By Ramin Ganeshram and Elizabeth Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

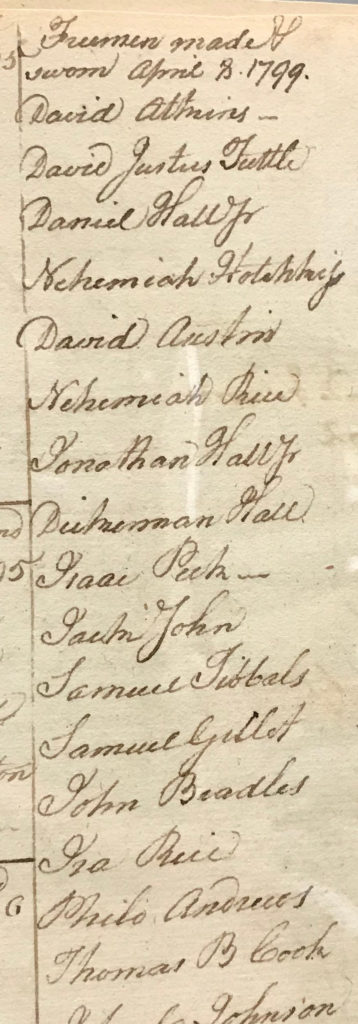

In the early years of the 19th century, when the American Republic was still a very new experiment, two men—Jack John and Toby Birdseye—registered to vote in Wallingford, Connecticut in 1799 and 1803 respectively. They easily satisfied the state’s requirements for freemen (registered voters). Both men were of age. John’s landholdings equaled 15 acres, and his estate upon his death in 1816 was valued at $2,800. Birdseye owned three-quarters of an acre of land and a portion of a sawmill.

John and Birdseye’s admission to the freeman rolls however, was caught in the crossfire of the struggle for control of the state between the Federalist Standing Order and the upstart Democratic-Republicans. Birdseye was subjected to a smear campaign in which he was accused of criminal assault in order to oust him from the rolls.

In the eyes of their fellow freemen, John and Birdseye shared one serious disqualifying flaw: they were black.

“White” Previously Not Specified

According to constitutional law scholar Wendy Van Wie, a former law professor at Albany Law School, voting rights must first be viewed through the lens of what was conferred via the U.S. Constitution. Although it was a radical leap toward “government by the people” in 1787 when the world was otherwise dominated by monarchy and absolute power, the United States Constitution did not actually confer the right to vote on anyone, instead leaving that decision specifically to individual states. “Voters did not vote for president, for United States senators, or electors to the electoral college. There would be no popular election of U.S. senators until after the 17th Amendment was adopted in 1913,” says Van Wie. “State legislatures determined how members of the electoral college were chosen for the purpose of electing the president of the United States.”

All of the original 13 colonies except Connecticut and Rhode Island adopted constitutions within a few years of the declaration of American independence in 1776. Generally, under these first state constitutions, a person qualified to vote if he was 21 years of age, male (although New Jersey alone initially made no gender distinction), met a residency requirement, and was a taxpayer and/or property owner.

Being of a certain race was not a qualification for voting in 8 of the original 13 state constitutions (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire, New York, or North Carolina) nor in the charters that still governed Connecticut and Rhode Island. Indeed, in independence-era America, only the constitutions of South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia barred blacks from voting.

As the 18th century drew to a close, the African American population in Connecticut held steady at about 6,500 people, according to colonial census data and research extrapolations—equal to the number of people enslaved in the state at the beginning of the American Revolution. But by the early 1800s nearly 80 percent were free. This transformation was thanks to the American Revolution during which many enslaved people gained their freedom by running away, by fighting for the British or the Americans (both of whom promised freedom in exchange for their service), or through the state’s gradual abolition law, which was enacted in 1784. Connecticut’s gradual abolition law provided that black and mulatto children born after March 1 of that year would become free at age 25. A 1797 act reduced that age to 21. This remained the law of the land until 1848 when slavery was outlawed in the state. This change in the status of blacks, who were slowly gaining an economic foothold in the state, raised fears of black voting among white Connecticut freemen.

As Connecticut’s enslaved persons like Jack John and Toby Birdseye gained emancipation, some may have pursued the right to vote based on the lack of race-based disqualification and their own property ownership (though precious few records have been found to date). Jack John had been manumitted in 1782 and eventually owned 26 acres of land, thereby fulfilling both the free status and the landowning requirement to become a registered voter. He was admitted a freeman in Wallingford in 1799. Toby Birdseye had been freed in 1798 and owned land and a portion of a sawmill. He was admitted as a freeman in Wallingford in 1803. While voting records do not exist, it’s likely the men voted in Wallingford.

In 1801 and 1802 the general assembly enacted stricter laws for entry to the freeman rolls. These were pushed through by Federalists attempting to stall gains by Jeffersonian Republicans who supported what they called “universal” suffrage—that is, enabling more white men to qualify to vote via removal of the property requirement. However, without a specific race requirement there remained the potential for emancipated blacks to benefit as well.

Federalists also added a requirement that freeman (voters) be approved by selectmen and the justice of the peace and a stand-up vote (instead of secret ballot) during the nominating process. There was also further tightening of property qualifications, including that satisfaction of the property requirement be made and approved four months in advance of the freemen’s meeting (when those eligible to vote were registered) to reduce fraud.

In 1803 Federalists waged an attack in the press on Wallingford’s freemen’s meeting—the one at which Toby Birdseye was admitted with 24 other men. Federalists accused Wallingford of admitting 15 white men who did not meet the property requirement. They accused Birdseye of a moral disqualification (since he met the property requirement), saying he had attempted to rape a white woman. They invoked the qualification that one demonstrate “quiet and peaceable behavior and civil conversation” to nullify his freeman voting status. No criminal record has been found to substantiate this claim.

In 1814 the Connecticut legislature inserted the word “white” into the freeman statute. This move may have been precipitated by concern that free blacks would register to vote as Democratic-Republicans. In response Bias Stanley and William Lanson, two African Americans from New Haven, filed a petition with the general assembly asking to be exempted from paying taxes since they had been denied the vote. A group of black men from Norwich and New London made a similar petition in 1817. Their petitions were denied. (See “No Taxation Without Representation,” Spring 2016.)

From 1817 to 1818 the Toleration Party took control of state government. The stand-up law was repealed in October 1817, and in May 1818 the legislature expanded the suffrage by essentially dropping the property requirement, only vaguely requiring “possession of real, or personal estate.”

Ultimately, however, the Toleration Party would not prove to be sympathetic to black suffrage. African Americans were not included in the idea of universal suffrage. In October 1818 the new constitution was adopted. It outlined a white-race requirement for voters, thereby making it a constitutional imperative that African Americans be deprived of equal representation in state government. As Jack Chatfield notes in his introduction to volume 17 of the Public Records of the State of Connecticut, “In a state buffeted by fierce political controversies, a consensual white supremacy led to a re-definition of the republican civic community.”

Over the course of the next 50 years, free African Americans filed a series of petitions to the Connecticut legislature asking to be exempted from paying property tax or asking for the right to vote. None were successful.

Connecticut Falls in Line with the South

By the time Connecticut adopted its first constitution in 1818, the trend in the states was emphatically toward qualifying only white men as voters. Although the Kentucky, Tennessee, and Vermont constitutions were initially silent about race in their voter qualification provisions, by 1799 Kentucky had replaced its first constitution with a new one that provided that: “every free male citizen (negroes, mulattoes, and Indians excepted) . . . shall enjoy the right of an elector.” All of the new states admitted to the Union between 1800 and 1818 (Ohio, Louisiana, Indiana, Mississippi, and Illinois) included “white male” in their voter qualifications. In addition, the original states of Delaware (in 1792) and Maryland (in 1810) changed their Independence-era constitutions to add “white” to their voter qualifications. Of the 13 states newly admitted to the Union after 1818 but before the Civil War, only Maine’s constitution (adopted in 1820) allowed blacks to vote.

Acting well within the mainstream of the times when it added “white” to its qualifications for voting in 1814, Connecticut was, however, out of step with its New England neighbors. The constitutions of Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island did not include the word “white” in their voting provisions.

There were several failed attempts to amend the voting law in the 1840s and 1850s according to Matthew Warshauer in Connecticut and the American Civil War (Wesleyan University Press, 2011). In 1845 and 1850 African American petitioners sought to amend the state constitution by asking the legislature to, as written in the 1850 petition, “take the necessary measures for amending the Constitution of this State by expunging the word white in the first line of the 2nd Section of the 6th Article of Said Constitution.” The petitions were rejected.

In 1864 another amendment was proposed. Governor William Buckingham said to the general assembly, “We are now battling for the inalienable rights of man, without regard to race or color. In this struggle the colored man, hitherto degraded and oppressed, have, in every section of the country, been on the side of the government, and are now in our armies by thousands fighting for freedom under the protection of law. Let us inspire the colored man … by granting him the boon so long withheld.”

In 1864 another amendment was proposed. Governor William Buckingham said to the general assembly, “We are now battling for the inalienable rights of man, without regard to race or color. In this struggle the colored man, hitherto degraded and oppressed, have, in every section of the country, been on the side of the government, and are now in our armies by thousands fighting for freedom under the protection of law. Let us inspire the colored man … by granting him the boon so long withheld.”

The Democrats—who had sought more liberal suffrage in the years leading to the constitution convention—came out strongly against black suffrage notes Warshauer, citing the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision that no black, free or enslaved, was a citizen. They argued that it was therefore unconstitutional to extend the franchise to African Americans in Connecticut. Connecticut’s Supreme Court issued a decision that “a free colored person born in this State is a ‘citizen’ of this State, and of the United States.” Despite heated and rancorous debate, the assembly voted in favor of the amendment. It next went to a public referendum in October 1864 but it failed by a substantial margin.

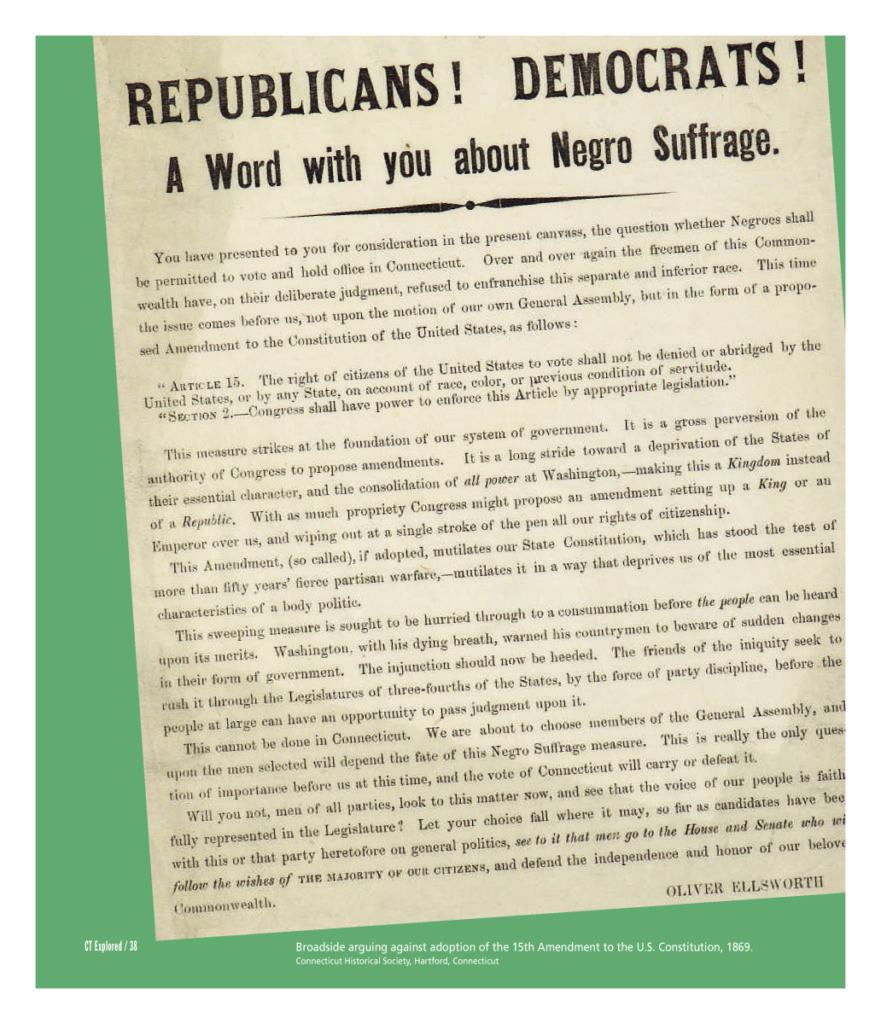

After the Civil War, in 1870, the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, stating that no man could be denied the right to vote based on race or previous condition of servitude. As it had in matters of slavery, abolition, and enfranchisement Connecticut continued to take a more southern approach protesting any federal efforts to delineate the nature of voting rights.

A broadside petition published in 1869 claimed the U.S. Congress was trying to consolidate authority over state’s rights via the enactment of the 15th Amendment. It called the proposed amendment a “gross perversion of the authority of Congress” that would, if adopted, “mutilate” the Connecticut state constitution. After six years of bitter and protracted debate, Connecticut amended the state constitution to reflect the federal law in 1876.

Ramin Ganeshram is executive director of Westport Historical Society and curator of the society’s exhibition “Rights For All?” The Connecticut Constitution of 1818 and “Remembered: The History of African Americans in Westport.” Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Ramin Ganeshram is executive director of Westport Historical Society and curator of the society’s exhibition “Rights For All?” The Connecticut Constitution of 1818 and “Remembered: The History of African Americans in Westport.” Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

“No Taxation without Representation: Black Voting in Connecticut,” Spring 2016

Read more stories about the Constitution of 1818 and African Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS pages.