By Dawn C. Adiletta

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The cold was so intense that when I kept the [stove]…burning with all force I was still cold … [T]here was as you may imagine a great outcry for bedclothes … Every particle of bed clothing in the house is in use so that there is nothing to make a bed for anybody else unless I make up more comfortables … we of the house made up six in one day and put four pounds of cotton in each and now we want six more for company and extras.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe to her husband Calvin, December 27, 1850.

Writer Harriet Beecher Stowe was a firebrand when it came to her anti-slavery stance, but she was also passionate about hearth and home. During the particularly cold winter of 1850 Stowe struggled to heat her drafty Maine house (she would move to Hartford in 1864) and keep her young children warm. Just two days after Christmas, Stowe, her servant, and 14-year-old twin daughters were furiously stitching utilitarian bedcovers. Desperate for warmth, the women raced to produce “comfortables,” or what we today call comforters.

Most 19th century quilts probably were much like the quilts Stowe and her household hurriedly completed: utilitarian pieces, produced for warmth or basic comfort. But there were also remarkable exceptions. Before 1800, quilts were expensive luxury items, the most desirable of which were imported from England or France. Furthermore, throughout the 19th century, many women, and some men, took the time to design, create, or purchase decorative quilts that provided warmth for body and soul. This fall, The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center showcases some of these remarkable pieces in its newest exhibition, Unfolding History: Quilts from New England Collections.

A PATCHWORK OF QUILTS

The history of quilts and their makers offers a glimpse at the rich tapestry of life in early Connecticut. All true quilts share basic structural elements; they are frequently described as fabric sandwiches with a top, filling, and backing, held together by stitches. They vary widely, however, in shape, size, design, workmanship and value. Some quilts represent a significant investment of money or time. Some were produced to raise funds for charities, some as pieces of domestic art. Quilts were created to commemorate, honor, or please individuals; others were produced by anonymous workers for distant markets. Some were made to welcome new children, and some marked the death of a loved one.

Despite the persistence of stories about frugal colonial housewives recycling fabric scraps into patchwork quilts, people did not start making what we now know as patchwork quilts until the end of the 18th century, and patchwork quilts did not become common until the second quarter of the 19th century. Inventory studies of the pre-Revolutionary era consistently demonstrate the rarity of colonial-era quilts. A recent survey of New England probate records counted 1 quilt for every 55 blankets, 16 bedruggs (as the word was then spelled), and 16 coverlets. Quilts were also considerably more valuable than other bed-coverings. The average quilt’s value was 5 times that of a blanket and about 3 ½ times that of a bedrugg or coverlet.(1)

Since imported quilts were status symbols, colonial American women were eager to learn how to create less expensive versions for their own homes. By the 1720s, advertisements for quilting instructions began to appear in New England newspapers.(2) The lessons must have been successful, for diaries and account books suggest that by the Revolutionary War quilts in a typical New England home were as likely to be made at home from imported or domestic fabric as they were to be ready-made imports. But whether early quilts were imported or homemade, they were generally made of whole cloth.

Whole-cloth quilts are constructed by sewing together widths of the same fabric. Some whole-cloth quilts were made of silk or cotton, but most surviving 18th-century whole-cloth quilts are calamancoes. Calamancoes are made of worsted wool that has been quilted and then treated to have a glossy surface. The best calamancoes were calendered, or run between heated rollers that melted the surface of the wool and made it shine. Less expensive calamancoes, including those made in America, were pressed with heated iron plates to achieve the polished surface. Whole-cloth quilts derived their decorative value from their quilting designs, which might be as simple as a grid or include pomegranates, pineapples, hearts and flowers or feathery plumes.(3)

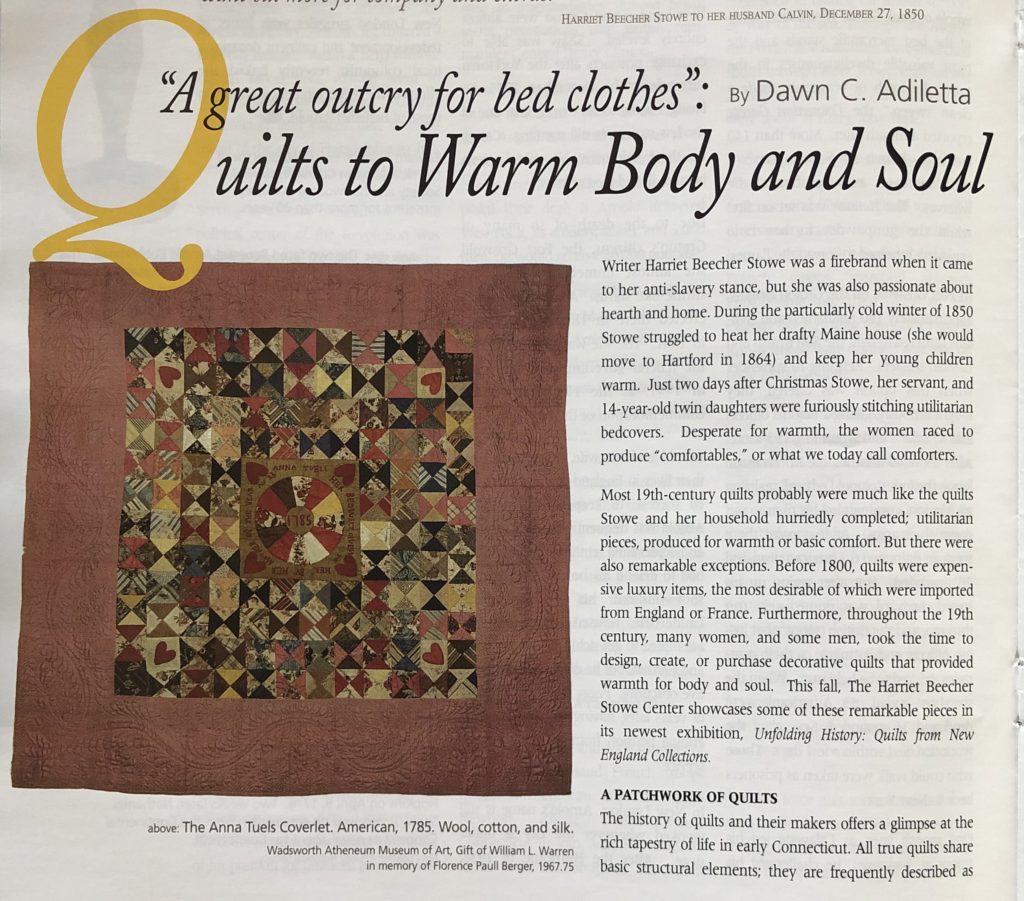

By the last quarter of the 18th century, as fabric began to become more affordable due to new water-powered textile mills, New Englanders began sewing together smaller pieces of fabric to create patterns. Some cut out design elements of printed chintz fabrics to applique them on to a plain fabric. Others stitched small squares, hexagons or diamonds together. Wills, newspapers, and letters all provide brief descriptions of early American patchwork quilts, but few examples remain. The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford owns what many believe to be the earliest documented American-made patchwork quilt. The 1785 Anna Tuel quilt is made of squares and triangles of wool, cotton, and silk.

By the 1820s and ‘30s, the Industrial Revolution and New England’s numerous textile mills made fabric very affordable. Quilt-makers grew bolder and more creative in their use of their material. Quilters no longer only used decorative elements from printed chintz to inspire applique designs. They also cut fabric to create flowers and other designs of their own.

QUILT-MAKING FOR FUN AND PROFIT

The diary of teenager Elizabeth Foote of Colchester, Connecticut provides insight into early American quilt-making but also challenges the assumption that all women made their own quilts. Elizabeth worked as a quilter and seamstress, sometimes hiring herself out. In between gossip about “sparking” couples and complaints about her sisters, Elizabeth included quilting references. In April 1775, only days before the battles of Lexington and Concord, she wrote, “I stay’d at home and spun & the Lady’s all went to Olive Foots Quilting.” The following day Elizabeth wrote “I went & work’d for Mrs. Kellogg all day & they had a Quilting but we all came home before dark.”(4)

Elizabeth also used her diary as an account book to record time and money owed to her, She noted when she worked for neighbors or exchanged labor with friends. She received payment for making and altering clothing and spinning yarn; she sold a woven coverlid and knapsack to outfit a soldier. Her careful notations suggest that Elizabeth may have considered her contributions to her neighbors’ quilts as employment:

June 7, 1775 – I went to Mr Pomroys to help them Quilt

June 8 – I came home from Mr Pomroys having done 2 days work there

Later that same year, Elizabeth wrote “- I did housework & drew a Quilt Border for Mrs. Blush.”(5)

Diaries like Elizabeth’s and others challenge our understanding of communal quilting parties. Did quilters always gather just as friends? Or because they owed each other a day’s work? Or because they were being paid to do so?

Elizabeth Foote may have been paid for her needlework, but there is little doubt that Candace Roberts of Bristol was more interested in the social aspects of quilt-making. Nineteen-year-old Candace earned her income by decorating tinware and painting clock faces. She loved parties and dancing, and quiltings provided another opportunity to gather with friends and neighbors.(6) Note that both Candace Roberts and Elizabeth Foote referred to quilt-making gatherings as “quiltings”; the term quilting “bee” came into use in the late 19th century.

Women diarists’ and professional writers’ accounts suggest that women created liens of support as they quilted together, sharing secrets of housekeeping and childrearing, discussing politics, slavery and abolition, and even womens’ rights. These writers also document the festivities that followed the work. In 1805 Candace wrote, “… went to a quilting at Capt. Manross’s. …Had a most delightful afternoon, and in the evening was very highly entertained with all kinds of company and most excellent music — returned home very late.”

EARLY 19TH-CENTURY FRIENDSHIP OR ALBUM QUILTS

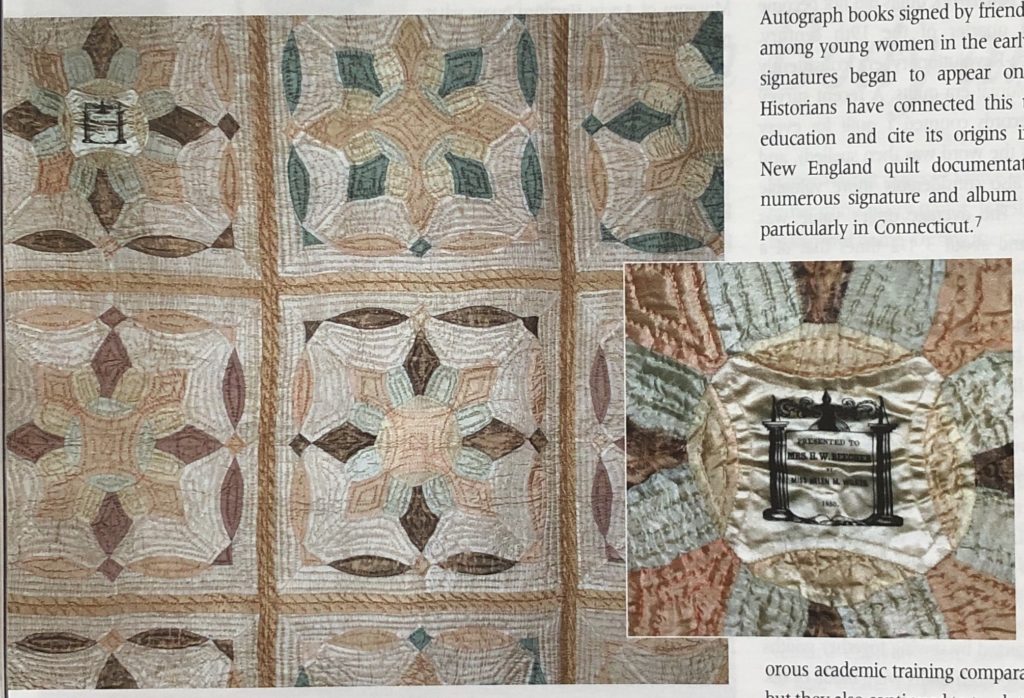

Autograph books signed by friends and family became popular among young women in the early 19th century, and collected signatures began to appear on quilts by the late 1830s. Historians have connected this type of quilt with women’s education and cite its origins in Delaware and Baltimore. New England quilt documentation projects have revealed numerous signature and album quilts in New England, too, particularly in Connecticut.(7)

Connecticut female academies were among the earliest in the nation and set the standard for those that followed. They included Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Academy and Catherine Beecher’s Hartford Female Seminary. Academies permitted young women to gather together, exchange ideas, and form friendships. The Academies offered rigorous academic training comparable to a college degree today, but they also continued to teach traditional “accomplishments” such as French, music, art, and sewing.(8) At Litchfield Academy students made quilts for the Female Benevolent Society and for “indigent students” at Andover Theological Seminary.(9)

Portion of a silk quilt owned by Eunice Beecher, wife of clergyman Henry Ward Beecher, pieced in Crown of Caesar pattern with presentation block. inset right: The presentation block reads “Presented to Mrs. H. W. Beecher by Miss Helen M. Wilkes 1850.” Miss Wilkes’s identity is unknown. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

The growing number of girls and young women who attended academies is reflected in the surging number of New England signature and friendship quilts.

Early signature and friendship quilts were made as farewell gifts or to mark special celebrations such as marriage. Since such quilts “served to preserve the memory of relationships,”(10) as historian Jessica Nicoll has remarked, some may have been made as personal keepsakes.

Signature quilts began to fade from fashion in the 1859s but returned as fundraiser quilts after the Civil War. In 1880, Harriet Beecher Stowe received a letter from the Illinois School for Girls, which was planning a bazaar. “Among other things of interest we are making an ‘Autograph Silk Quilt’ [including]names of prominent ladies and gentlemen of both Europe and America – Will you kindly assist us by sending us your Autograph?”(11)

MID-19TH CENTURY: QUILTS TO OFFER COMFORT

Quilts serve as physical reminders of women’s public efforts and private sentiments. Some quilts were raffled off to anonymous winners who treasured their prizes as symbols of such causes as anti-slavery or as emblems of their support of their church. Other quilts were shipped to foreign missions or to family members settling the west; those quilts served as tangible proof that the missionary or pioneer was not forgotten.

Traditions of raffling quilts to raise funds and sending quilts to distant missionaries found a new use during the Civil War. Working under the guidance of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, women augmented government supplies to the Army by sending shirts and socks, combs and court-plasters, and thousands of quilts. At least a quarter million quilts and comfortables were forwarded to troops during the war; more than 5,000 were sent from Hartford alone in 1863.(12)

Some women raided their own household bedding collections to support the war effort just as their grandmothers had done during the Revolutionary War. Others gathered to make new quilts.(13)

QUILTS FOR AN INDUSTRIAL AGE

Industry has long played an important part in the history of quilting by producing inexpensive goods that made it easier for quilters to acquire the necessary fabric, threads, needles, and pins. After the Civil War, however, factories began to manufacture quilts, too. In 1867, the Palmer Company of Montville began hiring people to make quilts and tied comforters. At first Palmer operated like a 17th-century quilt factory, ordering quilts from people who worked from home following the company’s manufacturing guidelines. This cottage industry provided welcome employment for civil war widows and badly injured veterans. Though hand quilting remained a slow process, the business flourished. In 1872, however, as the nation rose to the challenge of sending relief to the survivors of the Chicago fire, the Palmer Company received such a large quilt order that it shifted all its energy dinto quilt-making. The company developed machines capable of stitching 20 rows of quilting at once and produced nearly 10,000 comfortables during the following business year. The new process was faster, but the finished quilts were not as well made as those done by hand. Palmer’s better-quality quilts and comforters continued to be hand-done until 1884, when the Palmer Quilting Machine was invented.

THE LATE 19TH CENTURY: A MATTER OF TASTE

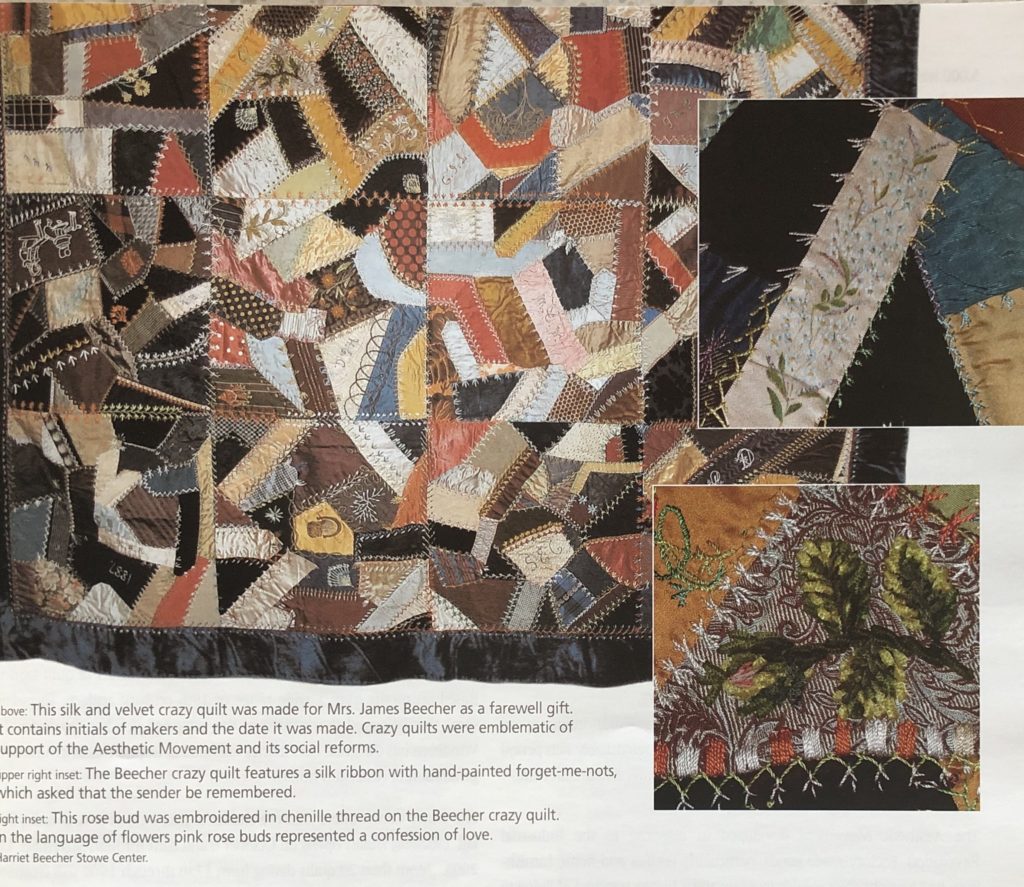

The Aesthetic Movement began to exert its significant influence on American decorative arts in the 1870’s, sparking a remarkably rich period of artistic activity in the fine arts — painting, sculpture, and architecture — and especially in the decorative arts.(14)

The Aesthetic Movement developed in response to the Industrial Revolution. Factory-made goods, particularly textiles and home furnishings, had brought great wealth to a few and a higher standard of living to many, but critics recognized that factories also contributed to unhealth housing and horrific abuses of child labor. Aesthetic Movement reformers also charged that factories sacrificed quality for quantity in their products.

Advocates of Aestheticism argued that appreciating art and beauty was the foundation of all decent human values. They believed that if society valued the work of craftsmen and artists, the lives of all individuals would be improved. At the heart of the Aesthetic Movement was the conviction that aesthetics, or good taste, could be taught. Formal schools were created to teach art and art appreciation, but the primary aesthetic classroom was the home. Since women were perceived as the main voice of domestic influence, they were targeted to promote this new ideology. Children could be taught to appreciate art through the clothing, furniture, and household decorations their mothers selected. The importance of decorative arts soared. “The home is the center of life,” one proponent remarked, “and if we can take art into the homes and then through the homes into the neighborhood, and then from one neighborhood into another, we shall soon make our whole city beautiful. (15)

In the midst of this new emphasis on the decorative arts came the crazy quilt. Crazy quilts are not truly quilts. Instead of the typical “fabric sandwich” that included a middle layer of batting, they are made by sewing randomly sized pieces of fabric, usually velvet or silk, directly to a square foundation cloth. The squares are then sewn together, decorated with ornamental stitches, and backed with a solid piece of fabric. By incorporating aesthetic symbols, the language of flowers, and personalized mementos crazy quilts become objects of art intended for display, not for use. Making a crazy quilt went beyond fashion. It was a matter of taste and a means to advocate for Aesthetic ideals and social reform.(16)

CREATING NEW TRADITIONS

Quilting remains a popular activity in Connecticut and across the nation; today more than 21 million Americans identify themselves as quilters.(17) This past spring, the Stowe Center launched a new venture that has already proven popular with quilters: a collection of quilt fabrics based on the Stowe Center’s collection called The American Woman’s Home Collection™. This new line of textiles is produced in association with Windham Fabrics, one of the nation’s top manufacturers of quilt fabrics. Based on motifs from a wide range of 19th-century artifacts, including some that belonged to members of the extended Beecher-Stowe family, Windham has designed new fabrics intended to inspire creativity in a new generation of American homes.

The Stowe Center offers visitors a chance to take a closer look at quilts this fall. Unfolding History opens on October 6 and runs through November 11, 2006. More than 20 quilts dating from 1750 through 1900 will illustrate the story of quilting’s stylistic evolutions and how those changes reflect womens’ shifting roles.

The Stowe Center offers visitors a chance to take a closer look at quilts this fall. Unfolding History opens on October 6 and runs through November 11, 2006. More than 20 quilts dating from 1750 through 1900 will illustrate the story of quilting’s stylistic evolutions and how those changes reflect womens’ shifting roles.

The exhibition features rarely seen quilts from the Stowe Center’s collection, including portions of a silk quilt made for Stowe’s sister-in-law Eunice, wife of the famed minster Henry Ward Beecher, and a crazy quilt made for the Charles Beecher family Loans from other leading institutions, inducing a Revolutionary-era calamanco from the Henry WHitfield House in Guilford, will round out the exhibition. See the sidebar for more information.

Dawn C. Adiletta is curator of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center and serves on HRJ’s editorial board.

Explore!

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

77 Forest Street, Hartford.

(860) 522-9258; www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org.

The exhibition catalogue, Unfolding History: Quilts from New England Collections (Harriet Beecher Stowe Center: Hartford, CT, 2006), is available at the museum shop.

Crewel World

Hartford is a hotbed of textiles this fall as the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art displays more than a dozen colorful works of needle art from its permanent collection in Crewel World, on view September 23, 2006 to February 25, 2007. Crewel World focuses on works from the late 17th to the mid-18th centuries, when crewel work was a popular choice for home decorations and fashionable accessories. The exhibition, which features bed furnishings, a chasuble, and a schoolgirl’s fanciful sampler, illustrates the changing aesthetic, patterns, and techniques of the period. Crewel World is the last exhibition to be organized under the late Carol Dean Krute, who served as the Atheneum’s curator of costume and textiles for 15 years.

The Wadsworth Atheneum

600 Main Street, Hartford

(860) 278-2760; www.wasdworthatheneum.org.

Footnotes

- Sally Garoute. “Early Colonial Quilts in a Bedding Context.” In Uncoverings, Vol. 1, 1980

- George Francis Dow, The Arts and Crafts of New England, 1704-1775 (Topsfield, MA: The Wayside Press, 1927), 273. Cited from Lynne Z. Bassett and Jack Larkin, Northern Comfort, New England’s Early Quilts 1780-1850 (Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1998), 13.

- Lynne Z. Basset has published numerous works describing New England whole-cloth quilts. Her most recent work appeared in The Magazine Antiques, September 2005, Vol. CLXVIII, No. 3, 120-127.

- Elizabeth Foote, 1775, Colchester, Connecticut, Connecticut Historical Society.

- Ibid.

- Diary of Candace Roberts. 1801-1806, Public Library of Bristol, Connecticut. Donn Haven Lathrop, The National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, Inc. Bulletin. December 2001.

- Jessica Nicoll, “Signature Quilts and the Quaker Community, 1840 – 1860,” in Uncoverings Vol. 7, 1987, 27-37.

- “Accomplishments” were skills expected of both ladies and gentlemen and included romance languages, art, music, and, for some students, dance. Young women often received additional training in fancy sewing.

- Theodore Sizer, et al., “To Ornament Their Minds”: Sarah PIerce’s Litchfield Female Academy 1792 – 1833. (Litchfield, Connecticut: Litchfield Historical Society, 1993), 61

- Ibid., 28.

- Juliet A. L. Tappan (Mrs.) No 3159 Wabash Ave, Chicago, Illinois, to Harriet Beecher Stowe, May 8, 1880.

- Virginia Gunn, “Quilts for Union Soldiers in the Civil War,” in Uncoverings Vol. 6 1985 104-106.

- George Milne, Three Centuries in a Connecticut Hilltop Town: Lebanon, CT (New Canaan, NH: Phoenix Publishing, 1986), 121-131.

- Doreen Bulger Burke, et. al., In Pursuit of Beauty. America and the Aesthetic Movement. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986); Dawn C. Adiletta, “A Matter of Taste: The Aesthetic Movement and Connecticut Crazy Quilts” in Lynne Z. Bassett, ed., What’s New England about New England Quilts? (Sturbridge, MA: Old Sturbridge Village, 1998), 92-103.

- Mrs. John O’Connor, quoted in Eileen Borris, “Crossing Boundaries: The Gendered Meaning of the Arts and Crafts,” The Ideal Home, 1900 – 1920 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993), 34.

- Adiletta, “A Matter of Taste,” 96-100.

- 2003 Quilting in America ™ survey.