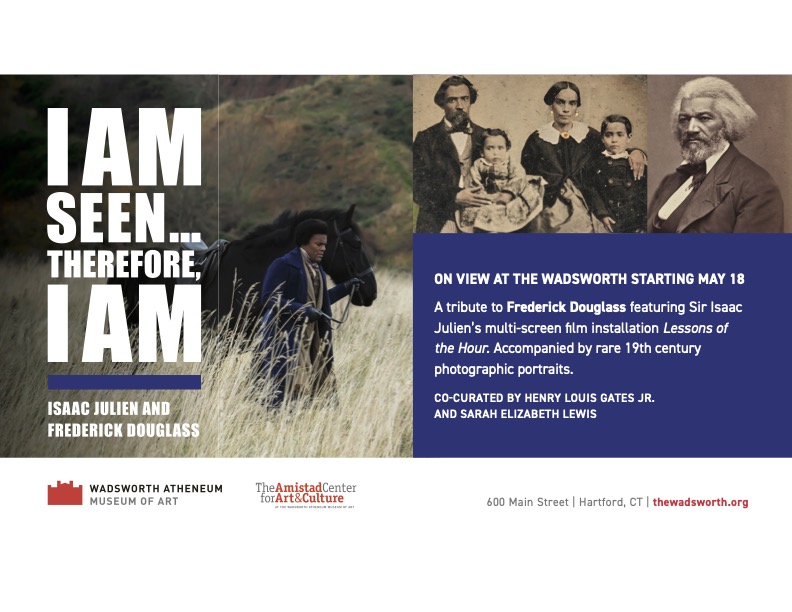

(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer, 2023

By Matthew Warshauer

Subscribe/buy the Issue

There’s a time when sugar ruled the world and Connecticut’s sweet tooth was insatiable. “Seafaring men” departed New England’s rocky shores in ships packed with a remarkable array of goods, returning with the nectar of West Indian production: sugar, molasses, and rum. Though Connecticut had only been established in 1636, by 1649, just 13 years later, enterprising men cast their gaze southward toward warmer climates and big profits.

A scene in the West Indies showing Natives on the beach with a British sailor and three large casks, and two ships in the harbor. image: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

In that year the merchants of Wethersfield and Hartford invested in a small vessel, fittingly named the Tryall, or “trial,” to trade with Barbados. The little ship departed the Connecticut River loaded with fresh produce, lumber, and barrel staves (the wooden slats that form the barrel). Those drums of trade soon returned, packed with sugar and molasses, the “gold” of their day.

To say that Connecticut’s early economy revolved around the West Indies trade is something of an understatement. Sugar, molasses, and rum were everything. While the mass of the colony’s farmers led a subsistence, barter existence, they still managed to grow a bit extra – both crops and livestock – to trade with the islands. A voyage took anywhere from two to five weeks, depending on weather and destination. Vessels ranged between 60 feet to 150 feet. Livestock were usually kept on deck, reserving room in the ship’s hold for other valuable cargo.

Even before Connecticut sent her first vessel, Samuel Wakeman and Samuel Pierce, merchants from Hartford, sailed to the West Indies in 1641 to explore the prospect of resettling on Providence Island, a colony off the coast of South America founded by English Puritans. Connecticut Explored publisher and historian Katherine Hermes, in a project called “Ties to the West Indies” for the Ancient Burying Ground Association, relates that John Pynchon of Springfield and Samuel Wyllys of Hartford purchased 25 acres on the Cabbage Tree Plantation in Antigua. On November 17, 1677, Wyllys provided money to Hartford’s Richard Lord “for promoting the design of the Plantation and sugar works” in Antigua. Lord made two voyages per year to the West Indies. The Puritans who settled New England were enterprising people, devoted to both their religious ideals and profit.

As Connecticut grew, so too did her relationship with the sugar islands. In 1731 Governor Joseph Talcott, the colony’s first native-born chief executive, reported that 44 vessels plied the West Indies trade carrying some 456 tons of goods. Within just 30 years, by 1762, the number of vessels increased to 76, carrying 6,790 tons. By the 1770s the number of ships had quadrupled, and the tonnage multiplied 20-fold. Connecticut couldn’t resist the sweet profits.

On January 4, 1771, Captain Dudley Saltonstall sailed the schooner Fox to the islands. The hold was packed with Connecticut fish, beef, pork, cheese, corn, oats, and Wethersfield onions. One might think that the West Indies could have produced their own food products, both produce and livestock, and that was true. Yet sugar was so valuable, island planters covered every tillable acre with cane. It was far more profitable to sell the granulated gold and simply pay for food and all sorts of other items than to take up even a small parcel of land for food production.

According to Eric Kimball in his 2009 doctoral dissertation “An Essential Link in a Vast Chain: New England and the West Indies Trade, 1700-1775” (University of Pittsburgh), Saltonstall’s variety of foodstuffs was accompanied by sawn boards and other wood products, such as house shingles. On deck were 14 horses and 11 oxen. The livestock accounted for 59 percent of the entire cargo’s value; by far, however, horses fetched the greatest price, at 46 percent of the cargo’s worth. Nor was it simple to transport live animals, all of which stayed on deck during a voyage. Cows and horses were often hoisted aboard using a special sling.

Just three years later, in 1774, Governor Jonathan Trumbull declared, “The Principal Trade of this colony is to the West India Islands.” Connecticut ships traded with British, French, and Dutch islands, carrying every manner of product in exchange for molasses, cocoa, sugar, and salt. The Colony boasted 180 vessels carrying 10,317 tons, all operated, as the governor noted, by “seafaring men.” The opportunity for profit was so great that it shifted the colony’s production toward a more market-oriented economy, one in which farmers and other businessmen specialized in specific items. Historian Bruce Daniels, in

New England Nation: The Country the Puritans Built (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), notes that “commercial farming grew because of the vast markets in the West Indies for Connecticut’s products.”

To fully understand the scope of Connecticut’s West Indies trade, historians turn to the only complete set of data for the colonial period: “Inspector General’s Customs Reports, 1768-1772.” Joseph Avitable, in “The Atlantic World Economy and Colonial Connecticut” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester, 2009) and Eric Kimball have engaged in painstaking studies that focus on the extent of Connecticut’s merchant endeavors. Kimball, in particular, has proven that the West Indies were by far the largest and most significant export market for ships clearing New Haven and New London, the two principal ports of the colony. Between 1768 and 1772, 444 vessels departed New Haven for the islands, representing 43 percent of the total number. Other vessels leaving the port engaged mainly in coastal trading with neighboring colonies. The West Indies-bound ships carried 18,090 tons of goods, which accounted for 56 percent of the tonnage of all trading vessels departing New Haven.

During the same period, New London was even busier, with 792 ships carrying 30,175 tons sailing south for the West Indies. As with New Haven, this traffic represented the single largest destination, some 42 percent of the total and 56 percent of the tonnage. Kimball notes that almost as much tonnage left New London bound for the West Indies as every port of destination served by all departing New Haven ships combined. Nor was it a one-way exchange; Connecticut needed its sweets.

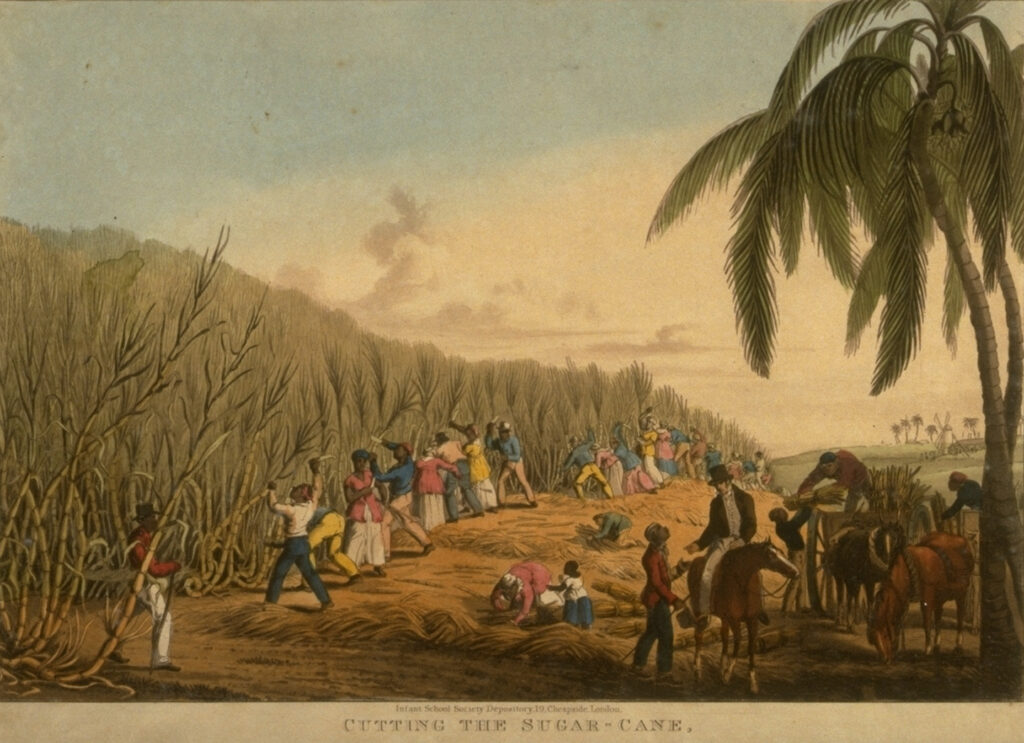

“A representation of the sugar-cane and the art of making sugar,” from the Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, ca. 1770. Nearly-naked enslaved people are shown working in the harsh conditions of the mills. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The import markets into the colony were dominated by three areas: the West Indies, New York, and Massachusetts, which together accounted for 93 percent of all vessels entering Connecticut. The latter two were considered coastal trades and by far the easiest of the three. Sailing to and from the islands presented a longer and potentially more harrowing journey, but it also offered far greater profits. Of the 993 ships that entered New Haven between 1768 and 1772, 407 (47 percent) came from the West Indies. New York accounted for 343 (34 percent) and Massachusetts 189 (19 percent). The vessels arriving from the islands carried 16,699 tons, some 54 percent of all tonnage entering the port. New London’s imports, like her exports, were even larger. Of the 1,710 ships arriving in the port during the 1768-1772 period, 567 came from the West Indies, carrying 25,391 tons of goods, or 46 percent of all the tonnage into the port.

While the aggregate numbers are remarkable and speak to Connecticut’s massive trade with the West Indies in the late colonial period, equally telling are the types and amounts of goods that made their way to the Caribbean. Again, the custom records from 1768-1772 tell the story.

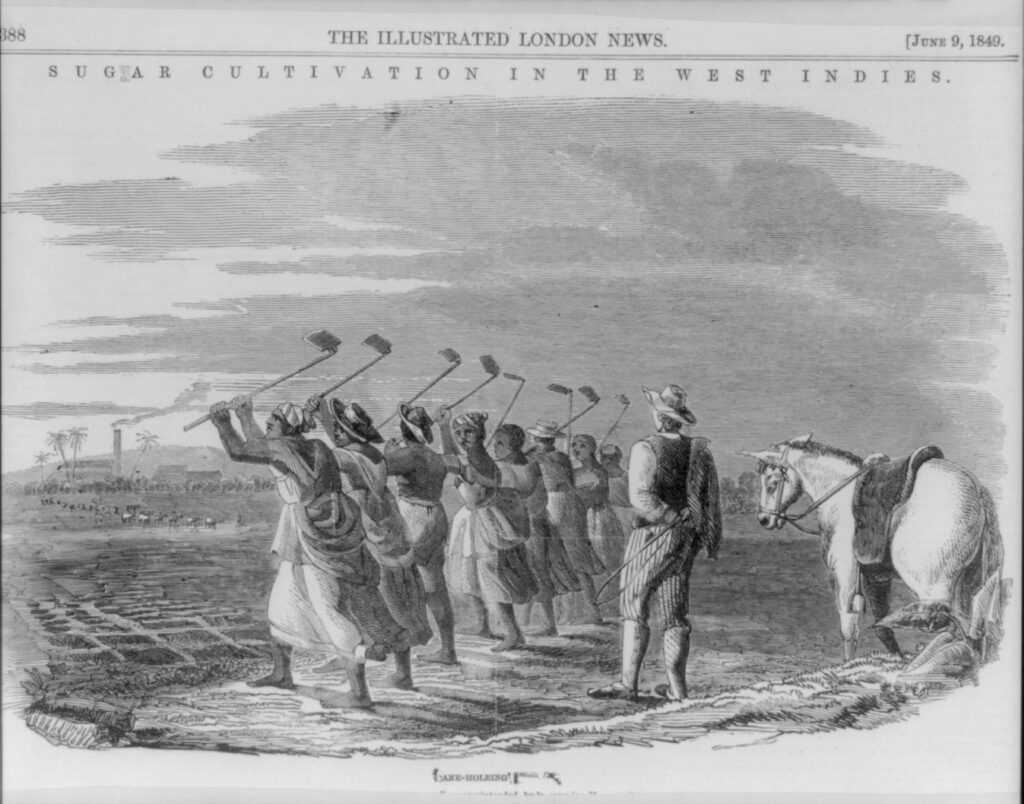

Line of enslaved people hoeing sugar cane in the field in the West Indies. The overseer wields a whip. image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The farmers of Connecticut shipped 44,546 pounds of butter, 122,596 pounds of cheese, and 74,470 pounds of tallow, used for making candles. More popular than cheese were onions, an item for which Wethersfield became well known, with its famed onion maidens, “who weeded and wept.” During this age of West Indian shipping, Connecticut exported 482,922 bunches of onions weighing 1,931,688 pounds. The genus allium became such an important trade item that the colony’s general assembly passed during this period a law entitled “An Act for regulating the Market and ascertaining the Weight of Bunches of Onions,” requiring that a bunch must weigh at least four and a half pounds and was required to be “cured, dry, well and firmly bunched.” Those who failed to adhere to either standard forfeited either the onions or their value. Additional food items included Indian corn, peas, oats, and apples, among others.

Animals, both livestock and slaughtered, also constituted important Connecticut exports. Vessels delivered 27,003 sheep, which were used for food and their dung for fertilizer. This accounted for almost half, 46.6 percent, of the entire number of sheep shipped from all of British North America between 1768 and 1772. Connecticut was also the leading supplier of cattle. Three of every four head came from the colony, with a total of 12,674, making up 73.7 percent of cattle exports to the West Indies. Also packed on Connecticut ships were 20,513 barrels of butchered beef and pork, each barrel weighing approximately 220 pounds, or 4,512,860 pounds of meat. Chickens by the tens of thousands also made the journey. Counted in dozens, New Haven shipped out 4,596, while New London sent 4,508. By the dozen, that’s 109,248 chickens cackling their way to the Caribbean.

Wood and building products were also highly valuable. Barrels made mass shipping possible in the colonial era and beyond. Producing barrel staves and the metal rings that held them together required skilled coopers, who expertly crafted the staves and fit them together for a water-tight seal. The abundant trees throughout the Connecticut River Valley kept sawyers busy making 6,957,304 staves and 5,821,199 wooden shingles that graced everything from island churches and rum distilleries to waterfront shops and plantation mansions. Nor were these the only building materials produced by the colony. Connecticut exports also included 2,145,187 feet of pine boards and 431,997 feet of oak planks. Shipping to a maritime region also necessitated 85,392 feet of oars. Then there were bricks, 1,184,950 of them. Connecticut products fed and built much of the West Indies, and sometimes adorned the homes of sugar merchants. Records show that a variety of furniture items sailed south, as did some 3,237 pounds of feathers, likely used in beds and pillows.

1769 Horses beinghoisted off Spanish Ships. “Embarcadero de los Cavallos” (1769) Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, BerkeleyBy far the most valuable commodity sent from Connecticut to Caribbean islands were horses, which accounted for 59 percent of the total value of all goods shipped between 1768 and 1772. Customs records reveal that three out of every four horses arrived from Connecticut. The total number is rather astounding, at 21,709, which amounted to 74.1 percent of all horses shipped from North America. The next closest colony in numbers was Rhode Island, with a paltry 3,290 horses.

Another set of records shows that between December 5, 1772 and January 1, 1774, 1,067 horses were imported to Barbados. Connecticut’s equine contribution during this 13-month period was 991, accounting for 93 percent of the total. Every commodity arriving to the islands had to be transported inland, and that required horse-power. Some were also used to turn the mills that crushed the sugar cane so that the juices could be rendered into granules, molasses, and rum. The finer breeds were prized by plantation owners as symbols of status and wealth.

While the mass of Connecticut farmers focused primarily on maintaining their families, with a bit extra for sale to the market, the vastness of the West Indies trade encouraged specialized markets for both the growth and production of foodstuffs and for collecting the many goods so that they could be exported through New Haven and New London. The network required to amass the assortment of Connecticut goods for shipment to the islands was remarkable. The agricultural items, horses, cattle, sheep, and other commodities weren’t produced by any one farm in mass quantities, so merchant middlemen honed the skills necessary to collect animals and products from throughout Connecticut and other portions of New England.

Governor Jonathan Trumbull, whose papers are housed at the Connecticut Historical Society, boasted about the colony’s connection to the Caribbean and detailed his own involvement in the trade. Historians know that he hired men to drive cattle and that he employed at various times during the year butchers to slaughter and pack meat. The reality, however, is that scholars understand very little about how or who managed these massive markets. As official port records, customs documents provide researchers with minute accounts of all items coming and going from Connecticut shores. The same sorts of precision paperwork simply don’t exist for the merchants who cobbled together resources by the tons and brought them in creaky wagons on bad roads or floated them down our many rivers to New Haven and New London, along with other ports. What is certain, though, is that early on, Connecticut entrepreneurs recognized and built upon the opportunities that the West Indies offered for profit.

Governor Jonathan Trumbull, whose papers are housed at the Connecticut Historical Society, boasted about the colony’s connection to the Caribbean and detailed his own involvement in the trade. Historians know that he hired men to drive cattle and that he employed at various times during the year butchers to slaughter and pack meat. The reality, however, is that scholars understand very little about how or who managed these massive markets. As official port records, customs documents provide researchers with minute accounts of all items coming and going from Connecticut shores. The same sorts of precision paperwork simply don’t exist for the merchants who cobbled together resources by the tons and brought them in creaky wagons on bad roads or floated them down our many rivers to New Haven and New London, along with other ports. What is certain, though, is that early on, Connecticut entrepreneurs recognized and built upon the opportunities that the West Indies offered for profit.

Yet there existed in all this monied trade a terrible cavity, a shady element to the sugar business that soured the entire affair: slavery. The fields and mills of the Caribbean were worked by African peoples stolen from their homes, placed in shackles, and delivered upon the shores of West Indian islands and, farther north, to the British-American colonies. The infamous Middle Passage was just one angle of the Triangle Trade that exchanged forced enslavement for the production of raw materials in the Americas and the trade of finished goods from Europe. These constituted the other two sides of the triangle. Because Connecticut was at the heart of the West Indies trade, the little colony was also heavily invested in this much more bitter affair.

Even before commerce with the Caribbean and African slavery escalated to what it became in the 18th century, the scions of Connecticut Puritanism were most willing to cast undesirables into bondage. The very first record of the colony’s West Indian trade in human beings came with the Pequot War, just after Connecticut’s founding, when at least 17 members of the tribe were enslaved and sent to Providence Island off the coast of South America. As Connecticut’s investment in the sugar trade increased over the next 150 years, so too did its commitment to slavery. Sugar and slavery, sweet and sour, were inextricably bound to one another.

In 1774 future president John Adams wrote that Boston’s “commerce has been an essential link in a vast chain, which has made New England what it is, the southern provinces what they are, and the African trade what that is, to say no more.” In that same year the Connecticut census listed more than 5,000 enslaved people living in the colony. Almost every city recorded at least a few slaves. Connecticut-built and Connecticut-owned ships ferried the enslaved, though no comprehensive study has revealed the full extent of the colony’s involvement. Anne Farrow’s revelatory book, Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery, published by Ballantine Books in 2007, explored some of this history, but there’s more work to be done by historians. My own work, Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice and Survival, published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011, told the story of the colony’s and, later, the state’s abundant anti-Black racial history and animosity to abolition. Connecticut didn’t rid itself of the noxious institution of slavery until 1784, with a gradual emancipation law, and didn’t fully exculpate the state from slavery until 1848.

Perhaps most ironic is that Connecticut’s ability to support the American Revolution was directly tied to the colony’s insatiable desire for sugar, all that was involved in procuring it, and the profits that flowed as a result. Long known as “the Provision State” because of its role in feeding George Washington’s army, Connecticut was able to achieve that status only because of the vast network of producers and merchants that had been developed to feed and supply the West Indies trade. In this sense, our own freedom was purchased through the commercial system developed to feed our sugar addiction and our dependence on the inexecrable institution of slavery.

Matthew Warshauer is a professor of history at Central Connecticut State University. He is the author of four books and numerous articles. He blogs at The Mindful Professor.org.