By Alan Owen Patterson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2008/2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Connecticut’s Blue Laws, those laws that today prohibit such things as liquor sales on Sundays, are as much a part of our state’s identity as nutmeg, brownstone, and Mark Twain. But just where did they come from, and where did they get their colorful name?

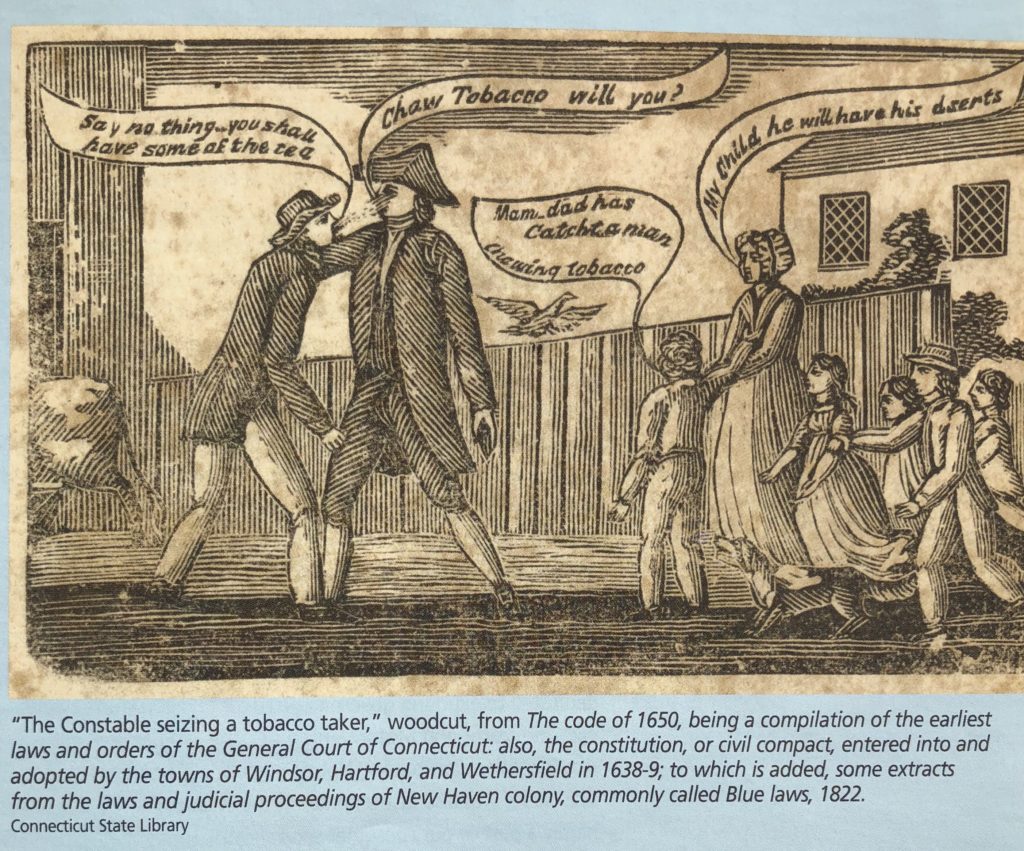

The term “Blue Laws” first appeared in a 1762 satirical pamphlet written by Reverend Noah Welles of Stamford. His use of the word “blue” is thought to refer to anything puritanical, rigid, prudish, or moralistic; it apparently did not, despite a long-held myth, derive from the color of the paper on which the pamphlet was printed. Welles set out to criticize the laws penned by Governor Theophilus Eaton and Reverend John Cotton of the New Haven Colony in 1655 that regulated behavior, guarded against personal moral offenses such as gambling and public drunkenness, and prohibited business from being conducted on the Sunday Sabbath. But while Welles may have coined the term, it was Connecticut crank Reverend Samuel Andrew Peters who gave it legs.

Born in Hebron, Connecticut in 1735, Peters became an Episcopal minister and loyalist sympathizer. Chased out of Connecticut by the Sons of Liberty in 1774 for his zealous efforts to thwart support for the Revolutionary War, he escaped to England. In retaliation, in 1781, Peters spitefully published The General History of Connecticut from Fenwick to Revolution, in which he created 46 outlandish axioms, passing them off as Connecticut’s law of the land. Peters’s exaggerations caused a stir in England as they comically misrepresented Connecticut colonists as dunderheads in need of ultra-repressive legislation. The Connecticut colonists, livid at this portrayal, outlawed the purchase and possession of Peters’s book in the colony.

Peters’s book forever muddled in people’s minds the distinction between actual laws and these fanciful ones. Peters’s “Blue Laws” often were taught in schools as historical fact.

By the 1800s, many laws regulating behavior and Sunday observances were facing repeal. In 1812 laws forbidding drovers, wagoners, teamsters, and sailing vessels from traveling on the Lord’s Day were repealed. In 1814, Connecticut repealed laws that forced citizens to pay a fine of 50 cents for failing to “apply themselves carefully to the duties of religion and piety on the Lord’s Day” and that made attendance at church compulsory. By 1838, Connecticut had also repealed laws against fining children for profanity on Sundays and the carrying of mail on that day.

Late in the 19th century Peters would again return to center stage as historians re-examined his contributions to Connecticut history. Just what had he intended in publishing his “Blue Laws,” and to what extent were his “laws” consistent with those actually on the books? In 1876, James Hammond Trumbull sorted the matter out in The True Blue-Laws of Connecticut and New Haven and the False Blue-Laws Invented by the Rev. Samuel Peters (Hartford: American Publishing Co., 1876).

Trumbull showed that, for example, Peters’s law #33, “Whosoever sets a fire in the woods, and it burns a house, shall suffer death,” exaggerated the punishment. The actual penalty from the Connecticut Colony was, “the payment of one and a half the damage, or in default of payment, corporal punishment at the discretion of the court.” Some of Peters’s laws were borrowed from other colonies and not found in any Connecticut code. Peters’s law #14 stated that “No food or lodging shall be afforded to a Quaker, Adamite, or other Heretic” with punishment “for the first and second offence with fines, and with death for the third.” There was nothing like this in the Connecticut Codes, but New York had such a law.

Trumbull’s exposé was published during a sweeping period of industrial and progressive social change. Interest again focused on laws of moral behavior and those concerning commercial activity on Sundays. In 1886, for example, New Haven residents could be fined $4 for attending Sunday concerts, while organizations could expect heavier fines for operating. The New Haven Opera House was warned against holding a series of sacred concerts on Sunday nights. German societies and the Good Samaritans, a temperance organization, both held meetings on Sundays and “livened proceedings with music.” Even as the temperance movement would be among the most vocal advocates for upholding the ban on the sale of liquor and tobacco on Sundays, they were nonetheless affected by the Puritan standards upheld by Connecticut legislation. While Sunday liquor and tobacco laws were strictly enforced, music on Sundays was tolerated, with most fines going uncollected by local governments.

As Trumbull’s book title suggests, at some point the term “Blue Laws” came into popular usage to stand for the Sunday laws. Today, Connecticut’s ban on Sunday sales of alcohol is usually referred to as a Blue Law [repealed in 2012]. Other Sunday or Blue Laws were modified or repealed as early as 1902 and as recently as 1979. In Caldor’s Inc. v. Bedding Barn, Inc. (1979), the State Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the law banning Sunday retail sales, concluding that “there was no rational connection between the items the legislature deemed appropriate to sell on a ‘day of rest’ and the establishments allowed to stay open to sell them.” Vestiges of the law remain, however.

Connecticut, despite having been stripped of all other Blue Laws from the colonial period, continues to uphold the tradition of banning Sunday alcohol sales. Many states had blue laws through the years, but today only 15 states ban alcohol sales on Sunday, with three states, including Connecticut, banning all alcohol (beer, wine, and liquor). While Samuel Peters could have never imaged the Connecticut we live in, a world of 24-hour news, all-night retail stores, and casinos, the history of the blue laws may be less a tale about a Connecticut crank seeking revenge on his home state than an opportunity to reflect on a question Albert Schweitzer raised (albeit in a different context): “What do we lose if Sunday becomes just like any other day?”

Alan Owen Patterson teaches social studies at Conard High School in West Hartford and interned with Connecticut Explored as a graduate student at CCSU.