By Pablo Delano

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2023

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

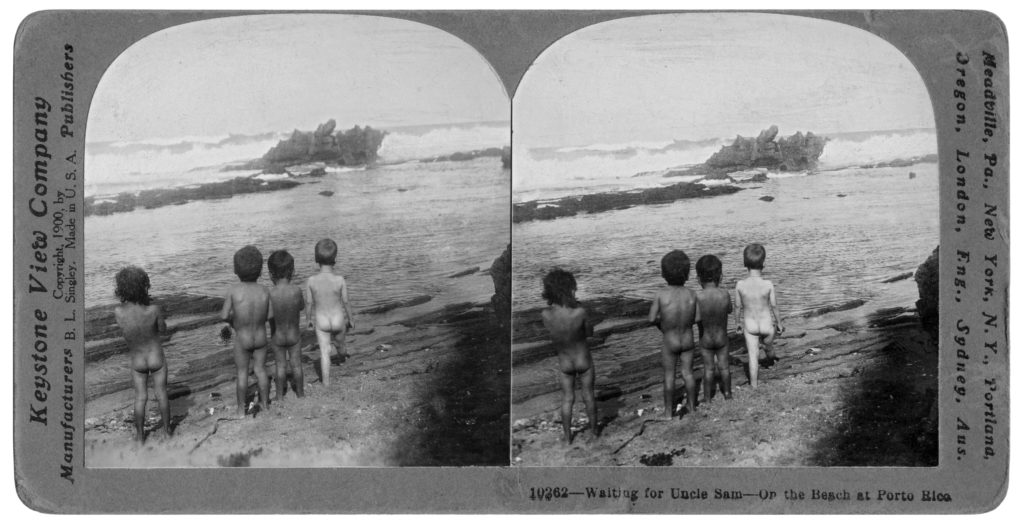

Waiting for Uncle Sam – On the Beach at Porto Rico, stereograph card, The Keystone View Company, 1900 (recto)

![Topsy, from Swedish languae editon of Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Onkel Toms Stuga: En Skildring af de Förtrycktes Lif af Harriet Beecher Stowe [Philadelphia, PA]: John C. Winston, 1897. Collection of Watkinson Library, Trinity College](https://www.ctexplored.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Topsy_pg393-194x300.jpg)

Topsy, from Swedish language edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Onkel Toms Stuga: En Skildring af de Förtrycktes Life af Harriet Beecher Stowe [Philadelphia, PA]: John C. Winston, 1897. Collection of Watkinson Library, Trinity College

The play they were offering was advertised as El Gran Drama Americano: La Cabana de Tio Tom, and as I had seen it a year before in Key West, performed by an amateur troupe of negroes, under the more familiar name of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, with a “Little Eva” who was as black as coal and whose hair was as kinky as wool, I cherished a tender memory of the play and regretted not to see it in Spanish.

Stumbling upon this text, I wondered what exactly spurred Mr. White’s regret to have missed the Puerto Rico performance. Perhaps he was curious about the precise skin color and hair texture of the Puerto Rican actors, or about how the characters of Little Eva or Topsy might be portrayed by Spanish-speaking, “newly made Americans” (as Puerto Ricans were sometimes referred to at the time).

Uncle Sam’s Island Possessions is but one of countless books, articles, artifacts, and stereograph cards produced in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War for the purpose of celebrating, popularizing, and justifying the United States’ imperial expansion. These documents were modeled on those produced by other imperial powers and drew upon such concepts as the inherent racial and moral superiority of white people. As a visual artist from Puerto Rico, I find these materials repugnant, but also fascinating and worthy of study because they shed light on the methodology of oppression employed by the colonizer.

It occurred to me that the colonizer’s gaze could be turned back upon itself and play a role in the decolonial work of my art practice. So, I began to employ these materials and use them directly in my artworks. The resulting project, The Museum of the Old Colony, integrated large-scale reproductions of historical images and texts into a conceptual art installation that adopted the trappings of a museum. The artwork is intended not only to expose and denounce U.S. colonial rule in Puerto Rico but also to evoke the complicity of museums in serving the cause of empire. There is an ironic twist to the title The Museum of the Old Colony: “Old Colony” refers not only to the colony itself but to a popular brand of soft drink originating in the southern U.S. during the mid-20th century but now manufactured and sold exclusively in Puerto Rico.

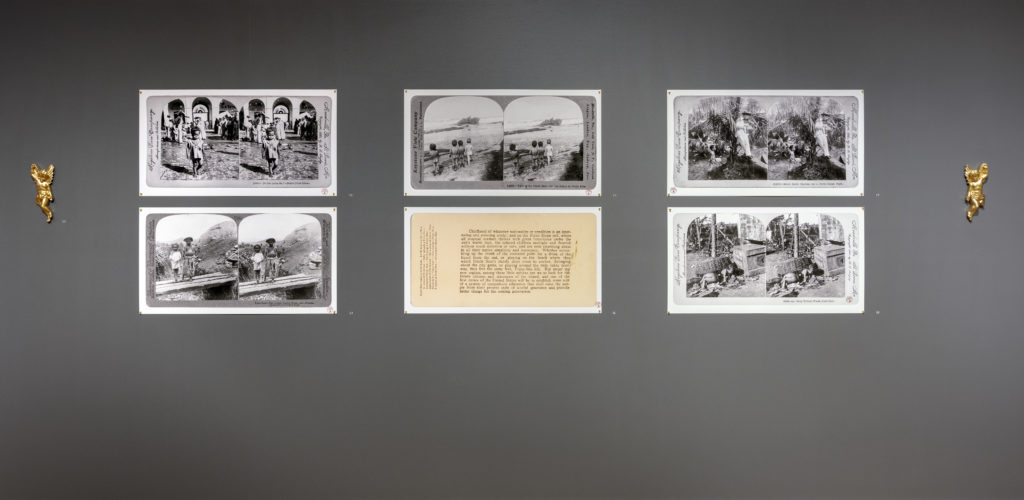

Installation detail showing reproduced stereograph cards, The Museum of the Old Colony: An Art Bottom row center image depicts the verso of the stereograph card Waiting for Uncle Sam – On

Installation by Pablo Delano, Duke Galley of Fine Arts, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, 2022. the Beach at Porto Rico, seen above it. Pigment prints on rag paper, each is 36” wide. photo: Pablo Delano

Books like Uncle Sam’s Island Possessions, along with hundreds of stereograph cards published in the wake of the Spanish-American War, presented Puerto Rico through an intensely racialized and condescending lens. By the time the U.S. invaded Puerto Rico, Connecticut-born Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin had achieved the status of best-selling novel of the 19th century. Its anti-slavery message had already influenced the trajectory of U.S. history. The novel also spawned many dramatized versions; stage productions known as “Tom shows,” none of which was endorsed by Stowe. Some of these productions remained true to Stowe’s abolitionist message, but others subverted the story into a pro-slavery narrative that mocked the enslaved and enacted derogatory, racist stereotypes. In this broad context, references to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or any of its characters, would have been readily understood not only by readers of Uncle Sam’s Island Possessions but also by consumers of any of the plethora of contemporaneous materials marketed to popularize the notion of the U.S. as a benevolent colonial overlord.

In Stowe’s novel, a disobedient, seemingly incorrigible slave girl named Topsy is purchased by the slaveholder Augustine St. Clair to be given to his cousin Ophelia as a kind of social experiment. Topsy remains stubborn, resisting all attempts at education or reform until offered unconditional love by Eva, Mr. St. Clair’s daughter. By accepting Christianity, and Eva’s unconditional love, Topsy transforms into a “civilized” being. Thus, both directly and indirectly, the character of Topsy became a metaphor for what U.S. authorities saw in their infantile, unhygienic, undisciplined but perhaps redeemable newly acquired colonial subjects: the people of Puerto Rico.

A blatant example of this metaphor that I include in my artwork The Museum of the Old Colony, is the 1900 stereograph card published by The Keystone View Company titled Waiting for Uncle Sam – On the Beach at Porto Rico. The recto depicts a group of naked, mostly dark-skinned children gazing at the horizon. On the verso is printed the following text:

Childhood of whatever nationality is an interesting and amusing study; and on the Porto Rican soil, where all tropical verdure thrives with great luxuriance under the sun’s warm rays, the colored children flourish and multiply without much attention and care and are seen swarming about in all their native simplicity. Whether scrambling up the trunk of the cocoanut palm for a drink of the liquid from the nut, or playing on the beach where they watch Uncle Sam’s stately ships come to anchor, thronging about the city gates, or playing around the rude cabin doorway, they live the same free, Topsy-like life. But under the new regime, among these little natives are we to look for the future citizens and statesmen of the island, and one of the first duties of the United States will be to establish some sort of a system of compulsory education that shall raise the people from their current state of woeful ignorance and provide better things for the coming generation.

Since its inception The Museum of the Old Colony has been shown in various galleries and museums nationally, internationally, and in Puerto Rico, but I always wanted to bring it to Hartford, given the city’s large Puerto Rican population and the complex circumstances that drove Puerto Rican migration to Connecticut. In June 2021, with the support of CICD/ Puerto Rican Parade Committee and the Center for Caribbean Studies at Trinity College, the project, in the form of an outdoor banner produced originally for New York’s Photoville Festival, was installed in Pope Park, just a few minutes’ drive from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Hartford home.

The Museum of the Old Colony: An Art Installation by Pablo Delano, outdoor banner version produced by Photoville Festival, New York City in 2020, exhibited in Pope Park, Hartford, CT in 2021. photo: Pablo Delano

____

Pablo Delano is a visual artist born and raised in Puerto Rico. He is the author of three photographic monographs. His artwork is the subject of a 2022 book from University of Virginia Press, The Museum of the Old Colony: An Art Installation by Pablo Delano, edited by Laura Katzman. Delano serves as the Charles A. Dana Professor of Fine Arts at Trinity College in Hartford. Learn more at http://www.pablodelano.com/.