By Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser

By Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser

(c) Connecticut Explored, Winter 2004-2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The rise of the Hudson River school in the second quarter of the 19th century has proven to be one of the most important cultural developments in the United States. It reigned as a national school of landscape art until about 1870, and while it has traditionally been identified as beginning with the 1825 arrival of Thomas Cole (1801-1848) in New York City, this native school did not form itself out of thin air, but was, in fact, decades in the making.[1] At the turn of the 18th century, Daniel Wadsworth (1771-1848), founder of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, was one of a handful of enlightened patrons who played critical roles in laying the groundwork for the development of the Hudson River school. By 1844, he had opened the Wadsworth Atheneum to the public where paintings by leading members of the Hudson River school were featured in the galleries.

An amateur artist, architect, and one of the most important patrons of American artists, Wadsworth became a lifelong promoter of his nation’s culture. This interest inspired his collection of contemporary American art that formed the basis for the museum he established. As a member of the first generation of citizens of the new republic, Wadsworth saw his country’s history and vast wilderness as conjoined, symbolic of the nation’s potential greatness, and these two themes defined his vision for the Wadsworth Atheneum.

The son of Colonel Jeremiah Wadsworth (1743-1804), one of Connecticut’s wealthiest and most powerful men, Daniel’s Puritan ancestors were among the original founders of the state, travelers in the party led by Reverend Thomas Hooker that journeyed from Massachusetts Bay Colony to found Hartford in 1636. Members of his family served in the formation of the new nation. In his later life, as a witness to the ensuing rise of Jacksonian democracy, Wadsworth retreated from the political arena favored by his father; he saw a different role for himself-that of helping to establish an American cultural heritage. For Wadsworth and others of his era, the American landscape became the focus of aesthetic inquiry. Landscape was seen as a morally uplifting influence on the country’s inhabitants.

Wadsworth was first exposed to the aesthetics of landscape culture during a European trip he took with his father in 1784 and 1785. In England young Daniel was introduced to the pursuit of picturesque travel, which he later pursued back home. At the end of the 18th century a growing fascination with native scenery fueled the development of landscape art and landscape culture in the United States. Prints, paintings, travel guides, travel literature, treatises on aesthetics, and tourism became increasingly popular and in demand. Travelers in the “new world” educated themselves about landscape culture by reading the works of prominent English writers, such as William Gilpin, Uvedale Price, and Richard Payne Knight, whose books were by this time widely available in America. Wadsworth and other Americans thus acquired their understanding of the basic categories of the beautiful, the sublime, and the picturesque.[2]

Wadsworth was first exposed to the aesthetics of landscape culture during a European trip he took with his father in 1784 and 1785. In England young Daniel was introduced to the pursuit of picturesque travel, which he later pursued back home. At the end of the 18th century a growing fascination with native scenery fueled the development of landscape art and landscape culture in the United States. Prints, paintings, travel guides, travel literature, treatises on aesthetics, and tourism became increasingly popular and in demand. Travelers in the “new world” educated themselves about landscape culture by reading the works of prominent English writers, such as William Gilpin, Uvedale Price, and Richard Payne Knight, whose books were by this time widely available in America. Wadsworth and other Americans thus acquired their understanding of the basic categories of the beautiful, the sublime, and the picturesque.[2]

By the 1820s, with settlement well under way, American writers Benjamin Silliman and Theodore Dwight, both from Connecticut and both friends of Wadsworth, were publishing accounts of their travels, celebrating the American wilderness, and encouraging the rise of tourism among a broader public. Wadsworth made important contributions to the earliest developments of this landscape culture in the United States through his collaborations with Silliman and painter John Trumbull. As arbiters of taste, these men drew attention to the virtues of the American landscape. Trumbull ‘s View on the West Mountain near Hartford based on his sketches of the site, captured the picturesque possibilities of the property that Wadsworth later turned into his country estate.

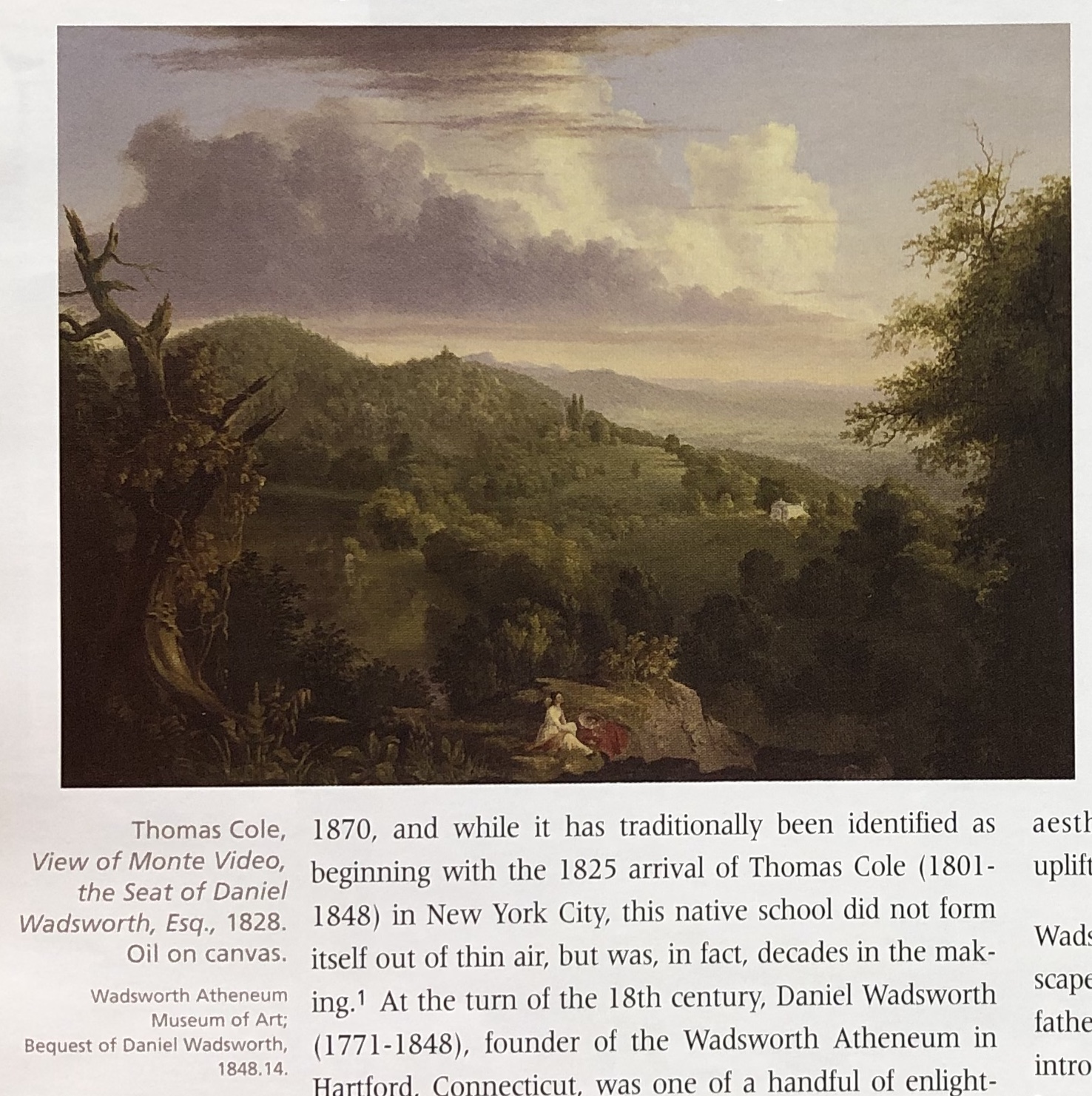

In 1805, in partnership with Trumbull, Wadsworth began transforming the wilderness tract of land on the summit of Talcott Mountain, west of Hartford, into a carefully cultivated summer retreat with a neo-Gothic house, surrounding gardens, a boathouse for the nearby mountain lake, and a working farm. He named the estate Monte Video, completing it by about 1810 with the construction of its most distinctive feature, a 55-foot high viewing tower that offered a spectacular view of the surrounding scenery.

In 1819 Wadsworth and Silliman traveled from Hartford to Quebec, which resulted in Remarks made, on a Short Tour, between Hartford and Quebec in the Autumn of 1819 written by Silliman, with illustrations after Wadsworth’s drawings. In the introduction Silliman expressed the beliefs he shared with Wadsworth and others: “National character often receives its peculiar cast from natural scenery … Thus natural scenery is intimately connected with taste, moral feeling, utility and instruction.” Silliman’s remarks included a detailed description of Monte Video. Wadsworth later commissioned Thomas Cole to paint View of Monte Video, the Seat of Daniel Wadsworth, Esq . While Trumbull’s earlier painting of the site reveals his reliance on the compositional conventions of the Old World, Cole dispensed with these traditions in an effort to convey the visual mastery that this mountaintop locale afforded the viewer in the grand panoramic sweep of the scenery.[3] To elevate the taste of American citizens, Wadsworth opened the property to the public, encouraging visitors to enjoy his wilderness estate.

Wadsworth traveled throughout the eastern United States making sketches of such well-known natural wonders as Niagara Falls and the Natural Bridge in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley; unexplored wilderness territory of the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the Susquehanna River Valley in New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland; and his jaunts in celebration of local scenery in the Connecticut River Valley. His New England sketches, made during trips with Silliman and Theodore Dwight, were reproduced as engravings and lithographs to illustrate accounts of their picturesque tours.

Beginning in 1805 Wadsworth and Trumbull made trips to Niagara Falls to view and sketch the natural wonder. For its scale, power, and sublimity, Niagara Falls achieved aesthetic preeminence during the first half of the 19th century, becoming the most frequently painted natural wonder in the United States. Its importance lay in the fact that it had no equal in the Old World, allowing Americans to claim cultural prominence.[4] Nearly every landscape painter of the period accepted the challenge of capturing the falls on canvas. Trumbull painted several of the earliest views including, Niagara Falls from an Upper Bank on the British Side and Niagara Falls from Below the Great Cascade on the British Side (both 1807) which Wadsworth acquired in 1828. Alvan Fisher, another artist associated with the Hudson River school who also enjoyed Wadsworth’s patronage, was one of a number of native-born painters to specialize in the production of paintings of the falls. He also painted four views of Monte Video which Wadsworth purchased.

Beginning in 1805 Wadsworth and Trumbull made trips to Niagara Falls to view and sketch the natural wonder. For its scale, power, and sublimity, Niagara Falls achieved aesthetic preeminence during the first half of the 19th century, becoming the most frequently painted natural wonder in the United States. Its importance lay in the fact that it had no equal in the Old World, allowing Americans to claim cultural prominence.[4] Nearly every landscape painter of the period accepted the challenge of capturing the falls on canvas. Trumbull painted several of the earliest views including, Niagara Falls from an Upper Bank on the British Side and Niagara Falls from Below the Great Cascade on the British Side (both 1807) which Wadsworth acquired in 1828. Alvan Fisher, another artist associated with the Hudson River school who also enjoyed Wadsworth’s patronage, was one of a number of native-born painters to specialize in the production of paintings of the falls. He also painted four views of Monte Video which Wadsworth purchased.

Thomas Cole, the acknowledged founder of the Hudson River school, was the premier landscape painter of his day, far more cerebral than those who had come before him. Cole used landscape art as a means of upholding traditional beliefs as he warned Americans of the dangers of material progress, unlimited democracy, and expansionism, which he believed were rampant in the Jacksonian era. Trumbull was among the first to recognize Cole’s genius and introduced the artist to Wadsworth in 1825. By then Wadsworth had spent over 25 years exploring the American landscape in his travels, writings, and sketches. A shared exposure to British landscape theory-Cole was English-proved a strong bond between them. Wadsworth became Cole’s most important early patron, and the two men remained close friends and correspondents until their deaths in 1848.

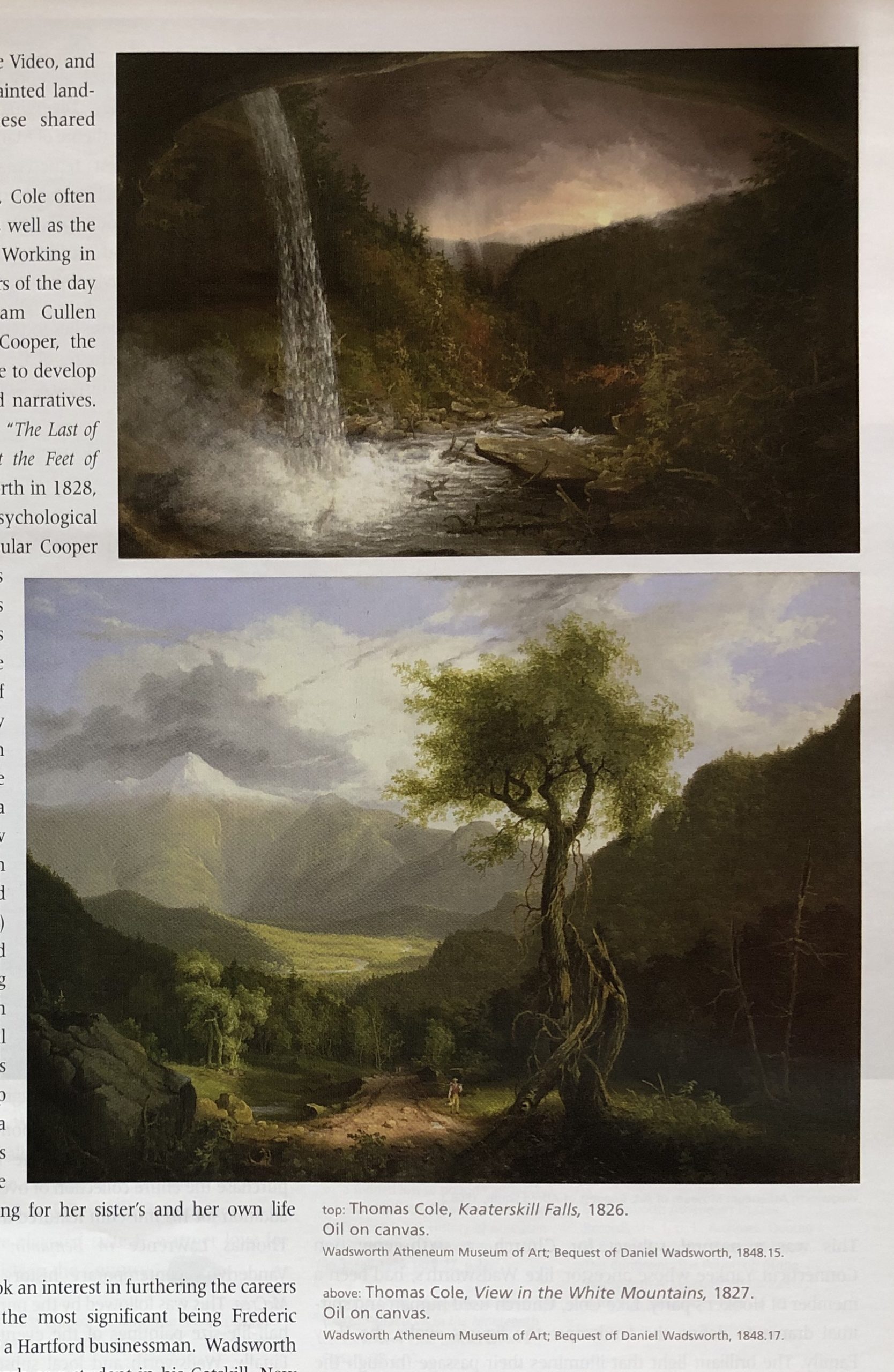

In a break from the European convention of landscape painting dominated by pastoral views, Cole’s early primary subject was the wilderness. As the first artist to depict the Catskill Mountain region in New York State, Cole painted its most spectacular sites, including Kaaterskill Falls, commissioned by Wadsworth in 1826, in which he eliminated all signs of tourism and instead presented images of the pristine wilderness of the past. This work epitomized the romantic sublime-storms sweep across the sky and natural forms of rocks and gnarled branches of dead trees assume anthropomorphic forms. Cole placed the figure of an Indian in the left foreground as sole witness to the purity of American wilderness.

Wadsworth appreciated the lofty goals that Cole set for his landscape art and commissioned many of the artist’s most important early paintings. He introduced Cole to the beauty of New England, including the Hartford area and Monte Video, and the White Mountains. Cole painted landscapes for Wadsworth of these shared favorite sites.[5]

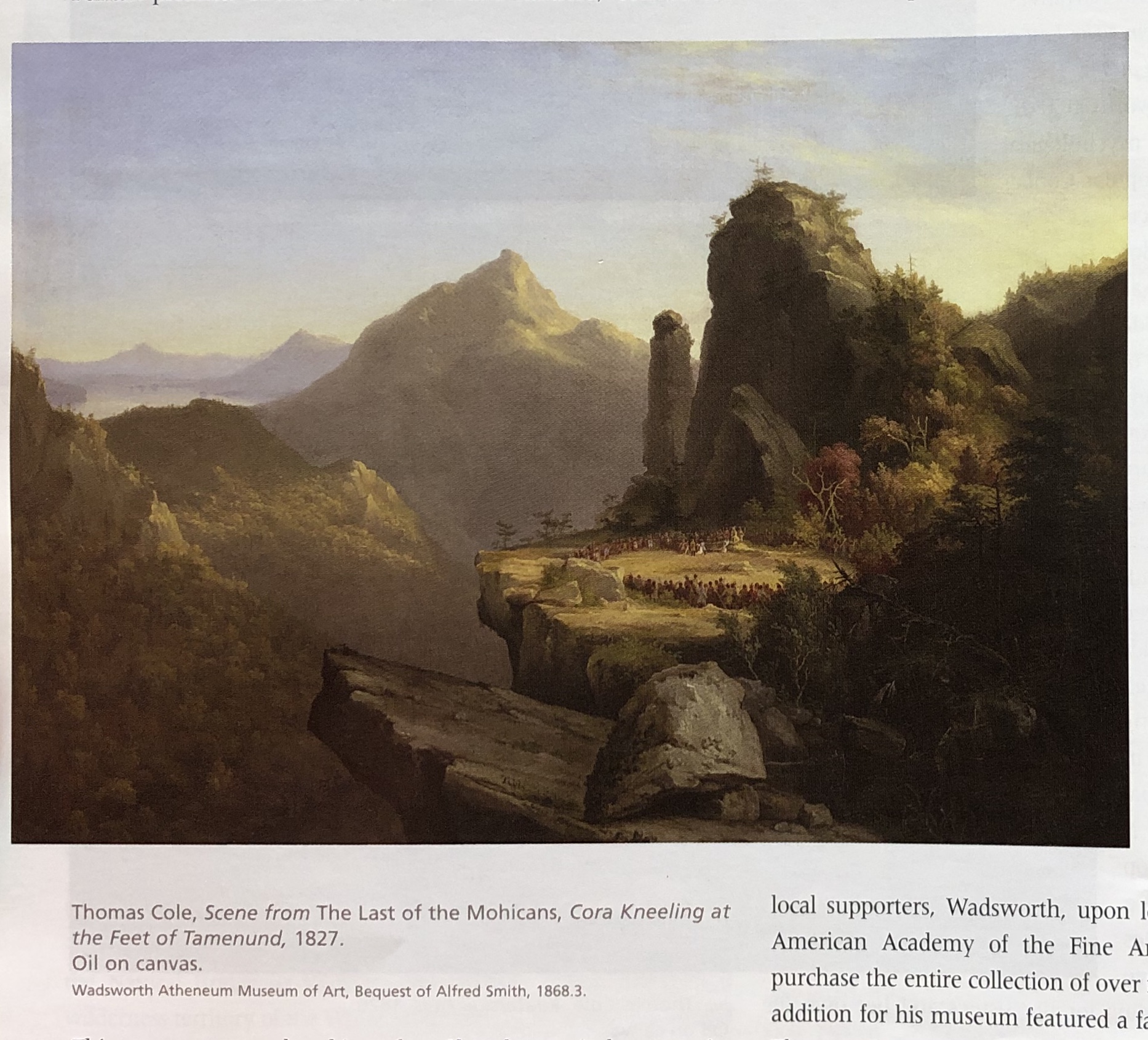

For his landscape compositions, Cole often used contemporary literature as well as the Bible for his pictorial themes. Working in concert with such leading writers of the day as Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant, and James Fenimore Cooper, the artist used landscape as a vehicle to develop American historical themes and narratives. For example, Cole’s Scene from The Last of the Mohicans, Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund , acquired by Wadsworth in 1828, uses landscape to convey psychological meaning. Drawn from the popular Cooper novel, this work reflects American settlers’ attitudes toward Native Americans as savages. In the novel the episode takes place in the vicinity of Lake George in upstate New York , but in the composition real and idealized imagery are combined. Cole includes both a faithful rendering of New Hampshire ‘s White Mountain scenery (which he considered the finest he had ever beheld) at upper left, and idealized geological features enhancing the minute narrative scene in the foreground.[6] The sexual tension in Cooper’s novel is evoked by a rocking stone atop a huge phallic pinnacle, and a dark cave, which provides a backdrop for the narrative scene of the young girl pleading for her sister’s and her own life in front of the Indian chief.[7]

For his landscape compositions, Cole often used contemporary literature as well as the Bible for his pictorial themes. Working in concert with such leading writers of the day as Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant, and James Fenimore Cooper, the artist used landscape as a vehicle to develop American historical themes and narratives. For example, Cole’s Scene from The Last of the Mohicans, Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund , acquired by Wadsworth in 1828, uses landscape to convey psychological meaning. Drawn from the popular Cooper novel, this work reflects American settlers’ attitudes toward Native Americans as savages. In the novel the episode takes place in the vicinity of Lake George in upstate New York , but in the composition real and idealized imagery are combined. Cole includes both a faithful rendering of New Hampshire ‘s White Mountain scenery (which he considered the finest he had ever beheld) at upper left, and idealized geological features enhancing the minute narrative scene in the foreground.[6] The sexual tension in Cooper’s novel is evoked by a rocking stone atop a huge phallic pinnacle, and a dark cave, which provides a backdrop for the narrative scene of the young girl pleading for her sister’s and her own life in front of the Indian chief.[7]

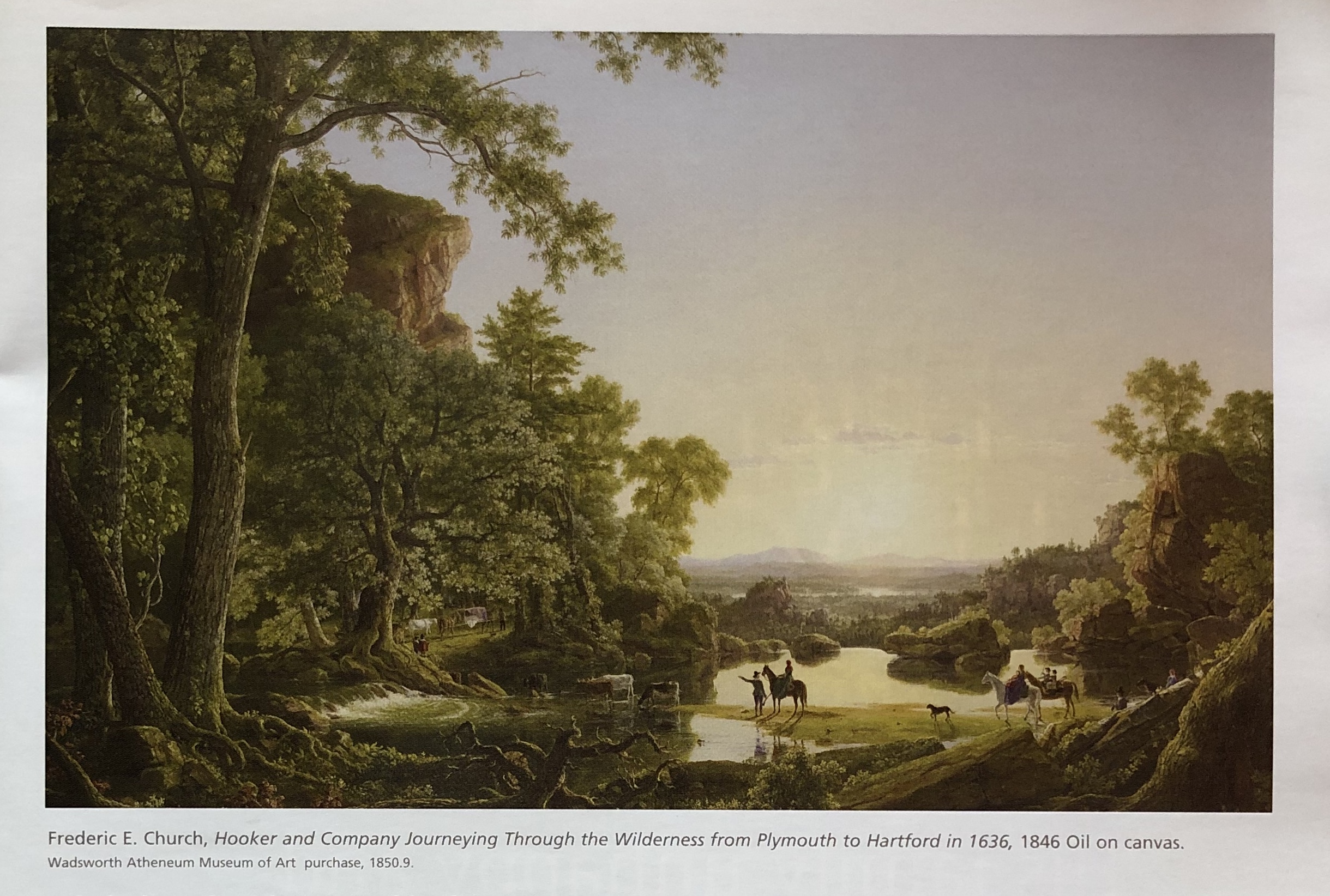

In his final years Wadsworth took an interest in furthering the careers of a number of local artists the most significant being Frederic Church (1826-1900), the son of a Hartford businessman. Wadsworth convinced Cole to take on Church as a student in his Catskill, New York, studio. Church spent the years 1844-1846 absorbing the lessons Cole imparted including a love of nature and an ambition to embrace elevated historical and moralistic themes for his landscape paintings.

Frederic Church’s earliest works followed Cole’s precept to paint a “higher style of landscape.” In his first ambitious composition, Hooker and Company Journeying through the Wilderness from Plymouth to Hartford in 1636 (which Wadsworth acquired for his museum in 1846), Church chose to paint a heroic event drawn from colonial history-the migration of a band of religious dissidents led by the Puritan preacher Thomas Hooker to found Hartford, Connecticut. This was a natural subject for Church, a sixth-generation Connecticut Yankee whose ancestor, like Wadsworth’s, had been a member of Hooker’s party. Like Cole, Church used human and spiritual drama to define the landscape; the figures evoke the Holy Family. The brilliant light that illumines their passage through the wilderness completes the allegory of divine providence at work in the Connecticut Valley. Diverging from his teacher’s pessimism, Church embraced the theme of Manifest Destiny in this work, which is one of the earliest representations of westward expansion. Landscape features such as the historic Charter Oak Tree, seen at the left, and the anthropomorphic forms of the gnarled trees and rocks in the foreground and center right, along with the stylized rays of sunlight symbolic of divine light, enhance the meaning of the painting.

Church maintained close ties to Hartford. He sketched local scenery, and returned to the theme of Connecticut ‘s colonial history for a number of important historical landscapes, including several paintings of the Charter Oak Tree. In the years just after the Civil War Church, by then the country’s most renowned artist, guided the formation of the private picture gallery of Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt of Hartford, the widow of arms manufacturer Samuel Colt.

In 1841, one month after his 70th birthday, Wadsworth made formal plans to found a public institution that would house his substantial art collection. He announced his intention to build “a Gallery of Fine Arts” by making a gift of his lot of land on Main Street in Hartford.[8] In addition to his own collection, which he intended to bequeath, he acquired a number of important paintings for the new museum. With the help of local supporters, Wadsworth , upon learning of the demise of the American Academy of the Fine Arts in New York , moved to purchase the entire collection of over fifty paintings. This important addition for his museum featured a famed, full-scale portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence of Benjamin West, 1818-1821, and John Vanderlyn’s contemporary history painting, The Murder of Jane McCrea. This was followed by the purchase of Trumbull ‘s series of five half-life-size history paintings of the events of the American Revolution. Finally, Wadsworth and local subscribers purchased a new grand scale landscape by Cole-a masterful Italian scene, Mt. Etna from Taormina.

In 1844 the doors of the museum opened to the public where visitors could view contemporary American landscapes by the country’s leading painters, and works by European old masters. The collection was housed in the central nave of the Gothic Revival building designed by Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis, while the Connecticut Historical Society, the Young Men’s Institute (to become the Hartford Public Library in 1893), and the Natural History Society were housed in separate wings. That year Cole applauded Wadsworth ‘s vision. In a letter to Wadsworth’s lawyer, Alfred Smith, he wrote, “I assure you that I shall feel proud of having a picture of mine in your Gallery & hope the example you are about to set, in forming a permanent Gallery, will be followed in other places & be the means of producing a more elevated taste & warmer love for beautiful Art than at present exists in the Country.”

In 1844 the doors of the museum opened to the public where visitors could view contemporary American landscapes by the country’s leading painters, and works by European old masters. The collection was housed in the central nave of the Gothic Revival building designed by Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis, while the Connecticut Historical Society, the Young Men’s Institute (to become the Hartford Public Library in 1893), and the Natural History Society were housed in separate wings. That year Cole applauded Wadsworth ‘s vision. In a letter to Wadsworth’s lawyer, Alfred Smith, he wrote, “I assure you that I shall feel proud of having a picture of mine in your Gallery & hope the example you are about to set, in forming a permanent Gallery, will be followed in other places & be the means of producing a more elevated taste & warmer love for beautiful Art than at present exists in the Country.”

Elizabeth Mangan Kornhauser was the Kribble Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

Explore!

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

600 Main Street Hartford

the wadsworth.org

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art history on our TOPICS page.

Footnotes

1. “Hudson River school” was originally intended as a derogatory label, first used in the late 1870s, that called attention to the provinciality of the painters.

2. For much of the 18th century Edmund Burke’s definitions of the beautiful, meaning the harmonious, sensual, feminine aspects of nature, and the sublime, which he associated with the harsh, masculine, horrific aspects of nature, were widely accepted.

3. Caleb’s painting hints at the experience of what he calls the ‘panoptic sublime’ that was afforded by the view from the tower, providing both panoramic or visual mastery of the scene with telescopic vision resulting in “a sudden loss of boundaries.” See Alan Wallach, “Wadsworth’s Tower: An Episode in the History of American Landscape Vision,” American Art, 10, no. 3, Fall 1996, pp. 8-27, p. 22.

4. John F. Sears, Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 13.

5. For a full discussion of Cole’s paintings for Wadsworth, and related correspondence between them, see, Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, American Paintings Before 1945 in the Wadsworth Atheneum, 2 vols, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), vol 1, pp. 219-247.

6. Thomas Cole to David Wadsworth, August 4, 1827, in J. Bard McNulty ed., The Correspondence of Thomas Cole and Daniel Wadsworth, Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1983, p. 12.

7. Richard Slotkin, introduction to James Fenimore Cooper, Last of the Mohicans, New York: Penguin, 1988, pp. ix-xxviii.

8. Wadsworth Atheneum Trustee Records, vol 1., p. 1. Archives. Quoted in Eugene R. Gaddis, “Foremost Upon This Continent: The Founding of the Wadsworth Atheneum,” in Connecticut History 26 (November, 1985), p. 99.