By Katherine Hermes and Alexandra Maravel

(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer 2023

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Haddam Island State Park (Thirty Mile Island) viewed from Haddam Meadows State Park, February, 2023. photo: Katherine Hermes

Even uninhabited river islands have stories that lie beneath their quiet, green surfaces. Haddam Island, known as “Thirty Mile Island” in the 17th and 18th centuries, is one such place. In fact, there are three layers to the story of this island: of place, of powerful Native women, and of abstract colonial authority.

The Island in the River

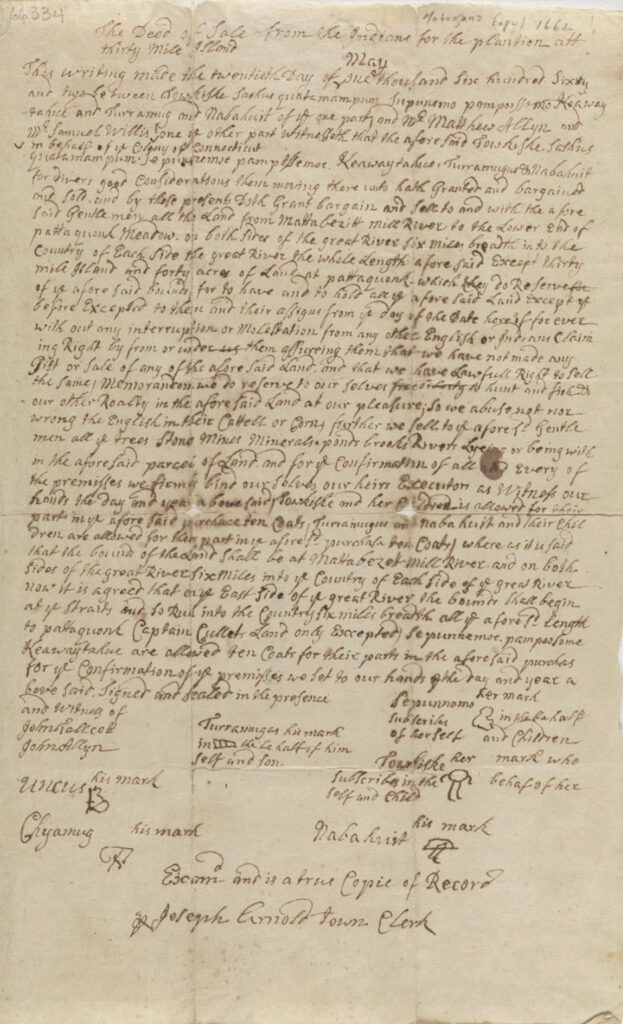

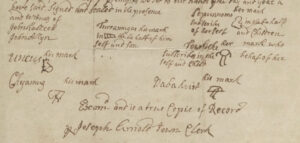

In May 1662 representatives of the Colony of Connecticut signed a deed with the male and female leaders of the Wangunk people reserving the 18-acre (now 14–acre) Thirty Mile Island for the exclusive use of the Wangunk. The island lay in the center of the Connecticut River about 10 miles downstream from Middletown. The English named it Thirty Mile Island, possibly for its distance from Hartford or for its (incorrectly) estimated distance from the sea. The colonists claimed for themselves a 100-plus-square-mile tract that included the town of Haddam and was known as Thirty Mile Island Plantation. The Wangunk also specifically retained hunting and fishing rights as far south as modern-day Chester, “with out any interruption or Molestation from any other English.”

In May 1662 representatives of the Colony of Connecticut signed a deed with the male and female leaders of the Wangunk people reserving the 18-acre (now 14–acre) Thirty Mile Island for the exclusive use of the Wangunk. The island lay in the center of the Connecticut River about 10 miles downstream from Middletown. The English named it Thirty Mile Island, possibly for its distance from Hartford or for its (incorrectly) estimated distance from the sea. The colonists claimed for themselves a 100-plus-square-mile tract that included the town of Haddam and was known as Thirty Mile Island Plantation. The Wangunk also specifically retained hunting and fishing rights as far south as modern-day Chester, “with out any interruption or Molestation from any other English.”

For Native people, hunting and fishing rights were important to retain, but rights to the island itself preserved areas essential for women’s food production. From the very first colonial incursions that threatened to claim Thirty Mile Island, Native people sought to retain it. A line of powerful Wangunk sunksquaws (the Southern New England Native term for chiefly female elders) tried to ensure the precious island would always belong to them and their heirs.

Thomas Wickman, in his article “Our Best Places: Gender, Food Sovereignty, and Miantonomi’s Kin on the Connecticut River,” Early American Studies, Spring 2021, explains that Wangunk women were responsible for providing plant-based food and medicine, and the river was integral to that work. Corn, beans, and squash–the three sisters–required regular tending between the planting in April and May and the harvesting in September. Then began processing of the corn and beans for storage and future consumption. Wangunk women relied on the shallow waters for edible and medicinal plants, while men fished in the deeper waters. In order to dispossess Native people, Wickman argues, the colonists sought to eliminate access to the places most essential for women’s food management.

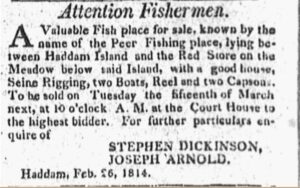

Peer Fishing place, Haddam Island. Middlesex Gazette, March 10, 1814. image: America’s Historical Newspapers.

European settlers began occupying land on the island in the mid-17th century, but their presence there was sporadic until the late 18th century. The fertile bottomland so valuable to the Native women was of less interest to the colonists than the other economic opportunities the island offered. Fishing companies employed men for haul-seining American shad that spawned around the island, while white farmers grazed cattle and planted crops. By the start of the 19th century there were no more Wangunk using the island. The Middlesex Gazette ran advertisements in 1814 for a “Peer Fishing” place “lying between Haddam Island and the Red Store on the Meadow below the Island.” The Baltimore Patriot and Berkshire Journal ran articles in May 1831 about fishermen who found a 120-pound fur seal while fishing for alewives there. The island eventually fell completely out of economic use.

The Island of Women’s Power

Sowheag, the grand sachem at the time of English and Wangunk contact, had many children. His sons became sachems, or chiefs, of towns up and down the Connecticut River, the original domain of the Wangunk. His eldest daughter, Wawarme, also known as Wawaloam, married the grand sachem of the Narragansetts, Miantonomi (who died in 1643). By the 1670s she had returned to live in the South Meadow of Hartford with her son Massescuppe and her people. Wawarme’s sisters, Sepunnomo and Towkishke, married and had families within their traditional homelands, Sepunnemo in Middletown and Towkishke in Haddam and Thirty Mile Island.

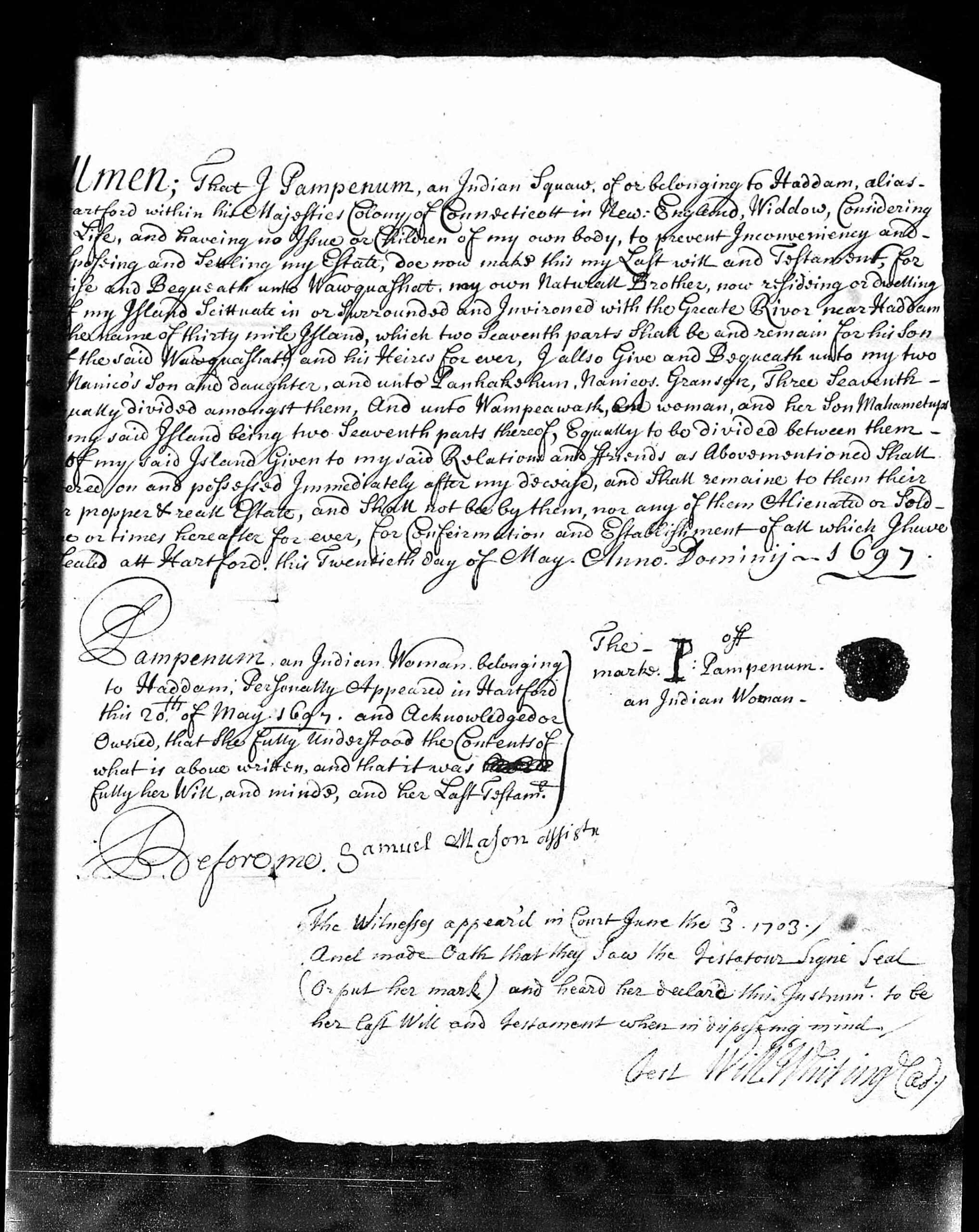

Towkishke’s sovereignty over Thirty Mile Island remained secure for a generation. Towkishke died sometime between 1693 and 1697, leaving her daughter Pampenum as the new sunksquaw of Thirty Mile Island. (Power passed from Towkishke to her daughter, not to her son Wawquashat.) Pampenum’s first cousin Sarah Onepenny (the Elder), daughter of Sepunnemo and Onepenny, was the sunksquaw of Middletown. While Pampenum was widowed and childless, Sarah Onepenny the Elder had three sons and two daughters. Pampenum had a brother and a nephew and dozens of cousins. Within this circle were Wampeawask, also known as Cheehums, the wife of Mahomet I, a grandson and heir of the Mohegan sachem Uncas, and her daughter Occoousque. These women formed a supportive female community committed to the ongoing effort to preserve Wangunk land.

A century later Native women would lose control of Thirty Mile Island. Let us begin at the sad end so we may finish with the mighty beginning of the tale.

The Island of Colonial Authority

By the 1790s, as the United States became a new nation, state courts became desolate places for Indigenous peoples. On January 6, 1789 the town of Guilford tallied its expense account for the late “Ann Indian,” also known as Ann Tantapan, an aged and ill Wangunk-Niantic woman who had required town support. During a four-year period Guilford spent £38 pounds, 8 shillings, and 9 pence on her house rent, clothing and wood allowances, and medical bills. To cover these costs, in May the town asked the Connecticut General Assembly to allow the Guilford selectmen to sell the two acres of land she owned on Thirty Mile Island near Haddam to cover the “large sum” they had expended on Ann’s needs.

Ann Tantapan, who was born Ann Cyrus, married a Niantic sailor, James Tantapan (alternately spelled Tantipinant, Tantipine, and Tantipen). In 1790 Ann’s sister-in-law Sarah Wright Cyrus, the widow of Ann’s brother Daniel, petitioned the Connecticut General Assembly. Sarah identified herself as an Englishwoman in her petition, but Vicki Welch, whose book And They Were Related, Too: A Study of Eleven Generations of One American Family! (Xlibris, 2006) covers the extensive and complex genealogies of the Wrights, says Sarah was probably Native. Sarah had lost both of her sons, enlistees in Selden’s Regiment of the Connecticut Line, during the American Revolution. Asa and William Cyrus both died on December 20, 1776 after five months and 25 days of service.

Sarah’s children had been apprenticed and trained in trades, according to her petition, but the war had taken them, and she was left only with land on Thirty Mile Island that had belonged to Daniel. “[T]he family of Daniel Cyrus and Cobcozen are all extinct and…there is no surviving heir of said land, except your petitioner,” she told the legislators. She wanted the assemblymen to take “her unhappy case into your wise consideration and empower Ezra Brainerd, Esq., of Haddam or some other meet person to sell said four acres of land.” And with that, the last legally recognized Indigenous claim to Thirty Mile Island came to an end.

One hundred years earlier colonial courts had been sites for Indigenous people to contest power. In May 1697 the Connecticut Colony’s records show it abandoned its policy of requiring colony approval for the sale of Indigenous lands to settlers and opened Middletown and the surrounding area to purchase by individuals. Middletown (which straddled the Connecticut River and included the present-day town of Portland) was still occupied by the Wangunk. Thirty Mile Island was clearly going to be ripe for purchase. Within days of the legislature’s announcement, the island’s sunksquaw came to court. She chose a novel means to preserve her land and her people.

“I, Pampenum, an Indian Squaw” the document in her hand declared to the Court, “…doe now make this my Last Will and Testament.” Her will divided her island among her friends and relations upon her demise. She left parcels to her cousin Nanico’s two children, her brother Wawquashat and his son, and others. Ensuring the descent of her land by English law to members of her clan was not her only purpose. The will declared that “[e]very of which parts or parcells of my said Island given to my said Relations and friends as above mentioned, …shall not bee by them, nor any of theirs Alienated or Sold to any person or p[e]rsons at any time hereafter, for ever.” With these words, Pampenum defiantly announced to the colonial authorities that her land would remain in Wangunk hands in perpetuity. Pampenum’s response to the colonial law regarding the sale of Indian property was to use other colonial law to circumvent it. Her strategy may have been the earliest attempt in Connecticut to use the colonial probate system to preserve Indian autonomy over that most precious possession, land, as the co-author of this article Katherine Hermes documents in “‘By their desire recorded’: Native American Wills and Estate Papers in Colonial Connecticut,” published in 1999 in Connecticut History Review. Native women, including some of the relatives of Sarah Onepenny, would continue to use wills to preserve lands well into the 19th century.

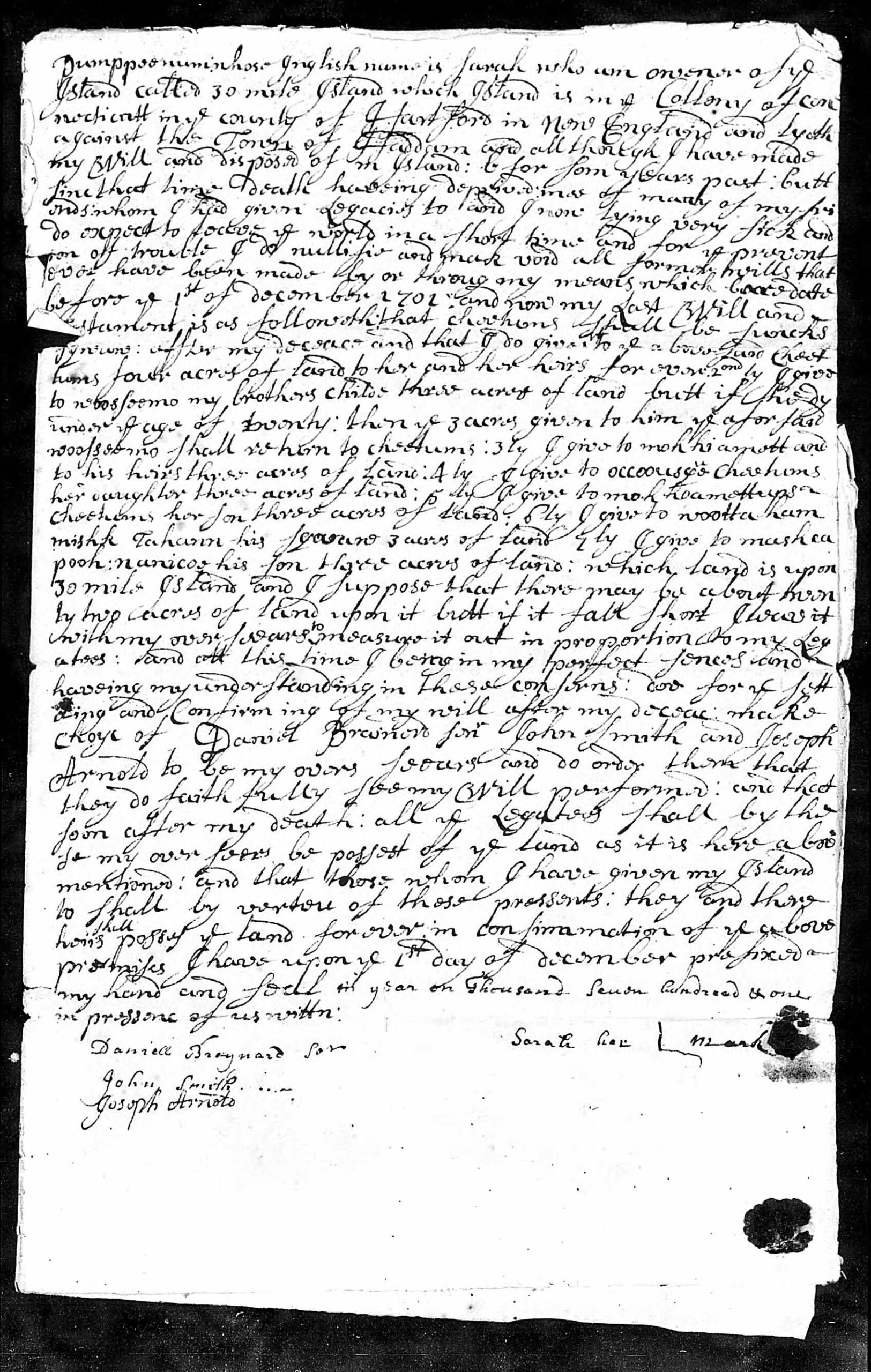

This female initiative to preserve land for their descendants stands in contrast to evidence, manifested in deeds, that the Wangunk sold land as part of a diplomatic strategy to appease colonists or to form alliances, and later simply to pay debts accumulated in a colonial system that kept Native people poor and in need. The most profound female initiative evidenced in the Connecticut probate documents is Pampenum’s effort to keep her land under Wangunk-Niantic ownership. In a second will made in 1701 Pampenum continued her attempt to keep her island among her own people: “they and there heirs shall possess ye land forever.”

Pampenum’s status in her community is established by her actions and her words regarding her estate, particularly with respect to this second will. When certain Native women appeared in court, they were recognized by colonial authorities as sunksquaws. Pampenum, in her second will written in response to her own grave illness, named her successor: “[C]heehums shall be Suncks Squaw after my deceace.” Cheehums was identified in the second will as the mother of Mohheamettup, later known as Mahomet Yeomanum. In anticipation of her imminent death Pampenum turned to English law to secure Indian succession to power. The probate court accepted the first will for reasons unspecified in the court order, rejecting the second. That rejection had serious legal consequences, because many of those named in the first will had died by the time Pampenum wrote the second will.

As Pampenum’s second will reveals, her brother Wawquashat died in Hartford sometime between the first and second wills, leaving a son, Ooseemoo (Seemook). By rejecting the second will, the court disinherited Ooseemoo. Mahomet Yeomanum died in London on August 8, 1736 from smallpox. He had gone to England to argue his side in a case disputing the succession of the Mohegan sachemship before King George II’s privy council. It is not clear what happened to Nanico’s children, but there was a grandson, Panhackshun, born between the first and second wills, who was also disinherited. By using the first will instead of the second the court constricted inheritance.

By 1764 Thirty Mile Island was the only land remaining under Wangunk authority. After Pampenum’s death in 1704 a man named Cobcozen appears in colonial documents as the sole heir to the island. Depositions indicate that he may have inherited through his wife, whose identity is unknown. Sometime before 1788 Cobcozen’s son and grandchildren left Thirty Mile Island for Guilford. Native men needed trades to earn money, and those could only be had in settler towns, especially those near New London or New Haven. The need for ready cash often meant renting lands and houses rather than owning one’s own. That practice often resulted in men’s accumulation of debt, which could be particularly hard for their widows and orphans to repay.

As the Tantapan and Cyrus families abandoned Thirty Mile Island for settler towns, the care of older widows fell to those towns. When Ann Tantapan and Sarah Cyrus came to the end of their lives the towns of Guilford and Lyme were emboldened to declare them the last heirs of Thirty Mile Island, even though Ann Tantapan had surviving family members. The problem was not that no one could have inherited the island. The problem was that Connecticut’s system made it nearly impossible for Native people to hold onto land. Courts were all too quick to pronounce individual Native people as the “last Indian,” as historian Jean O’Brien warns us in her book Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England (The University of Minnesota Press, 2010). Pampenum and other Wangunk women went into the colonial courts to use the law for their own purposes. Perhaps fearing this bold strategy, the courts found a way to use the law to undermine Native self-determination.

The use of the term “Wangunk” to describe the Indigenous community faded by the 1790s with the diaspora of its former inhabitants. By 1774 there were approximately 600 adult “Indians” identified by a Connecticut Colony census, although the actual number was no doubt much greater. The story, though, is far from one of passive decline. Pampenum and her circle of women, determined to keep land among their descendants through the use of the colonists’ own probate court system, ultimately failed, but from the 1690s to the 1790s, her will prevailed.

Katherine Hermes is the publisher of Connecticut Explored and professor of history, emerita, at Central Connecticut State University. Alexandra Maravel is adjunct professor of history at CCSU. Hermes last wrote “Unburying Hartford’s Native and African History,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2019. Hermes and Maravel co-authored the article “Finding the Onepennys among the Wongunk,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut 79: 95 (2017), and worked together on the digital project “Uncovering Their History: African, African-American and Native-American Burials in Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground, 1640-1815,” africannativeburialsct.org/, for the Ancient Burying Ground Association.

Christine Woodside, “A Tale of Shad, the State Fish,” connecticuthistory.org/a-tale-of-shad-the-state-fish/Haddam Island State Park

Christine Woodside, “A Tale of Shad, the State Fish,” connecticuthistory.org/a-tale-of-shad-the-state-fish/Haddam Island State Park

In 1944 the state of Connecticut created Haddam Island State Park as a “scenic reserve state park.” The Connecticut Tourism Office website recommends visiting the island for birdwatching, boating, and fishing. It is accessible only by boat. explorect.org/haddam-island/