(c) Connecticut Explored, Winter 2014-2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1917 the United States Government embarked upon an unprecedented experiment—the planning and construction of neighborhoods and housing for American workers and their families. Within a period of two years over 83 new housing projects in 26 States were designed, planned and had commenced construction. The achievements of this effort are staggering.

—Professor Eran Ben-Joseph, MIT School of Architecture + Planning (http://web.mit.edu/ebj/www/ww1/ww1a.html)

During World War I, Bridgeport’s Remington Arms munitions plant produced 50 percent of the U.S. Army’s small-arms cartridges. At the time, Remington employed 17,000 laborers in a factory complex covering 73 acres on the city’s northeastern side. Housing those workers was a challenge. Bridgeport had a severe shortage of housing, as city planner John Nolan noted in a 1916 report commissioned by civic leaders simply titled “More Houses for Bridgeport.” The private market proved unable to meet housing needs.

Connecticut has a tradition dating to the 18th century of mill owners pr oviding workers housing in “mill towns.” As detailed in Wartime Emergency Housing in Bridgeport, 1916-1920, a 1990 nomination to the National Register of Historic Places by historians Steven Bedford and Nora Lucas, the Remington Arms Corporation attempted to fill the housing need by constructing more than 500 homes in neighborhoods they called Remington City, Remington Village, Remington Cottages, and Remington Apartments. When the company ceased construction in late 1916, the shortage remained. In two concurrent efforts, local Bridgeport Housing Company (BHC) and the federal government’s United States Housing Corporation (USHC) raced to purchase land, hire architects, secure building materials that were in short supply, and complete dwellings between 1916 and 1920.

oviding workers housing in “mill towns.” As detailed in Wartime Emergency Housing in Bridgeport, 1916-1920, a 1990 nomination to the National Register of Historic Places by historians Steven Bedford and Nora Lucas, the Remington Arms Corporation attempted to fill the housing need by constructing more than 500 homes in neighborhoods they called Remington City, Remington Village, Remington Cottages, and Remington Apartments. When the company ceased construction in late 1916, the shortage remained. In two concurrent efforts, local Bridgeport Housing Company (BHC) and the federal government’s United States Housing Corporation (USHC) raced to purchase land, hire architects, secure building materials that were in short supply, and complete dwellings between 1916 and 1920.

Business and community leaders worried that the shortage of housing was creating a surge in labor turnover leading to inefficiency. In August 1916, the Bridgeport Chamber of Commerce incorporated itself as the Bridgeport Housing Company with $1 million in capital to construct 1,000 homes. The resulting Park Apartments and Gateway Village were built within the city limits of Bridgeport, and two additional developments, Grassmere Village and Lordship Village, were completed outside the city limits in the neighboring town of Fairfield.

As Bedford and Lucas note, “In the 20 months following the [U.S.] declaration of war [in April 1917], Bridgeport’s population exploded from 100,000 to 150,000 as workers flooded the city seeking employment in arms-related industries. The sudden influx overwhelmed the city.…” Cities across the country were experiencing the same thing. It became clear that the federal government would need to step in. Congress authorized and funded the United States Housing Corporation and the President authorized its incorporation in New York on July 9, 1918 with $100 million. Of the 83 developments planned across the nation, 12 were in Connecticut cities: Bridgeport, New London, and Waterbury.

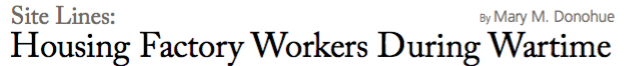

The USHC attracted extremely bright architects, city planners, and engineers anxious to use modern British and German worker’s villages as models. They also employed English Garden City planning practices to build good-looking, carefully designed housing sited in picturesque settings with curving streets, public open spaces, and varying streetscapes. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. (whose father co-designed New York City’s Central Park) was the director of the USHC’s town planning division. The division developed architectural designs that connected with local building practices and employed local architects. It strove to design houses with the wife in mind, for families without servants, and to build for comfort, convenience, and labor saving. Although standardized architectural plans with standardized designs for building features such as windows, doors, stairs, and lighting fixtures were developed, they were combined in ways that combated the monotony found in low-cost workers housing of the period, particularly New England’s three-deckers.

The USHC attracted extremely bright architects, city planners, and engineers anxious to use modern British and German worker’s villages as models. They also employed English Garden City planning practices to build good-looking, carefully designed housing sited in picturesque settings with curving streets, public open spaces, and varying streetscapes. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. (whose father co-designed New York City’s Central Park) was the director of the USHC’s town planning division. The division developed architectural designs that connected with local building practices and employed local architects. It strove to design houses with the wife in mind, for families without servants, and to build for comfort, convenience, and labor saving. Although standardized architectural plans with standardized designs for building features such as windows, doors, stairs, and lighting fixtures were developed, they were combined in ways that combated the monotony found in low-cost workers housing of the period, particularly New England’s three-deckers.

Seaside Village, originally known as the Crane Development (1918), in Bridgeport was described in the USHC Report of 1919 as “having land as flat as a piece of paper.” Despite that, the designers used curving streets, clustered building masses, and tree placement to achieve what the report terms “an artistically dangerous and difficult thing…done with notable artistic success.” The planned area encompassed nearly 25 acres and housed 257 families in a variety of semi-detached and row houses. Other Bridgeport projects included Black Rock Gardens, Lakeview Village (originally known as Mill Green), and Wilmot Apartments.

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, the USHC cancelled projects and sold off completed projects to private homeowners or tenant associations. In “Lessons from Housing Developments of the United States Housing Corporation,” (Monthly Labor Review, May 1919), Olmsted wrote, “They are intelligent, even if hurried, experiments on a large scale, directed toward securing the best obtainable results in the way of comfortable, healthful, pleasant living conditions for persons of limited means.” Today, the quality of the developments still stands out.

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, the USHC cancelled projects and sold off completed projects to private homeowners or tenant associations. In “Lessons from Housing Developments of the United States Housing Corporation,” (Monthly Labor Review, May 1919), Olmsted wrote, “They are intelligent, even if hurried, experiments on a large scale, directed toward securing the best obtainable results in the way of comfortable, healthful, pleasant living conditions for persons of limited means.” Today, the quality of the developments still stands out.

Mary M. Donohue is an award-winning author and architectural historian. She serves as assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut

Explore!

National Register of Historic Places Nominations

Every nomination to the National Register of Historic Places contains original research by qualified historians and often presents surprising new information. The National Register is the nation’s honor roll of properties that deserve to be preserved. Properties more than 50 years old may be nominated; historic preservationists often are in the vanguard of scholarly work on properties of more recent vintage or vernacular buildings. Nominations are presented to an interdisciplinary review board before they are sent to Washington. Once at the National Register offices, they are further examined before the property is officially listed. Connecticut’s nominations, more than 45 years’ worth of first-rate documentation of the state’s built environment, are available digitally on the official National Register Web site, nps.gov/nr.