By Gene Leach

(c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

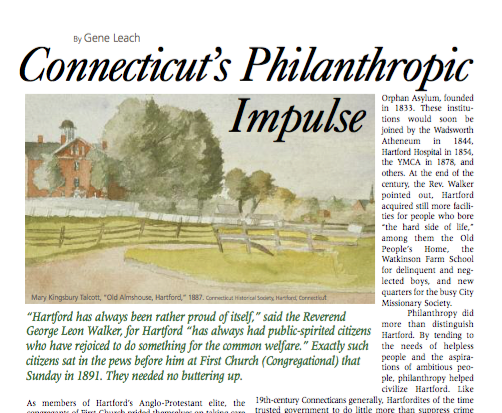

“Hartford has always been rather proud of itself,” said the Reverend George Leon Walker, for Hartford “has always had public-spirited citizens who have rejoiced to do something for the common welfare.” Exactly such citizens sat in the pews before him at First Church (Congregational) that Sunday in 1891. They needed no buttering up. As members of Hartford’s Anglo-Protestant elite, the congregants of First Church prided themselves on taking care of the town their ancestors had founded. But it was apt for their pastor to bless their benefactions because they thought of philanthropy as a Christian as well as a civic duty, as historian Andrew Walsh has noted in For Our City’s Welfare: Building a Protestant Establishment in Late-Nineteenth Century Hartford (Harvard University Ph.D. dissertation, 1995).

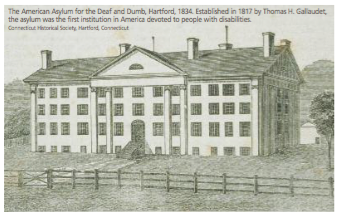

As early as 1835, another Congregational minister, Joel Hawes, boasted that “In acts of public and private charity” Hartford was “not surpassed by any place of equal population in the country.” As evidence, he could point to this smallish city’s institutions that were established to care for the less fortunate: the Asylum for the Deaf, founded in 1817, the Retreat for the Insane, founded in 1821, and the Hartford Orphan Asylum, founded in 1833. These institutions would soon be joined by the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1844, Hartford Hospital in 1854, the YMCA in 1878, and others. At the end of the century, the Rev. Walker pointed out, Hartford acquired still more facilities for people who bore “the hard side of life,” among them the Old People’s Home, the Watkinson Farm School for delinquent and neglected boys, and new quarters for the busy City Missionary Society.

Philanthropy did more than distinguish Hartford. By tending to the needs of helpless people and the aspirations of ambitious people, philanthropy helped civilize Hartford. Like 19th-century Connecticans generally, Hartfordites of the time trusted government to do little more than suppress crime and operate schools. Efforts to heal and improve residents’ lives were left predominantly to private benevolence. The city did take responsibility for relieving the very poor, but, when hard times in the late 1880s put hundreds in the municipal almshouse and thousands more on relief, angry taxpayers insisted that officials trim excesses of “public charity.” Private charity took up the slack, as it long continued to do. “The presence of so many philanthropic societies explains in great part the comparatively small cost of the outside poor to the city government,” the Hartford Times happily reported on November 12, 1911.

Philanthropy did more than distinguish Hartford. By tending to the needs of helpless people and the aspirations of ambitious people, philanthropy helped civilize Hartford. Like 19th-century Connecticans generally, Hartfordites of the time trusted government to do little more than suppress crime and operate schools. Efforts to heal and improve residents’ lives were left predominantly to private benevolence. The city did take responsibility for relieving the very poor, but, when hard times in the late 1880s put hundreds in the municipal almshouse and thousands more on relief, angry taxpayers insisted that officials trim excesses of “public charity.” Private charity took up the slack, as it long continued to do. “The presence of so many philanthropic societies explains in great part the comparatively small cost of the outside poor to the city government,” the Hartford Times happily reported on November 12, 1911.

Philanthropy also subtly democratized Hartford by enabling disempowered groups—non-Protestants, women, people of color—to play modest roles in public affairs. Anglo-Protestant white men gave to the needy in part to justify their monopoly on political power. By bettering other people’s lives they could prove they were the “best people,” a common phrase of the day, and therefore the fittest leaders.

Whether or not Hartford’s wealthy white Protestant men were its best people, they were not the only people who gave money and time for the public good. Non-Protestants, women, and people of color gave too, and by their giving demonstrated their own fitness to govern. Thus many groups contributed to a dense and diverse landscape of philanthropy in Hartford. The imposing “monuments of benevolence” built by the Protestant elite were only its most conspicuous features.

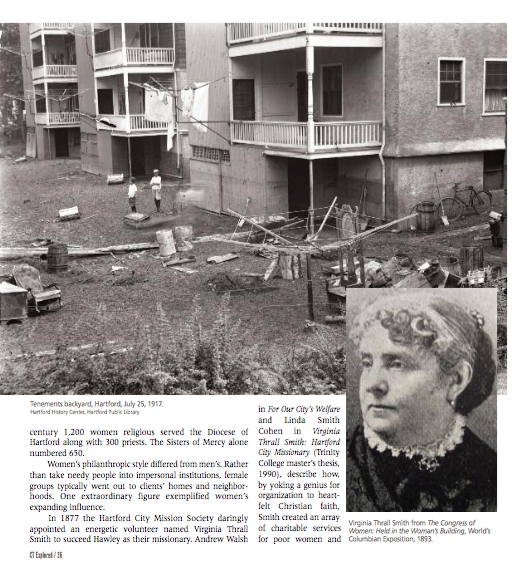

The city’s neediest people were hundreds of African Americans, residents since colonial times, and immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, arriving by many thousands in the second half of the 19th century. Increasingly all of these groups crowded into rickety tenement buildings along the Connecticut River (the “East Side”). They found work in Hartford, but few of the jobs available to them paid enough to lift them out of poverty. They made up for the meagerness of their resources by sharing them: bringing food to the hard-up family next door, loaning money to a man out of work, minding the children of a working mother. When neighborly philanthropy did not go far enough, poor Hartfordites looked to their own religious communities for help.

Weary of being set apart in established churches, African Americans began worshipping separately in a room of First Church in 1819. In 1826 they formed their own African Religious Society, from which emerged Hartford’s Fifth Congregational Church, with its sanctuary on Talcott Street, in 1833. Three years later black Methodists built an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on Elm Street. The new churches immediately went about improving educational opportunities for African American children. An 1830 petition to the state legislature complained that black children suffered discrimination in the public schools, which resulted in the creation of separate schools in each of Hartford’s African American churches. Relying on state funds as well as on donations by black and white churches, these schools counted among their teachers the brilliant pastor of Talcott Street Church, Rev. James W. C. Pennington, the poet Ann Plato, and other remarkable figures. Churches sponsored schools and other vital services for African Americans in New Haven and Bridgeport too, according to David O. White in “The Real Life of James Mars,” Connecticut History 43 (Spring 2004) and Katherine Harris and Stacey Close, African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

A torrent of Jewish refugees fleeing the Russian Empire in the late 19th century at first disconcerted Hartford’s well-established German Jews, but quickly each group began building accommodations for its booming population, according to David Dalin and Jonathan Rosenbaum in Making a Life, Building a Community (Holmes & Meier, 1997). A Ladies Sick Benefit Association formed in 1898 and opened the Hebrew Ladies Old People’s Home in 1907. [See story, page 42.] Another group of Eastern European women founded the Hebrew Ladies Orphan Asylum in 1912. Also in that year more than two dozen Jewish groups formed an umbrella agency called United Jewish Charities. Mount Sinai Hospital, the crowning creation of Hartford Jewish philanthropy, opened in 1923.

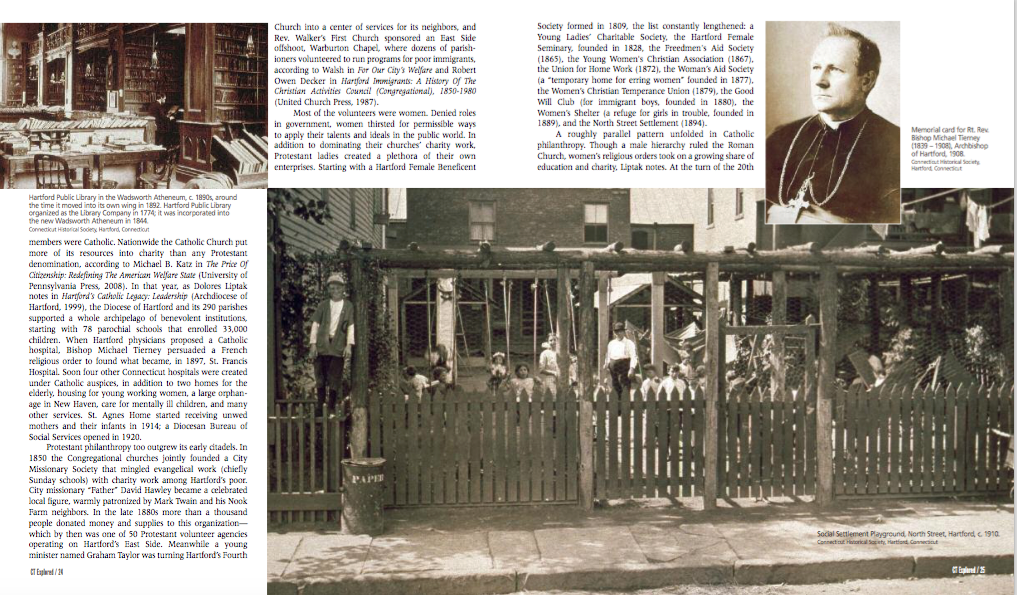

Even more extensive was Catholic benevolence, as might be expected in a state where by 1910 60 percent of all church members were Catholic. Nationwide the Catholic Church put more of its resources into charity than any Protestant denomination, according to Michael B. Katz in The Price Of Citizenship: Redefining The American Welfare State (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008). In that year, as Dolores Liptak notes in Hartford’s Catholic Legacy: Leadership (Archdiocese of Hartford, 1999), the Diocese of Hartford and its 290 parishes supported a whole archipelago of benevolent institutions, starting with 78 parochial schools that enrolled 33,000 children. When Hartford physicians proposed a Catholic hospital, Bishop Michael Tierney persuaded a French religious order to found what became, in 1897, St. Francis Hospital. Soon four other Connecticut hospitals were created under Catholic auspices, in addition to two homes for the elderly, housing for young working women, a large orphanage in New Haven, care for mentally ill children, and many other services. St. Agnes Home started receiving unwed mothers and their infants in 1914; a Diocesan Bureau of Social Services opened in 1920.

Protestant philanthropy too outgrew its early citadels. In 1850 the Congregational churches jointly founded a City Missionary Society that mingled evangelical work (chiefly Sunday schools) with charity work among Hartford’s poor. City missionary “Father” David Hawley became a celebrated local figure, warmly patronized by Mark Twain and his Nook Farm neighbors. In the late 1880s more than a thousand people donated money and supplies to this organization—which by then was one of 50 Protestant volunteer agencies operating on Hartford’s East Side. Meanwhile a young minister named Graham Taylor was turning Hartford’s Fourth Church into a center of services for its neighbors, and Rev. Walker’s First Church sponsored an East Side offshoot, Warburton Chapel, where dozens of parishioners volunteered to run programs for poor immigrants, according to Walsh in For Our City’s Welfare and Robert Owen Decker in Hartford Immigrants: A History Of The Christian Activities Council (Congregational), 1850-1980 (United Church Press, 1987).

Protestant philanthropy too outgrew its early citadels. In 1850 the Congregational churches jointly founded a City Missionary Society that mingled evangelical work (chiefly Sunday schools) with charity work among Hartford’s poor. City missionary “Father” David Hawley became a celebrated local figure, warmly patronized by Mark Twain and his Nook Farm neighbors. In the late 1880s more than a thousand people donated money and supplies to this organization—which by then was one of 50 Protestant volunteer agencies operating on Hartford’s East Side. Meanwhile a young minister named Graham Taylor was turning Hartford’s Fourth Church into a center of services for its neighbors, and Rev. Walker’s First Church sponsored an East Side offshoot, Warburton Chapel, where dozens of parishioners volunteered to run programs for poor immigrants, according to Walsh in For Our City’s Welfare and Robert Owen Decker in Hartford Immigrants: A History Of The Christian Activities Council (Congregational), 1850-1980 (United Church Press, 1987).

Most of the volunteers were women. Denied roles in government, women thirsted for permissible ways to apply their talents and ideals in the public world. In addition to dominating their churches’ charity work, Protestant ladies created a plethora of their own enterprises. Starting with a Hartford Female Beneficent Society formed in 1809, the list constantly lengthened: a Young Ladies’ Charitable Society, the Hartford Female Seminary, founded in 1828, the Freedmen’s Aid Society (1865), the Young Women’s Christian Association (1867), the Union for Home Work (1872), the Woman’s Aid Society (a “temporary home for erring women” founded in 1877), the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (1879), the Good Will Club (for immigrant boys, founded in 1880), the Women’s Shelter (a refuge for girls in trouble, founded in 1889), and the North Street Settlement (1894).

A roughly parallel pattern unfolded in Catholic philanthropy. Though a male hierarchy ruled the Roman Church, women’s religious orders took on a growing share of education and charity, Liptak notes. At the turn of the 20th century 1,200 women religious served the Diocese of Hartford along with 300 priests. The Sisters of Mercy alone numbered 650.

Women’s philanthropic style differed from men’s. Rather than take needy people into impersonal institutions, female groups typically went out to clients’ homes and neighborhoods. One extraordinary figure exemplified women’s expanding influence.

In 1877 the Hartford City Mission Society daringly appointed an energetic volunteer named Virginia Thrall Smith to succeed Hawley as their missionary. Andrew Walsh in For Our City’s Welfare and Linda Smith Cohen in Virginia Thrall Smith: Hartford City Missionary (Trinity College master’s thesis, 1990), describe how, by yoking a genius for organization to heartfelt Christian faith, Smith created an array of charitable services for poor women and children: loans for distressed households, day care for working mothers, visiting nurses, and an emergency shelter. To promote “better understanding between helpers and helped,” Smith wrote in 1879, “We must go to them; they will not, cannot, come to us. Christianity consists not more in keeping ourselves up than in helping others up.” Inspired by Smith’s leadership, Hartford women formed an auxiliary City Mission Association that eventually furnished Smith with 125 volunteers and one-third of her budget.

Smith also pushed philanthropy into alliance with social reform. From her work she realized that the needs of unwed mothers and their children were far greater than private agents alone could handle. The solution demanded the authority and resources of the state. In 1884 Smith persuaded the Connecticut General Assembly to end the practice of dumping children of unwed mothers in almshouses. As Walsh notes, during its first eight years a new system of placing children in private foster care (often arranged by Smith) took in 2,237 children, most of whom ended up in “respectable families.”

When Smith’s zeal ran afoul of established authorities and public opinion, a backlash cut short her career as city missionary in 1892. Within a decade, however, history began to catch up with Smith’s activism. The lion’s share of Connecticut giving would continue to be motivated by the altruism of individuals, as it still is today. (The latest available figures from the National Philanthropic Trust and the Connecticut Council for Philanthropy show that individuals account for more than 70 percent of all giving in the United States, and almost a third of all donations go to religious organizations.) But gradually principles promoted by progressive reformers at the turn of the 20th century altered philanthropy almost as much as they altered government. As long as government took no responsibility for the general welfare, private relief of distress could do no more than patch up society. In the 20th century philanthropy would increasingly try to forestall distress by “challenging, reforming, and renewing society,” acting not in place of government but in collaboration with it, according to Joel L. Fleishman in The Foundation: A Great American Secret (Public Affairs, 2007).

When Smith’s zeal ran afoul of established authorities and public opinion, a backlash cut short her career as city missionary in 1892. Within a decade, however, history began to catch up with Smith’s activism. The lion’s share of Connecticut giving would continue to be motivated by the altruism of individuals, as it still is today. (The latest available figures from the National Philanthropic Trust and the Connecticut Council for Philanthropy show that individuals account for more than 70 percent of all giving in the United States, and almost a third of all donations go to religious organizations.) But gradually principles promoted by progressive reformers at the turn of the 20th century altered philanthropy almost as much as they altered government. As long as government took no responsibility for the general welfare, private relief of distress could do no more than patch up society. In the 20th century philanthropy would increasingly try to forestall distress by “challenging, reforming, and renewing society,” acting not in place of government but in collaboration with it, according to Joel L. Fleishman in The Foundation: A Great American Secret (Public Affairs, 2007).

A new kind of organism, the nonprofit foundation, emerged to implement the new thrust in philanthropic work. The original foundations were set up to distribute the immense fortunes of men such as Russell Sage (1907) and Andrew Carnegie (1911). Soon, however, “community foundations” were gathering gifts from multiple sources to aid the residents of a given area. In their focus on local needs these organizations resembled 19th-century benevolent societies, except that community foundations were nonsectarian, they gave out grants instead of volunteers and supplies, and their grant-making procedures made for far-sightedness and objectivity.

Cleveland formed the first community foundation in 1914. The first in Connecticut appeared in Waterbury in 1923 (now the Connecticut Community Foundation), followed by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving (HFPG) in 1925. By the 1980s every Connecticut town fell within the granting orbit of one of these entities.

Though Connecticut community foundations vary widely in scale of assets and grants, the biggest being HFPG and the Community Foundation for Greater New Haven, they share broad patterns. Like churches and benevolent societies before them, all these groups have specialized in supporting social, medical, and educational services. But following the example set by the young HFPG, they have seldom given “direct relief” to needy people, and they have shied away from covering grantees’ regular operating expenses. They have preferred to fund “exploratory or pioneering” projects that launch new services or improve the delivery of established ones, according to Glenn Weaver in Hartford Foundation For Public Giving: The First Fifty Years (HFPG, 1975).

The civil rights movements and urban unrest of the 1960s spurred community foundations to diversify their boards and update their priorities. Historian Barbara Donahue, in her 75th-anniversary history of the Hartford Foundation (HFPG, 1999), describes a surge of HFPG grant-making for the Community Renewal Team, the Urban League, the Blue Hills Civic Association, and other groups working to serve and empower people of color in Hartford. Today most of the state’s community foundations continue to cultivate “Civic Vitality” (the Greater New Haven foundation) and “Community and Economic Development” (the Connecticut Community Foundation), and almost all of them have established major grant lines for the arts, women’s needs, and environmental protection, too.

“True Godliness don’t turn men out of the World, but enables them to live better in it, and excites their Endeavors to Mend it,” said America’s first great altruist, William Penn. During the past two centuries Connecticut philanthropists have amended Penn’s credo, growing steadily less religious and more bureaucratic, but they have held to the heart of it. They assume world-mending is endless; there are many ways to go about it, and there are no master menders.

Eugene Leach is professor of history and American studies emeritus at Trinity College and a member of the Connecticut Explored editorial team and board.

Explore!

“The Victorian Philanthropy of John Fox Slater and William Albert Slater,” Fall 2021

“The Handkerchief Brigade,” Fall 2015