(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Fall 2017 All images from The Amistad Center for Art & Culture.

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

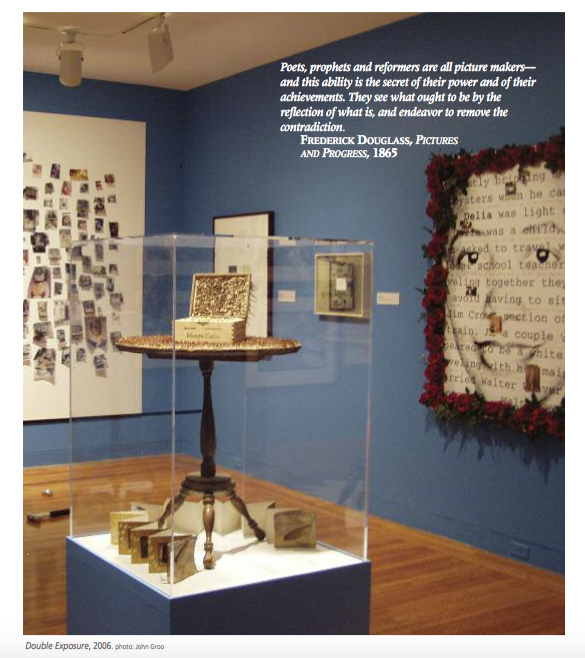

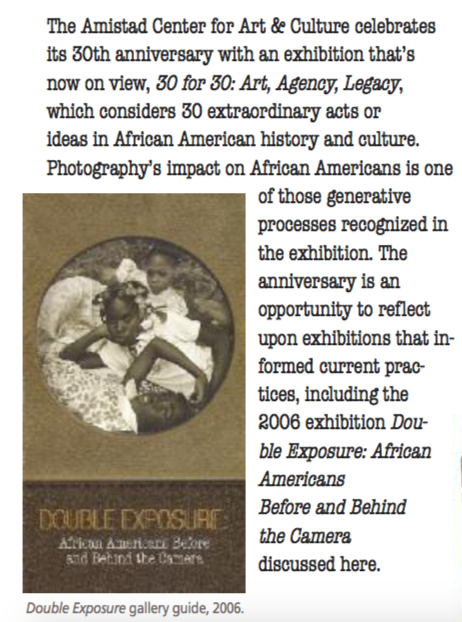

In 2006 The Amistad Center for Art & Culture in Hartford mounted Double Exposure, a major exhibition that paired historic photography from its Simpson Collection with visionary work by 20th-century black photographers. To organize the exhibition, the center assembled an intergenerational team that, as it turns out, would articulate a creative direction and exhibition template for the center’s future.

In 2006 The Amistad Center for Art & Culture in Hartford mounted Double Exposure, a major exhibition that paired historic photography from its Simpson Collection with visionary work by 20th-century black photographers. To organize the exhibition, the center assembled an intergenerational team that, as it turns out, would articulate a creative direction and exhibition template for the center’s future.

Double Exposure had its genesis years before with the friendly conversations between the Amistad Center’s second director and curator Deirdre Bibby and photographer/historian Deborah Willis. A box of images and notes sat waiting in storage for the conversations to continue. The center’s third director, Olivia White, revived the spirit of the idea. With a team that included Deborah Willis, photo researcher Lisa Henry, and center staff, work on Double Exposure began. Supported by several area foundations, Double Exposure opened in Hartford and then toured the country with the support of The Aetna Foundation.

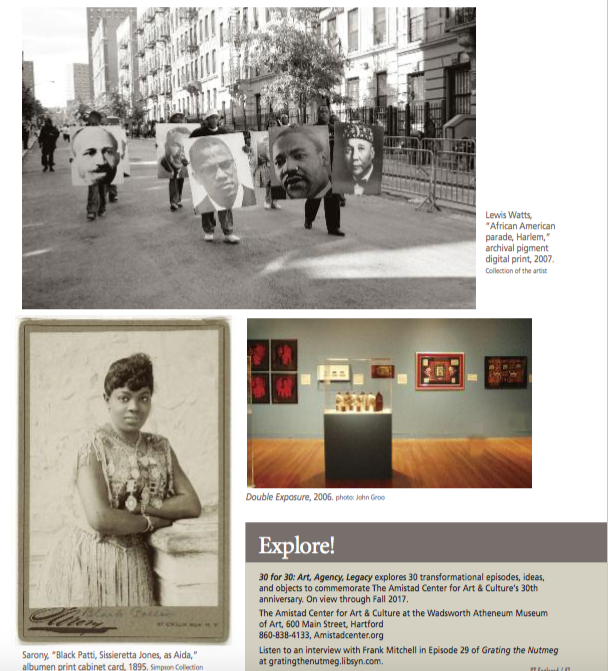

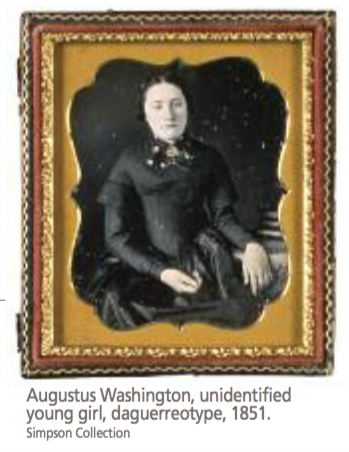

Hartford’s Augustus Washington and other pioneering black photographers imagined the medium’s implications for 19th-century African America. Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and other subjects used the medium in campaigning to end slavery and redefine black humanity. That legacy informs the continuous innovation that defines contemporary photography. For that reason, Washington’s work and images of Douglass and Truth are featured in the current exhibition 30 for 30.

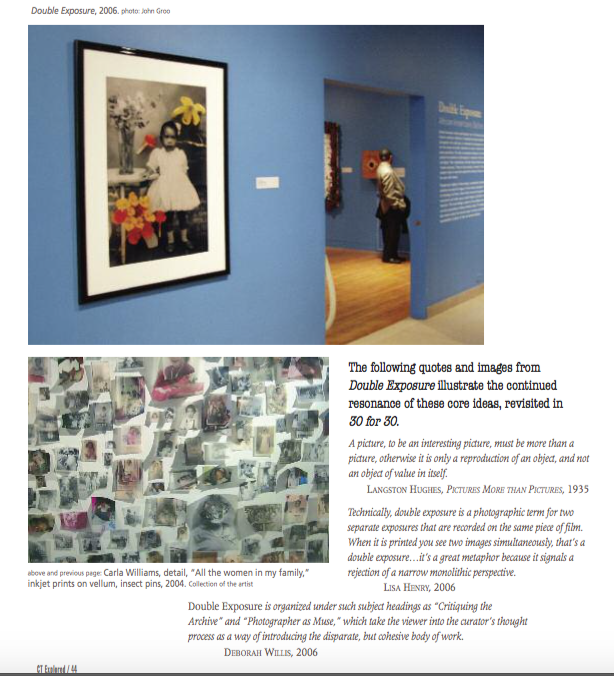

The following quotes and images from Double Exposure illustrate the continued resonance of these core ideas, revisited in 30 for 30.

A picture, to be an interesting picture, must be more than a picture, otherwise it is only a reproduction of an object, and not an object of value in itself.

Langston Hughes, Pictures More than Pictures, 1935

Technically, double exposure is a photographic term for two separate exposures that are recorded on the same piece of film. When it is printed you see two images simultaneously, that’s a double exposure…it’s a great metaphor because it signals a rejection of a narrow monolithic perspective.

Lisa Henry, 2006

Double Exposure is organized under such subject headings as “Critiquing the Archive” and “Photographer as Muse,” which take the viewer into the curator’s thought process as a way of introducing the disparate, but cohesive body of work.

Deborah Willis, 2006

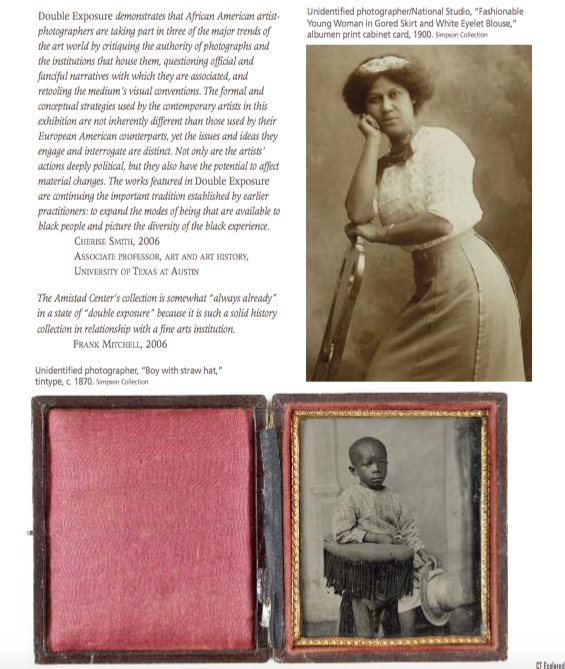

Double Exposure demonstrates that African American artist-photographers are taking part in three of the major trends of the art world by critiquing the authority of photographs and the institutions that house them, questioning official and fanciful narratives with which they are associated, and retooling the medium’s visual conventions. The formal and conceptual strategies used by the contemporary artists in this exhibition are not inherently different than those used by their European American counterparts, yet the issues and ideas they engage and interrogate are distinct. Not only are the artists’ actions deeply political, but they also have the potential to affect material changes. The works featured in Double Exposure are continuing the important tradition established by earlier practitioners: to expand the modes of being that are available to black people and picture the diversity of the black experience.

Cherise Smith, 2006

Associate professor, art and art history

University of Texas at AustinThe Amistad Center’s collection is somewhat “always already” in a state of “double exposure” because it is such a solid history collection in relationship with a fine arts institution.

Frank Mitchell, 2006

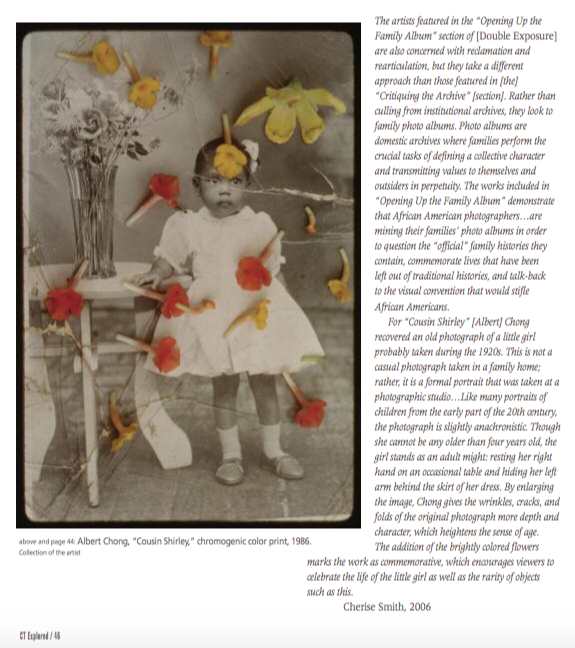

The artists featured in the “Opening Up the Family Album” section of [Double Exposure] are also concerned with reclamation and rearticulation, but they take a different approach than those featured in [the]“Critiquing the Archive” [section]. Rather than culling from institutional archives, they look to family photo albums. Photo albums are domestic archives where families perform the crucial tasks of defining a collective character and transmitting values to themselves and outsiders in perpetuity. The works included in “Opening Up the Family Album” demonstrate that African American photographers…are mining their families’ photo albums in order to question the “official” family histories they contain, commemorate lives that have been left out of traditional histories, and talk-back to the visual convention that would stifle African Americans.

For “Cousin Shirley” [Albert] Chong recovered an old photograph of a little girl probably taken during the 1920s. This is not a casual photograph taken in a family home; rather, it is a formal portrait that was taken at a photographic studio…Like many portraits of children from the early part of the 20th century, the photograph is slightly anachronistic. Though she cannot be any older than four years old, the girl stands as an adult might: resting her right hand on an occasional table and hiding her left arm behind the skirt of her dress. By enlarging the image, Chong gives the wrinkles, cracks, and folds of the original photograph more depth and character, which heightens the sense of age. The addition of the brightly colored flowers marks the work as commemorative, which encourages viewers to celebrate the life of the little girl as well as the rarity of objects such as this.

Cherise Smith, 2006

Double Exposure urged us to see our photography collection in new ways influenced by the definitions of family album, historical archives, and the challenges of representation. The Amistad Center’s collection has work by celebrated contemporary black photographers, noted early black photographers, and portraits of black subjects that history may never claim. Double Exposure was a lesson in the ways artists and curators can assist diverse material in telling a common story while maintaining the unique specificity of each voice.

Wm. Frank Mitchell was executive director of The Amistad Center for Art & Culture. He wrote “A Fortress for Faith-based Advocacy: The Knights of Columbus” Fall 2015.

Explore!

The Amistad Center for Art & Culture at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

600 Main Street, Hartford

860-838-4133, Amistadcenter.org

Listen to an interview with Frank Mitchell in Episode 29 of Grating the Nutmeg at gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com.