by Briann Greenfield

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The converted Baptist church on Colchester’s Main Street out of which Arthur Liverant operates his family’s antiques business is crowded with examples of 18th- and 19th-century American design. Tall clocks, brass candlesticks, dressing tables, chests of drawers, paintings, portraits, needlework images, fancy chairs, and stately high chests stand ready to be discovered. Liverant specializes in fine examples of Connecticut and New England furniture and decorative arts created before 1840, the kind of furnishings that were made by hand and owned by elite families. They were desirable during the period of their construction and are strongly sought after today by collectors and antiques enthusiasts who value their craftsmanship, aesthetic quality, and connection to the past.

The converted Baptist church on Colchester’s Main Street out of which Arthur Liverant operates his family’s antiques business is crowded with examples of 18th- and 19th-century American design. Tall clocks, brass candlesticks, dressing tables, chests of drawers, paintings, portraits, needlework images, fancy chairs, and stately high chests stand ready to be discovered. Liverant specializes in fine examples of Connecticut and New England furniture and decorative arts created before 1840, the kind of furnishings that were made by hand and owned by elite families. They were desirable during the period of their construction and are strongly sought after today by collectors and antiques enthusiasts who value their craftsmanship, aesthetic quality, and connection to the past.

That Arthur loves his work and the objects he sells is apparent. He gushes when talking about a rare 18th-century landscape painting of Hebron and takes me on a short car ride to see the places depicted in the work and the gravesite of its original owner. When a woman brings a sampler into the shop to sell, Liverant and his associate Kevin Tulimieri use the occasion to educate her in the history of early American needlework. The two compare her piece to other examples in the shop and explain how materials, design, condition, and historical associations affect value in the marketplace.

But Arthur is not the first in his family to sell antiques, though the business model he employs would have received sharp criticism from his grandfather, Nathan Liverant, who founded the antiques concern in 1920 and whose name the business still bears. Buying and selling fine antiques is a complex trade that requires large capital outlays and a nuanced understanding of what collectors will pay. For example, one Queen Anne armchair can be worth thousands more than another simply on the basis of its proportions, and a dealer has to have the knowledge to recognize subtle variations in design. While Arthur now readily invests in the best-quality and most-desired antiques he can afford, his grandfather never trusted the antiques market and would not risk money on high-end wares.

That Nathan harbored a skeptical streak is not so surprising given the instability that marked his early life. While Arthur grew up in Colchester, surrounded by family and connected to his faith through the town’s well-established Jewish community, his grandfather was an immigrant who arrived at Ellis Island from Odessa, Russia in 1890 at the tender age of 11. It was a time of violence, when many Russian Jews were fleeing government-condoned pogroms, organized raids on Jewish communities that included killings and the destruction of property. Between 1881 and 1924, more than 2.5 million Jews arrived in America, but Nathan made the journey alone. His family put him on a boat with instructions to meet the person (whose relationship to the family the current Liverants don’t fully know) in New York City who would take care of him until the rest of his family arrived. His family never came, and the woman raised Nathan by herself.

In New York, Nathan started out in the furrier business. But he didn’t like the city. While helping a friend make a delivery to a rural coat factory, Nathan discovered the small town of Colchester. Like many Connecticut country towns, Colchester at the turn of the 20th century was losing its Yankee population as its old families abandoned their rocky farms for more profitable ventures in nearby cities and western lands. With cheap land and a small manufacturing center, the town became a destination for Jewish immigrants eager to escape the overcrowded conditions of New York’s Lower East Side and willing to try their hand at farming. These resettlement activities were funded in part by the Baron de Hirsch Fund in Germany and its U.S. subsidiary, the Jewish Agricultural Society, which offered future farmers lowinterest loans and farm education programs to assist with the transition. [For more on Jewish farming in Connecticut see “Hebrew Tillers of the Soil,” Spring 2006.] For Liverant, Colchester’s rural countryside and established Jewish community made it an attractive alternative to his New York life. And so, in an era in which the American Jewish experience was closely associated with an urban existence, Nathan Liverant packed up his belongings and moved with his young wife and son to rural Connecticut.

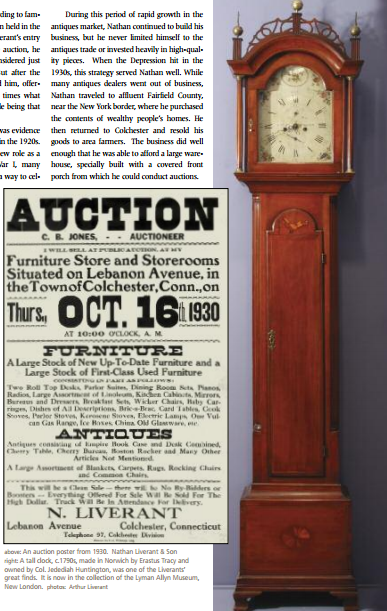

Liverant had no desire to become a farmer. Farming was hard, and starting an agricultural business without prior experience could only be classified as risky. So he set out performing odd jobs, transporting passengers to and from the Colchester railroad station, and selling used goods to his rural neighbors. According to family tradition, a small country auction held in the 1920s provided the catalyst for Liverant’s entry into the antiques business. At the auction, he won the bidding for what he considered just another old piece of furniture. But after the sale, another attendee approached him, offering to buy the article for several times what Liverant had just paid, his rationale being that it was an “antique.”

Liverant’s auction experience was evidence of the rising popularity of antiques in the 1920s. As the United States took on its new role as a global power following World War I, many Americans embraced antiquing as a way to celebrate their nation’s cultural heritage. Armed with the new technology of the automobile, antiques enthusiasts scoured the New England countryside, visiting smallruralshops and knocking on the doors of private residences in search of early American furniture and decorative arts. Department stores such as Wanamaker’s, Lord and Taylor, B. Altman, Marshall Field, and Jordan Marsh served collectors by establishing extensive antiques departments, while museums such asthe Metropolitan Museum of Art opened new galleries featuring period rooms adorned with early American household furnishings. All this interest was clearly reflected in the prices antiques garnered at auction. In 1929, at the watershed sale of the collection of the Philadelphia wool merchant and antiques collector Howard Reifsynder, a chest on chest known as the Van Pelt Highboy sold for the record price of $44,000 and a Philadelphia Chippendale armchair brought another $33,000. Such prices were nothing short of astonishing at a time when the average American income was just $1,405 a year.

During this period of rapid growth in the antiques market, Nathan continued to build his business, but he never limited himself to the antiques trade or invested heavily in high-quality pieces. When the Depression hit in the 1930s, this strategy served Nathan well. While many antiques dealers went out of business, Nathan traveled to affluent Fairfield County, near the New York border, where he purchased the contents of wealthy people’s homes. He then returned to Colchester and resold his goods to area farmers. The business did well enough that he was able to afford a large warehouse, specially built with a covered front porch from which he could conduct auctions.

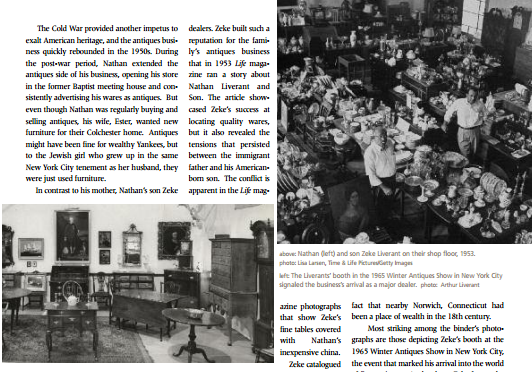

The Cold War provided another ipetus to exalt American heritage, and the antiques business quickly rebounded in the 1950s. During the post-war period, Nathan extended the antiques side of his business, opening his store in the former Baptist meeting house and consistently advertising his wares as antiques. But even though Nathan was regularly buying and selling antiques, his wife, Ester, wanted new furniture for their Colchester home. Antiques might have been fine for wealthy Yankees, but to the Jewish girl who grew up in the same New York City tenementas her husband, they were just used furniture.

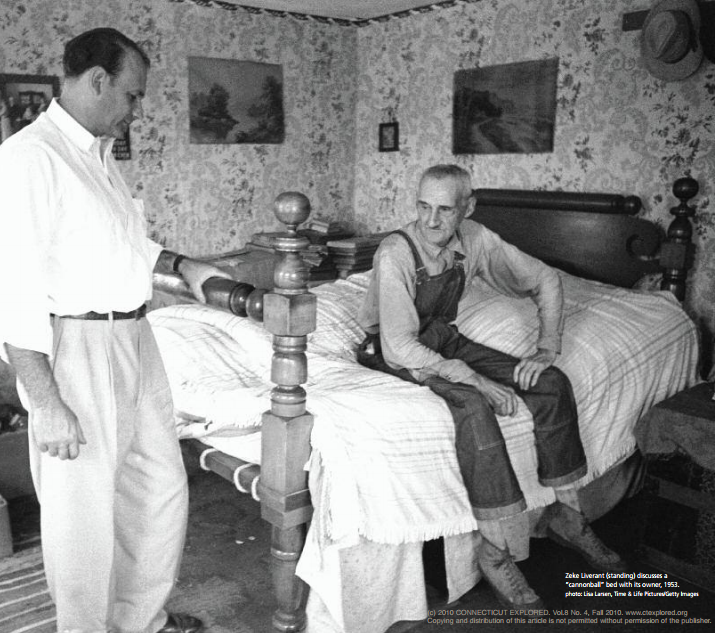

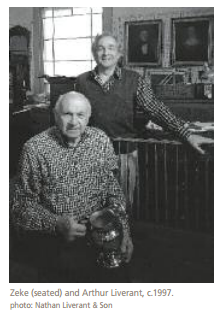

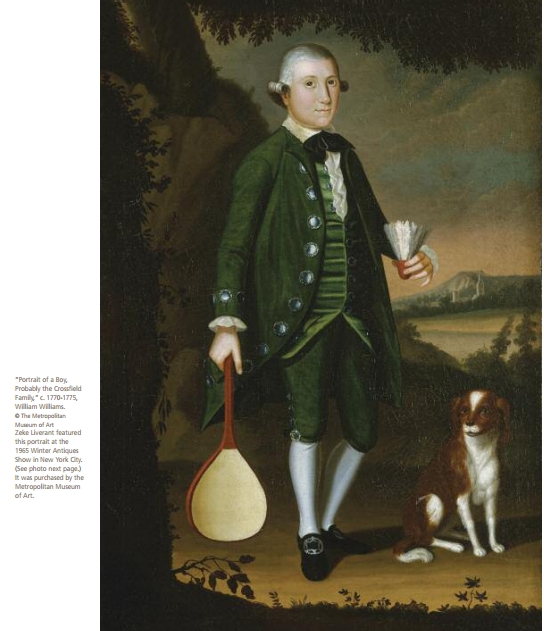

In contrast to his mother, Nathan’s son Zeke developed a real love for the furnishings of early America. Like his father decades before, Zeke learned the profit ability of antiques from a specific incident. According to his son Arthur, Zeke was a boy of about 12 when he located his first “find” among his father’s stock. The piece was an 18th-century silver muffineer, or sugar shaker. Young Zeke recognized the piece as similar to one he had seen in his father’s antiques books and asked if he could hold it for a dealer who specialized in antique silver. When the dealer arrived, he recognized the muffineer’s value to silver collectors and offered the boy $100, a price far in excess of what his father’s country customers would have paid and one that provided new shoes and clothes for everyone in the Liverant household. Zeke was hooked, and he began improving his family’s stock to compete with high-end antiques dealers. Zeke built such a reputation for the family’s antiques business that in 1953 Life magazine ran a story about Nathan Liverant and Son. The article show-cased Zeke’s success at locating quality wares, but it also revealed the tensions that persisted between the immigrant father and his American-born son. The conflict is apparent in the Life magazine photographs that show Zeke’s fine tables covered with Nathan’s inexpensive china. Zeke catalogued his antiquing triumphs in an old binder stuffed with photographs and secured by a coarse cotton rope that he called the book of “GreatFinds.” In it are photographs of a rare American-made high chest decorated with oriental inspired motifs on a black background, a late 18th-century musical tall clock with a label from the Massachusetts clockmaker Simon Willard, and a collection of exquisitely crafted needlework pieces stitched by Prudence Punderson of Preston, Connecticut in the 1770s, which now reside in the collections of the Connecticut Historical Society. [See the Explore! box below for information about where to see these pieces; for more information see “An 18th-Century View of the Stages of Life, ”Summer 2009.] In many cases, Zeke purchased such goods from the descendants of their original owners, a feat facilitated by the fact that nearby Norwich, Connecticut had been a place of wealth in the 18th century.

The Liverants were not alone as Jewish dealers in the antiques world. Tied to the junk trade, a favored occupation of immigrant Jewish entrepreneurs, the antiques business was not only open and accessible but a valuable way for new immigrants to assimilate in to American society. Other Connecticut Jewish antiques dealers included the Arons family of Ansonia and the Margolis family of Hartford, who sold and repaired antique furniture before starting a cabinet making business that specialized in antique reproductions. New York’s most famous antiques firm, Ginsberg and Levy, was started by a couple of Jewish junk dealers from Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Boston, too, had many Jewish dealers, including Israel Sack, who started out in the furniture repair business on Boston’s Beacon Hill and who rose to become one of the nation’s most prominent dealers.

The Liverants were not alone as Jewish dealers in the antiques world. Tied to the junk trade, a favored occupation of immigrant Jewish entrepreneurs, the antiques business was not only open and accessible but a valuable way for new immigrants to assimilate in to American society. Other Connecticut Jewish antiques dealers included the Arons family of Ansonia and the Margolis family of Hartford, who sold and repaired antique furniture before starting a cabinet making business that specialized in antique reproductions. New York’s most famous antiques firm, Ginsberg and Levy, was started by a couple of Jewish junk dealers from Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Boston, too, had many Jewish dealers, including Israel Sack, who started out in the furniture repair business on Boston’s Beacon Hill and who rose to become one of the nation’s most prominent dealers.

The presence of so many Jewish dealers meant both competition and community. When it came to securing particular pieces from area families, the Liverants often found themselves in competition with George and Benny Arons. The Liverants built a closer relationship with the Sack family. Zeke had a deep friendship with Israel Sack’s son Albert, himself an authority on early American furniture and well respected for his 1950 collecting treatise officially titled Fine Points of Furniture but popularly known to everyone in the field as “Good, Better, Best” for the way it illustrated differences in aesthetic quality among antique pieces.

As a business, the antiques trade was very hierarchical. At the bottom were the “pickers,” who operated without their own stores and who went door-to-door looking to secure antiques from private owners and to sell them to local shops. Next were mid-level dealers such as the Liverants, who might have access to high quality goods but who lacked a clientele to buy such expensive wares. As a mid-level dealer, Zeke typically sold his best finds to Albert, whose customers included elite collectors. But this hierarchy challenged the families’ relationship when Albert’s brother Harold advertised a Rhode Island china table as having been bought from descendants of its original owners by the Sacks when in fact Zeke had brought the piece to market. The family friendship survived, but it motivated Zeke to start developing his own customer base.

This year, the Liverant family celebrates its 90th year in business. From modest beginnings, the Liverants have built a reputation as promenent dealers in the field. Arthur has even appeared on PBS’s popular program Antiques Road show. But being an antiques dealer in the 21st century is not without its difficulties. Large auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s have gained power in the marketplace, making it hard for small, independent dealers to compete. At the same time, tastes among the collecting public are changing, and the field of early American decorative arts now faces competition from the rising popularity of mid-20th-century modern furniture—a new addition to the antiques market. With such challenges and a recession-plagued economy, one cannot help but wonder what advice Nathan Liverant, the immigrant who built a life for his family in America and who guided his business through the Great Depression, would have for today’s antiques dealers.

This year, the Liverant family celebrates its 90th year in business. From modest beginnings, the Liverants have built a reputation as promenent dealers in the field. Arthur has even appeared on PBS’s popular program Antiques Road show. But being an antiques dealer in the 21st century is not without its difficulties. Large auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s have gained power in the marketplace, making it hard for small, independent dealers to compete. At the same time, tastes among the collecting public are changing, and the field of early American decorative arts now faces competition from the rising popularity of mid-20th-century modern furniture—a new addition to the antiques market. With such challenges and a recession-plagued economy, one cannot help but wonder what advice Nathan Liverant, the immigrant who built a life for his family in America and who guided his business through the Great Depression, would have for today’s antiques dealers.

Briann Greenfield was an associate professor of history at Central Connecticut State University and a member of the Connecticut Explored editorial team. This story is based on her book Out of the Attic: Inventing Antiques in Twentieth Century New England (UMASS Press, 2009).