(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

It’s a humbling realization, really, for one who has become a preservationist and architect and has worked on the restoration of another of Cass Gilbert’s significant buildings, Waterbury City Hall. When I came to New Haven in 1975, I never even noticed Union Station.

Of course, that was largely because Gilbert’s 1918-1920 railroad station was, at least to the traveler arriving by train, closed. There was talk of its demolition. The only experience I had with the structure at that time was an occasional trip through a low, lightly built, minimal modernist anteroom to the platform-access tunnel. Not memorable.

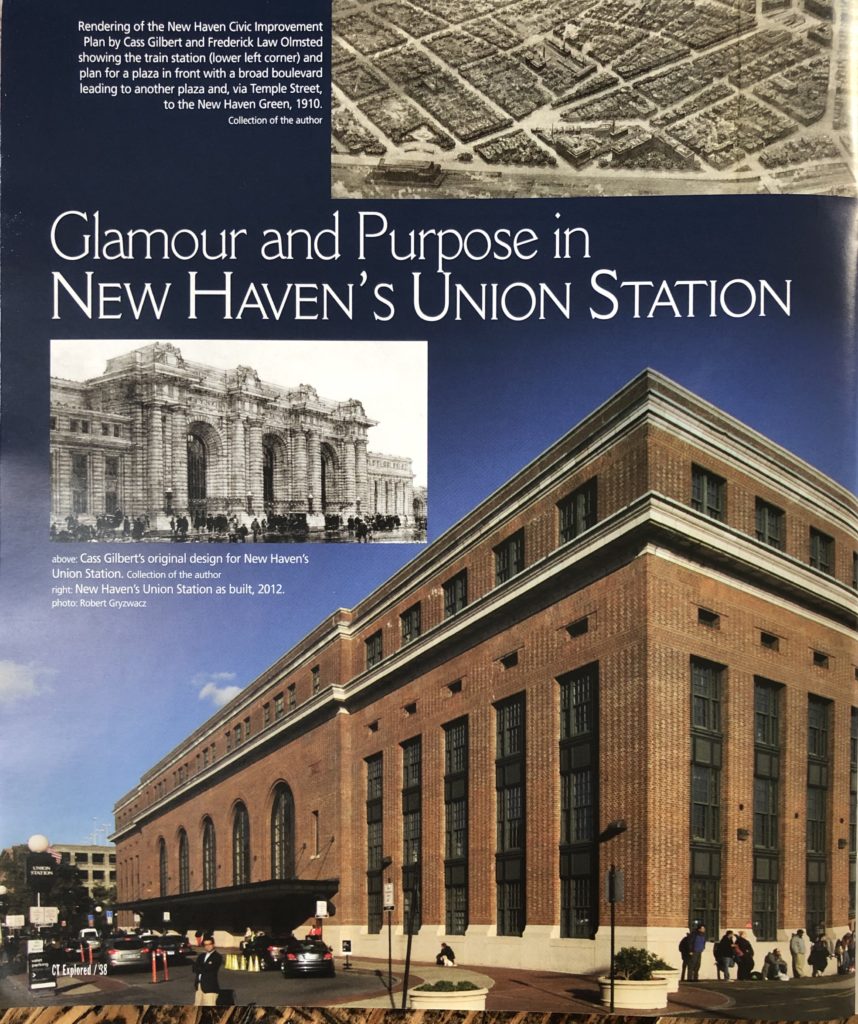

Union Station deserved better. Conceived by Gilbert as a grand entry to the city, New Haven’s new train station was to be monumental in the Beaux Arts tradition first made popular in this country by the Chicago World Columbian Exposition of 1893 and exemplified by terminals such as New York City’s 1913 Grand Central Terminal. Unlike Grand Central, New Haven’s Union Station was to have a proper setting. It would have a plaza in front, much like Daniel Burnham’s 1908 Union Station in Washington, D.C. It was intended to set a visitor’s first impression of New Haven.

And what an impression that would have been. The original plan called for visitors to exit the station and plaza via a broad boulevard, the terminus of which was to be another plaza right at the edge of the city’s original nine-square plan, where Temple Street would direct you to the green. All of this was carefully spelled out in a 1910 report to the Civic Improvement Commission by Gilbert and landscape architect Fredrick Law Olmstead (of Central Park fame).

It was not to be. A grand plan was not the priority of then Mayor Frank J. Rice, and implementing a plan of its scale would have required great vision and substantial financial resources. Making matters worse, the mayor and citizens backing the plan also had some personal animosity between them. There was to be no plaza in front of Union Station and no boulevard linking it to the center of the city.

But where the public sector faltered, the private succeeded in at least getting the station built. Since the turn of the century, the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, which essentially controlled all New England transportation south of the current line of the Massachusetts Turnpike, had been investing mightily in both improvements and expansion. The railroad company built a new station in Providence in 1898 and the new South Station in Boston in 1899. From 1903 to 1913 it spent $120 million on improvements—including Grand Central in 1913—and another $204 million on acquiring competitors at a time when a good middle-class annual income was about $1,000. It also rebuilt the entire line from New Haven to New York, increasing it from two tracks to four and electrifying the line. The New Haven Railroad, backed by financier J.P. Morgan, was “can do”—and it did.

New Haven’s station was projected to cost $1.5 million. By 1918, however, World War I and post-war inflation reduced the buying power of the railroad’s money. It can be inferred that costs needed to be cut. Earlier Gilbert studies for the exterior show a more robust modeling of the entry façade, with four projecting piers of paired columns capped by monumental sculptures framing three heroically scaled recessed arched portals. One can imagine the intended marble cladding and ornament as Gilbert used in Waterbury, but on a much grander scale. As built, the façade is much plainer (and planer), with a barely projecting base and a strong but simple cornice, no doubt intended as marble but executed in terra cotta. Even so, great care was taken in obtaining maximum character from carefully articulated brickwork. The great arches consist of cascading archivolts of modulated widths.

The station’s interior might be considered New Haven’s grandest room, at 115 feet long with a great gilded coffered ceiling. Here, too, there were likely economies. The walls appear to be travertine, but are in fact faux, but sufficiently convincing that even careful examination does not disappoint for want of quality.

The 1983-1986 restoration by Herbert Newman Architects, overseen by the firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, resurrected Gilbert’s original design. It also installed a canopy over a passenger drop-off area that had been intended by Gilbert but that was likely lost to budget concerns. Finally, as befits a commuter-oriented station, the restoration streamlined train platform access with a new enlarged tunnel connected to the waiting room with high capacity escalators, which any of us, returning weary from a long day in New York City, greatly appreciate. This is a fully modern addition and completely underground so it is never viewed in conjunction with the Gilbert structure. With its ovoid cylinder formed by linear aluminum slats, it is representative of design of its time and, for that reason, interesting in its own right.

We can be grateful to Gilbert for his foresight and for his inspired design that works as well today, and is as important civically, as when it opened 93 years ago. And, we can be grateful that such a structure was kept in the public realm by a sensitive restoration.

Robert W. Grzywacz is vice president of the Architecture Studio of DeCarlo & Doll with a focus on restoration and the design of urban structures. He wrote “Putting Waterbury City Hall Back in Commission” in the Fall 2011 issue.