Theodate Pope, 1915. Hill-Stead Museum. Inset: “It is precisely the kind of house one would naturally look for in Farmington,” Notable American Homes, “American Homes and Gardens,” February 1910

A Curator-to-Curator Conversation

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2002

Subscribe/Purchases Back Issues!

Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington is celebrating the house’s 100th anniversary. Anniversaries are always a good time for reflection, and so Hill-Stead’s curator, Cindy Cormier, invited Tom Denenberg to talk with her about Hill-Stead and the cultural moment that produced it. Denenberg is the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s Richard Koopman Curator of American Decorative Arts and is currently organizing and exhibition about Wallace Nutting and the Colonial Revival to open at the Atheneum in June 2003. His book, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America, will be published by Yale University Press this winter.

Architect Theodate Pope Riddle (then Theodate Pope) designed and built Hill-Stead in 1901 for her parents. It was her first major architectural work and was designed around her father’s collection of French Impressionist paintings. Riddle had fallen in love with Farmington as a Miss Porter’s School student and had moved there in 1890, initially purchasing and renovating an 18th-century farmhouse. As a means of enticing her parents to move to Farmington from their Victorian Richardsonian Romanesque style mansion (with its solid masonry construction, rounded arches, towers and asymmetry) down the street from the Rockefellers on Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, she proposed a Colonial-style country house—but on the grand scale to which her parents were accustomed.

Riddle became a licensed architect in New York in 1916 and was one of the first women to do so in Connecticut in 1933 when the state instituted the licensing of architects. She designed several schools, (including Westover School in Middlebury, Connecticut, and Avon Old Farms School in Avon, Connecticut), several private homes, and the reconstruction of the birthplace of Theodore Roosevelt in New York City. In 1916, at the age of 49, she married John Wallace Riddle, a 52-year-old diplomat who had served in Russia. They took up residence at Hill-Stead. Upon her death in 1946, as stipulated by her will, Hill-Stead became a museum open to the public.

Cindy: I tell visitors to Hill-Stead that the Popes had a number of architectural styles at their disposal. They could have created a Renaissance Revival mansion, modeled after the European villas they had seen in their travels, or they could have fashioned an English Tudor home, in deference to their affection for all things British, but they chose the Colonial Revival for their country house. It is hard to imagine any other style here in Farmington with its Colonial era and Revolutionary War history. If the Popes wanted to fit into the Town of Farmington, with its fabulous architectural history on Main Street, they couldn’t have made any other choice really. This was the choice to be made in this village at this time. How do you present this to the visitor, when it seems so natural?

Tom: It seems a natural choice, but it’s also very self-conscious. If you were well-off at the turn of the century and had roots here in New England or were “from away” but understood Farmington as one of those distinctly “American” spots, then the Colonial Revival style was certainly the idiom in which to build and Farmington the place to do so. The influence of place at the turn of the 20th century, even going back to the Civil War, is crucial to understanding why Hill-Stead looks like a colonial mansion house and not a Renaissance Revival villa or a pseudo-Tudor manor. Those are all appropriate styles with appropriate ideologies for other communities. Compare, for example, Gilded Age Newport, Rhode Island, with Farmington. The ornate Renaissance Revival aesthetic so popular there would have been anathema here.

The common thread that runs through these two very different communities and styles, however, is the notion of “inverted tradition.” This is not to say folks were completely making up stories and styles, but that they were selective when they created narratives with the built environment. It’s very much the same today. In the end, it becomes a question of how people negotiate change and make themselves comfortable in the modern world. Places and environments are therapeutic. Farmington offered Theodate and others a Yankee sense of place, very different from the big cities where so many led their economic lives. The first generation off the farm, so to speak, often went West to make their money, but then their kids came back to places like Farmington to build their country houses.

Cindy: That’s certainly what the Popes did. They left their family homes in Vermont and Maine for Ohio, made their fortune, built an urban castle, and then returned to their Yankee heritage by creating this country estate in Farmington, Connecticut.

Tom: The next generations’ need for a Yankee heritage is so telling. It was their parents who turned the country into an industrial, heterogenous nation. The children required these myths of old-time New England and old America to restore a cohesive sense of community and nation.

Cindy: So the Colonial Revival is in some way an attempt to reunite and build one nation again?

Tom: Yes, I think the Colonial Revival has a profound unifying mission. Scholars traditionally dated the beginning of the Colonial Revival to about 1876, when attention was focused on the centennial of the nation’s birth; they equated the Revival’s decline with the rise of European modernism in this country. I have a different, somewhat heretical view on the Colonial Revival. I believe the need for a useful past has always been there, starting with the first English settlers to hop off the boat.

This need plays out time and time again in our history. In the 1830s and 1840s, people were concerned with the passing of the Revolutionary War generation. So the old-timers began to record their stories as “hero tales” for the young nation. Sounds rather like our current focus on the World War II generation, doesn’t it? Twenty years later, in the 1860s and 1870s, writers such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and John Greenleaf Whittier published odes to the glorious past venerating such characters as Miles Standish and Priscilla Mullins (a young woman whose family came over on the Mayflower to settle in Massachusetts.)

In fact, Priscilla imagery became quite popular in the late 19th century. She shows up in poems, paintings, John Roger’s parlor statue groups [See “John Rogers Jr., the People’s Sculptor,” Winter 2019-2020), and schoolhouse tales. It’s interesting that she became a domestic icon at a time when middle and upper-class women were increasing their calls for a broader role in the public sphere. But what sort of role model was provided by the Priscilla mythology? The message was: “good” women stay home, mind the kids, and spin cloth for the family, even at a time when the mills of Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts were moving textile production out of the middle-class home. Priscilla is the conservative sister, the counterpart to the idea of the “new woman” that emerges in the 1890s. The new woman wants a career. She plays tennis, rides a bicycle, and wants to vote—very different from Priscilla.

Theodate Pope seated before her hearth in her 18th-century farmhouse on High Street, Farmington, 1902. photo: Gertrude Kasebier, Hill-Stead Museum Archives

Cindy: Theodate Pope was a combination of Priscilla and the new woman. In 1905, she joined the Colonial Dames, a society whose purpose was to create a popular interest in our Colonial history, to stimulate a genuine love of our country, and to impress upon the young the sacred obligation of honoring the memory of our heroic ancestors. It’s all about the forefathers. In the meantime, Theodate is also running a business, becoming an architect, living alone and unmarried, and influencing women’s causes, both charitable and intellectual.

Tom: She was the new woman but she still needed the sense of place and the sense of community provided by Hill-Stead and the broader Colonial Revival. Think of it this way, who is Martha Stewart’s audience?

Cindy: They’re working-women, who are trying to do it all. To be progressive out in the world without abandoning the traditional at home. To decorate the house and create a moral environment for their families.

Tom: If you look at the 1870s and 1880s, there’s an absolute fetish for the image of the New England village and small-town life. By the 1890s and early 20th century, whole towns such as Litchfield had recreated themselves in this Colonial manner.

Cindy: Farmington was doing that as well in the 1890s with its Village Improvement Society, established by important women of the town, including many at Miss Porter’s School. They wished to give Main Street more distinction by painting the houses uniformly white, adding date markers to provide a sense of history, and landscaping for greater natural beauty.

Tom: I think the generational story is very important to the Colonial Revival. It seems to be a truism that you always “spit in the eye of your parents” and go looking for the “good old days” of your grandparents. The Colonial Revival can be interpreted as a reaction to the world created by the revivalists’ parents: dark, satanic mills ostentatious Renaissance Revival mansions, all of which resulted from (and led to) immigration, urbanization, industrialization, and the extreme heterogeneous nature of late 19th-century society. The ideal of the quaint rural New England village had been shattered.

The Colonial Revivalists’ interpretation and “rebuilding” of the 17th- or 18th-century ideal was, in truth, also an evocation of their grandparents’ era, the early 19th century. During this period, the age of the New Republic, towns were becoming more prosperous and there was a resulting “clean up” of the landscape. The Colonial Revival’s enactment of the picturesque New England town, white-washed and with white picket fences, has much more to do with romantic notions of the New Republic than the true Colonial period. The Revivalists in the late 19th century who looked to the past for a halcyon Colonial period really located it in their grandparents’ generation—some 50 years after the Colonial era had come to a close.

Cindy: All these comments are made concrete in the life of Theodate Pope. In her diaries, writing as a young woman, she agonizes over how she can make her life meaningful and what she can contribute. I never thought of it as a reaction to her father’s industrial accomplishments and quick materialistic gains. She yearns for a return to Intellectualism but also wants to move onto a utopian farm, milk her own cows, and raise her own produce—which she did in fact do from 1890 to her death in 1946.

Tom: We haven’t even talked of authenticity, a key word in all of this.

Cindy: Authenticity for Theodate Pope was taking her first home in Farmington, an 18th-century farmhouse, restoring it and decorating it in an “authentic” Colonial manner.

Tom: But authenticity does not equal accuracy. In different time periods within the Colonial Revival, accuracy and authenticity are almost in conflict.

Cindy: Hill-Stead really was her parents’ house, and her father would not have wanted to live in a home where every bedroom did not have a bathroom and central heat and cooling. Authenticity was not allowed to compromise comfort.

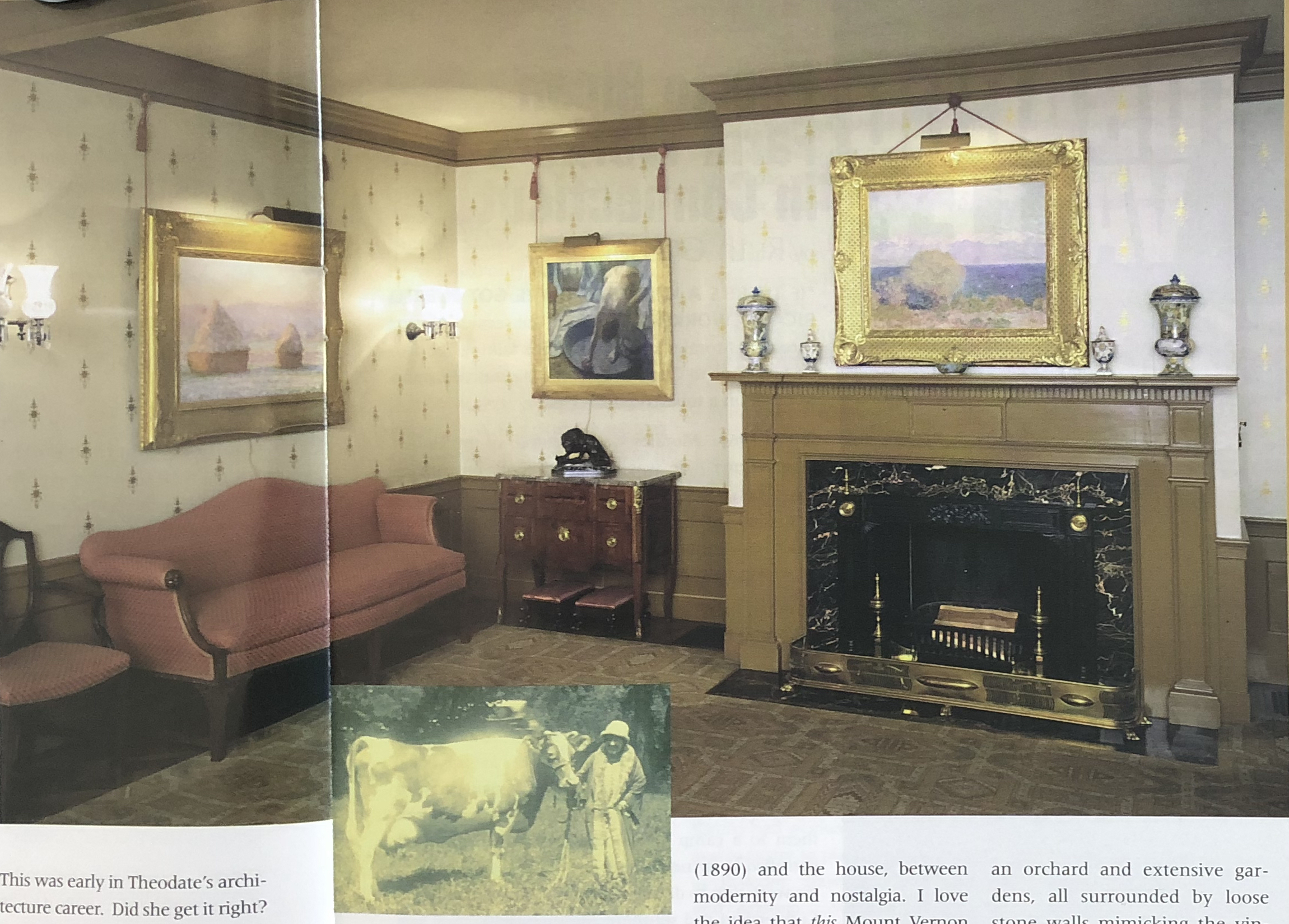

Drawing room, Hill-Stead Museum, 2001. Inset: Theodate Pope Riddle with her prize-winning Guernsey cow, Anesthesia’s Faith, 1925. Hill-Stead Museum Archives

Tom: Authenticity and accuracy ebb and flow throughout the Colonial Revival. In the 1870s and 1880s, odd hybrid objects, such as spinning wheel chairs, were considered legitimate additions to the modern “Colonial” home. People would send Grandma’s spinning wheel to a Boston company that reconfigured its parts into a conversation piece. Grandma would not have recognized it, but it was an “authentic” touchstone of Grandma’s Yankee virtues in the middle parlor. By the early 20th century, however, there is a search for accuracy, led by architects like Norman Isham or J. Frederick Kelly in Connecticut, and eventually Wallace Nutting in the decorative arts in furniture.

Cindy: Was this a quest for accuracy an attempt to maintain the validity or importance of the Colonial Revival aesthetic as Modernism came to the fore?

Tom: I think it does have a lot to do with the rise of Modernism after World War II. By 1950, there was almost a form of cultural amnesia in this country. People could not imagine anyone ever wanting anything as odd as a spinning wheel chair. Wallace Nutting’s fortunes bear this out. He sold millions of photographs with Colonial themes between 1906 and 1941. Yet by the 1950s, you would have been hard-pressed to find anyone who would admit to owning one. It isn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that evocations of the Colonial era are once more in vogue. The rise of European Modernism shoved the Colonial Revival in the closet or, rather, the attic.

Cindy: When Theodate was living in her 18th-century farmhouse on High Street, would she have been aware of the Colonial Revival as an organized movement? Or was the Colonial Revival given its name at a later time?

Tom: Most movements are labeled by historians after the fact. However, there were groups, such as the Colonial Dames, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Walpole Society, and decorative arts guilds (such as those formed for rug hooking) that quite consciously preserved and retold America’s Colonial Past.

A few years ago, there was a “fad” for performance theory and performance studies among historians. The premise is that we are all “performing” our identities on a daily basis. Building a colonial mansion, rocking in a spinning wheel chair, or gathering half a dozen women in a room to hook rugs in the 1890s, for example, is some serious performance!

Cindy: Is Hill-Stead a good example of the Colonial Revival? This was early in Theodate’s architecture career. Did she get it right?

Tom: It is absolutely the formula of the Colonial Revival. No one was aiming for accuracy here, but the estate contains layers of historical meaning. The place, the garden, the references to a genteel past at Mount Vernon—these all come together to create an icon. Theodate wanted an authentic experience and to shelter herself, her family, and friends from the vicissitudes of modern life.

Cindy: Did she create something new or did she merely mimic the past?

Tom: Well, George Washingon didn’t collect French Impressionist paintings! Seriously, I think there is a complete unity of thought between Monet’s “Haystacks” (1890) and the house, between modernity and nostalgia. I love the idea that this Mount Vernon was built around those Monets. The restraint here is remarkable and again very sympathetic to the notion of a Yankee town.

Cindy: Hill-Stead provided almost an immersion experience. The Popes could leave the urban center of industry and come to the country, like George Washington, to be the gentleman farmer. Here, they raised Guernsey cows and maintained an orchard and extensive gardens, all surrounded by loose stone walls mimicking the vintage stone walls to be found throughout the area.

Tom: You can argue over what’s accurate, what’s authentic, and the distinction between the two, but the quest here was for a seamless experience. From stonewall to house to paintings to town, there’s a coherent narrative. That is the art of Hill-Stead.

Explore!

Hill-Stead Museum

Mountain Road, Farmington

Hillstead.org

“The Modernism of Hill-Stead’s Theodate Pope,”Winter 2009/2010

“Site Lines: Golf At Hill-Stead,” Summer 2018

“Alfred Pope and Lunch with Monet” Winter 2004/2005

Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art will present the exhibition Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America, curated by Tom Denenberg, from June 5 through October 19, 2003. This exhibition, accompanied by a richly illustrated book, a lecture series, and symposium, will be the first large-scale exploration of the life and work of Wallace Nutting (1861-1941).

A Congregational minister turned historical entrepreneur, Nutting is best known as a collector and antiquarian. He was also a photographer, writer, and owner of a reproduction furniture company and chain of museum houses in three New England states. Well known in his day, Nutting served as the de facto spokesman for the Colonial Revival in the early 20th century.