By Dave Corrigan and Karen Hudkins

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

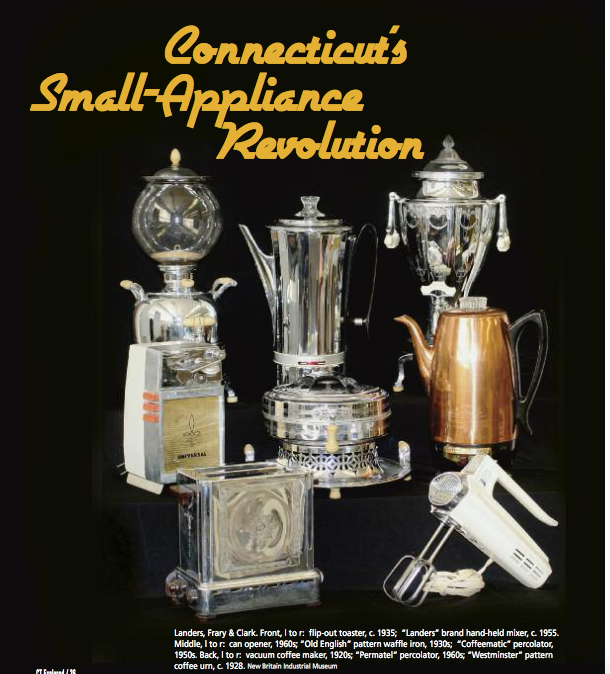

Connecticut has long been known as the manufacturing epicenter of many products, notably clocks, typewriters and firearms. Not so well known is the fact that from around 1910 until the 1970s, The Land of Steady Habits was home to nearly a dozen nationally recognized companies that developed, manufactured, and effectively marketed an array of electrical appliances that contributed to a revolution in the way Americans prepared food. These firms produced the small appliances—mixers, toasters, coffee percolators, and waffle irons, for example—integral to the preparation of food in the kitchens and at the tables of the slowly increasing number of electrified middle-class households. Although a few manufacturers produced large appliances, such as electric ranges, Connecticut’s main contribution was small appliances.

Aggressive advertising campaigns eventually convinced Americans that electrical appliances were necessities rather than novelties. With electricity more commonly available from the 1930s on, product lines expanded to include blenders, sandwich grills, and toaster ovens—their desirability enhanced and maintained by a succession of new styles and continued advertising. Ultimately, Connecticut appliance manufacturing declined as long-established companies such as Manning-Bowman of Meriden and Landers, Frary & Clark of New Britain disappeared through corporate mergers. The General Electric Co., established in Bridgeport in 1920, gradually moved its appliance manufacturing to plants in other parts of the country, and smaller firms, such as The Fitzgerald Co. of Torrington and Winsted, slowly faded from the scene.

Electricity Comes to Connecticut

The origin and growth of Connecticut’s electrical appliance industry went hand-in-hand with the growth of the state’s electric companies. In April 1881 the Connecticut legislature chartered companies in Hartford, New Haven, Norwich, Stamford, and New London to generate and sell electricity. These companies initially provided power for street lights and commercial use.

Electricity slowly made its way across the state. In 1910 The Hartford Electric Light Co. had nearly 1,000 customers, including some homes and tenements. Two years later the annual report of Connecticut’s Public Utilities Commission, established in 1911 listed 27 electric companies. Still, by 1918 the commission reported that only 612 square miles of the state (12 percent) was being served by electric companies, but that this covered “…all the cities and the more populous towns and communities.”

Making the Case for Electrical Appliances

In an effort to promote increased electrical consumption, not to mention profits, as early as 1914, The Hartford Electric Company offered THERMAX brand toasters, made by Landers, Frary & Clark of New Britain, at a reduced cost to its customers. But, as historian Glenn Weaver noted in The Hartford Electric Light Company (The Hartford Electric Light Co., 1969), “…the full impact of electricity in the home was not to be felt until the post-World War I decades.” Before the war wealthier households were “the ones least likely to electrify their kitchens,” he notes, since servants were still readily available and “the well-to-do were little inclined” to provide servants with labor-saving electrical appliances. “At the other end of the economic scale were those who could afford only the minimum electrical consumption of a few overhead lights in the most-used rooms.” Weaver noted that therefore “…the revolution in domestic living was taking place in the dwellings of the moderately well-off, middle-income families….” A 1920 advertisement by Landers, Frary & Clark, whose extensive lines of electrical and non-electrical household devices were emblazoned with the “UNIVERSAL” name—or “The Trade Mark Known in Every Home”—urged homemakers to “Universalize Your Home” by purchasing and using its products, referred to as Home Needs, so that “Housewives Need Not Worry Over the Servant Problem.”

Making Appliances Convenient to Use

Thomas Edison’s 1880 patent of an incandescent electric light bulb is the best-known milestone in the electrical history of America, and it played a significant role in the development of the electrical appliance industry. Electrical service first came to American households in the form of pendant lights hanging from the ceilings in rooms previously illuminated by gas fixtures. Electrical appliances in the early 1900s came equipped with a long cord with a screw-in plug at the end, similar to the base of a light bulb. To use the appliance, the light bulb had to be unscrewed and the appliance cord screwed in. This required someone to climb up on a chair or ladder to reach the ceiling-mounted light fixture and connect the appliance. The inconvenience and potential danger of this situation were slowly remedied by the invention and development of plugs and outlets, many of the earliest being invented and patented by Harvey Hubbell of Bridgeport. By the 1920s, “convenience outlets,” the now-ubiquitous baseboard and wall outlets, began to proliferate, and appliances began to be provided with the corresponding plugs to make the connections. In January 1922 the Perry Electric Co. of Hartford advertisement in The Hartford Courant offered “A Good Suggestion Right Now: Have a convenience outlet installed for those electrical appliances.”

In 1925 the Merchandise Division of the General Electric Co. of Bridgeport published a booklet titled “The Home of a Hundred Comforts,” which extolled the virtues of electricity in the home. It suggested that older houses could be economically retrofitted with electrical service and that new homes should be fully wired during construction, and that either option would add to the potential resale value of a home. The booklet noted, “A complete wiring system provides for all the electric lights … and for the appliances that you or a future occupant of your house may someday want to use.”

While a host of Connecticut companies produced various types of electrical appliances from 1910 to the 1970s, only four maintained product lines that encompassed most, if not all, of the kitchen appliances that homeowners of 1925 and their successors would “someday want to use” and that revolutionized food preparation in the first half of the 20th century.

Landers, Frary & Clark, New Britain

Advertisement, Landers Frary & Clark, highlighting their popular Colonial Revival “Lafayette” pattern, Pictorial Review, December 1928. Museum of Connecticut History

New Britain’s iconic manufacturing company was formed in 1862 with the merger of two companies making small metal hardware items and, for the next century, manufactured an enormous variety of products. According to appliance historian Earl Lifshey in The Housewares Story (National Housewares Mfrs. Association, 1973), these included “electric ranges, kitchen scales and vacuum bottles, window hardware and ice skates, mouse traps and percolators, can openers, cutlery and aluminum cookware … sausage stuffers, screw eyes and strap hooks, door handles and floor scrapers … cast iron match boxes and curry combs…” along with their famous “UNIVERSAL” bread makers and food choppers.

With the death of Charles S. Landers in 1900, 41-year-old Charles F. Smith became president of the company. It was the beginning of a new century and the dawning of a new era—an era ushered in on an electric wire. William T. Sloper, son of LF&C board member Andrew Jackson Sloper, recounted in The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson Sloper (Sloper, 1949) that by 1902 Smith, confident in his talent and business ability, had decided “he was not going to be satisfied to drone along in their little old cutlery business for the rest of his life: he would expand the business by entering the then comparatively new household electrical appliance field.”

The company was, of course, more than some “old cutlery business” and had been manufacturing a number of items, such as percolators and chafing dishes heated by alcohol burners. All that was needed now was to electrify them, a step made possible by a 1908 patent for an “electric heating vessel” (basically the company’s standard urn with an electric element added) assigned to the company by its inventor, Alonzo Warner of New Britain. By 1912 the company seized the opportunity offered by generous reductions in electricity rates to fully embrace the manufacture of electrical appliances. To maintain quality and control of the components, the company produced those as well.

Thus began an extended period of growth in product development, manufacture, and design. There were few aspects of domestic life that Landers did not produce an appliance for, and by the 1920s it was reported that Universal products could be found in one out of six American homes. In their 1945 publication “Forward March to Market,” Landers, Fray & Clark stated that there were 50 million Universal devices in use world-wide.

In 1957 the 15 millionth Coffeematic-brand coffee percolator rolled off the production line in New Britain. This tremendous achievement was celebrated by the creation of a version crafted from 40 troy ounces of 14-karat gold studded with 250 diamonds of various sizes and 150 rubies; the percolator and was insured for $50,000. After a presentation in New Britain, the gold Coffeematic made an appearance on The Today Show and was displayed at G. Fox & Co. in Hartford for a month before being exhibited around the country for a year.

In 1964 the company made its last important innovation. After spending $500,000 on research and development and $1 million on production equipment, Landers introduced what it claimed to be the first new coffeemaker in 20 years, the “Permatel.” A unique manufacturing process resulted in a pure nickel electroformed coffeemaker with a seamless body and a mirror-like finish. But a year later, new management decided that the company was a money-losing proposition, and the electrical appliance manufacturing segment was eventually purchased by General Electric, which then reaped the profits of LF&C’s revolutionary Permatel process.

Manning-Bowman Co., Meriden

The Manning-Bowman Co., formed in 1864 in Cromwell, manufactured Britannia ware, planished tinware, and porcelain enamelware. In 1872 the company merged with the Meriden Britannia Co. and moved to Meriden, where it remained for nearly 70 years. The company catered to hotels and restaurants, supplying a variety of cooking utensils. Its earliest venture in producing electrical appliances in the early 1900s was via the electrification of its line of alcohol-burning appliances. Before World War I, Manning-Bowman and Landers, Frary & Clark emerged as leaders in the electrical-appliance industry, positions they would maintain for many years.

Manning-Bowman products were well designed and high in quality, and the company kept abreast of style changes in the early 20th century. The company claimed to have pioneered the application of the non-tarnishing chromium finish to electric table appliances and to have introduced the concept of “matched appliances,” which were sets of appliances—typically a coffee service, toaster, waffle iron, cooker, and a percolator—all executed in the same style. In 1935 the “Pioneer Pattern” was introduced, joining the already popular “Harmony Pattern.”

In 1941 Manning-Bowman was purchased by the Bersted Manufacturing Co. of Chicago, a company known for producing cheaply made appliances selling for a fraction of the price of those made by Manning-Bowman. That led to the lowering of the quality of Manning-Bowman appliances. In 1948 the McGraw-Edison Co. of Elgin, Illinois purchased the Bersted company and continued to use the Manning-Bowman brand name until the mid-1950s.

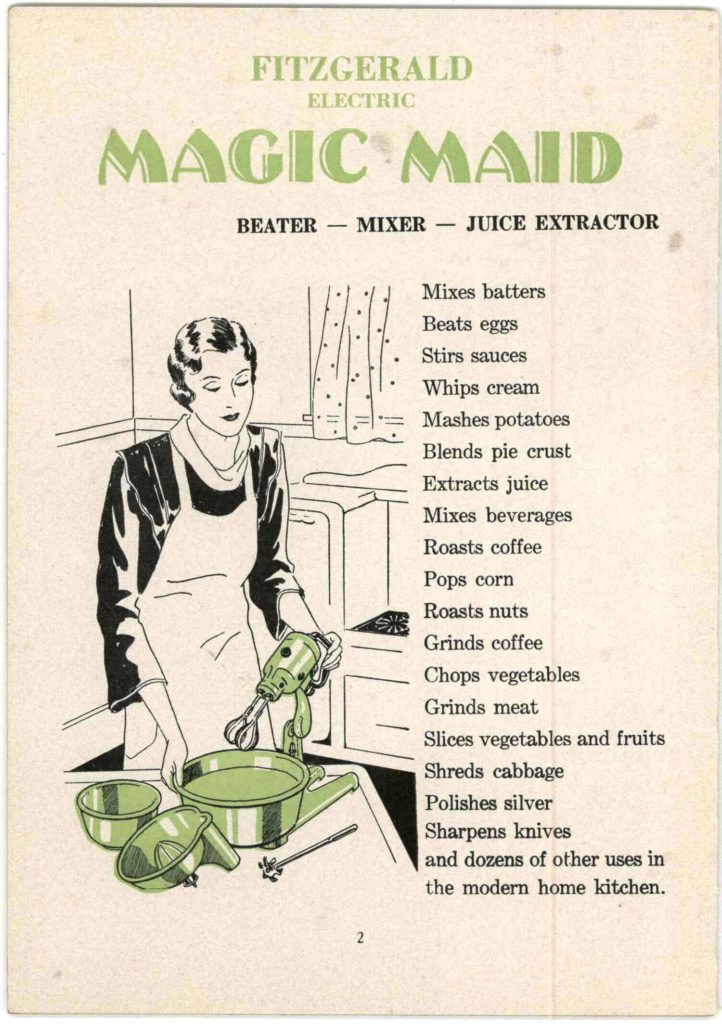

The Fitzgerald Mfg. Co., Torrington and Winsted

In 1893, 14-year-old Patrick J. Fitzgerald and his brothers Martin and Maurice emigrated with their family from Tipperary, Ireland to Waterbury. By 1898 the family had moved to Torrington, where Patrick became a machinist’s apprentice at the Coe Brass Co. In 1906 he founded the Fitzgerald Mfg. Co. in Torrington, supplying “Never-Leak”-brand engine gaskets to the fledgling automobile industry. From the beginning, it was a family business, with his brothers involved in running the company.

The gasket business prospered. The Fitzgerald company built a new factory in Torrington and acquired the former T.C. Richards Hardware Co. factory in Winsted in 1916. The company expanded into a second growth industry when it began manufacturing an electrical vibrator/massager around 1919 and an electric dishwasher in 1920. By the mid-1920s gaskets were being manufactured in the Torrington plant, while the Winsted facility was wholly devoted to electrical appliances—mixers, toasters, hot plates, sandwich grills, waffle irons, and coffee urns and percolators. On September 18, 1935 The Torrington Register reported that the company’s “electrical appliance line, nationally known under the trade names ‘Magic Maid’ and ‘Star-Rite,’ as well and favorably known to the American housewife.” The company’s appliances were priced at the medium-to-low end of the appliance market, and their advertisements often were aimed at newly-married couples.

Although it weathered the Great Depression and World War II restrictions on the manufacture of electrical appliances, by 1947 the company was transformed. It no longer marked its electrical appliances with the name “The Fitzgerald Mfg. Co.,” reserving that for the Torrington-made gaskets and auto accessories. A much-diminished appliance line, consisting of toasters, frying pans and grills, was manufactured under the names “Son-Chief Electrics Co.” and “Connecticut Appliance Co.” Both companies were located at the Meadow Street factory in Winsted, and Patrick J. Fitzgerald remained president of both, with brothers Maurice and Martin also listed as company executives.

Upon Patrick J. Fitzgerald’s death 1961, his son Donal became president of both Son-Chief Electrics and Connecticut Appliance. By 1976 production had become limited to a table-top grill manufactured by the renamed “Son-Chief Black Angus Co.,” and the Connecticut Appliance Co. had ceased to exist. In 1977 The Fitzgerald Mfg. Co. passed out of family control and the last vestige of Fitzgerald-made electrical appliances succumbed in the mid-1980s.

General Electric Co., Bridgeport

In 1920 the General Electric Co. of Schenectady, New York purchased the mammoth Bridgeport factory recently vacated by the Remington Arms-Union Metallic Cartridge Co. Remington built the factory in 1915-1916 and manufactured 1 million rifles and 100 million rounds of ammunition under a contract with Czarist Russia in the early days of World War I. The factory’s nearly 1.5 million square feet were quickly given over to the manufacture of large and small electrical appliances and electrical supplies such as wire, switches, and conduit. By 1940 GE had moved its headquarters to the Bridgeport facility and, through the 1960s, many of its 6,000 to 8,000 employees were engaged in the manufacture of irons, toasters, roasters, coffeemakers, mixers, waffle irons, and sandwich grills. Production of these small appliances, part of GE’s Housewares Division, continued unabated until the mid-1970s, when most of the company’s divisions were relocated from the out-dated Bridgeport factory into more modern, but out-of-state, plants.

Like clocks and typewriters, electrical appliances are no longer components of Connecticut’s manufacturing landscape. Like its Hartford counterparts the Royal and Underwood typewriter factories, the massive General Electric plant in Bridgeport has recently fallen to the wrecker’s ball. Many of the products fabricated in such factories survive and are highly prized by museums and private collectors as testimony to the innovative design and manufacturing expertise of the thousands of Connecticut workers who produced them. As further testimony to their skills and pride of craftsmanship, many of the appliances they made still work.

Dave Corrigan is curator of the Museum of Connecticut History and a frequent contributor to Connecticut Explored. His last story was “The Connecticut National Guard on the Mexican Border” (Spring 2017).

Karen Hudkins is museum director of the New Britain Industrial Museum. Hear her talk about the New Britain Industrial Museum, episode 2 of Grating the Nutmeg.

Explore!

Museum of Connecticut History

231 Capitol Avenue, Hartford

860-757-6535, museumofcthistory.org

New Britain Industrial Museum

59 West Main Street, New Britain

nbindustrial.org, 860-832-8654

Read more about Connecticut-made small appliances and cocktail accessories:

The Depression Gave Us–the Buffet Server?

The Gaiety of the Connecticut Cocktail Shaker

and on our Made in Connecticut TOPICS page