Alexander Calder, “Stegosaurus,” 1972, Main Street, Hartford. photos: Mary M. Donohue, Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism

By Ann Harrison and Mary M. Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2006/2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Outdoor sculpture merges art and history, timeless ideals and topical politics. Highly visible and easily accessible, it is meant to withstand the elements, public scrutiny, and the test of time. It reflects artistic expression but also represents a community’s collective experience, depicting events or people the community considers significant and giving a sense of how the community hopes to be remembered. Public sculptures, unlike those in museums or protected spaces, take meaning from their context. And, because they’re not easily moved, their meanings may shift as their physical environments evolve.

The Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism and the editors of Hog River Journal have put together a “Top 10” list of outdoor public sculptures in Connecticut. Sculptures were chosen from every corner of the state. Each has an interesting history and story to tell. Each has a special connection to Connecticut, whether carved from Connecticut granite, brownstone, or marble, cast in zinc during our industrial heyday, or created by nationally known sculptors who made Connecticut home. Not all are shining examples; a few have made this list especially for their need for attention. Think of this as a wake-up call for some, a celebratory ring for others.

Celebrating Connecticut’s cache of public sculpture should not end with this list. More than 475 pieces of Connecticut’s publicly accessible, non-commercial outdoor sculpture have been researched and entered into the Connecticut Statewide Historic Resource Inventory and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American Art’s Inventory of American Sculpture. New pieces of outdoor sculpture are added to the state inventory as they are dedicated each year. Both databases can be accessed through the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism Web site, www.cultureandtourism.org. The Connecticut inventory, with photos (including many used here), is also on file at the Commission’s Historic Preservation and Museums Division office, 59 South Prospect Street, Hartford, (860) 566-3055. Have a look — and then plan a trip to visit your own top ten.

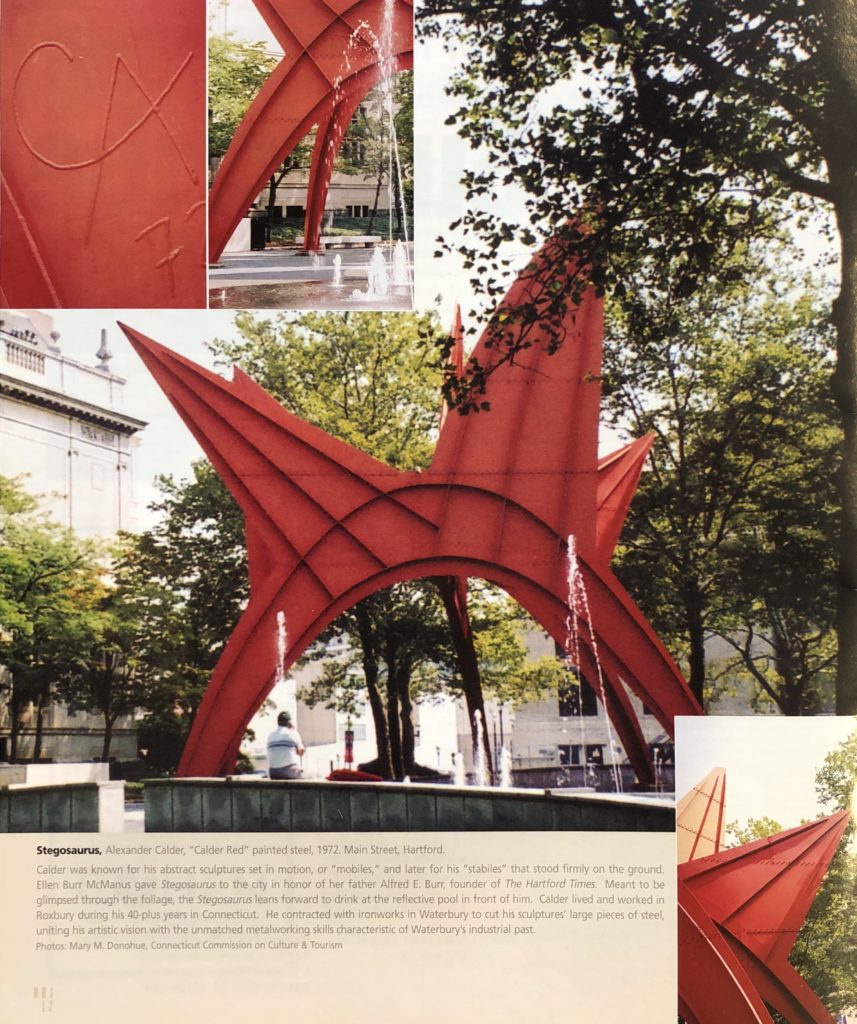

Above: Stegosaurus, Alexander Calder, “Calder Red” painted steel, 1972, Main Street, Hartford.

Calder was known for his abstract sculptures set in motion, or “mobiles”, and later for his “stabiles” that stood firmly on the ground. Ellen Burr McManus gave Stegosaurus to the city in honor of her father Alfred E. Burr, founder of the Hartford Times. Meant to be glimpsed through the foliage, the Stegosaurus leans forward to drink at the reflective pool in front of him. Calder lived and worked in Roxbury during his 40-plus years in Connecticut. He contracted with ironworks in Waterbury to cut his sculptures’ large pieces of steel, uniting his artistic vision with the unmatched metalworking skills characteristic of Waterbury’s industrial past.

Frances Laughlin Wadsworth, “American School for the Deaf Founders Memorial,” 1952, Farmington Avenue, Broad Street, Asylum Avenue, Hartford. photo: American School for the Deaf

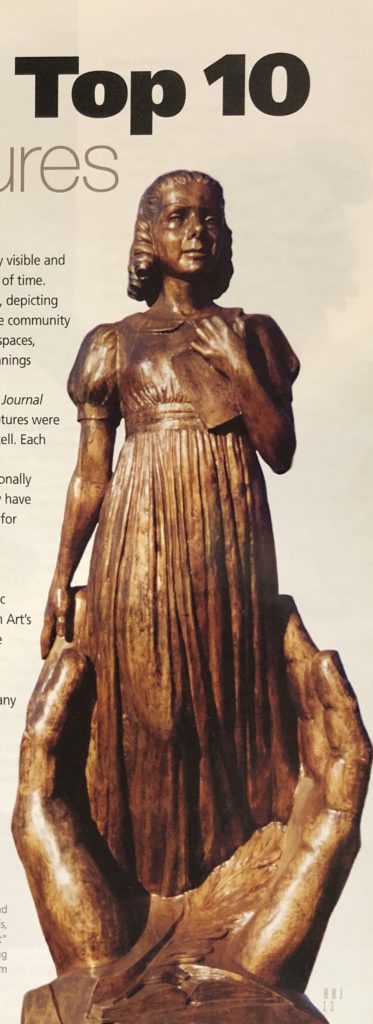

American School for the Deaf Founders Memorial, Frances Laughlin Wadsworth, bronze and granite, 1952. Farmington, Broad and Asylum Avenues, Hartford.

Hartford’s most beloved statue represents Alice Cogswell, the school’s first deaf student and daughter of founder Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell. The little girl is protectively cradled in two hands, each finger symbolizing one of the school’s incorporators, the hands forming the word “light” in American Sign Language. The school operated at this location for 100 years befor moving to West Hartford. Frances Wadsworth was a Hartford negative and a student of Gutzon Borglum (see Wheeler Memorial Fountain). Photo: American School for the Deaf.

left: John M. Moffit and Alexander Doyle, “Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, 1887, East Rock Park, New Haven. photo: Ann Harrison. top right: Gutzon Borglum, Wheeler Memorial Fountain, 1912, Bridgeport. photo: Ann Harrison. bottom: John Massey Rhind, Corning Fountain, 1899, Bushnell Park, Hartford. photo: Mary M. Donohue

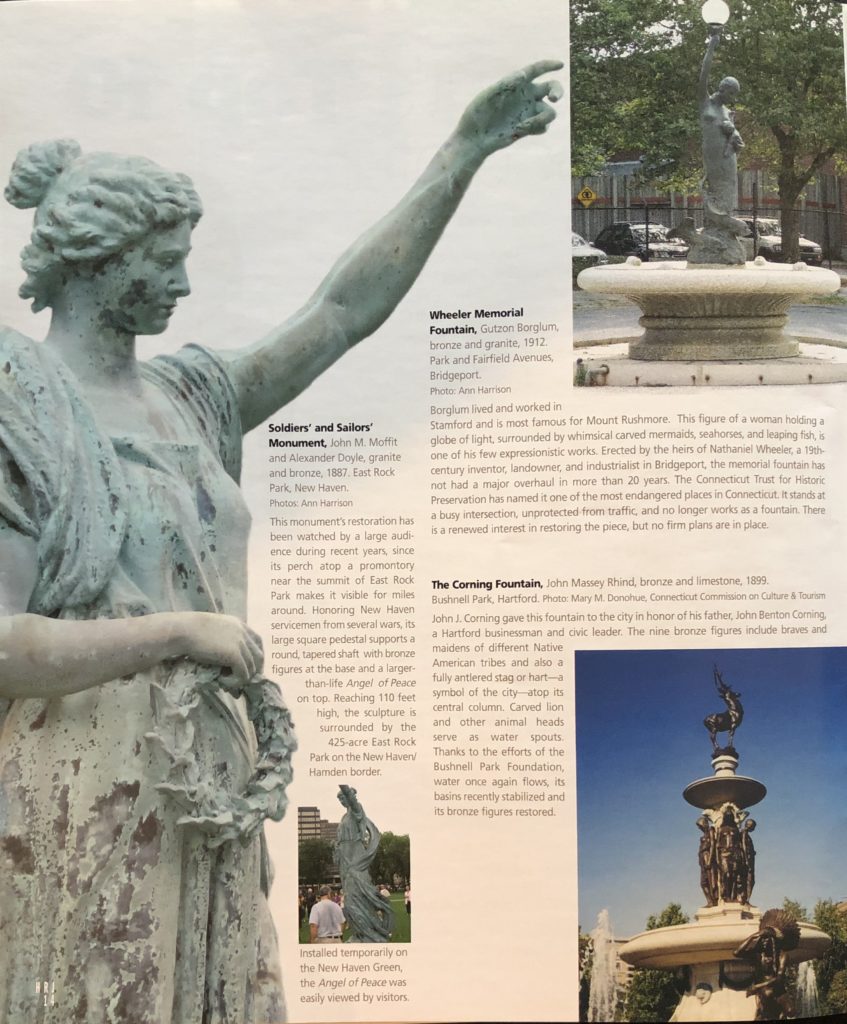

Above left: Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, John M. Moffit and Alexander Doyle, granite and bronze, 1887. East Rock Park, New Haven.

This monument’s restoration has been watched by a large audience during recent years, since its perch atop a promontory near the summit of East Rock Park makes it visible for miles around. Honoring New Haven servicemen from several wars, its large square pedestal supports a round, tapered shaft with bronze figures at the base and a larger-than-life Angel of Peace on top. Reaching 110 feet high, the sculpture is surrounded by the 425-acre East Rock Park on the New Haven/Hamden border. Installed temporarily on the New Haven Green, the Angel of Peace was easily viewed by visitors.

Above top right: Wheeler Memorial Fountain, Gutzon Borglum, bronze and granite, 1912, Park and Fairfield Avenues, Bridgeport.

Borglum lived and worked in Stamford and is most famous for Mount Rushmore. This figure of a woman holding a globe of light, surrounded by whimsical carved mermaids, seahorses, and leaping fish, is one of his few expressionistic works. Erected by the heirs of Nathaniel Wheeler, a 19th century inventor, landowner, and industrialist in Bridgeport, the memorial fountain has not had a major overhaul in more than 20 years. The Connecticut Trust for HIstoric Preservation has named it one of the most endangered places in Connecticut. It stands at a busy intersection, unprotected from traffic, and no longer works as a fountain. There is a renewed interest in restoring the piece, but no firm plans are in place.

Above bottom right: The Corning Fountain, John Massey Rhind, bronze and limestone, 1899. Bushnell Park, Hartford.

John J. Corning gave this fountain to the city in honor of his father, John Benton Corning, a Hartford businessman and civic leader. The nine bronze figures include braves and maidens of different Native American Tribes and also a fully antlered stag or hart — a symbol of the city — atop its central column. Carved lion and other animal heads serve as water spouts. Thanks to the efforts of the Bushnell Park Foundation, water once again flows, its basins recently stabilized and its bronze figures restored.

left: Evelyn Beatrice Longman Batchelder, “Spirit of Victory,” 1926. Bushnell Park, Hartford. photo: Loomis Chaffee Library. Right: Stanley Bleifeld,” Father Michael J. McGivney Statuary Group, 1990. Knights of Columbus, New Haven. photo: Ann Harrison

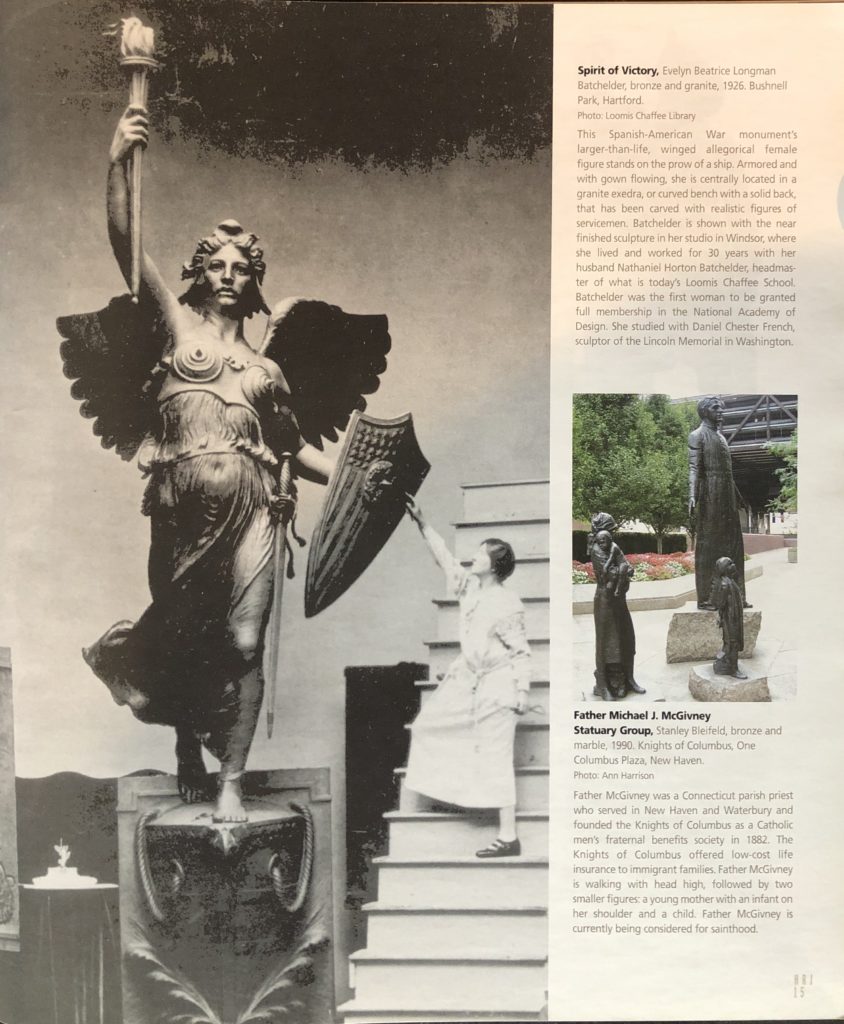

Above left: Spirit of Victory, Evelyn Beatrice Longman Batchelder, bronze and granite, 1926. Bushnell park, Hartford.

This Spanish-American War monument’s larger-than-life, winged allegorical female figure stands on the prow of a ship. Armored and with gown flowing, she is centrally located in a granite exedra, or curved bench with a solid back, that has been carved with realistic figures of servicemen. Batchelder is shown with the near finished sculpture in her studio in Windsor, where she lived and worked for 30 years with her husband Nathaniel Horton Batchelder, headmaster of what is today’s Loomis Chaffee School. Batchelder was the first woman to be granted full membership in the National Academy of Design. SHe studied with Daniel Chester French, sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington.

Above right: Father Michael J. McGivney Statuary Group, Stanley Bleifeld, bronze and marble, 1990. Knights of Columbus, One Columbus Plaza, New Haven.

Father McGivney was a Connecticut parish priest who served in New Haven and Waterbury and founded the Knights of Columbus as a Catholic men’s fraternal benefits society in 1882. The Knights of Columbus offered low-cost life insurance to immigrant families. Father McGivney is walking with head high, followed by two smaller figures; a young mother with an infant on her shoulder and a child. Father McGivney is currently being considered for sainthood.

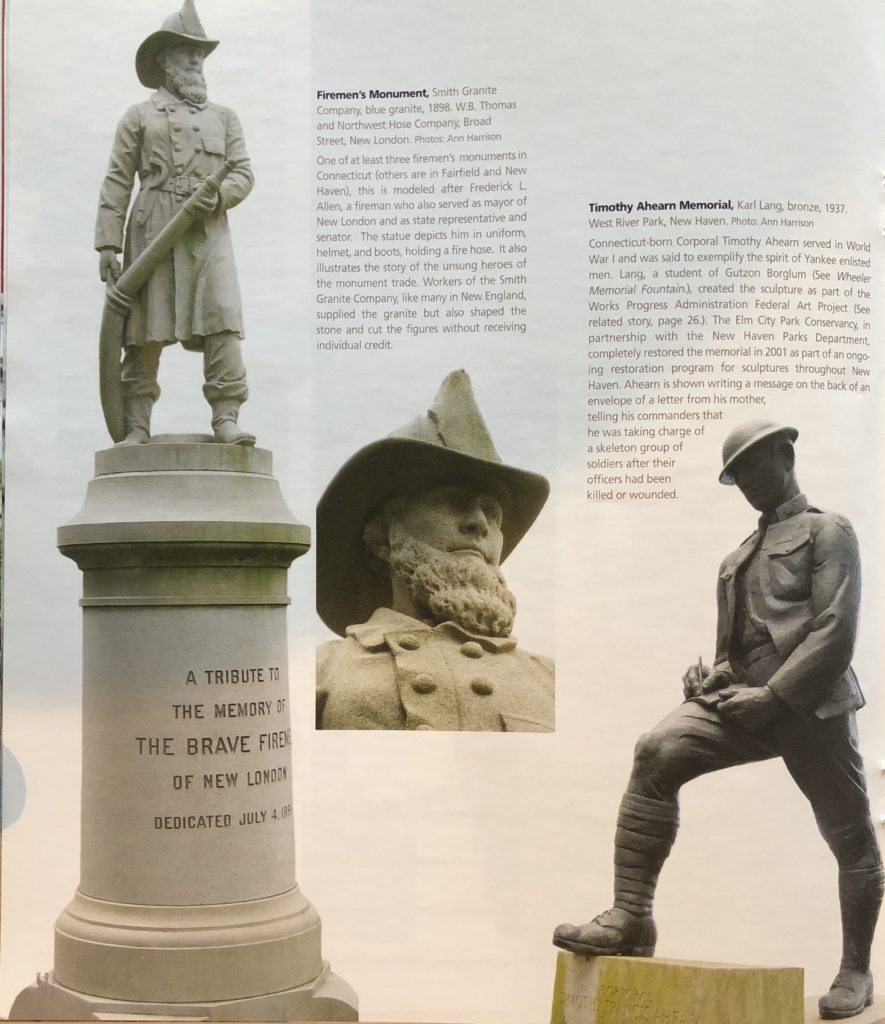

Above left: Firemens’ Monument, Smith Granite Company, blue granite, 1898. W.B. Thomas and Northwest Hose Company, Broad Street, New London. Photos: Ann Harrison

One of at least three firemen’s monuments in Connecticut (others are in Fairfield and New Haven), this is modeled after Frederick L. Allen, a fireman who also served as mayor of New London and as state representative and senator. The Statue depicts him in uniform, helmet, and boots, holding a fire hose. It also illustrates the story of the unsung heroes of the monument trade. Workers of the Smith Granite Company, like many in New England, supplied the granite but also shaped the stone and cut the figures without receiving individual credit.

Above right: Timothy Ahearn Memorial, Karl Lang, bronze, 1937. West River Park, New Haven. Photo: Ann Harrison

Connecticut-born Corporal Timothy Ahearn served in World War I and was said to exemplify the spirit of Yankee enlisted men. Lang, a student of Gutzon Borglum (see Wheeler Memorial Fountain), created the sculpture as part of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (see related story, page 26). The Elm City Park Conservancy, in partnership with the New Haven Parks Department, completely restored the memorial in 2001 as part of an ongoing restoration program for sculptures throughout New Haven. Ahearn is shown writing a message on the back of an envelope of a letter from his mother, telling his commanders that he was taking charge of a skeleton group of soldiers after their officers had been killed or wounded.

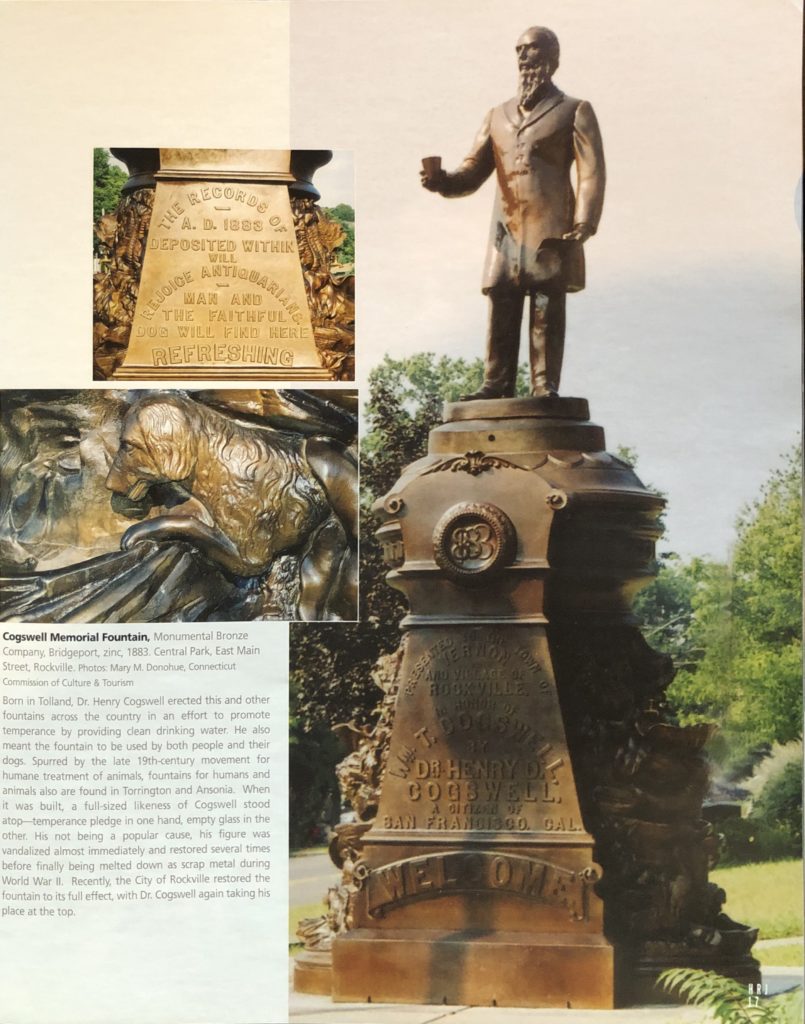

Above: Cogswell Memorial Fountain, Monumental Bronze Company, Bridgeport, zinc, 1883. Central Park, East Main Street, Rockville. Photos: Mary M. Donahue, Connecticut Commission of Culture & Tourism

Born in Tolland, Dr. Henry Cogswell erected this and other fountains across the country in an effort to promote temperance by providing clean drinking water. He also meant the fountain to be used by both people and their dogs. Spurred by the late 19th-century movement for humane treatment of animals, fountains for humans and animals also are found in Torrington and Ansonia. When it was built, a full size likeness of Cogswell stood atop — temperance pledge in one hand, empty glass in the other. His not being a popular cause, his figure was vandalized almost immediately and restored several times before finally being melted down as scrap metal during World War II. Recently the City of Rockville restored the fountain to its full effect, with Dr. Cogswell again taking his place at the top.

Ann Harrison is a freelance journalist and project editor for the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism. She and Mary Donohue co-wrote “The Conference State” for the Fall 2005 issue. Mary M. Donohue is the survey and grants director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism. She’s a frequent contributor to HRJ, most recently on Sophie Tucker in the Fall 2006 issue.

Explore!

“Two Controversial Statues: Standing … At Least for Now,” Spring 2018

“Connecticut’s Mount Rushmore Connection,” Spring 2015

“Calder in the Open Air,” Spring 2015

Read more stories about Connecticut’s Art History on our TOPICS page.