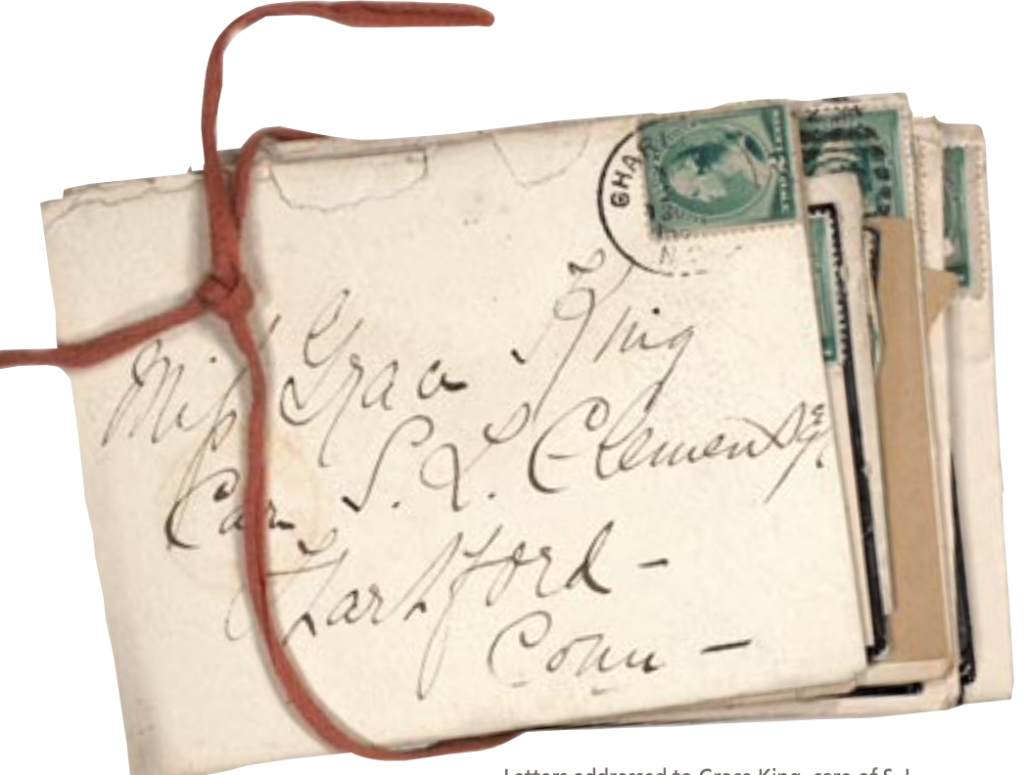

Letters addressed to Grace King, care of S. L. Clemens in Hartford. King Papers, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge

By Miki Pfeffer

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

With a critical eye and a rapier wit, Southern writer Grace King (1852 – 1932) scrutinized “Yankee” ways in Hartford from her perch as the houseguest of her literary mentor Charles Dudley Warner of The Hartford Courant and his wife Susan Warner and their neighbors Sam and Olivia Clemens—Mark Twain and his wife Livy. King, a New Orleans author renowned for her fictional portrayals of Louisiana Creole culture, filled letters to her genteel but impoverished family back home with spicy gossip that provide a frank and unvarnished view of life in Hartford in the 1880s and 1890s. King had remarkable access to the interconnected residents of the idyllic Nook Farm neighborhood. “You never heard in all your life such curious histories as these men and women have,” she wrote, “—not scandals—but divergencies of religious, political and social opinions. I enjoy supremely seeing and studying them.” In a charitable moment she wrote, “Dear me! these people were the quintessence of elegance,” but resentment of their privileges also bubbled up from below her polite surface. She visited Hartford in 1887, 1888, and briefly in 1891.

From the Warner house on Forest Street in 1887 she watched a fragile Harriet Beecher Stowe, then in her late 70s and possibly suffering from dementia, and surveyed Stowe’s provocative half-sister Isabella Beecher Hooker. She enjoyed the company of Warner’s brother George and his wife, Elisabeth “Lilly” Gillette Warner, sister of actor and playwright William Gillette. She gauged the power of Civil War general, former governor, sitting four-term U.S. Senator, and Warner’s co-owner of The Hartford Courant Joseph R. Hawley.

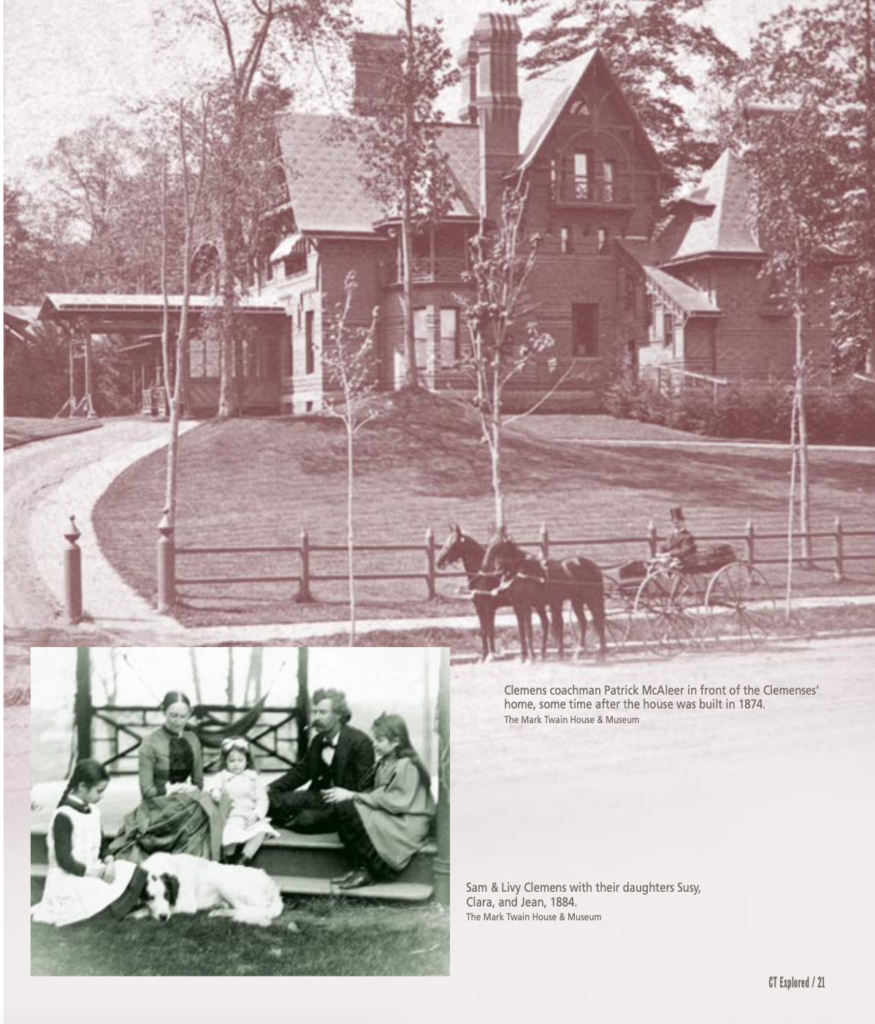

Charles Warner and King shared many a “rousing walk,” a practice that made her feel “more like Grace King and not so much like a woman in a novel.” It was the perfect vantage from which to admire the neighborhood’s grand houses, “all handsome sitting back from the street on large undulating lawns.” On June 5, she wrote to her sister Nan: “Mr. Warner showed me his old residence where he wrote ‘My Summer in the Garden’ & there was the garden too,” at the Thomas Clap-Mary Beecher Perkins house on Hawthorn Street (later, Katharine Hepburn’s girlhood home). Then, “coming home we met Mark Twain—he walked along with us—and of course kept me giggling all the time. He talks just as he writes,” she reported. “His anecdotes are always a little risqué.” King knew that Twain and Warner were next-door neighbors and friends, but she had little reason to expect that now she would enjoy a decades-long friendship with Clemens, Livy, and their daughters Susy, Clara, and Jean.

top: Clemens coachman Patrick McAleer in front of the Clemenses’ home, some time after the house was built in 1874. bottom: Sam & Livy Clemens with their daughters Susy, Clara, and Jean, 1884. The Mark Twain House & Museum

King appreciated the generosity of her hosts but also noted deficiencies in meals or ceremonies that for her social family were markers of status and style. To her sister May on June 1 she wrote that “never before did the contrast between the North & the South appear so distinct as in these little entertainments.” The lunch at the Warners’ was “scalloped lobster—tea, brown bread and white bread with butter and raspberry preserves, all served with the quaintest nicety in the artistic bric-a-brac china of the house. I am going to get some nice recipes for you from the cook here. She is Swedish and a perfect cordon-bleu.” Final assessment, however: “Nice—but small.”

Warner had savored many abundant meals at the Kings’ table in New Orleans—he often supplied the mint juleps—where they had all become friends when he visited the city in 1885 for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. He had encouraged King, then a fledgling 30-something writer, and placed her first short stories, “Monsieur Motte” with the New Princeton Journal and “Bonne Maman” with Harper’s, two publications for which he also wrote.

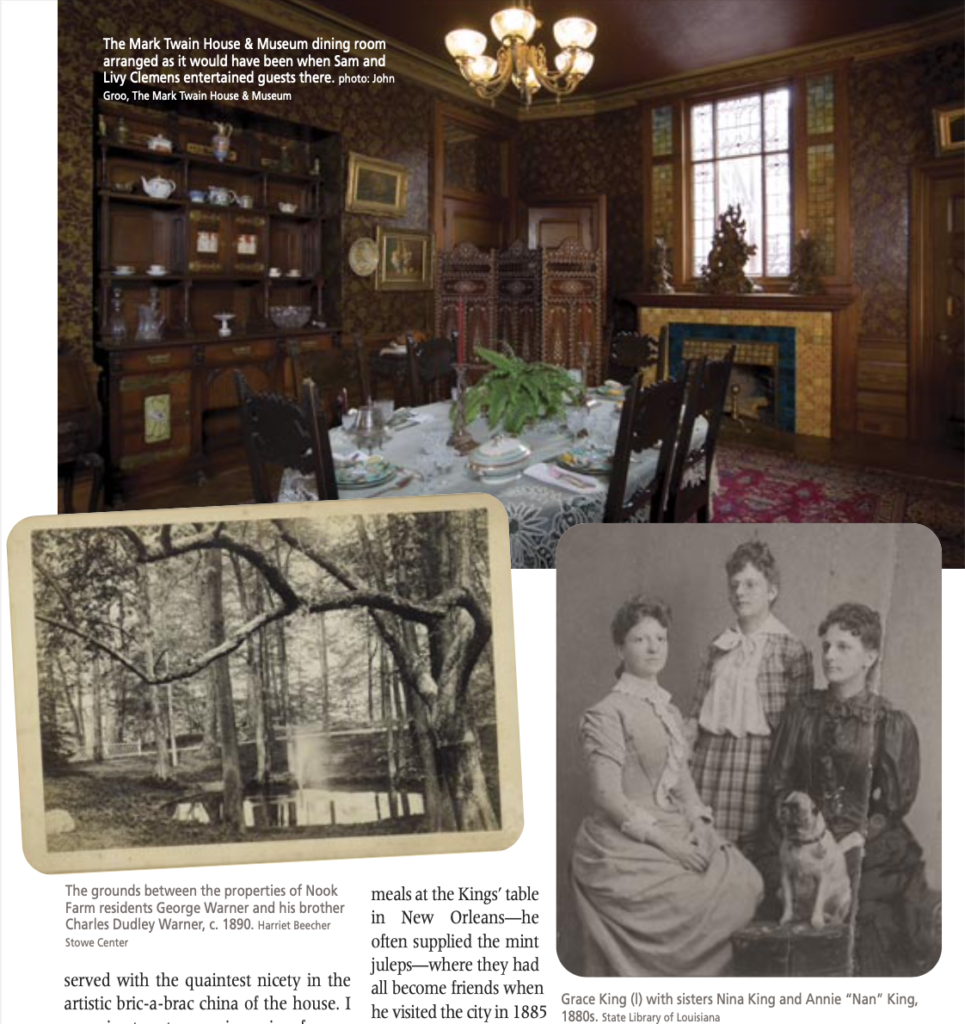

While visiting the Warners in 1887, King was invited to dine with the Clemenses. On June 1 she wrote to her sister Nan about that dinner honoring her and Union General Lucius Fairchild, a pompous “Blatherskite,” in King’s opinion. During the meal, he glorified his Grand Army of the Republic and ranted about President Grover Cleveland. Politically, the two honorees were poles apart. Livy Clemens was appalled when she realized she had paired an outspoken “Radical Republican” with an unreconstructed Southerner, but King was amused and held her tongue. The marvelous feast began with olives, salted almonds, and bonbons served in curious dishes and wine in quaintly shaped decanters. King described the dinner in great detail: fresh salmon in white wine sauce, sweetbreads in cream, broiled chicken, green peas, and new potatoes, followed by whipped cream and “strawberries the size of walnuts.” “The butler in full evening dress served from the side table, and I assure you each plate was simply a chef-d’oeuvre of artistic porcelain. Their cook must be a French one, never in [New Orleans] have I seen such beautiful dishes & such exquisite flavorings.” Nevertheless, she commented on small portions elsewhere. At a dinner at George and Lilly Warners’ in late June, she wrote Nan, “How these people live on so little is a great mystery to me.” King took two servings of liver, hoping that “like the miracle of the widow’s crusts … [it]would be renewed in my stomach with the next morning’s breakfast.”

King also described a full social calendar of entertainments and diversions. Susan Warner, an accomplished pianist, arranged elegant musicals. Neighbors regularly trod private paths between houses for games of chess, whist, charades, and hearts, “about which Mr. Clemens has gone crazy. He insists upon playing it every night; and almost all night.” Sometimes, “’Mark’ got down in his usual position on the rug in front of the fireplace & we all had a mighty nice time.”

One of Sam Clemens’s favorite activities was to give readings of Robert Browning. On Wednesday mornings, King joined neighborhood ladies for “the Browning,” where Clemens read poetry as listeners followed along in their books. “He has a great talent for it, and his voice is simply grand,” she reported to Nina in mid-June. “Mr. Clemens is so good natured and good hearted—he seems never to think of doing anything but what his wife wants for the amusement of people. They have the nicest children I ever saw.” King loaned the Clemens girls French plays and sheet music from her own collections, taught them a dance, and earned a pet name: “Teety,” rhyming with sweetie.

King was charmed when the persona “Mark Twain” emerged. “Mr. Clemens is of course at his best at table” she wrote her mother in October, “and he just talked along as if he were writing another ‘Innocents Abroad.’” King named Livy “the best of companions,” a woman of good heart and great kindness, a “perfect housekeeper—ordering her servants & family marvelously for such a delicate little thing.” She wrote that she and Livy shared confidences on the “ombra” of the Clemenses’ house on Farmington Avenue.

King spent six weeks in the Warners’ home and months more boarding at the Elm Tree Inn in Farmington, occasionally making short visits outside Connecticut. About her first overnight stay with the Clemenses on October 8, King excitedly wrote to her mother:

I certainly cannot go to sleep tonight without giving you a little account of my gorgeous surroundings. You must know that I am at the Clemens; came over for dinner today. I have a large bedroom, a large dressing room, & a bathroom with every accomplishment in the way of toilet and bath. The maid has hung up my dresses and placed all my things for the night on the dressing tables. There are lights lighted everywhere, and I do feel very much like Beauty did when the Beast left her alone in the palace.

She declared, “I could easily live in Hartford, the people are all so nice.”

Despite disdain for the way Harriet Beecher Stowe portrayed the South in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, King was able to marshal sympathy for the famous writer, whom she saw “wandering around under the trees” gathering wildflowers. Stowe’s face seemed “more spiritual than her pictures. Her short grey curls flutter as she walks from under the frills of velvet … her hands full of flowers, or tightly clasped looking straight up at the heavens, walking on very fast. Her figure is slight, erect and graceful—she walks like a girl.”

King was less charitable when she met Stowe’s daughter, Hattie, over a game of whist. “I could not devote much attention to my cards, I was so interested watching this daughter of the celebrated Harriet Beecher & the niece of Henry Ward [Beecher]. A perfectly woodeny, hard featured coarse-grained cross old maid. She was so anxious to gossip and retail her little scandals of the neighborhood that she never could remember what trumps were. … I kept wondering how a woman of genius could have such a daughter & came to the conclusion that she could not be a woman of genius—that is all.”

One neighbor intrigued King above others: Isabella Beecher Hooker, especially since “Mr. Warner had laid down his orders that I was not to be taken to see Mrs. Hooker or have anything to do with her. She is one of his archrivals,“ King wrote to her sister May early in her 1887 visit on June 22. She chortled that Hooker was “a dreadfully unorthodox old creature!” and “a spiritualist and every other kind of ‘ist’ that a woman ought not to be.“ Hooker seemed “no doubt thoroughly lovable” and her personal character above reproach. “It is only her intellect that is unorthodox. She has never insinuated any of her theories or practices to me, to my disappointment for they say she is a most astonishing expounder of advanced views.” The spicier gossip was this: “Mrs. Hooker is the intimate friend of Victoria Woodhull and an ardent ‘free love’ and woman’s rights female & a spiritualist & I do not know what else besides; To tell you the truth I can’t separate & identify these women at all but there are great shakings of head whenever she is mentioned hereabouts.”

King and Hooker thought they might share genealogy because Hooker said her mother was a King. And she offered organizing tips, King wrote her sister May in late July. “I must arrange the facts of my knowledge so that I can get them at a moment’s notice” by putting all pertinent clippings into separate envelopes and creating an index for each. Hooker “also has her whole life done up, year by year in little copy-books of her own making. This I must do also, if I wish to make my life of service—She read me a good many pages from hers—as far as I can see she has been more of a meddler than a worker in life. I got my information and left after really a very interesting time.”

top:The Mark Twain House & Museum dining room arranged as it would have been when Sam and Livy Clemens entertained guests there. photo: John Groo, The Mark Twain House & Museum. bottom left: The grounds between the properties of Nook Farm residents George Warner and his brother Charles Dudley Warner, c. 1890. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. bottom right: Grace King (l) with sisters Nina King and Annie “Nan” King, 1880s. State Library of Louisiana

King claimed a “fancy” for Hooker’s “quiet plain unassuming handsome old” husband John Hooker, who with Francis Gillette founded the Nook Farm neighborhood in which the Warners, Clemenses, and other prominent Hartford families lived, “but I hear that he was a devoted abolitionist and had endured obloquy and humiliations in the Anti Slavery fight.” King attended the Hookers’ 50th wedding anniversary in 1891.

King entertained her family with gossip they were not to repeat in public. Lilly Warner was a favorite but “a puritan of puritans” and her mother “a prim old Quakeress.” Mrs. Twichell, wife of Twain’s pal, the Reverend Joseph Twichell of Asylum Hill Congregational Church, was “a very nice woman who has broken down suddenly in heart principally because she has had the foolishness to undertake to bring in the world and take care of nine children—on a minister’s salary.”

To King’s well-read family, she quipped, “You must not suppose that the people here read much. They seem to know all about literary people and the names of books, but they have not a ‘connaissance approfondie’ [deep or thorough knowledge]of anything in particular.” Furthermore, “These people here do not seem to know or care much about politics, religion, or the South—They are as easy going as it is possible for people to be. They have the contented expression of face and speech of souls assured of salvation in the next life and prosperity in this. Having both soul and body in sight of damnation, I do not feel so much at my ease, and in fact a little déclassée.”

King was critical of others but could also be self-deprecating. “Mrs. Warner & Mrs. Clemens are so English in their pronunciation & intonation that I feel like a squeaking Manatee,” she wrote to sister May on June 7, 1887. She lacked confidence, had to get over timidity to “‘talk back’ & have lots of fun” around Twain. She was afraid her clothes wouldn’t measure up among the wealthy, so her three sisters lent their best. “Tell Nan that if she can’t get to know the Clemens her clothes can,” King jested. “Of course the people up here have too little ‘fancy’ in dress as in everything else. The aim of life seems to be a respectable uniformity and I must say they hit the mark exactly—I can understand now why the literature of the North is so devoid of colouring and poetry.”

King’s family was also politically attuned to her region’s Democratic voting practices. When she returned to Nook Farm in election year 1888 to spend autumn with the Clemenses, she wrote Nan that Twain punctured “the staidest and most respectable people” of its “pretty close set.” Some had “got ahead of Mark in several transactions. After the next election he is going to cease his citizenship of Hartford, and become a citizen of Elmira, because they removed the electric lamp from in front of his house, to put it before the [politically influential Franklin]Chamberlain’s. He said he would do it before the election day, but he wants to have the pleasure of voting for Cleveland,” for a second term.

Vote Democratic he did, to the horror of most neighbors and the delight of King. She wrote that Warner, on the other hand, voted the straight Republican ticket because of General Hawley’s sentiments, but she suspected he might be a “Mugwump” in his heart. He had seemed amenable in New Orleans.

King was grateful to the Warners and their friends for showing her “something of the fashionable society of Hartford” and its gilded mansions on neighboring Woodland Street. She had attended tea at the “perfect palace” of Elizabeth Jarvis Colt across town, with its jewels and gifts that European royalty and celebrities sent to Colt’s gun-manufacturing husband Samuel before his death in 1862. “Making firearms, you see, is work the crowned heads appreciate.”

King had seen fabulous fabrics at the celebrated Cheney Brothers silk mills in Manchester. “The weaving rooms were almost as tempting to me as if Satan had taken me up to the top of a mountain and promised me the world.” She had seen Hartford’s “magnificent white marble capitol” and the dedication of a statue of Nathan Hale with its upward eyes, outstretched hands, and feet poised to mount the scaffold and speak his memorable line. But King quipped, “I thought it was ideally beautiful but after a while I tortured myself by fancying that was just the way he must have looked dangling at the end of the rope.”

She had met writers, publishers, and editors through Charles Warner who would help her publish volumes of short stories (Balcony Stories is her best-known), a novel, memoir, and books of genealogy, biography, and history. “What would my life be now without that trip?” King wrote Susan Warner upon her return home in 1887. The visit had been a respite and had expanded her world. “My love with my thoughts go all over Hartford—but they come home to roost at Nook Farm and its ‘farmers’ (farmers of the heart).”

Miki Pfeffer edited A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court: Letters from Grace King’s New England Sojourns (Louisiana State University Press, 2019), upon which this story is based.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Mark Twain HERE or on our Notable Connecticans TOPICS page

“Nook Farm: Where Mr. Twain and Mrs. Stowe Built Their Dream Houses,” Summer 2011

The Mark Twain House & Museum

351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford

marktwainhouse.org

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

77 Forest Srteet, Hartford

harrietbeecherstowecenter.org

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS