(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

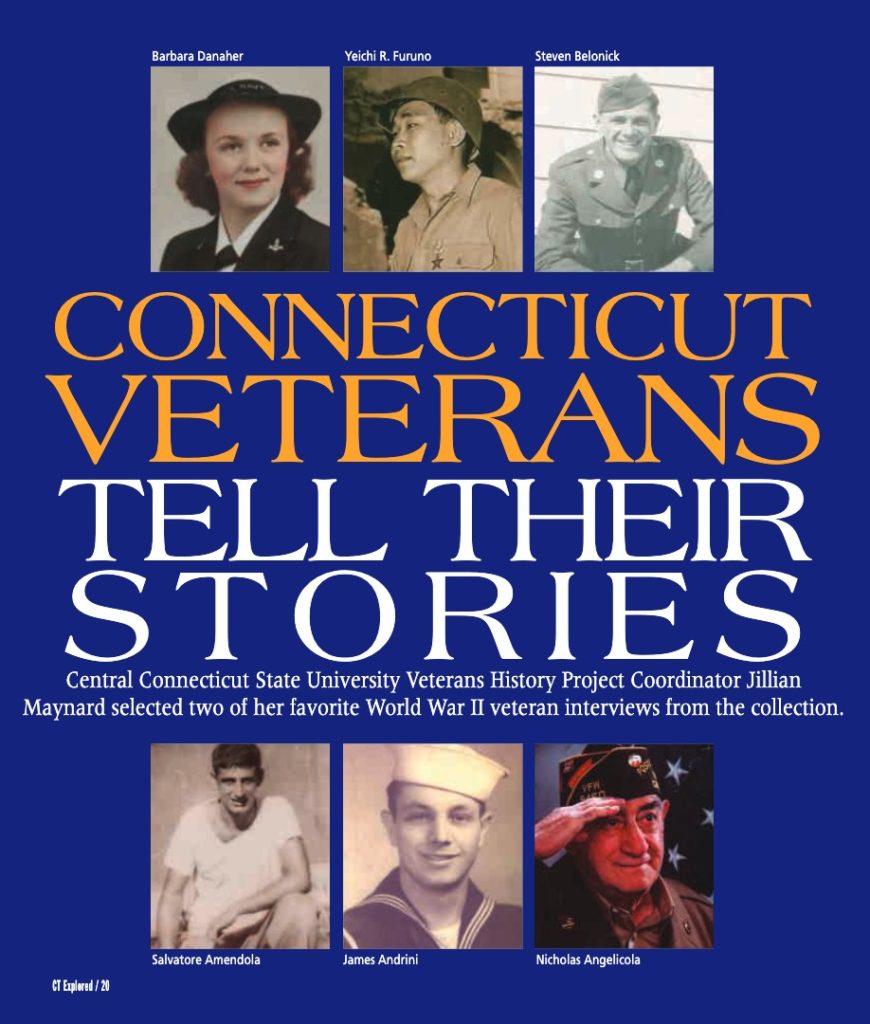

Veterans History Project Coordinator Jillian Maynard selected two of her favorite World War II veteran interviews from the collection.

Love and War: Val and Joan Santhouse

At the time of their interview in 2010, Valdemir (Val) and Joan Santhouse had been married for more than 60 years and had known each other since they were six years old. Like many young couples who faced uncertain futures during World War II, promises were exchanged in love letters written across the Atlantic and commitments made to stay together. They agreed “that whoever decided to leave [their marriage]would have to take the children!,” Val explained with a sly grin.

When the Naval Station Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, leading to the United States’s formal entry into the war, Val and Joan were a young, dating couple from New Jersey. In the interview, Joan remembered how “everyone came together, we were very somber, and supported the military.” For both Val and Joan, this meant military service.

On a visit to New York City with her mother, Joan enlisted in the U.S. Navy, a process that took just 10 minutes, she said. Boot camp began in August, and Joan recalled that it was “extremely hot, and extremely wet.” Billeted in an apartment building in the Bronx, Joan spent her days learning to march to and from the armory and taking classes in Naval procedures at Hunter College.

She was assigned to a role with the Fleet Post Office in New York City in conjunction with the U.S. Postal Service, where she was responsible for ensuring that mail to and from the soldiers overseas was properly distributed. Now living in a hotel in Manhattan, Joan and the other navy women enjoyed Broadway shows, courtesy of local donations, during their time off. The excitement of living in the city sat alongside the sobering reality of sifting through mail for overseas soldiers, some of whom would never make it home.

Joan was later assigned to the Philadelphia Naval Yard in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as a secretary. She recalled thinking that another city offered new adventures and a chance to be near her parents, who were stationed at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Many times, as she told her story, Joan would say that her time in the service was not difficult, given the opportunities afforded to her and the other women: living in new cities, taking in shows and other entertainment. However, during her service in Philadelphia she frequently witnessed the return of injured soldiers from the Pacific, which was a constant reminder of the chaos of the war and of Val, who was in the thick of it all.

Val’s father had been a soldier in World War I and had strong feelings against his son’s joining the military for yet another world war. There was little he could do, though, when Val was drafted. As a draftee, Val was able to choose a branch of service and decided on the U.S. Army. He became a T-5 technical driver in the 3rd Armored Division. His hope was to transfer to the U.S. Air Force. “I really wanted to fly,” he said, but he remained in the army for the duration of the war. Val entered the service officially on April 1, 1942. “April Fool’s Day,” he said, which Joan remarked was “an easy day to remember.” While in boot camp, he trained and learned to march, but he also took classes in demolition, an activity he described as learning how to blow things up, “which is fun and games when you’re young.”

Once in combat, serving in England, France, and primarily Cologne, Germany, Val’s job was to drive an M4 tank, maintain the equipment, and ensure that the tank was always loaded with the correct amount of explosives and ammunition. He and four other soldiers made up the crew, occupying tight quarters and uncomfortable temperatures. The tanks “were hot in the summer and cold in the winter,” he recalled, with little more than ambient air coming in past the engines. The constant noise of the running engine and the blasts of guns were largely responsible for Val’s hearing loss later in life.

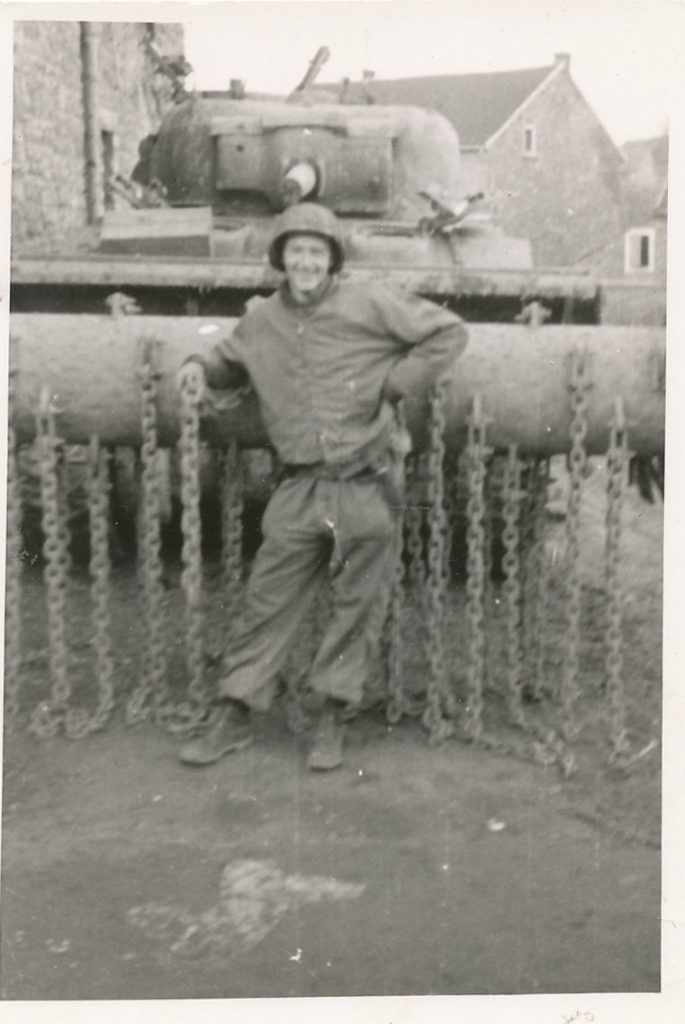

Valdemir Santhouse, Nordhausen, Germany during World War II. Courtesy of Val Santhouse, Veterans History Project, CCSU

Val liked to make his tanks go fast and was known to break off the “governor,” the mechanism that kept the tank to a maximum speed of around 24 miles per hour. Val decided, “I would be the governor,” and in doing so enabled the tank to reach nearly 40 miles per hour. He was also clever enough to devise a strategy for keeping the throttle in place with a pistol belt so that he could ride outside the tank and get some fresh air.

In one harrowing account, Val and his division were sent to take the city of Paderborn, Germany in the dead of night—a night he described as so dark he could not see his hand in front of his face. He used only his instinct to guide him down the hilly roads toward the city, pushing the tank to a tremendous speed. As they began descending a large hill, a gut feeling told him something was up ahead. A futile attempt to turn the tank did not prevent it from running into a German “Royal Tiger” or “Tiger II” tank, weighing about 70 tons. They bounced off the Tiger and rolled into a nearby ditch. The crew was knocked out. Surprisingly, the five soldiers were left alone by the Germans, who perhaps thought they were dead. Val and his crew came to and set off by foot until they found other Allied soldiers.

Frightening incidents such as this were why Val would bet against anyone uttering the phrase, “this damn war has got to be over.” Almost as if to tempt fate, Val “…bet against them, hoping to God I’d lose.”

Back on U.S. soil, Joan’s work with the navy and the Fleet Post Office gave her a unique understanding of how important mail could be for a soldier during the war. She wrote letters every day, especially to Val, who was not always able to write on a regular basis. Long periods would pass between his letters, which she said was always troubling to her.

But Val found ways to let Joan know he was okay. One Valentine’s Day, Joan walked back to her lodging in New York City to find her room filled with two-and-a-half-dozen roses in glass milk bottles, with blooms the size of teacups, she recalled. Val had contacted someone in the Red Cross in hopes of getting flowers to Joan. His message reached Mary Rockefeller, wife of Nelson Rockefeller (president of Chase National Bank and future U.S. Vice President), who cut the flowers from her personal greenhouse and had them delivered.

And so the war years passed and each served their time, doing their best to stay in touch. Joan kept in regular contact with Val’s mother, who worried about her son and the lack of regular letters from him.

At war’s end, Val and Joan were discharged and decided to go to school on the G.I. Bill (the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944). Joan’s family moved from New Jersey to Connecticut, and she attended the University of Connecticut. They spent a year “getting readjusted and getting to know each other again,” and then finally tied the knot in 1947. Val worked at Pratt & Whitney as an engineer for 35 years.

When they reflected on the war and their time in service in their 2010 interview, both Val and Joan were adamant that war is no place for young people, yet they understood the necessity of their service. They’d seen how history is doomed to repeat itself, which was never more obvious than when Val and Joan would visit injured soldiers, men and women, at their local V.A. hospital. Seven children and eight decades later, the Santhouses certainly found a way to make the most of life after war.

This story is based on the CCSU Veterans History Project interviews by Gary Burnett with Val and Joan Santhouse, September 10, 2010, archived in the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University.

Trailblazer Albert C. Stewart

Speaking softly into the camera, Albert (“Al”) C. Stewart revealed a small smile and a quiet laugh in portions of his interview with the Central Connecticut State University’s Veterans History Project.

Stewart recounted a journey to active service that was not as straightforward as most. Initially too young for the draft, as the war raged on in Europe and the Pacific, Stewart enrolled in the University of Chicago and pursued his studies. By the time his draft notice came in, he had been chosen to train as a weatherman for the Tuskegee Airmen, and his status was deferred for a year. Unfortunately, the exciting opportunity to join the Tuskegee Airmen fell through, and he went back on the draft list. Upon graduation, he secured a job with Sherwin-Williams paint company and waited. The call came in the early days of 1945—which, as it turned out, was the final year of the war.

In his March 2009 interview, Stewart described ending up in the U.S. Navy with a hint of nonchalance. “I just stamped my card ‘navy,’” he said. Traditionally a young man with a college degree who was drafted into the navy went immediately to midshipmen school—provided he was white. Stewart, as an African American draftee, was required to attend boot camp, and so he traveled to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. His arrival was not a “pleasant day,” he recalled with a slight chuckle. Though scores of white sailors were ushered through registration and given their barracks assignment, Stewart had to wait for enough black men to arrive to form a group. Due to their low numbers, this took the whole day—so long, in fact, that he complained to an authority about the wait, but to no avail. By the time he and a group of 39 other African American men reached their barracks, night had fallen.

Stewart did not remember boot camp as being particularly difficult. He was older than most of his fellow sailors, many of whom were still 18. He was already familiar with responsibility and hard work. The hour of 6 a.m. came quickly each morning, and he and his group would head out into the bitter cold of winter on Lake Michigan to run drills, learn to march, and participate in various exercise programs. Their days were full of classes. Stewart described jumping in with a quiet determination, and his effort did not go unnoticed. He was selected as Company Honor Man and deemed best in the crew.

Shortly after graduating as a Seaman 2nd Class, Stewart was approached about taking an exam to determine if he could join the officers’ training program. He was unaware that he would be among the first black officers on an integrated ship. He passed the entrance exam and joined 1,300 other midshipmen from around the country at the University of Notre Dame for U.S. Reserve Naval Midshipmen School. Stewart was the only black man among them. He found himself surrounded by white men, most from the eastern part of the country, and particularly the southeast. “That was 1945. Some just couldn’t imagine a black being there,” he remarked, and described it as an “individual effort” whether or not a fellow officer would talk to him. One of the few tense moments came during a game of touch football, during which some of the men tried to rough him up on the field. He remembered, with a slight smile, “I roughed them up instead.” Running between classes was a requirement for all the sailors, and one day when Stewart slowed to a walk, he was called out by name to keep running. He surmises that the only reason the man knew his name was because of his skin color.

Stewart completed the officers’ training program later that year. Japan had surrendered on August 15, effective September 2. The responsibilities of the navy and other branches of military service were slowly transitioning to recovery and peacetime. Upon graduation, Stewart and his fellow graduates attended the ritual ceremony in which their assignments were announced to the group amid cheers and applause. Being the only black officer, Stewart assumed he wouldn’t leave the United States, since those jobs were usually given to white officers. Much to his surprise, he was assigned to the AO-25 Sabine, a fleet oiler headed to the Pacific.

Late in August Stewart boarded a ship to Japan, and then sailed to Shanghai, China, where he boarded the Sabine. The shock of the officer on deck when he arrived was obvious, he said. “He couldn’t imagine a black officer.” But that surprise did not prevent the officer from being happy to see the replacements that would allow his current crew to finally return home after years of war.

Stewart became the 2nd Division Officer, responsible for the mid-ship-to-aft portion of the vessel. His division, along with the 1st and engineering divisions, took turns taking watch of the Sabine. When not on watch, they cleaned the ship and participated in exercise classes and other programs. Stewart was also the athletic officer, so he spent time devising exercise programs for the entire crew. The Sabine traveled the Pacific waters and refueled ships that were in the process of de-escalating remaining hostilities and transitioning to post-war activities.

Stewart talked about one older man on the ship who had served in the navy for 25 years and was not happy about Stewart’s being an officer. His constant commentary and spewed curses at Stewart made for an unpleasant day-to-day existence. Invoking a tradition by which navy sailors on the ship worked out their differences, Stewart invited the man to descend the long staircase down to the pump room to fight it out. When the man refused, thus ignoring the customs of the ship, Stewart effectively shut him up.

Stewart’s service with the navy continued aboard the Sabine for a year without shore leave. His dedication to his duties and steady leadership led to one of his happiest memories in the service. He was told by members of his crew that he was their favorite officer. At the end of his service, he returned to the University of Chicago. While there he met his wife, Colleen. Soon the couple traveled to St. Louis so that Stewart could pursue a Ph.D. in chemistry at St. Louis University. In 1951, he was the first black person to receive a doctoral degree in Missouri, “by 15 minutes!,” he said; another man earned a Ph.D. in sociology a few minutes later.

Besides his impressive career as a senior chemist with the Union Carbide Corporation, and a consultant for the Ford Foundation, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the Atomic Energy Commission, Stewart devoted much of the rest of his life to helping other black people find better opportunities. He was a part of various Urban League efforts to help working-class citizens find employment. After his retirement from Union Carbide, he taught at Western Connecticut State University, in the Ancell School of Business, of which he later became Dean.

Besides his impressive career as a senior chemist with the Union Carbide Corporation, and a consultant for the Ford Foundation, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the Atomic Energy Commission, Stewart devoted much of the rest of his life to helping other black people find better opportunities. He was a part of various Urban League efforts to help working-class citizens find employment. After his retirement from Union Carbide, he taught at Western Connecticut State University, in the Ancell School of Business, of which he later became Dean.

Service can mean a lot of things to people. Stewart said he believes that his service in the navy was the reason he’s been confident in taking chances his whole life. “Being in the military gave me a conviction that I could do a lot of things.”

This story is based on the CCSU Veterans History Project interviews by Jeanne Marie Christie with Albert C. Stewart, March 20, 2009, archived in the Veteran’s History Project at Central Connecticut State University.

Jillian Maynard is a reference & instruction librarian at Central Connecticut State University and helps oversee the CCSU branch of the Veterans History Project.

EXPLORE!

Receive each beautiful and informative issue! Subscribe Today!

Read more stories about Connecticut in World War II in the Fall 2020 issue and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.

Explore all of the Veterans History Project at CCSU interviews at web.ccsu.edu/vethistoryproject/.

View the Santhouses’ and Stewart’s full interviews at

Val Santhouse at youtu.be/CJF4vvysMZQ

Joan Santhouse at youtu.be/y4399fUIY9Q

Al Stewart at youtu.be/-FSvZfTMi-8

Read this earlier story from the Veteran’s History Project

“I Wanted to Fly: Connie Nappier,” Fall 2011