By Melissa Houston

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2023

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 2018 Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center offered the play Sisters as a public performance and a school program. The public was able to participate in talkbacks after the play with the actors and one of the playwrights. Students participating in the full-day program saw the primary sources that inspired the playwrights, engaged in discussion about how the events represented in the play have been interpreted differently across decades, and reflected on how the play influenced their thinking about race, gender, privilege, and opportunity for women in the 19th century.

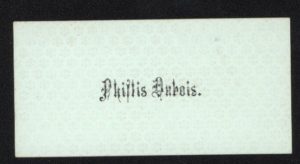

Phillis Dubois and an unidentified child in Ridgefield. No photo of Anna Marie Resseguie has been found to date. photo: Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center.

The main characters are two women—one Black and one white—who lived at the site of Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center through the 19th century. Phillis DuBois came as an eight-year-old freed Black child to the Resseguie household to watch over the family’s white child, Anna Marie, and work in the tavern. The girls grew up in the same household, never married, ran the family’s business, grew old together, and are buried side by side in Ridgefield. The play, co-authored by a Black playwright and a white playwright, portrays how the events on the eve of the Civil War are seen through each woman’s eyes – and calls into question the assumption that they were raised as equals, as “sisters.”

The play Sisters is not just an expression of one museum’s assumptions about race and gender in the 19th century, but rather it uses one museum’s story to challenge every audience member’s understanding of the effects of racial hierarchies on how history is experienced, how lives are lived. The play shines a light on how two women, spending their whole lives together in one house, could have radically different experiences based on the color of their skin. While an over-simplified history about Connecticut’s role in slavery and emancipation often gets shared in our classrooms and museums, the truth is that generations of a culture of oppression and racism brought us to where we are today. It wasn’t simply white Southern men on plantations that knit slavery into the fabric of America, but also white Northern women in small communities like Ridgefield. This legacy should not be brushed over because it informs us about the root causes of discrimination and racism today.

As far as historical records can determine, Phillis Dubois was brought to Ridgefield at age eight by Abijah Resseguie and his wife, Anna Keeler Resseguie, to help run their hotel and care for their child, Anna Marie. Some early 20th-century historians say Phillis’s freedom was purchased by her mother, though her mother remained enslaved in New York. Nathalie Dana, a New York socialite who summered at the Resseguie Hotel, published her memoir Young in New York: A Memoir of a Victorian Girlhood in 1962. She claimed that Phillis was “a slave who refused her freedom when it was offered to her.” The museum has yet to find documentation for either case. Phillis’s early life is largely unknown and perhaps unknowable, given the lack of records documenting Black history in general.

But the story of why Anna Keeler Resseguie would bring Phillis to Ridgefield and what Phillis’s life in the household would be was shaped by generations of women who were involved in holding enslaved women and children captive. To have a better understanding of why Phillis was not and could not be a sister to Anna Marie, we need to step back to the 18th century and look at the lives of Anna Marie’s grandmothers. Traditions and family practices, whether good or bad, are passed down from generation to generation. When Anna and Abijah brought an eight-year-old Black girl into the household to help with the work of running the hotel and caring for their child, we within the framework of their family’s history. The expectation was not that they were adopting Phillis Dubois, but that they were gaining a laborer. While we do not have any documents or history in Anna’s voice, we do know the larger trends in race relations and gender expectations as well as the family’s history.

In October 1723 the Colony of Connecticut passed “An Act for Preventing the Sales of the Real Estates of Heiresses without their Consent,” which is important for understanding Phillis’s story because women on both the Keeler and Resseguie sides of Anna Marie’s family enslaved people. Previously, a woman’s property to her husband’s ownership when they married. This act allowed all inherited property to remain the women’s right to sell, though her husband could improve it or use it while they were married. Traditionally, land was bequeathed to male relatives, but what was termed “moveable property,” things like clothing or furniture, and of lesser value was bequeathed to females. Enslaved individuals were more valuable than most moveable property and leaving enslaved Black people to daughters and wives was a way of securing their financial future regardless of .

Esther Kellogg, one of Anna Marie’s grandmothers, inherited property from her mother’s estate and her grandfather’s estate after the death of her father Samuel Kellogg in 1754. At his death, Samuel had two enslaved men named Jonas and Nimrod, who were bequeathed to Esther’s mother, Ann, who in turn bequeathed all the property she inherited from her late husband, Samuel, to their seven daughters when she remarried later in life. Esther grew up in a household where enslaved Black men worked for the financial benefit of the family, where Black people were understood as property to be inherited, not as equal human beings with rights of their own.

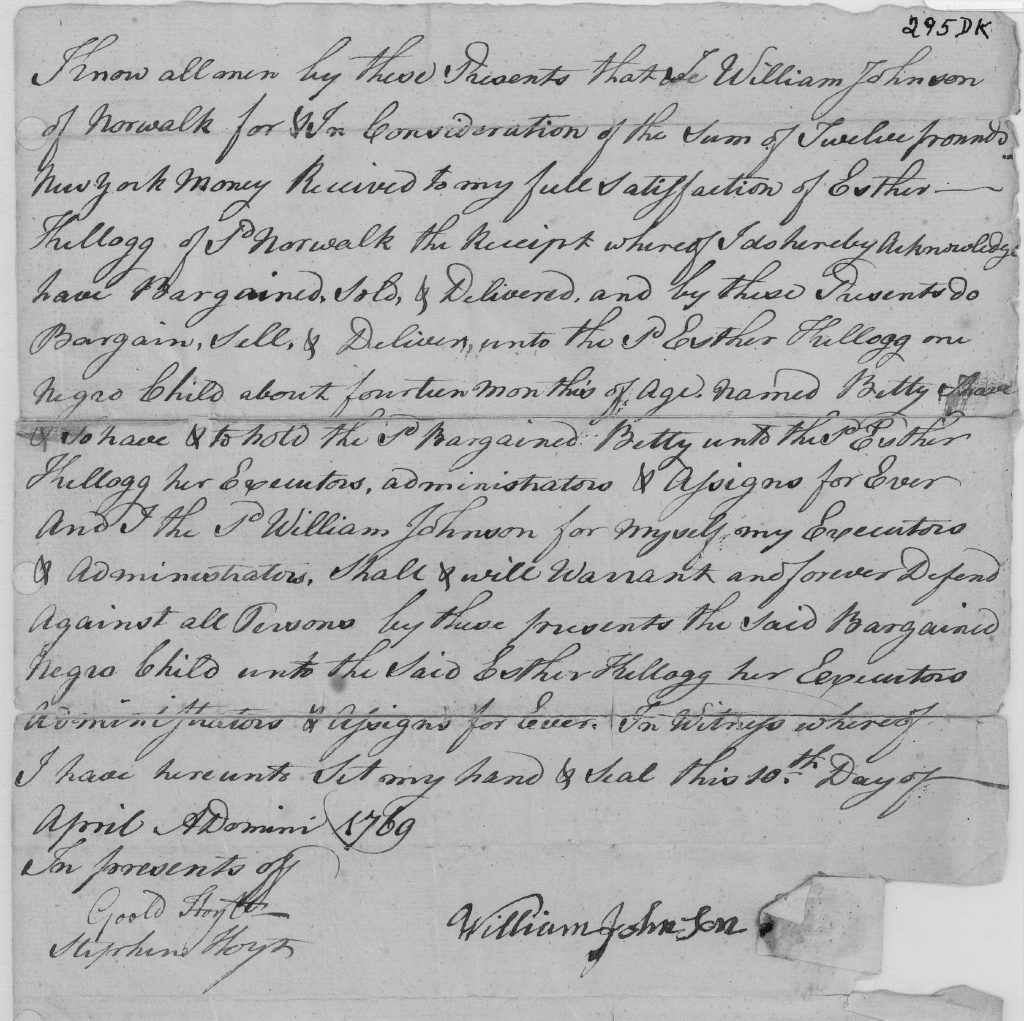

One of the surviving records of Esther’s history, and the history of enslavement in Ridgefield, is a document in the collection of the Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center from 1769. This document is a receipt of sale for Betty Isaac, a 14-month-old child who was sold to Esther Kellogg. Shocking as the sale of a child this age may be, it was established practice to purchase enslaved children, train them in a particular trade or business, and then sell them at a profit. It was also understood that enslaved children could be trained to assist in household tasks and childcare. Esther most likely purchased Betty, having been raised in a household where slavery was practiced, for these reasons. She would have had independent wealth from the property she inherited and the economic agency to make this type of decision.

Anna’s grandfather Timothy also came from a tradition of female enslavers. . Other records in Ridgefield indicate that across her lifetime, Sarah Keeler owned at least six people. In 1780 Timothy’s uncle, Jeremiah Keeler, bequeathed to his wife a “Negro wench named Ellen.” term “wench” was a term used to describe an enslaved woman of childbearing years. White women kept Black women and children enslaved to work in their households. The Keeler women would have raised their children to understand that the enslaved children were not their equals; they were forced labor intended to benefit the white family. The tradition of dehumanizing Black people would have been taught not just through spoken words but also through the way they were treated day to day.

The practice of slavery in smaller New England towns was characterized by white people’s owning only one to two enslaved Black people, which afforded little opportunity for the development of Black families, communities, and even relationships. Though there were a few free Black farming families in the far corners of Ridgefield, they would not have had opportunities to socialize and create relationships with the enslaved Black people who lived along Main Street, owned by the prominent business families and church leaders. According to research by Ridgefield historian Jack Sanders, there were approximately 33 enslaved Black individuals and 25 free or freed Black individuals in Ridgefield between 1708 and 1800. Being Black in Ridgefield was to experience isolation and a lack of community.

In 1723, the same year that women like Esther were enabled to own enslaved Black people, the Colony of Connecticut passed “An Act to Prevent the Disorder of Negro and Indian Servants and Slaves,” which set a 9:00 p.m. curfew for all Black and Indigenous inhabitants in Connecticut. While the Colony would pass acts to restrict the slave trade in the 1770s, slavery was not fully outlawed in Connecticut until 1848. In 1793 the first federal Fugitive Slave Law was passed, authorizing local governments to capture and return enslaved individuals. It was reenforced in 1850 with an updated federal Fugitive Slave Law that made it illegal to assist enslaved people trying to achieve freedom by escaping north. These laws reenforced a national understanding of enslaved Black people as property and as less than human and made for discrimination against all Black people based on the color of their skin.

Anna Marie’s mother, Anna Keeler, was Esther and Timothy’s daughter. She had already grown up understanding Black women as household forced labor. Anna was 42 years old when she married Abijah, and together they had only one child, Anna Marie. Abijah Resseguie grew up in a household where slavery was practiced. His grandfather listed a “negro wench and child” in his inventory. Both the Resseguies and the Keelers were well established and extensive families in Ridgefield’s early history. While not all of the family members engaged directly in slavery, the families would have shared a similar opinion on race, given that both had participated in dehumanizing people based on the color of their skin and treating them as property rather than people.

Phillis lived in Ridgefield under this discrimination and racial tension and came to the Resseguie Hotel with the expectation of being household labor. Some of the most important documents in the museum’s collection for understanding the relationship between Phillis and the Resseguie family are Anna Marie’s diaries from 1851 to 1861, which make nearly 60 references to Phillis. Most describe her housekeeping and cooking for guests and relatives or her prolonged illness. It’s telling that she is so rarely mentioned, and never in endearing ways. Anna Marie records in her diary that she “commenced greatly to my satisfaction a new system with Phillis. Commence giving her wages” on March 7, 1859. Phillis was about 36 years old. Without the financial ability to travel, living in an area with an enforced curfew, lacking a Black community, Phillis would have been isolated and financially oppressed. Technically, since slavery was made illegal in Connecticut in 1848, Phillis could have sued for wages a decade before Anna Marie had the “satisfaction” of deciding to pay her. Phillis was held captive in the Resseguie household, as were Lydia, Betty, and other enslaved Black women held by previous generations.

The final scene of the play Sisters shows Phillis delivering an imaginary conversation with her mother, who is enslaved a state away, about how she came to be in this new household caring for a white baby The monologue ends with her greeting the baby, “Hey Anna Marie. I’m Phillis. Hi. I’m gonna be your big sister and we gonna love each other and we gonna be sisters and have all kinds of stories to tell our children and they gonna tell their children. We gonna have so much fun and we gonna love each other for ever and ever.”

Calling card for Philis Dubois, who was known in Ridgefield for her cooking skills and had a catering business on the side. photo: Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center.

For decades Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center taught the story of Phillis and Anna Marie, one Black woman and one white woman living their lives together in the house through the 19th century, as a story of sisters. The truth is much more complicated than that safe, simple story, and the play digs into how the experiences of these two women would have differed based on the color of their skin. The play challenges audiences to consider how living together and growing up together does not necessarily mean being family or even understanding one another. There are legacies and family

traditions built over generations that inform how we engage with each other and how we engage with history. Acknowledging these legacies will enable museums, and individuals, to face the truth of history and understand a more complete vision of our shared story.

___________