By Lizabeth Cohen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. This story is adapted from Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age by Lizabeth Cohen. © 2019 by Lizabeth Cohen. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

NOTE: CTExplored selected the excerpt from Dr. Cohen’s book to place the reader back in a time and place when urban renewal was a new idea. The story’s intent is not to lionize Ed Logue or Richard Lee, far from it. It enables us to look critically at a concept we now understand—in hindsight—to be deeply flawed, a lesson learned at great cost. Please also visit “Preserving Dixwell in New Haven as a Model,” Spring 2013.

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In September 1953, 32-year-old Ed Logue returned to New Haven with his wife Margaret after six years away to await the birth of their first child. Though born and raised in Philadelphia, in New Haven he had widened his horizons as a scholarship student at Yale College, had worked his first full-time job as a labor organizer, and—after a stint in the U.S. Army Airforce during World War II—had trained for a profession at Yale Law School. Here, too, he had met and married Margaret, the daughter of the influential couple in New Haven academic circles, the much-admired dean of Yale College William Clyde DeVane and his wife, Mabel Phillips DeVane.

After serving as one-term Democratic Connecticut Governor Chester Bowles’s labor secretary, Logue followed him when President Harry Truman appointed Bowles as ambassador to India and Nepal. Casting about for his next career move after working in India for 18 months, Logue was considering hanging out his shingle as a New Haven lawyer.

Logue arrived just in time to help with the third mayoral campaign of the Democratic reform candidate Richard Lee, then director of the Yale News Bureau. “Dick” Lee, the determined, 37-year-old hometown boy who had served 14 years as a city alderman representing his home district, the Irish Democratic Seventeenth Ward, built his latest run around an ambitious promise to renew what was undeniably a deteriorating New Haven. Factories were closing, downtown retail was stagnating, and middle-class residents were decamping for the city’s flourishing suburbs. These departures, in addition to continued loss of property tax revenue due to Yale’s ever-expanding footprint, were fueling growing discontent among those remaining behind, who resented how the city’s property tax rates kept climbing simply to sustain existing services. Logue became a key player in Independents for Lee, an effort to position Lee as an alternative to business as usual as practiced by New Haven’s Democratic Party machine. The third time was the charm, and Lee claimed victory on November 3, 1953, with 52.3 percent of the vote.

Big Ideas and Big Plans

Within weeks of his election, Lee invited Logue to be his executive secretary, an ostensibly part-time post that Lee created to tap the unique combination of smarts, energy, and vision that he saw in Logue. Logue accepted, but it quickly became apparent that the job was much bigger, more like an unofficial deputy mayor. They lost little time collaborating on an ambitious plan to remake New Haven as a “slumless city—the first in the nation,” as they liked to say.

In February 1955 Lee officially appointed Logue as the development administrator of the New Haven Redevelopment Agency. Logue would prove to be brilliant at garnering newly available federal urban renewal funds. With Lee’s intimate knowledge of New Haven, the pair became an irrepressible and nationally admired team who could boast that they were attracting more federal dollars per capita to New Haven than any other American city was getting. They shared the conviction that rebuilding a city physically was a necessary part of revitalizing its economy and offering greater opportunities to its residents.

Logue and Lee’s ability to use federal funding for New Haven’s urban renewal was made possible by the federal housing acts of 1937, 1949, and 1954 and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. It came naturally to Logue and Lee, as committed New Deal Democrats, to turn to the federal government to foot the bill for much of New Haven’s redevelopment. During Lee’s years in office, New Haven would attract more than $130 million in federal aid (more than $1 billion in today’s dollars), which in 1965 put it sixth among the 12 cities receiving the largest federal renewal grants and easily ranked it first in grant money per capita.

Lee and Logue were able to move so quickly because they could easily meet the federal government’s requirement that a general redevelopment plan be made and approved before funds would be authorized. Lee had campaigned on the idea. Lee and Logue had a plan that was pragmatic, comprehensive, and “focus[ed]on the city as a whole and treat[ed]all urban problems as interrelated,” Logue wrote in an article for The New York Times November 9, 1958.

The plan originally had been created by planner Maurice Rotival—Logue’s former professor at Yale—in 1941. A version had been distributed publicly in 1944 as a 34-page pamphlet titled Tomorrow is Here and then had been updated by Rotival several times. A French-born planner and engineer heavily influenced by the sensibilities of Le Corbusier, Rotival applied to his plan a basic principle that the modern city must be oriented around the car and to its historic role as a distribution center. Now the highway would serve as the lifeblood of the city’s future development as a trade and service center for the entire southern New England region.

Frustrated with New Haven politics—a weak mayor facing reelection every two years, an unwieldy board of 33 elected alderman, and an equally unwieldy array of boards and commissions—Lee (who served as mayor for 16 years) set up Logue in early 1955 as an independent, powerful development administrator reporting directly to the mayor and insulated from New Haven’s calcified politics as usual by the enormous amount of federal money underwriting urban renewal. He gave Logue official oversight of all city departments concerned with physical development, which long had operated independently or antagonistically toward one another. These included the New Haven Redevelopment Agency, the City Plan Department, the Housing Authority, the Building Inspector, Traffic and Parking, and relevant aspects of the Health Department.

Lee and Logue inherited a city laid out in the 18th and early 19th centuries with narrow streets for horses and carriages, later adapted to electric streetcars. New Haven had only recently given up its trolleys, the last city in Connecticut to do so, according to Robert Leeney in Elms, Arms, and Ivy: New Haven in the Twentieth Century (New Haven Museum, 2000). Lee and Logue called for wider, straighter, faster-moving main streets; abundant—preferably off-street—parking; and secondary streets dead-ended to discourage through-traffic.

Adjusting New Haven to the automobile shaped new residential projects as well, as the urban renewers tried to compete with the draw of the suburbs. New luxury apartment towers close to downtown were publicized as “town living in the modern manner,” which meant plenty of parking on the landscaped grounds. Modernist architect John Johansen designed the Florence Virtue Homes in the African American neighborhood of Dixwell as a modernist, concrete-block, garden apartment-type complex with buildings occupying only 16 percent of its landscaped site. Front and back yards for each townhouse, curvy roads, and off-street parking contributed to a suburban feel. The adjacent Dixwell Plaza extended the anti-urban, village-like concept with a new K – 4 school topped by a bell tower, a church, a library, and a community center. A shopping arcade that resembled a suburban-strip shopping center with parking was intended to serve as the new commercial heart of the neighborhood.

Whenever Lee and Logue strategized about how best to thwart the suburban threat to New Haven, they fixed on the importance of improving city schools, which long had been underfunded, overcrowded, racially segregated, and physically deteriorating. An exodus from the city’s public schools had resulted. By 1964 one child out of four in New Haven attended private school. Meanwhile, the suburbs were spending extravagantly on their schools. Logue and Lee responded by launching a New Schools for New Haven initiative and constructed 12 new schools. They used the new schools to innovate socially—intending to serve neighborhood residents during both day and evening. One “community school” included a senior citizens’ center, a branch library, meeting rooms, and a swimming pool. But to their frustration, their ambition to integrate the city’s schools met stiff opposition from many white residents.

The Church Street Project

Before the 1940s New Haven had faced little commercial competition from the surrounding area. But times were changing: the Gamble-Desmond department store shut its doors in 1953, and Sears Roebuck followed in 1956. Shopping centers popped up one after another in the suburbs surrounding the city. In the first year after the 29-store Hamden Plaza shopping center opened in 1955, it did $33 million in sales, most of it diverted from New Haven stores, notes Jeff Hardwick in “A Downtown Utopia?” (Planning History Studies, vol. 10, 1996). But what really set off alarm bells was learning from a Louis Harris survey Logue secretly commissioned in 1956 that city residents were increasingly patronizing the new suburban shopping centers as well. They cited congested streets, inadequate parking, and old-fashioned stores as their reasons for heading out of town to shop.

Before the 1940s New Haven had faced little commercial competition from the surrounding area. But times were changing: the Gamble-Desmond department store shut its doors in 1953, and Sears Roebuck followed in 1956. Shopping centers popped up one after another in the suburbs surrounding the city. In the first year after the 29-store Hamden Plaza shopping center opened in 1955, it did $33 million in sales, most of it diverted from New Haven stores, notes Jeff Hardwick in “A Downtown Utopia?” (Planning History Studies, vol. 10, 1996). But what really set off alarm bells was learning from a Louis Harris survey Logue secretly commissioned in 1956 that city residents were increasingly patronizing the new suburban shopping centers as well. They cited congested streets, inadequate parking, and old-fashioned stores as their reasons for heading out of town to shop.

Lee and Logue hatched plans to demolish the three-square blocks at the heart of downtown and replace them with the Church Street Project, consisting of new Malley’s and Macy’s department stores, the Chapel Square Mall with smaller specialty shops, and a huge attached parking garage. In many ways it was an effort to beat the suburbs at their own game, to build a bigger, better “regional shopping center in the heart of the city,” as Logue’s office put it. The Redevelopment Agency carefully studied suburban shopping centers for models. The goal was to introduce features that made shopping in the city as comfortable—and safe—as shopping in the suburbs, particularly for women.

Prospective retail tenants confirmed that access to parking and the highway connector mattered significantly in their decisions. Malley’s chose to move from its historic home facing the New Haven Green to a new location closer to the connector and new massive Temple Street parking garage. Macy’s made it clear that it would use New Haven as a foothold for its planned expansion into the New England market only if its store enjoyed proximity to highways and parking. Soon after the garage was completed in 1963 Macy’s officials congratulated Mayor Lee and acknowledged “the chief reason we are coming to New Haven is to tie into that structure.” They also lauded the “spur connect[ing]the Connecticut Turnpike to the downtown section of New Haven” and “the ramps which lead directly to Macy’s parking facilities.”

Creating Long Wharf

Rotival’s plan for New Haven introduced Lee and Logue to several other modernist principles. Among the most fundamental was the concept of separation of functions. As Rotival put it in Tomorrow is Here, “Each section of the city would be defined so that housing will not interfere with industry, nor industry with the market, nor transportation with parks and playgrounds. Yet all are tied together so that each section operates efficiently.” With this in mind, Lee and Logue targeted areas of mixed use for renewal activity—neighborhoods like Oak Street, Wooster Square, and Dixwell where sweatshops and machine shops were often cheek by jowl with grocery stores or rows of tenement flats. Lee and Logue determined to separate uses, convinced that their proximity contributed to disorderly, run-down residential areas and overlooking how that mix might have kept them affordable—and accessible to residents.

The principle of separating uses guided the relocation of the proposed north-south Route 91 so that it divided Wooster Square into a more purely residential quarter and an industrial district, which then was expanded to include a new 350-acre area named Long Wharf, built on reclaimed land along the harbor. Long Wharf housed a new wholesale food distribution center, a modern reinvention of the outdoor street market that planners relocated from downtown. Logue hoped that by consolidating industry and wholesale commerce at Long Wharf—convenient to I-95 and rail and water transport—the city’s new industrial center would serve as a beacon attracting further investment and jobs back to the city. It was considered a great victory when the Armstrong Rubber Company, Gant Shirtmakers, and C. W. Blakeslee, a long-time manufacturer of pre-stressed concrete, all opened substantial new factories there.

Mayor Richard Lee shakes President Lyndon Johnson’s hand at the signing of the Housing and Urban Development Act, 1965.

New Haven Museum

Modern Design

Another major goal of Lee and Logue’s physical renewal of New Haven came from their own inclinations. They decided that constructing architecturally modern buildings would send just the right message that New Haven was reinventing itself. Further, they hoped that showcasing the work of prominent architects would lend prestige to New Haven’s rebirth, particularly when combined with what was happening on Yale’s campus, where no fewer than 26 buildings designed by, as Time magazine noted (November 15, 1963), “the most lustrous and far-out contemporary master builders,” who “adhered to no single style, only to the modern mood,” were erected between 1951 and 1963. Indeed, the architects who would work in New Haven constituted a who’s who of modernist designers. [See “Modernism in Connecticut”.]

But several initial projects—the new Southern New England Telephone headquarters (which Architectural Forum panned as “that great green hulk … which looks like it was designed by the janitor,”) and the first two apartment towers on Oak Street—failed to meet expectations. Logue then hired Paul Rudolph, newly appointed chair of the department of architecture at Yale, as design consultant. In Rudolph, he felt he had found “a man of such outstanding reputation that the question of our competence could not be raised again,” as he wrote in a letter to Roger Stevens, developer of the Church Street Project.

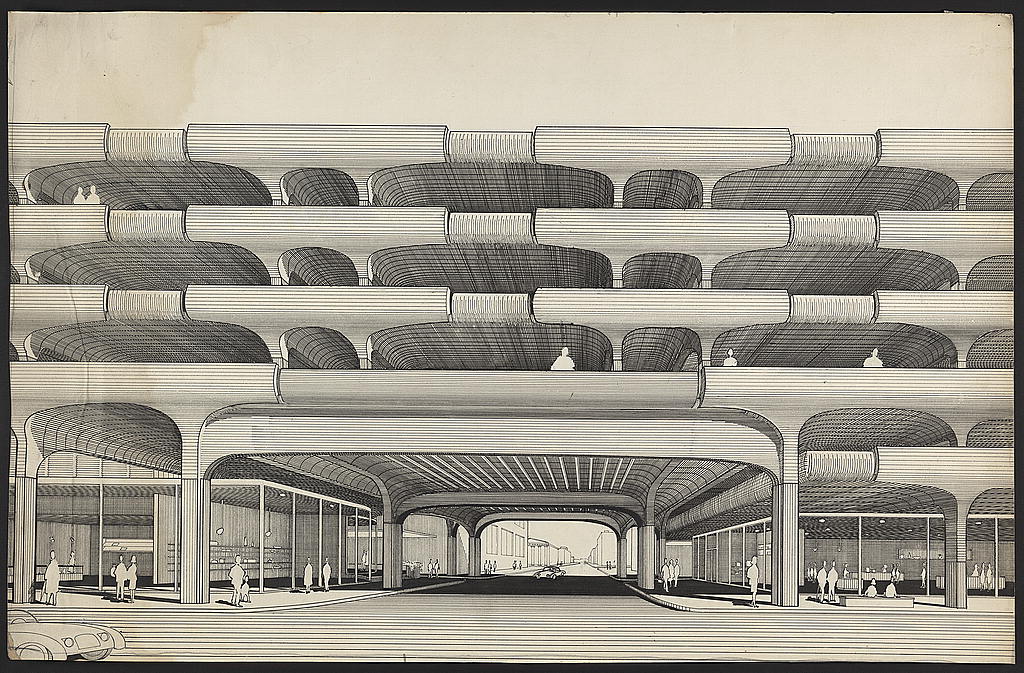

As design consultant to the Church Street Project, Rudolph had some influence on the final design. The greatest prize he walked away with, however, was the commission to design the two-block-long, 1,300-car Temple Street Parking Garage, which has probably become his best-known urban renewal project. Architectural Forum praised the Temple Street garage in its pages as “an enormous, unabashed piece of sculpture.”

Lee and Logue also strove for an élan of monumentality. City centers “lack the magic appeal of the western European cities,” Logue lamented in a May 1967 statement to the National Commission on Urban Problems. Superblocks—merging small parcels into larger parcels conducive to big projects—provided one common tool to break out of what many urban planners of the time considered the confining grid of the 19th-century city and introduce more light, air, and grand scale. Critics would later—and often rightly—condemn superblocks for decreasing density and creating vacant and alienating urban space.

Logue wanted to create a monumental space as part of the Church Street Project’s Chapel Square Mall and sought a setback at the corner of Church and Chapel streets for a pedestrian promenade and fountains. When Stevens resisted, saying he couldn’t afford to reduce rentable space, they compromised. The city decided to consider open spaces as a non-income-producing public use, relieving Stevens of taxes and maintenance for them.

Model Modern City

In 1966 WNBC-TV broadcast Connecticut Illustrated: A City Reborn, a documentary celebrating the city’s transformation over the previous 10 years from one “choked with slums into a model modern city.” Awards mounted. Lee and Logue were proud that their achievements were being acknowledged. The very next year, however, New Haven residents unhappy with urban renewal’s impact would go very public with their opposition. But by then Logue was long gone from New Haven. After seven years there, a now nationally-known Logue had been lured to Boston in 1961 to head the newly strengthened Boston Redevelopment Authority. During his seven years in Boston, Logue received credit for orchestrating the city’s turnaround. He also learned to preserve more of the city’s historic fabric and to negotiate better with neighborhood groups. In 1968 New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller recruited Logue to head his own pioneering statewide urban renewal agency, the New York State Urban Development Corporation. Logue ended his career in the 1980s working to revitalize some of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods in the South Bronx.

What began with idealism and free-flowing federal dollars in New Haven in the 1950s would end decades later with much-diminished public support for cities but also much greater awareness of the need to involve residents in decisions affecting their communities. This is the story that Ed Logue’s long career reveals and that Saving America’s Cities sets out to tell.

Lizabeth Cohen is the Howard Mumford Jones Professor of American Studies in the history department at Harvard University.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO Summer 2021 Contents

“Preserving Dixwell in New Haven as a Model,” Spring 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Print Issue

Subscribe to our bi-weekly e-newletter