By Beth Burgess

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Marital betrayal. Incest. An illegitimate child. Wait—Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote about those topics?

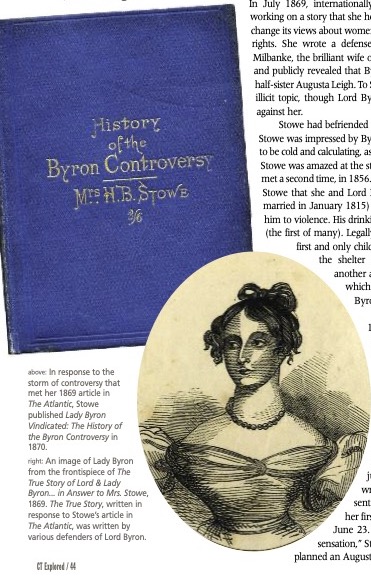

top left: Stowe’s “Lady Byron Vindicated: The History of the Byron Controversy,” 1870. below: An image of Lady Byron from the frontispiece of “The True Story of Lord & Lady Byron… in Answer to Mrs. Stowe,” written in response to Stowe’s article in The Atlantic, written by various defenders of Lord Byron, 1869. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

In July 1869, internationally famous author Harriet Beecher Stowe began working on a story that she hoped would make the world stop, read, think, and change its views about women’s rights, specifically married women’s lack of civil rights. She wrote a defense of her deceased friend Lady Byron, or Anne Milbanke, the brilliant wife of the late British poet (and celebrity) Lord Byron, and publicly revealed that Byron had had an incestuous relationship with his half-sister Augusta Leigh. To Stowe’s surprise, the public proved unready for this illicit topic, though Lord Byron had died some 45 years earlier, and turned against her

Stowe had befriended Lady Byron on her first visit to England, in 1853. Stowe was impressed by Byron’s warmth and intelligence. She found her not to be cold and calculating, as Lord Byron’s poetry and general society suggested. Stowe was amazed at the story Lady Byron told her in confidence when they met a second time in 1856. Byron, knowing she had little time left to live, told Stowe that she and Lord Byron had been ill matched from the start (they married in January 1815) and that Lord Byron’s financial debts soon drove him to violence. His drinking escalated, and he began an extra-marital affair (the first of many). Legally unable to divorce, in January 1816, when their first and only child, a daughter, was five weeks old, she left him for the shelter of her father’s home. Lord Byron carried on another affair, this time with his half-sister Augusta Leigh, which resulted in an illegitimate daughter. Lord and Lady Byron remained estranged until he died in 1824.

Stowe was moved to write her article after the 1868 publication in Paris of a memoir by Lord Byron’s former mistress, Countess Teresa Guiccioli of Italy. Her account, published in New York and London the following year as My Recollections of Lord Byron and Those of Eye-Witnesses of His Life (Harper & Brothers, 1869), was a gushing paean to Lord Byron. As Stowe biographer Joan Hedrick notes in Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Life (Oxford University Press, 1994), Stowe felt compelled to defend her now deceased friend. “I tremble at what I am doing & saying but I feel that justice demands it of me & I must not fail,” Stowe wrote to William Dean Howells in July 1869. Stowe sent The Atlantic magazine interim editor James Parton her first draft of “The True Story of Lady Byron’s Life” on June 23. Knowing it “will probably make a good deal of sensation,” Stowe asked for time to review the proof sheets and planned an August publication.

But Stowe’s motives were not solely born of concern for Lady Byron’s legacy. She hoped that her story, which ultimately appeared on September 1, 1869, “…would be the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of woman’s sexual slavery,” Hedrick writes. Stowe’s story touched on the negative aspects of marriage, those used by suffragists to forward their cause, such as domestic abuse, and lack of civil rights. Scholars speculate Stowe had another motive for writing the story: to regain a modern audience bored with her folksy stories—as evidenced by a bad review of her latest work Oldtown Folks (1869).

Weeks before the magazine story went to press, Stowe suffered a “sinking turn,” or, in today’s terms, a physical collapse. The pressure of knowing her reputation and career—and potentially those of her family—were on the line for “speaking the unspeakable” was too much to bear. She went to the Berkshires to recuperate.

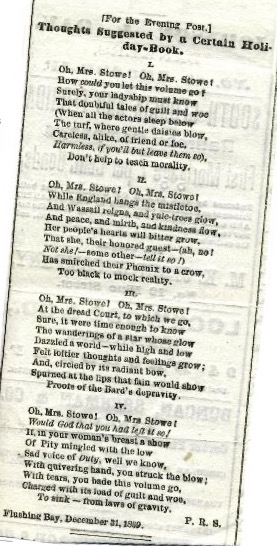

A poem lamenting Stowe’s taking up the Byron scandal appeared in an unknown publication, December 1869. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

The outpouring of anger and disbelief following the article’s publication was immense. The Independent called her story “startling in accusation, barren in proof, inaccurate in dates, infelicitous in style.” “As to Mrs. Stowe,” the British Blackwood’s Magazine noted, “all who would guard the purity of the home from pollution, and the sanctity of the grave from outrage—have joined in one unanimous chorus of condemnation.” “Stowe was accused of sensationalism…,” Hedrick notes, “and told that even if the story were true, she ‘should not have stained herself’ by revealing it.” She was accused of having no proof. The British press soon swarmed with other accounts (along with negative commentary), and these added to the confusion.

The story damaged The Atlantic, too. Though the issue sold out, magazine subscriptions waned in the months following its publication. According to Mark Antony De Wolfe Howe in The Atlantic Monthly and Its Makers (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1919), the magazine’s editors agreed Stowe’s salacious story had alienated thousands of their subscribers.

Rather than retreat, Stowe responded by expanding her article into book form, much as she had countered criticism of Uncle Tom’s Cabin with A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853). Lady Byron Vindicated, published by Fields, Osgood & Co. (and Sampson Low in Britain) was published the following year. But the result was a cumbersome text in which Stowe’s writing couldn’t paint clear pictures and capture public sentiment the way Uncle Tom’s Cabin had. She again retreated from the public spotlight. In the case of Lady Byron’s story, it was Stowe’s written word against the world, and the world won.

Beth Burgess is collections manager at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

Explore!

Read more stories about Harriet Beecher Stowe:

“The Most Famous American,” Summer 2011

“The Beechers Take the Water Cure,” Feb/Mar/Apr 2004

Return to the Fall 2014: Power of the Pen issue

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!