(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Gideon Welles, born in Glastonbury in 1802 and a longtime Hartford resident, was a bred-in-the-bone Connecticut Yankee whose first American ancestor, Thomas Welles, was an early settler of Hartford and the fourth man to serve as governor of colonial Connecticut. As befit his heritage, Gideon was dignified and somewhat austere in manner, a person of stern moral rectitude, high-minded, judgmental, and sometimes self-righteous. He also had a strong sense of civic duty and an abiding conviction that politics should be about principle, not just the pursuit of power and patronage.

During the pre-Civil War decades Welles was one of Connecticut’s leading journalist-politicians. A founder of the state’s Democratic Party, he edited its leading organ, the Hartford Times, from 1826 to 1837, contributed to it for more than a decade thereafter, served in the state legislature, was a shrewd party operative, and received patronage appointments from Presidents Jackson and Polk. From the late 1840s onward, however, he grew increasingly disenchanted with his party, believing it was being hijacked by the southern “Slave Power” and its “doughface” northern allies. Ultimately, he abandoned the Democracy and in February 1856 joined with other disaffected Democrats, former Whigs, and Free Soilers to launch the Republican Party in Connecticut. He promptly established the Hartford Evening Press to be its mouthpiece. Although declining the editorship, he wrote many of the paper’s editorials during its start-up phase. Owing in part to his persistent efforts as organizer and advocate, the fledgling party carried the state in the 1856 and 1860 presidential elections and in 1858 elected William A. Buckingham to the first of eight consecutive one-year terms as governor.

When Welles is remembered today, however, it is usually for his service as Lincoln’s secretary of the navy and for the diary he kept, beginning in the summer of 1862 and continuing through Andrew Johnson’s administration. (Only Welles and Secretary of State William H. Seward served in the cabinet throughout both administrations.)

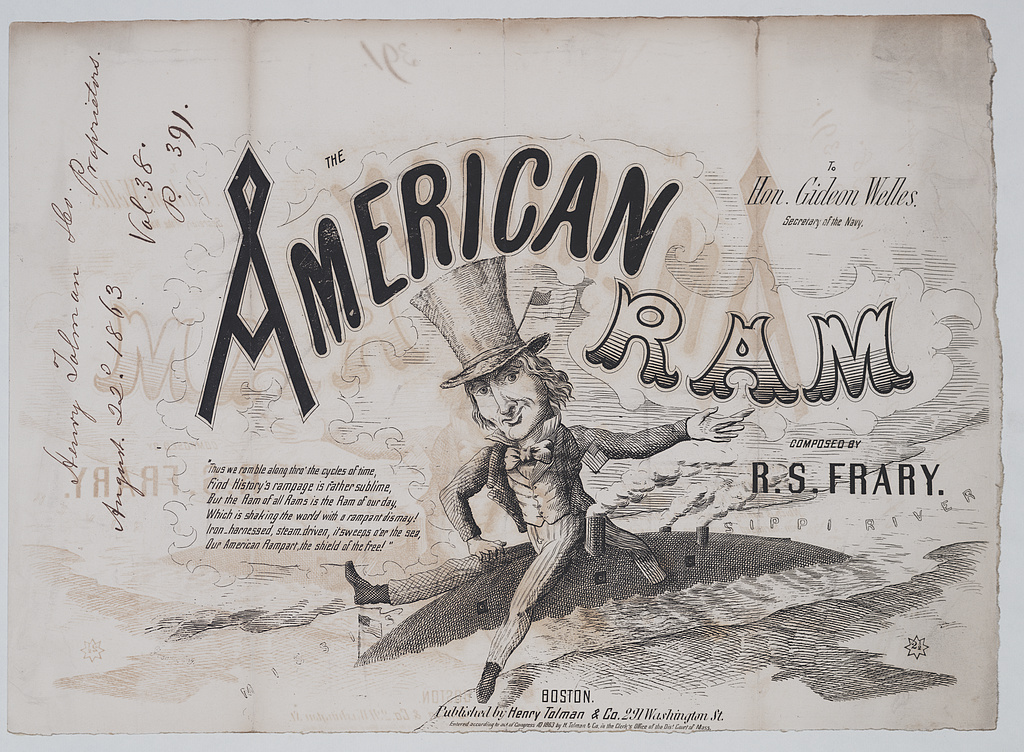

Although Welles was often second-guessed by armchair admirals in the press, skewered by cartoonists, and blamed by ship owners and merchants for their losses at the hands of Confederate commerce raiders, most historians rank him as an important architect of Union victory. They credit him with pushing for the construction of ironclad warships (beginning with the famous USS Monitor), organizing and managing an increasingly effective blockade of the Confederacy, and replacing older, tradition-bound naval officers with younger, more-flexible men.

Welles’s diary is indispensable for understanding the Lincoln administration and wartime politics – a wide-ranging and candid insider’s account of which innumerable historians have made use. First published in 1911 in three volumes totaling nearly 1800 pages, about half of them covering the wartime years, it is written in vigorous, sometimes tart prose and studded with shrewd observations about men and measures.

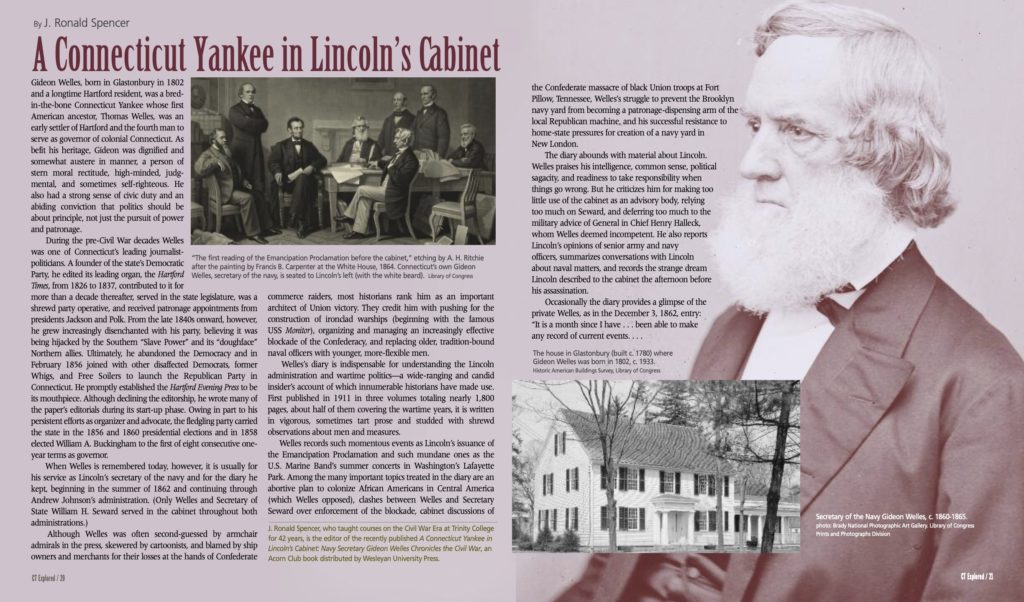

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, c. 1860-1865. photo: Brady National Photographic Art Gallery. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Welles records such momentous events as Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation and such mundane ones as the U.S. Marine Band’s summer concerts in Washington’s Lafayette Park. Among the many important topics treated in the diary are an abortive plan to colonize African Americans in Central America (which Welles opposed), clashes between Welles and Secretary Seward over enforcement of the blockade, cabinet discussions of the Confederate massacre of black Union troops at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, Welles’s struggle to prevent the Brooklyn navy yard from becoming a patronage-dispensing arm of the local Republican machine, and his successful resistance to home-state pressures for creation of a navy yard in New London.

The diary abounds with material about Lincoln. Welles praises his intelligence, common sense, political sagacity, and readiness to take responsibility when things go wrong. But he criticizes him for making too little use of the cabinet as an advisory body, relying too much on Seward, and deferring too much to the military advice of General in Chief Henry Halleck, whom Welles deemed incompetent. He also reports Lincoln’s opinions of senior army and navy officers, summarizes conversations with Lincoln about naval matters, and records the strange dream Lincoln described to the cabinet the afternoon before his assassination.

Occasionally the diary provides a glimpse of the private Welles, as in the December 3, 1862, entry:

It is a month since I have . . been able to make any record of current events. … A light, bright, cherub face, which threw its sunshine on me when this book was last opened, has disappeared forever. My dear Hubert [age four], who was a treasure garnered in my heart, is laid beside his five brothers and sisters in [Hartford’s] Spring Grove [Cemetery]… . Alas, frail life – amid the nation’s grief I have my own.”

One element of the diary on which historians and Lincoln biographers have often drawn are Welles’s sharply etched, adjective-laden, often perceptive but sometimes unfair characterizations of cabinet colleagues, prominent politicians, and senior military officers. Secretary Seward, whom Welles conceded had talent but mistrusted as an unprincipled opportunist, is the subject of many critical passages. The September 16, 1862, entry is typical:

He isobtrusive, never reserved or diffident of his own powers, is assuming and presuming, meddlesome, unreliable anduncertain, ready to exercise authority always, never doubting his right until challenged; and then he becomes timid,doubtful, distrustful, and inventive of schemes to extricate himself, or to change his position.”

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton also comes in for pointed criticism, as in the September 12, 1862 entry:

He is impulsive, not administrative; has quickness, rashness, when he has nothing to fear; is more violent than vigorous, more demonstrative than discriminating, more vain than wise; is arrogant and domineering towards those in subordinate positions . . . but is a sycophant and intriguer in deportment and language with those whom he fears. ”

Initially, Welles admired Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, but later became highly critical of him. This is exemplified by a passage written in August 1864, not long after Chase, who lusted for the Republican presidential nomination, resigned from the cabinet in a dispute with Lincoln over a key patronage appointment: “He has inordinate ambition, intense selfishness, and insufferable vanity… . He is irresolute and wavering, his instinctive sagacity prompting him rightly, but his selfish and vain ambition turning him to error.”

Welles recorded similarly acerbic remarks about other political figures. For instance, he dubbed New York’s Democratic governor, Horatio Seymour, “Sir Forcible Feeble” for his inept handling of the July 1863 New York City draft riots. And he labeled Republican Senator John P. Hale, chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee and a frequent critic of Welles’s administration of the Navy Department, a “demagogue, a “constant marplot,” a man full of “spite and malignity,” and a “profligate politician” who is “fond of scandal, delights in defaming, and is reckless of truth in his assaults.”

Welles is also hard on most of the generals and admirals he discusses. A notable exception is Admiral David G. Farragut, whose squadron, led by his flagship, the USS Hartford, took New Orleans in April 1862 and won the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864. ) Of him, Welles consistently expressed admiration. On January 23, 1863, he wrote that Farragut “is a good officer in a great emergency, will more willingly take great risks in order to obtain great results than any officer in high position in either naval or military service.” Later he noted that Lincoln thought Farragut’s promotion to admiral’s rank was the best senior appointment made in either service.

Particularly astute is a series of observations about General George B. McClellan that runs from late August 1862 through the Battle of Antietam on September 17th and into October. In the September 3rd entry Welles identifies what many historians agree was McClellan’s greatest flaw: “To attack or advance with energy and power is not in his reading or studies, nor is it in his nature or disposition to advance. . . . [He] wishes to outgeneral the Rebels, but not to kill and destroy them.”

Welles’s narratives of major wartime events are even more valuable than his portrayals of individuals. A prime example is his description of a conversation he and Seward had with Lincoln on July 13, 1862, during a carriage ride to the funeral of Stanton’s infant son. The president confided that he contemplated issuing a proclamation of emancipation – the first time he had divulged this to anyone in or outside of the cabinet. According to Welles, Lincoln “dweltearnestly on the gravity, importance, and delicacy of the movement, said he had given it much thought and hadabout come to the conclusion that it was a military necessity absolutely essential for the salvation of the Union, thatwe must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued, etc.” After noting that Seward and he agreed with Lincoln, Welles adds that the president entreated them to give the subject “ special and deliberate attention, for he was earnest in theconviction that something must be done.”

“The American Ram,” the cover of sheet music for a song dedicated to Gideon Welles, published by Henry Tolman & Co., 1863. Uncle Sam rides an ironclad steam vessel (or ram) down the Mississippi River. Welles ushered the Union navy into the age of ironclad steamers. Several lines of verse praise the ironclad rams as “shaking the world with rampant dismay! Iron-harnessed, steam-driven, it sweeps o’er the sea, Our American Rampart, the shield of the free!” Library of Congress

Historians often cite this entry because it reveals Lincoln’s sense of urgency about emancipation and pinpoints when he finally concluded that a frontal assault on slavery had become a military necessity and thus constitutionally defensible. Lincoln informed the entire cabinet of his decision nine days later, issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, and the final Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Welles chronicles each of these steps.

Welles also provides a first-hand account of the December 1862 cabinet crisis, when the Republican Senate caucus tried to force Lincoln to oust Seward, partly on the basis of tales Chase had been telling senators about his rival’s supposedly detrimental influence on Lincoln and the administration. Seward promptly submitted his resignation. Warning that the senators’ action was a dangerous intrusion on Lincoln’s executive authority, Welles urged him not to accept the resignation. At a meeting with the cabinet (minus Seward) and the senators the night of December 19, Lincoln put Chase in such an awkward position that the next morning he offered his resignation. Welles was present and recorded the only eyewitness account:

Chase said he had been painfully affected by the meeting last evening … and … informed the President he had prepared his resignation. ‘Where is it?’ said the President quickly, his eye lighting up in a moment. ‘I brought it with me,’ said Chase, taking the paper from his pocket; ‘I wrote it this morning.’ ‘Let me have it,’ said the President, reaching his long arm and fingers towards C., who held on, seemingly reluctant to part with the letter… . ‘This,’ said [Lincoln] … with a triumphal laugh, ‘cuts the Gordian knot.’ An air of satisfaction spread over his countenance such as I have not seen for some time. ‘I can dispose of this subject now,’ he added … ‘I see my way clear.'”

Lincoln proceeded to refuse both Seward’s resignation and Chase’s, which left the senators stymied and the president’s prerogatives intact.

Nothing in the diary is more engrossing than the account of Lincoln’s death, which occupies more than a dozen printed pages. Its you-are-there quality illustrates the sometime journalist’s sharp eye for detail and flare for dramatic narrative.

Welles arrived at the Petersen house across from Ford’s Theater a little before midnight on April 14 and stationed himself in the room to which the dying Lincoln had been carried. He observed,

The giant sufferer lay extended diagonally across the bed, which was not long enough for him. He had been stripped of his clothes. His large arms, which were occasionally exposed, were of a size which one would scarce have expected from his spare appearance. His slow, full respiration lifted the [bed]clothes with each breath … . His features were calm and striking. I had never seen them appear to better advantage than for the first hour … I was there. After that, his right eye began to swell and that part of his face became discolored.”

Welles writes that as death neared, Lincoln’s wife, Mary, made a final visit and his oldest son, Robert, positioned “at the head of the bed … bore himself well, but on two occasions gave way to overpowering grief and sobbed aloud, turning his head and leaning on the shoulder of Senator [Charles] Sumner. The respiration of the President became suspended at intervals, and at last entirely ceased at twenty-two minutes past seven.”

Welles’s description of his visit to the White House the morning of April 15, just hours after Lincoln’s death, is especially gripping:

There was a cheerless cold rain and everything seemed gloom. … In front of the White House were several hundred colored people, mostly women and children weeping and wailing their loss. …Their hopeless grief affected me more than almost anything else, though strong and brave men wept when I met them.

At the White House all was silent and sad. Mrs. W[elles]was with Mrs. Lincoln and came tomeet me in the library. [Attorney General James] Speed came in, and we soon left together. As we were descending the stairs, ‘Tad,’ who was looking from the window at the foot, turned and,seeing us, cried aloud in his tears, ‘Oh, Mr. Welles, who killed my father?’ Neither Speed nor myself could restrain our tears, nor give the poor boy any satisfactory answer.”

The narrative continues through the giant procession that accompanied Lincoln’s body from the White House to the Capitol, where it lay in state in the Rotunda, and the transfer of his remains to the rail depot whence it embarked, in Welles’s words, on “its long, circuitous journey to . . . Springfield, in the great prairies of the West.”

Although Welles remained in office throughout the administration of Lincoln’s successor, he found those years much less satisfying than the wartime years. This was primarily because he, like President Johnson, bitterly opposed the Reconstruction measures the Republican Congressional majority adopted between 1866 and 1868 – measures Welles condemned as unconstitutional and misconstrued as exclusively a product of rank partisanship, unbridled extremism, and fanatical hatred of the South. He had no regrets on leaving the Navy Department for the last time on March 3, 1869, the day before the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant, whom he had come to detest.

Although tempted to remain in Washington, Welles ultimately returned to Hartford. He and Mary arrived by train the evening of April 28 and by late May were settling into the spacious house Welles purchased on Charter Oak Place. On June 6, he recorded his last diary entry. But he continued to wield a prolific pen.

Almost immediately, he began writing articles for the Hartford Times and occasionally the Courant. He also published commentaries in the New York Times and worked at editing the diary. Most important, between 1870 and 1877, he wrote 21 essays on Lincoln and his administration for Galaxy Magazine. In 1874 he expanded three of them into a book, Lincoln and Seward, in which he challenged the then-widespread belief that Seward had dominated Lincoln’s administration.

As the year 1878 opened, Welles was in reasonably good health. But then a carbuncle developed behind one ear. The infection soon spread, and after enduring several days of agonizing pain, he died the evening of February 11. He had outlived Seward, Stanton, Chase, Farragut, the despised John P. Hale, and other of his wartime associates. And thanks to the diary he left to posterity, he achieved a measure of immortality.

Ronald Spencer, who taught courses on the Civil War Era at Trinity College for 42 years, is the editor of the recently published A Connecticut Yankee in Lincoln’s Cabinet: Navy Secretary Gideon Welles Chronicles the Civil War, an Acorn Club book distributed by Wesleyan University Press.

Explore!

A Connecticut Yankee in Lincoln’s Cabinet: Navy Secretary Gideon Welles Chronicles the Civil War is available for $24.95 (paperback) at Wesleyan.edu/wespress.

Read all of our stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page

Read all of our stories about Connecticut at War on tour TOPICS page

“Glimpses of Lincoln’s Brilliance,” Fall 2005