By Mary M. Donohue with Kory Mills (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

By Mary M. Donohue with Kory Mills (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

Steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie was both reviled as the enemy of the working man and known as the “Patron Saint of Libraries.” Between 1881 and 1919 he funded the construction of 2,509 libraries throughout the English-speaking world, including 1,679 in the United States, according to George Bobinski in Carnegie Libraries, Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development (American Library Association, 1969).

Carnegie revolutionized the process of making steel by managing production from the ownership of the required raw materials to the railroads that shipped the finished product. But this vertical integration came at a price to workers. The Carnegie Steel Company experienced turbulent relations with its labor force, culminating in the violence of the Homestead Strike of 1892, a strike that broke steelworkers’ unionization attempts and depressed workers’ salaries.

Theodore Jones, in Carnegie Libraries Across America, A Public Library (Preservation Press, 1997), describes Carnegie’s belief that a man should spend the first half of his life accumulating wealth and the last half giving it away. Carnegie published his views in 1889 in a two-part essay “Wealth,” later published in 1900 in book form as The Gospel of Wealth. “As Carnegie saw it, wealth was a responsibility placed in his hands to oversee for public good, and he intended to be a ‘scientific philanthropist’…His most repeated line was: ‘The man who dies thus rich, dies disgraced.’”

Carnegie funded his first library in1881 in his Scottish hometown of Dunfermline. That was soon followed by library buildings in Pennsylvania, where Carnegie Steel was based. Bobinski suggests that Carnegie’s interest in libraries might have gone back to his father’s deep respect for books and his own pleasure as a young working boy using the J. Anderson Library of Allegheny City on Saturday afternoons. Carnegie began what he termed his “wholesale” period of library philanthropy in 1898.

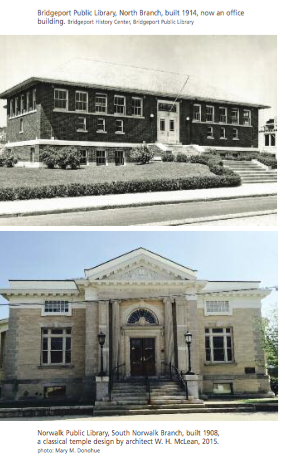

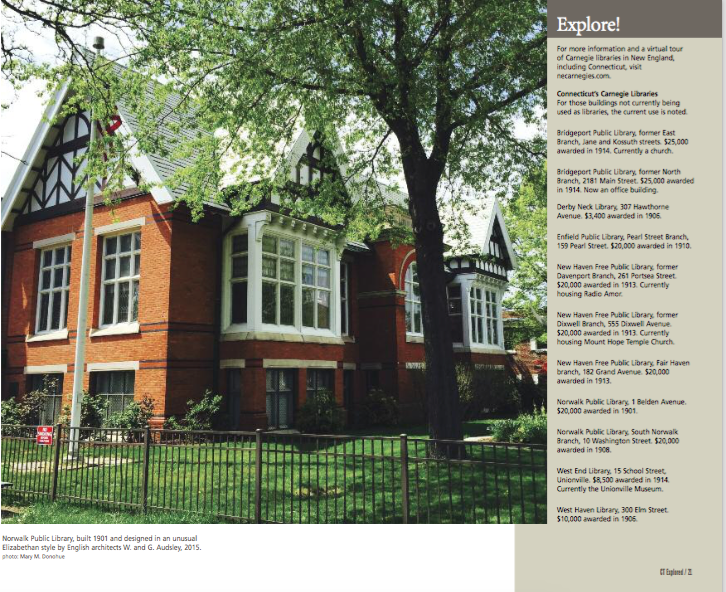

Because New England had by this time well-established public libraries and public schools, the region has fewer Carnegie libraries than other parts of the country, Bobinski notes. Still, Connecticut has 11, primarily in towns that in the early 20th century had industrial districts with rapidly growing populations of workers. [See Explore! for a complete list.] Carnegie was a firm believer in the value of branch libraries to serve the working class in their neighborhoods, and 5 of Connecticut’s Carnegie libraries are branches (2 in Bridgeport and 3 in New Haven). Three Connecticut communities applied for Carnegie library grants but were unsuccessful: as Bobinski reports, Darien’s residents voted it down, Deep River’s town council voted against the town’s support in perpetuity, and New Canaan was rejected by Carnegie for architectural design issues.

Because New England had by this time well-established public libraries and public schools, the region has fewer Carnegie libraries than other parts of the country, Bobinski notes. Still, Connecticut has 11, primarily in towns that in the early 20th century had industrial districts with rapidly growing populations of workers. [See Explore! for a complete list.] Carnegie was a firm believer in the value of branch libraries to serve the working class in their neighborhoods, and 5 of Connecticut’s Carnegie libraries are branches (2 in Bridgeport and 3 in New Haven). Three Connecticut communities applied for Carnegie library grants but were unsuccessful: as Bobinski reports, Darien’s residents voted it down, Deep River’s town council voted against the town’s support in perpetuity, and New Canaan was rejected by Carnegie for architectural design issues.

Applying for a Library Building

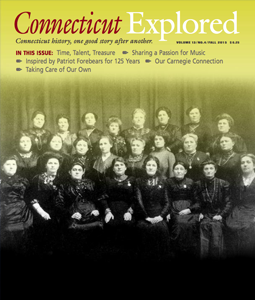

The criteria for selection included several simple but rigidly mandated requirements. Requests were only accepted from municipalities and towns with populations larger than 1,000. A “Schedule of Questions” was sent to each community that inquired about a library grant. Carnegie charged his private secretary, James Bertram (1872-1934), with reviewing requests and managing all of the details of the library program (which never had a formal name). Bertram estimated the cost of building a library at about $2 to $3 per resident. The building lot was provided by the town; the program only funded the construction of the building and required that the town commit to providing the equivalent of 10 percent of the Carnegie construction grant annually in perpetuity for operations, building maintenance, and purchase of books and furnishings.

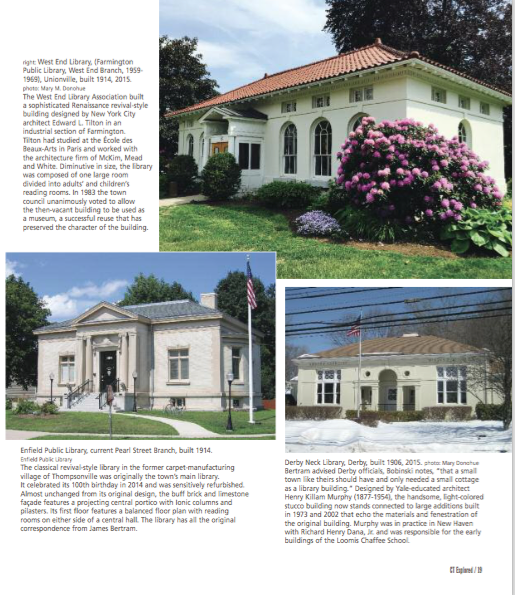

Although Carnegie libraries tend to be easily recognizable, Carnegie did not require that the buildings be named after him and did not demand a specific architectural style. According to Bobinski, Bertram began to request architectural plans after about 1908 and discouraged, and sometimes rejected, plans that wasted space and money on grandiose entrance halls or ostentatious domes. Successful applications had key elements in common: a high basement area containing a lecture hall, furnace room, restrooms, and work room and a first floor with abundant natural light, separate reading rooms for children and adults, a librarian’s desk for circulation, and the stacks. Bertram consulted top architects and produced a booklet of floor plans to help communities with their planning.

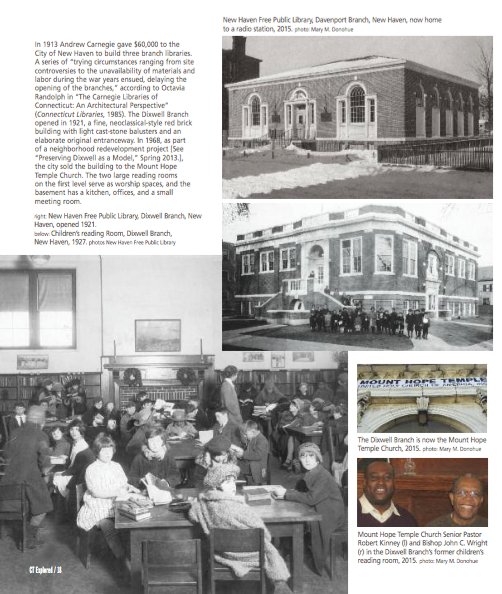

In 1915 the board of the Carnegie Corporation commissioned a study of the successes and challenges of the Carnegie-funded libraries. By then, public libraries had become an expected civic institution. When the Carnegie library fund program ended in 1919, Carnegie had donated more than $42 million to library construction. Today, all 11 of Connecticut’s Carnegie libraries remain standing. Six still serve as libraries, 2 now house churches (though one of these will return to its use as a library soon), 2 are used as office space, and 1 houses a local historical society museum. In addition, 5 of the library buildings have benefited from the Connecticut State Library’s construction grant program that provides funding for library expansions and improved accessibility, thus allowing the historic buildings to grow and serve modern needs.

Mary M. Donohue is an architectural historian and the assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored. Kory Mills, while a senior at Central Connecticut State University, served as a Connecticut Explored intern in Spring 2015.

Mary M. Donohue is an architectural historian and the assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored. Kory Mills, while a senior at Central Connecticut State University, served as a Connecticut Explored intern in Spring 2015.

Explore!

For more information and a virtual tour of Carnegie Libraries in New England, including Connecticut, visit necarnegies.com.