by Carolyn Ivanoff

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The War of 1812 was fought over an enormous area, from Canada and the Great Lakes to the mouth of the Mississippi and along thousands of miles of Atlantic and Gulf coastline. Two Connecticans from Derby, uncle and nephew, had starring roles— one in defeat and one in victory.

Upon declaring war in June 1812, the U.S. was bent on conquering Canada, and Connecticut’s General William Hull was one of the generals in charge. He was born in Derby along the banks of the Housatonic River in 1753, entered Yale at 15, and studied theology for a year. He then changed his course of studies, entering the celebrated law school in Litchfield and gaining admission to the bar in 1775. Hull served with distinction in the American Revolution; in 1812 he was appointed brigadier general and given the charge of capturing Upper Canada from the British.

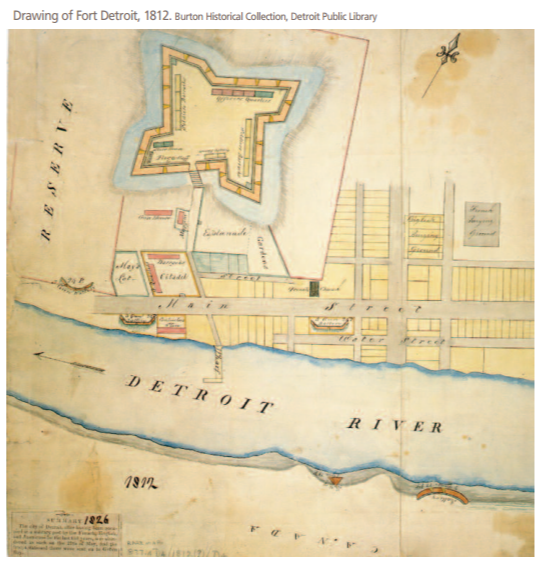

Starting from Ohio Territory that June, General Hull advanced on Detroit by cutting a new road, a task that took most of the month. He arrived at Fort Detroit on July 5. Fort Detroit covered two acres in a vast wilderness and housed about 800 people. On July 29 the U.S. fort at Mackinac was captured by British and Native American forces and Hull’s new road was overrun. Cut off from support and reinforcements, Hull feared massacre. General Henry Dearborn, who had planned the overall three-pronged strategy to seize Canada, was ordered by the secretary of war to proceed to Albany for an invasion at Niagara. As Hull foundered, Dearborn failed to take any aggressive action

Starting from Ohio Territory that June, General Hull advanced on Detroit by cutting a new road, a task that took most of the month. He arrived at Fort Detroit on July 5. Fort Detroit covered two acres in a vast wilderness and housed about 800 people. On July 29 the U.S. fort at Mackinac was captured by British and Native American forces and Hull’s new road was overrun. Cut off from support and reinforcements, Hull feared massacre. General Henry Dearborn, who had planned the overall three-pronged strategy to seize Canada, was ordered by the secretary of war to proceed to Albany for an invasion at Niagara. As Hull foundered, Dearborn failed to take any aggressive action

Hull had suffered a stroke the preceding year, and his difficulty controlling his horse—and his quarreling officers—made him appear cowardly. He put off the attack his officers demanded and sent detachments to reopen the road for reinforcements but was beaten back by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. British forces and their Native-American allies crossed the Detroit River and prepared to lay siege, issuing an ultimatum that included the threat of massacre. Hull’s behavior became more bizarre. His speech became indistinct; he dribbled tobacco juice incessantly and took to crouching in corners of the fort. Hull surrendered, without consulting his officers, on August 16; his men were outraged. Hull later claimed to be short of ammunition, but he was courtmartialed and tried for cowardice in the line of duty. The court-martial was headed by General Dearborn, who had failed to come to Hull’s aid. Hull was condemned to death. President Madison would later commute the sentence, but the defeat at Detroit had shocked the nation and opened the entire Northwest frontier to attack by the British and their Native-American allies. The nation desperately needed good news after this stunning defeat in the Northwest. It would be Hull’s nephew Isaac who redeemed America’s honor, and the Hull name, with an equally stunning victory at sea.

Isaac Hull was born in Derby in 1773, the second of seven sons. His father Joseph, William Hull’s brother, had fought in the Revolutionary War, leading a flotilla of whaleboats against the British on Long Island Sound. The sea was in young Isaac’s blood. At age 14 he went to sea as a cabin boy; at 19 he commanded his own ship. In 1798 he was commissioned a fourth lieutenant and assigned to the USS Constitution to fight the Quasi-War (1798-1800) with France and the Barbary pirates of North Africa. Ultimately Hull would command the Constitution.

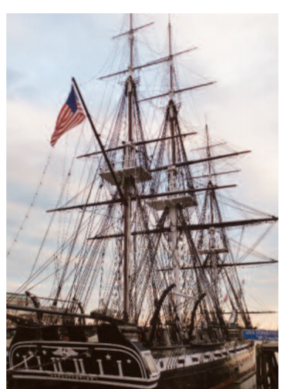

The Constitution was one of three 44- gun war frigates in the U.S. Navy. Designed by Joshua Humphreys, she represented the cutting edge of sailing and combat technology. Launched from Boston in 1797, constructed of live oak, red cedar, and hard pine, she was 204 feet long with a beam of 43 feet, and she weighed 2,200 tons. The copper sheath on her hull was crafted by Paul Revere. She carried 44 cannon, with ranges up to 1,200 yards, and a crew of 450 sailors. Seventy-two sails covered three masts, and her main mast rose 233 feet. Her speed could reach 12 knots in a good wind. She was painted black and white and cost $302,718. She is forever immortalized as “Old Ironsides,” dubbed so under the command of Isaac Hull.

In 1812 on the high seas the fledgling United States challenged Britannia’s rule of the waves with 17 oceangoing ships against 700 of the greatest navy in the world. The U.S. Navy had the formidable task of defending nearly two thousand miles of U.S. coastline. In June 1812, Isaac Hull, with the rank of captain, assumed command of the Constitution. Hull’s crewmen were new recruits inexperienced at working on a large ship. He trained and drilled them thoroughly before departure. The Constitution stopped at Annapolis to take on stores, and Hull joined his ship as she sailed down the Chesapeake Bay. On July 12, 1812, she turned north to travel up the east coast.

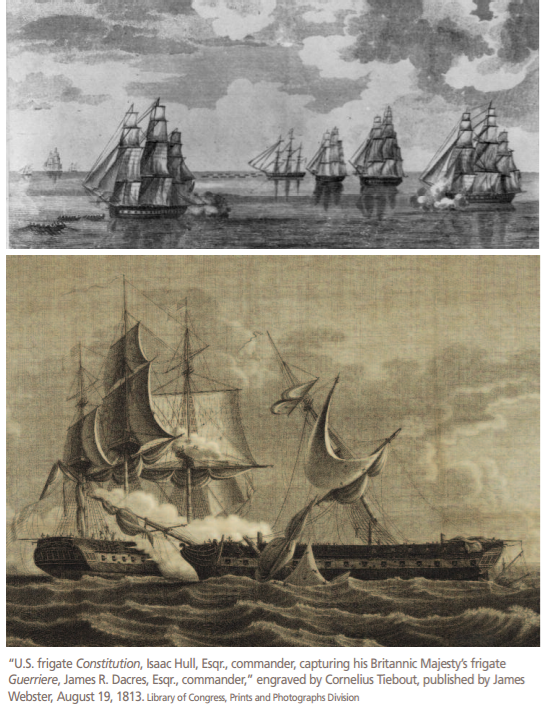

On July 16 The Constitution’s lookout spotted several sails on the horizon. By 5 the next morning, five British warships were closing in on Constitution. Hull knew it was suicidal to fight all five. His best strategy was to out-sail them. So began what may have been the greatest chase in naval history

Hull ordered portholes in his rear cabin knocked out and widened and had two 24-pound cannon placed in the openings. He ordered a long 18-pounder placed on the Constitution’s spar-deck as a stern-chaser and another pointed off the forecastle. Then the wind died and the Constitution was dead in the water, with the enemy less than 12 miles away.

Hull ordered his cutters (small boats) lowered, lines attached, and his men to row with all their might, pulling the Constitution forward. The British followed suit—but with more cutters. They quickly gained on the Constitution.

Hull then ordered his men to start “kedging,” a method frequently used on the Housatonic River and one that Hull knew well. Sailors rowed a 700-pound kedge, or anchor, far in front of the ship. The sailors turned the ship’s capstan to haul the ship toward the anchor. Another cutter repeated this maneuver with the second 400-pound kedge. With the British closing in, the Constitution opened fire from her stern. The British ships backed off and concentrated all their rowers on two ships. The HMS Belvidera was within firing distance, and her bow cannon blazed. The American crew shouted defiantly as shots fell short of the Constitution’s stern. The Constitution’s rear cannon answered, and a cannonball smashed into Belvidera’s main deck. The HMS Guerriere opened fire, but her shots fell short of the Constitution.

Hull then ordered his men to start “kedging,” a method frequently used on the Housatonic River and one that Hull knew well. Sailors rowed a 700-pound kedge, or anchor, far in front of the ship. The sailors turned the ship’s capstan to haul the ship toward the anchor. Another cutter repeated this maneuver with the second 400-pound kedge. With the British closing in, the Constitution opened fire from her stern. The British ships backed off and concentrated all their rowers on two ships. The HMS Belvidera was within firing distance, and her bow cannon blazed. The American crew shouted defiantly as shots fell short of the Constitution’s stern. The Constitution’s rear cannon answered, and a cannonball smashed into Belvidera’s main deck. The HMS Guerriere opened fire, but her shots fell short of the Constitution.

For two days and nights the chase ground on, suspended only when a slight wind came up. Hull ordered buckets of water hoisted to wet the sails, making them more sensitive to any breeze. As the breeze died again, cutters once more were sent out to pull the Constitution forward, and the exhausting chase continued. Hull ordered 10 tons of drinking water pumped out to lighten the ship. The gap between the Americans and the British widened. Hull stayed at his command post on deck during the entire grueling chase. At dawn on July 19, the Constitution had opened a twomile lead. An hour later the wind came up and the Constitution sped away. The Guerriere and the Aeolus attempted to cut her off, but the Constitution’s speed and Hull’s superior seamanship prevailed. The chase continued into the afternoon, when the British gave up. Hull and his crew had out-sailed a numerically superior British squadron in a 57-hour demonstration of leadership, endurance, and seamanship unparalleled in naval history. The Constitution sailed into Boston, where there had been rumors of her sinking. Hull, his crew, and his ship were hailed as national heroes.

Fearing blockade, Captain Hull anchored long enough to restock supplies and was back at sea by August 2. Over the next two weeks Hull captured three British cargo ships and kept a lookout for the Guerriere, whose Captain James Dacres had publicly bragged his ship would quickly send any American frigate to the bottom of the sea. At 2 in the afternoon of August 19, off the coast of Nova Scotia, the Constitution’s lookouts raised cries of “sail ho!” The Guerriere was in their sights. Captain Dacres reportedly told his crew, “There is the Yankee frigate, in forty-five minutes she is certainly ours. Take her in fifteen and I promise you four months’ pay.” As the Constitution closed with the Guerriere, Dacres fired broadside after broadside, but Hull held his fire. British cannonballs struck the Constitution but bounced harmlessly off her live oak hull and copper sheathing. A crewman is said to have shouted, “Hurrah, her sides are made of iron!” and “Old Ironsides” was born.

USS Constitution, 2012. Visit “Old Ironsides”

at the Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston. photo: Carolyn Ivanoff

With the ships now only 25 With the ships now only 25 yards apart, Dacres tried to pull away when he realized that his ship was vulnerable. According to several accounts, Hull gave the command, “Now boys! Pour it into them!” The first broadside of double shot exploded from every muzzle and raked the Guerriere at close range, with devastating effect. The Constitution fired again and again; then Hull demonstrated his superior seamanship by crossing the Guerriere’s bow, pouring fire from his guns. Several accounts report that short, fat Captain Hull split the seat right out of his breeches amidst the battle action. Another broadside raked the Guerriere and toppled her mizzen-mast. Hull reportedly ignored his split-open pants and shouted above the roar, “Huzza, my boys! We’ve made a brig of her!”

The destroyed mizzen-mast slowed the Guerriere, and as the Constitution attempted to cross her bow again, the ships entangled. Constitution poured another broadside into the Guerriere’s bow, and the Guerriere’s guns set Hull’s cabin on fire. Trumpeters on both ships called for boarding parties. Marine marksmen in both ships’ riggings added deadly sniper fire to the fight. The Constitution broke loose and prepared to rake the Guerriere again. The wounded Dacres signaled surrender. In a gesture recalling one of the main reasons the U.S. had gone to war, Hull freed 10 impressed American sailors from the Guerriere.

The next day Hull blew up the sinking Guerriere and sailed for Boston to report his victory and land his prisoners. Details of the victory were reported in newspapers, along with the news of his uncle’s defeat. The entire nation went wild with adulation for Isaac Hull, his crew, and the remarkable ship forever to be known as “Old Ironsides.” The national pride and jubilation over Hull’s remarkable victory would obscure, for a little while at least, New England’s hostility toward the unpopular war of which it was part.