Elizabeth Park rose garden. photo: Lea Anne Moran. See her story “Connecticut’s Historic Rose Gardens,” Winter 2017-2018

By Mary Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc.

Listen to the episode!

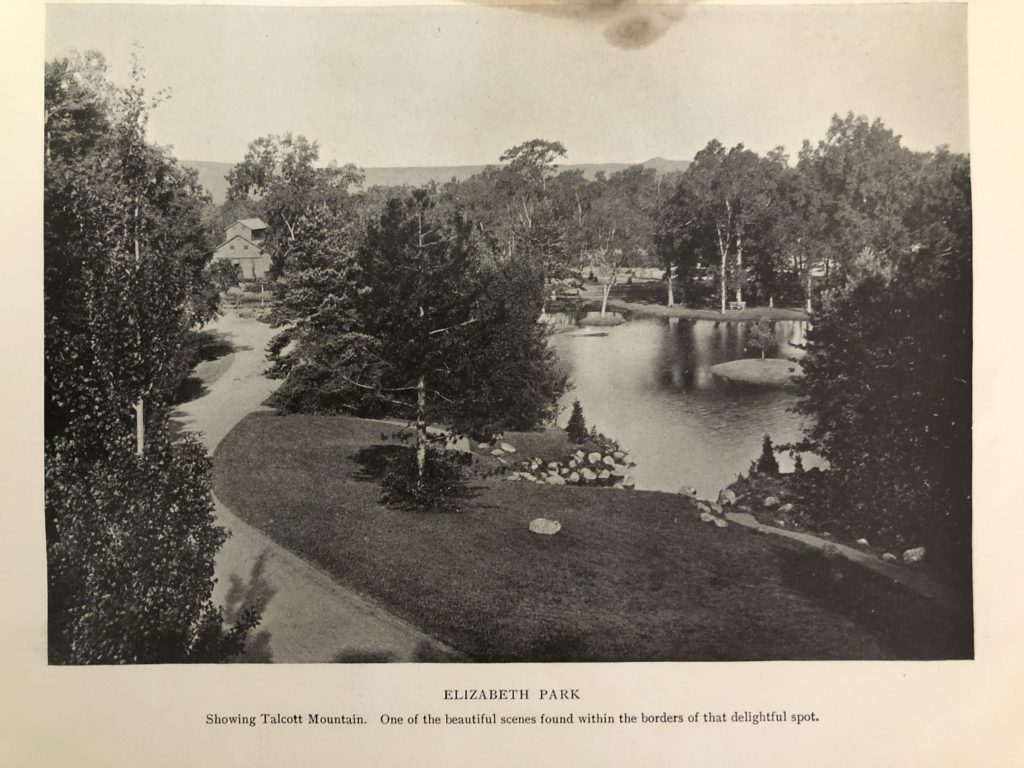

Visitors have been enchanted by the thousands of soft and fragrant rose petals in Elizabeth Park’s rose garden since it opened in 1904. Climbing roses intertwined in overhead garlands; hybrid tea roses and heritage roses in every color symbolize romance, friendship, and passion. Elizabeth Park is home to the country’s oldest public rose garden. Visitors by the thousands come to stroll in the rose garden and sit in the vine-covered gazebo. Generations of prom goers as well as wedding parties have had their photos taken there.

But how did Elizabeth Park become the public park it is today? Let’s start the story with Hartford’s first public park, Bushnell Park. Hartford’s first park, Bushnell Park in the heart of downtown Hartford adjacent to the Connecticut State Capitol, was named for Rev. Horace Bushnell, its main promoter. Bushnell believed that “one must go to nature to understand God,” and he persuaded enough people that the city needed a spacious public ornamental ground to make the park a reality.

Hartford citizens voted in 1854 to accept the plan for Bushnell Park, making it the first municipal park in the United States to be conceived of, built, and paid for by a city through popular vote.

Hartford proceeded to build an enviable park system that benefited from the generous nature of some of its wealthiest residents. Between 1894 and 1900 a profuse addition of parkland, known as the “Rain of Parks,” occurred. This outpouring of civic pride and philanthropy added 1,000 acres of parkland, including Elizabeth, Pope, Keney (for which the land was donated), Goodwin, and Riverside (for which the land was purchased) parks. In 1905 Elizabeth Jarvis Colt left the Colt estate to the city for use as a city park. Each section of the city was served by a large municipal park. These parks ringed the city and often spilled over the city line into adjoining towns in open areas not yet suburbanized.

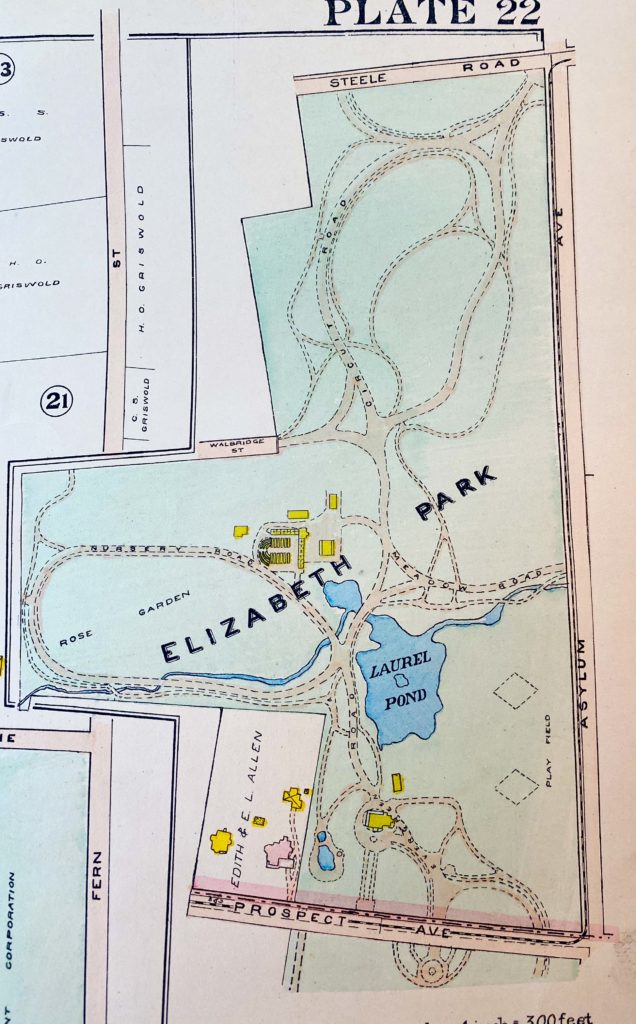

In 1839 wealthy Hartford businessman Charles Floyer Pond (1809 – 1869) purchased 33 acres of land on Hartford’s western edge, adding 16 acres in 1857 for a total of 66 acres. A graduate of Yale Law School, he served as president of the Hartford and New Haven Railroad Company. His estate was divided by Prospect Avenue; the eastern part was in Hartford and the western part in the neighboring town of West Hartford. The estate was known as Prospect Hill Farm. By 1859 C.F. Pond raised thoroughbred Ayrshire cattle, a prized livestock. His estate might be called a “gentleman’s farm” or a “hobby farm,” owned as it was by a wealthy businessman and including a working farm.

C.F. Pond died in 1869. His oldest son Charles Murray Pond (1837 – 1894) inherited the estate. The following year, Charles M. Pond married Sarah Elizabeth Aldrich (1840 – 1891). Successful in his own right, Pond served as the treasurer of the Hartford and New Haven Railroad line until 1873 when the railroad was consolidated. A lifelong Democrat, he was elected to the Connecticut House of Representatives in 1863 and 1868, served five terms in the State Senate between 1872 and 1877, and was State Treasurer in 1870. Well-known in Hartford business circles, he attended Trinity College and was an organizer of the Hartford Trust Company, serving as president from 1868 to 1879.

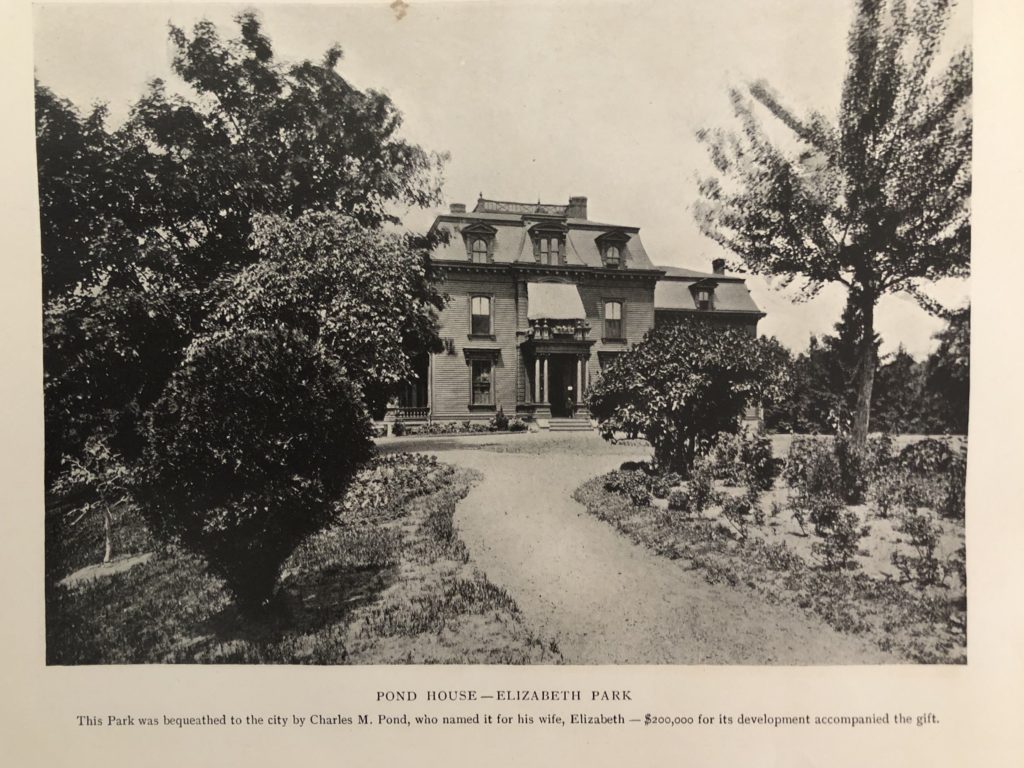

Charles & Elizabeth Pond house, Prospect Avenue, Hartford, c. 1920s. It was demolished in the 1950s. from “Souvenir Views of Hartford, Conn,” unknown date.

After their marriage in 1870, the Ponds built a grand mansion on Prospect Avenue. The massive French Second Empire-style home sported a mansard roof characteristic of the style.

The Origins of Elizabeth Park

In 1870 Pond asked Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture and co-designer of Central Park in New York City, to assess the possibility of turning land on the city’s west side, including Pond’s own estate, into a public park. Olmstead responded enthusiastically. Here’s what Olmsted wrote in a report to Pond in 1871:

The advantages of Prospect Hill as an eminence, however, greatly surpass those offered at any other point which can be reached quickly and agreeably from all parts of the city. Whenever this hill is cut up by roads, the superb views which are now enjoyed from it will be lost to the public. If ground sufficient to afford a look out at the top and to secure the control of the finest views should be taken, and this together with a portion of the meadow below it on the South East and the beautiful wood lands about it, would combine to offer all that is required to complete a very fine park system. “

Pond and his wife Elizabeth also loved gardens and trees and had formal gardens surrounding their home. The estate’s landscaping is attributed to Thomas Brown McClunie (1816-1903), perhaps Hartford’s first residential landscape gardener or landscape architect. Born in Scotland, McClunie studied at Edinburgh University. After stints designing gardens in Scotland and then estates along the Hudson River in the United States, he eventually came to Hartford. McClunie submitted a design in the competition for Bushnell Park. Although he did not win, his designs were used for the landscaping of the Connecticut State Capitol and the Connecticut State Hospital in Middletown. McClunie advertised as late as 1889 that he provided “plans and specifications for parks, cemeteries, and private residences.”

Charles M. Pond added land to his estate three times, eventually enlarging it to 90 acres. He continued his father’s interest in farming, switching from cattle to horses, poultry and tobacco. Pond bred famous trotters (horses). On Sunday afternoons, he hosted horse races around a dirt track near today’s Rose Garden.

In 1893 Rev. Francis Goodwin (1839-1923), a member of the city’s Board of Park Commissioners, worked with Pond to leave his estate to the city as a park. Goodwin’s slogan was “More Parks for Hartford.” Pond died in 1894, leaving his real estate plus $100,000 for the park with the provision that it be named after his beloved wife Elizabeth. Pond’s generosity also included giving the contents of his library to the YMCA including over 1,000 books, engravings, clocks and 100 stuffed birds.

But the estate was not settled quickly or quietly. Charles Pond’s brother Anson contested the will and testified in court that, “My brother was under the influence of liquor and morphine. He used both to excess and was often drunk, stupid, and unsteady. He believed he could speak to the dead and had mediums, seances and Ouija boards.” The City of Hartford ended up settling with Anson Pond for $87,500 — worth about $2.7 million dollars now.

The Hartford Board of Park Commissioners opened Elizabeth Park on July 8, 1897. A year earlier, the board hired Theodore Wirth (1863 – 1949) as the first professional superintendent for city parks at annual salary of $1,500. Born in Switzerland, Wirth became an experienced horticulturalist with jobs in London, Paris, and New York City before coming to Hartford. Wirth and his family lived on the second floor of the Pond mansion. Under the auspices of the park department, a refreshment counter was opened on the first floor and in 1902, a free library operated from the house.

Working with the Olmsted firm as consultants, Wirth developed a master plan for Elizabeth Park that took advantage of all the gardens, trees, and buildings that came with the property. By 1897 Wirth had created a welcoming city park with Victorian ornamental flowerbeds, trees, shrubs, winding roads, rustic bridges, and, in the style of the Olmsted firm, picturesque vistas of the surrounding countryside. He moved existing farm buildings from Asylum Avenue, the major thoroughfare bordering the park to the north, to more central areas, and had new greenhouses erected in 1899 to aid with the plant nursery operations. Within three years, the new nursery had produced more than 240,000 plants.

Establishing the Rose Garden

Wirth had gained experience in Europe as a commercial florist and gardener before emigrating to the United States in 1889. Working in New Jersey as a rose grower and private gardener may have helped him make the decision to create a rose garden at Elizabeth Park. By 1903 construction had started on a 1.25 acre rose garden in the shape of a square with a vine-covered gazebo in the center. The Rose Garden opened in 1904 with 116 beds, each filled with 18 to 60 plants of a single variety. In 1912 a semi-circular section was added to the south side to provide the first testing beds for the American Rose Society, and in 1937 a matching section was added to the north side, bringing the size of the Rose Garden to 2.5 acres. The Rose Garden immediately attracted thousands of visitors with an estimated 215,000 visitors in 1906.

[Interview with Rosarian Steve Scanniello]

Elizabeth Park Adds Amenities

In January 1906 George A. Parker, was appointed Hartford’s park superintendent, having served as the superintendent for Hartford’s Keney Park for ten years. Concentrating on the benefits of active recreation, Parker was responsible for introducing courts and fields for organized athletic events, and for leading efforts to move child’s play out of the streets and into the parks and playgrounds. Immigrant and poor children often played a multitude of unsupervised games in Hartford’s streets; and, as automobile traffic grew, such play became increasingly dangerous. Parker argued in 1912 that the city should provide a playground in every neighborhood that had 600 children or more under the age of 12. By 1918, Elizabeth Park held the only year-round playground in Hartford, located on the East Lawn. As the park was just about two miles from the city center, Hartford’s trolley lines brought visitors there from all over the city.

Elizabeth Park’s first formal athletic facilities appeared between 1908 and 1911 when Parker added baseball diamonds and a football grid iron to the former sheep pasture. Ice skating—for both for figure skating and hockey—was encouraged. Curling, lawn bowling, tennis, and croquet became popular sports during the 1910s and 1920s. Parker added a full-sized curling pond in 1912 and a lawn bowling green in 1914. Tennis courts were introduced in 1914, and the park’s first croquet matches were held.

Although the Park now offered many new opportunities for sports, the gardens were not neglected. In 1911 four new gardens were added, including those for alpine plants, perennials, and evergreens and shrubs.

The Era of the WPA

Beginning with the stock market crash of 1929 and continuing until the start of World War II, city finances were strained. Funding for new projects in the parks shifted to federal emergency work programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which from 1935 to 1942 provided funding to states and municipalities to undertake construction projects that would put unemployed men to work. George F. Hollister, Hartford’s third parks superintendent (1926 – 1954), took full advantage of the WPA program (1935 – 1942) to undertake infrastructure projects such as drainage and road paving along with construction of new buildings. Hollister announced in 1936 that the rose garden would be enlarged by the WPA at no cost to the city. Otherwise expensive building materials were salvaged from old buildings or demolitions to cut costs. The Hartford Courant in 1935 reported that the bricks used in the new lawn bowling clubhouse were taken from an old building at Hartford’s Northeast School.

The comfort station was built by the WPA in 1939 of rich brownstone and a slate roof, reminiscent of English architecture. The designer, Hartford architect Russell F. Barker (1873 – 1961), designed dozens of nearby homes and schools. Barker had worked for both the city and state parks departments. Born in Hartford, he trained as a draftsman in Hartford architectural firms before becoming a licensed architect. He was paid $200 for the architectural drawings for the comfort station. Costing a total of $35,429 with $22,713 coming from the WPA program, the building opened in 1940. Unused in recent years, the building was adaptively reused in 2020 as the Garmany Visitor’s Center, a $1 million investment that will serve the public for decades.

Friends of Elizabeth Park to the Rescue

In 1954 landscape architect and rosarian Everett Piester became the parks superintendent. In the same year, the landmark Pond mansion was condemned and demolished, despite vigorous opposition. A new multi-purpose building, now the Pond House Café, was designed by architects Huntington & Darbee in 1959 and built at a cost of $100,000. By 1970, with the city’s population at a 20-year low, support for parks declined and in 1977, the historic rose garden was threatened.

But help was on the way. Friends of Elizabeth Park formed and immediately began fundraising to save and improve the park. In 1983 Elizabeth Park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Friends became the Elizabeth Park Conservancy in 2012. This successful public-private partnership between the City of Hartford and the non-profit conservancy has invested in the park to maintain the gardens, restore buildings, add new amenities, and provide the public with education and arts programs.

Looking to spend a day outdoors? Start at the Garmany Visitors Center to learn more about the park then take a stroll around the 100 acres-brimming with gardens of many types-perennials, shade plants, roses, dahlias, as well as the herb garden. Get lunch or a snack at the Pond House Café and enjoy the pond view from the patio. Interested in tennis or lawn bowling? Go for it! All this beauty and fun due to the generosity of Hartford businessman Charles M. Pond over 100 years ago.

Mary Donohue is assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored and an architectural historian. She co-hosts Grating the Nutmeg.

Explore!

“Connecticut’s Historic Rose Gardens,” Winter 2017-2018

“Off the Streets & Into the Parks” Spring 2003

“Frederick Law Olmsted in Connecticut,” Spring 2018

Read all of our stories about the historic Connecticut landscape on our TOPICS page

Subscribe to the Print Magazine/Buy Back Issues

Sign up for our Free bi-weekly E-Newsletter