellectual Transcendental Movement, referred to spiritualists as part of the “shallow Americanism which hopes to get rich by credit, [and]to get knowledge by raps on midnight tables.” But spiritualism’s accessibility contributed to its appeal. Within months of the revelation of the Fox girls’ experiences, thousands of individuals gathered in parlors, seeking contact with their own spirit guides.

Several factors encouraged spiritualism’s widespread acceptance. The most influential were an ongoing movement toward more liberal theologies, the widespread longing to ease the pain of bereavement through personal communication with the dead, and a growing popular interest in scientific methodology that demanded empirical or physical evidence.

An important element of more progressive theologies involved recasting children as innocents as opposed to being born in sin. Spiritualism went further than Christianity in assuring grieving parents their little ones would be loved and would continue to grow intellectually and spiritually. Popular authors Charles Dickens and Harriet Beecher Stowe depicted fictional children dying as pure spirits, but the real grief surrounding childhood death made the comfort offered by spiritualism a welcome solace. When Stowe’s 18-month-old son Charlie died of cholera his mother famously equated her “crushing grief” to that of enslaved mothers whose children were stolen from them. Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) was Stowe’s catharsis. In contrast, Charlie’s father, Calvin, found consolation in the thought that the spirit of Eliza Tyler Stowe, his late, childless, first wife, would care for his small son in heaven. Repeated epidemics such as the one that killed Charlie Stowe and the carnage of the Civil War increased the number of those needing comfort; nearly every family mourned someone.

Today it might seem contradictory for spiritualism to be viewed as a scientific approach to faith. But in the 19th century, spiritualism promised visible and audible proof of the soul. Those interested in spiritualism were called investigators, a term that reinforced its scientific claims. Spirit messages were not supposed to be accepted as a matter of faith. Investigators listened to the evidence supplied by mediums and determined its validity for themselves.

In contrast to other persuasions, spiritualists believed that spirit contact was accessible to everyone. This egalitarianism had striking consequences for women, who were discouraged or barred from religious leadership roles elsewhere. Furthermore, the tenet of individualism that was fundamental to spiritualism encouraged believers to speak out against those who sought to control others.

“Getting yourself right”: The Spirit of Reform

Mainstream newspapers including The Hartford Courant ran articles and editorials discussing the pros and cons of spiritualism, but it was publications such as Great Harmonia (1850) by Andrew Jackson Davis, Spiritual Manifestations (1853,1879) by Charles Beecher, and the weekly newspaper The Banner of Light that defined the movement.

Spiritualism’s loose structure makes it problematic to say all spiritualists believed one thing or another, but the movement adhered to two critical tenets: an emphasis on the value of individuality, or the equal value of each soul or person, and the idea that after death people entered spheres of spirituality based on the degree to which they had respected the individuality of others while they had been alive. Spiritualism simultaneously helped ease the grief of those who mourned and challenged people to improve their spiritual futures by reforming earthly life. As a result, spiritualists assumed major leadership roles in all reform movements, especially in abolition and women’s rights, working against what spiritualists regarded as attempts by one group of people to suppress individuality and to “own the souls” of others.

“The only religious sect in the world that has recognized the equality of women is spiritualism,” wrote women’s rights leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Spiritualism offered women opportunities to expand their roles as leaders without overtly confronting 19th-century expectations. Women who sought careers outside the domestic sphere or lobbied for political rights openly challenged social norms, but mediums were usually less assertive. They were, after all, only speaking on behalf of others and comforting the bereaved. But as mediums, even women reluctant to speak in public gained authority as the voices through which angels advised and living sought solace.

Notorious reformers such as Victoria Woodhull, who promoted women’s suffrage and the end of the sexual double standard, along with slightly less controversial reformers such as Francis Burr of Connecticut, credited their spirit guides as the force behind their voices. Spiritualism also provided opportunity for women to speak freely under cover of their spirit contacts. In 1878, Hartford suffragist and medium Isabella Beecher Hooker reordered in her diary a vibrant conversation with her husband, John Hooker. John had told Isabella he should have been firmer in silencing her public opinions regarding her brother Henry Ward Beecher’s guilt during Beecher’s adultery trial. Isabella credited her response to Catharine Beecher, her recently deceased (and notoriously bossy) sister, telling John he “will have to get over [controlling others]in the next life, & it will be easier to begin here.” Isabella continued, “Sister C. … advises you to begin at once, or you will have a hard time getting yourself right, as she does.” Hooker may have been using her sister’s spirit to scold her husband, but the words underscored a spiritualist precept: Stop suppressing the individuality of others now, or spend time in the next life “getting yourself right.”

Connecticut Seers

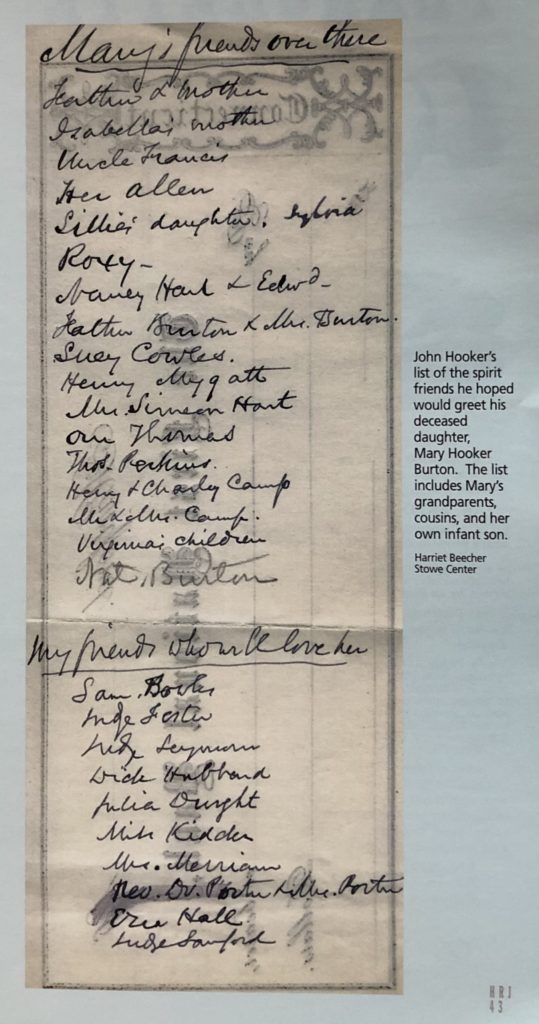

John Hooker’s list of the spirit friends he hoped would greet his deceased daughter, Mary Hooker Burton. The list includes Mary’s grandparents, cousins, and her infant son. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

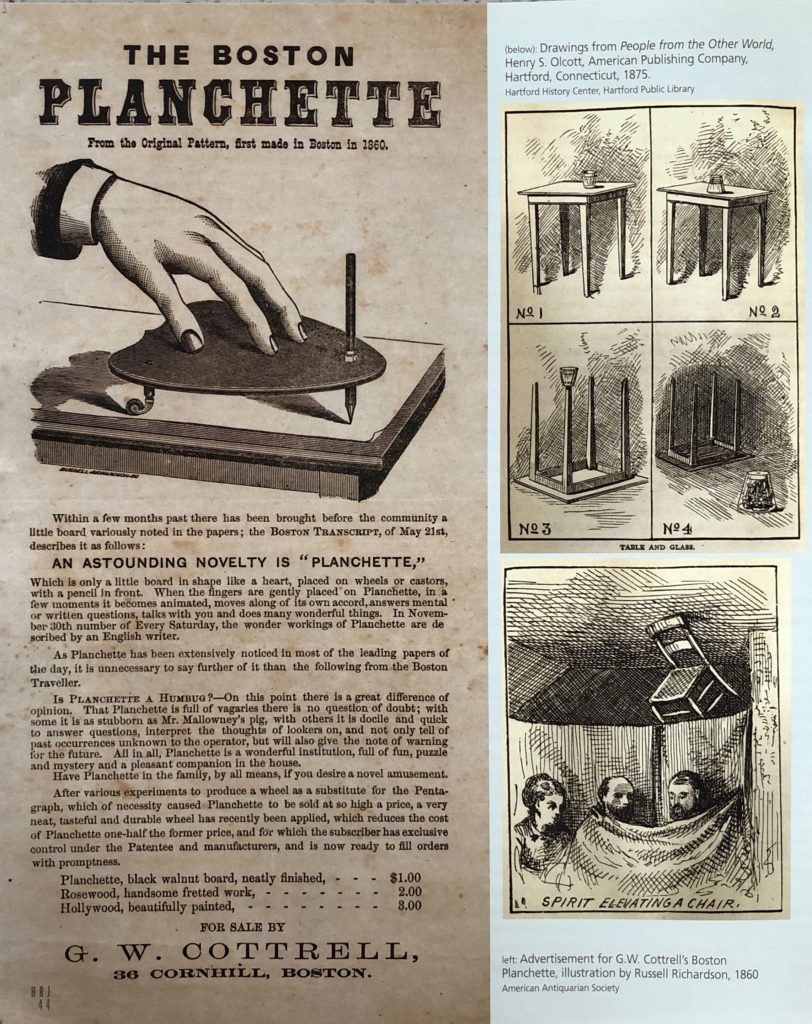

Many Nook Farm residents investigated spiritualism. Ultimately, they came to differing conclusions. Calvin Stowe had had visions since his childhood, decades before spiritualism captivated the nation. He never doubted the reality of his experiences. Publisher George Warner and his wife Lily, future preservationist Katharine Seymour Day, and author Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) and his wife Olivia all attended séances but did not express the convictions of the Hookers. Clemens’s need to test mediums caused Isabella Hooker to question his open-mindedness. Harriet Beecher Stowe attended investigations, referenced manifestations in her novels, and experimented with the planchette (a small, heart-shaped plank with castors on two feet and a pencil on the third that was used to facilitate spirit writings). Though comforted by purported messages from her drowned son Henry Ellis, missing son Fred, and others, she ultimately decided that the only spirit guide for her was Christ. In an 1872 letter to author George Eliot, she wrote, “Do invisible spirits speak in any wise, — wise or foolish? — is the question… As I am a believer in the Bible and Christianity, I don’t need these things as confirmations… I regard them simply as I do the phenomena of the Aurora Borealis, or Darwin’s studies on natural selection, as curious studies into nature.”

In 1888, spiritualism suffered a crisis when an impoverished and now-middle-aged Margaret Fox sold her story to The New York World, explaining that she had caused those mysterious rappings by cracking toe joints – something her critics claimed since 1851. Many Spiritualist reformers abandoned the faith and joined Universalist and Unitarian churches or the newly established Church of Christian Science, which incorporated spiritual approaches to heath care while emphasizing anew a connection with Christianity. As a result, the spiritualism movement focused more on manifestations and less on individuals’ responsibility to reform. In response, some reformers downplayed their involvement in spiritualism.

True believers like the Hookers, however, remained unfazed; their spirituality had moved beyond the questionable rappings of a particular teenager. Though commenting two years before Margaret Fox’s confession, John Hooker spoke for many in his address to the Willimantic Spiritualist Society in 1886. “I believe in the reality of communication between the spirits of the departed and those of us who are still in earth life. There have undoubtedly been frauds, which all spiritualists condemn, and honest delusions, which all must deplore. But allowing for all these, there is left a great mass of phenomenon that …must be regarded as genuine.” Hooker went on to compare late 19th-century spiritualists to early abolitionists. “The church…is making a great mistake in denouncing spiritualism…It made the same mistake in its treatment of the early anti-slavery movement.”

In its early form, spiritualism helped women find their public voice by easing them beyond their traditional roles. When women became mediums, they unconsciously trained to become public leaders as they were initiated to public speaking first on behalf of others (spirits) and, later, as advocates for themselves. Connecticut mediums Isabella Beecher Hooker, Lita Barney Sayles, and Francis Ellen Burr all played important roles in the state’s women’s rights campaigns. Hooker in particular found strength to pursue her public advocacy for women’s rights when her spirit visions confirmed the importance of her work. Spiritualism fueled Hooker’s commitment to women’s rights and provided profound comfort as she received guidance from the mother she lost as a child, her daughter who died at age 39, and ultimately, her deceased husband of 60 years. Historically, the importance of spiritualism’s influence was less about where “invisible spirits speak” than about the drive to “getting yourself right.” Because of spiritualism, Americans promoted social reforms, and women boldly assumed leadership roles in religion and elsewhere as the nation redefined itself in the 19th century.

Dawn Adiletta was curator of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

Read More!

The Pine Grove Spiritualist Camp, Spring 2020

“Theodate Pope Riddle: Communicating with the Spirits,” Winter 2020-2021