By Jason Scappaticci

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc ., Summer 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The 1964−1965 New York World’s Fair attracted approximately 50 million visitors during its two April-to-October seasons, including many from Connecticut. Visitors could see Michelangelo’s Pieta, on display outside of the Vatican for the only time in its history, and Ford’s new muscle car, the Mustang. Situated on more than 640 acres of Flushing Meadows parkland, the fair exuded the spirit of mid-20th-century America, with futuristic, space-themed exhibits and an overarching “Peace Through Understanding” theme. World’s Fair Executive Committee Chair Thomas Deegan predicted in The New York Times it would be “the greatest single event in history.” That prediction was of course a huge exaggeration and the fair was not without its critics and controversy. It was not sanctioned by the Bureau of International Expositions, for instance, because it came too close on the heels of the sanctioned 1962 Seattle World’s Fair; this caused many large countries to decline to participate. And the New York fair attracted civil-rights protests. The New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable summed up the fair’s architecture as a “fascinating free-for all and good clean fun, but it’s rarely good.” (April 22, 1964) Attendance fell far short of the projected 70 million. But, 50 years after it ended, the fair remains one of the defining moments of its era.

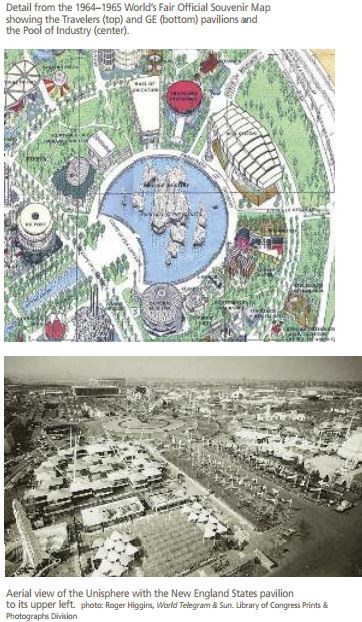

Connecticut’s culture and history were featured in the New England States pavilion, the development of which Connecticut’s governor played a leadership role. State newspapers were peppered with stories as the state planned for the event. “New England Claims World’s Fair Corner,” The Hartford Courant reported on September 23, 1963, the day ground was broken for the New England States pavilion. The pavilion was located next to the Unisphere, a 12-story-high stainless-steel globe that dominated—as it does today—Flushing Meadows Park. Connecticut Governor John Dempsey, chairman of the New England Governors Conference, led the $4 million project. Costs for the pavilion were shared among the six New England states; the Connecticut General Assembly unanimously approved funding the state’s $550,000 share of the cost. At the groundbreaking, Dempsey was the “anchor man among the speakers,” The Courant reported. “We will be here to tell the story of New England today,” Dempsey said, “… and New England tomorrow and to invite the millions who will visit us here to share their future with us.”

The pavilion consisted of hexagonal buildings arranged around a central “village green,” as the Official New York World’s Fair Guide described it. Visitors could tour exhibits highlighting the culture of the New England states, and see New England-made products in the Court of Industry and Commerce. They could browse through the Country Store, which featured New England products and souvenirs, and sample regional dishes such as clam chowder, blueberry slump, and apple grunt at the restaurant.

Connecticut began planning its attractions in 1963 with the formation of a Governor’s Advisory Committee on the World’s Fair. Connecticut was awarded 30 exclusive days to present performances on the village green during the 1964 season alone. Scheduled to perform that year were the Torrington American Legion Fife and Drum Corps, the Windham High School Band, and the Milford Youth Band. West Hartford contributed a dramatization of Noah Webster’s contributions to education and the English language, and Tolland staged a celebration of its 250th anniversary.

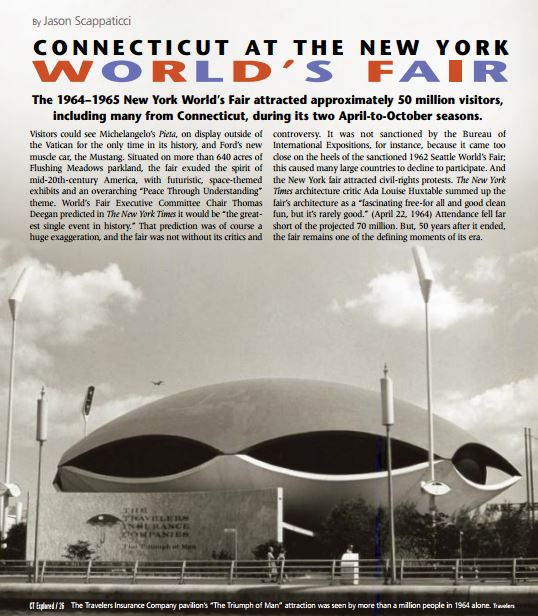

Among the attractions surrounding the fair’s “Pool of Industry” were structures representing two prominent Connecticut corporations. One of the most eye-catching pavilions had a giant bright red roof. Criticized for looking like a giant clam, it was in fact built in the shape of Travelers Insurance Company’s trademark red umbrella. Travelers advertised in the fair’s guidebook that this “uniquely exciting experience” should not be missed. Besides learning about the products Travelers had to offer, visitors could follow “The Triumph of Man,” a 21-minute tour that featured 13 dioramas exploring one and a half million years of human history. Bright red 45-RPM recordings of the tour could be purchased as souvenirs.

General Electric’s pavilion stood across the Pool of Industry from the Travelers. Fairfield-based GE hired Walt Disney and his team of “imagineers” to design one of the most popular attractions of the fair: “Progressland.” Offered in an innovative theater in which the seats circulated around four distinct stage sets, each depicted a different era in American history but all featured the same Audio-Animatronic family. Audience members remained in their seats as they first visited the family in its 1890s home, then progressed to the 1920s and 1940s and finally to 1964. With each time shift, the family’s life had been improved by the addition of new GE products such as a dishwasher, refrigerator, and electric stove. Progressland proved so popular it was later moved to Disneyland in California, opening in 1967, according to yesterland.com/progress.html where it became the General Electric Parade of Progress. It had a later incarnation at Disney World in Florida.

There were other Connecticut connections. The Port of New York Authority announced in a press release on October 10, 1963 that its “Port Authority Heliport…the aerial gateway to the Fair … …will be operated by the United Aircraft International Corporation of East Hartford, Connecticut…[with]sightseeing flights conducted with United Aircraft’s Sikorsky Division’s twin-turbine S-61 helicopters.” New Canaan resident and member of the “Harvard Five” architect Philip Johnson designed the New York State pavilion—part of which still stands and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places—out of his New York office. Fellow New Canaan resident and Harvard Five architect Eliot Noyes was the consultant director of design for the Westinghouse Time Capsule. Noyes’s initial design for a Westinghouse pavilion consisting of eight huge spheres, each 45 feet across, enclosing exhibition spaces was unrealized and Westinghouse scaled back to the time capsule project.

Connecticut took home at least one piece of the fair. When the festivities ended, portions of the Vatican pavilion were purchased and incorporated into the design of Saint Mary Mother of the Redeemer Church in Groton by architect William F. Herman Jr. of Mystic, according to the church’s Web site. The groundbreaking took place in December 1966. The pavilion’s golden-anodized aluminum cross, stained-glass windows, walnut reredos, and testor were all incorporated into the church.

Connecticut took home at least one piece of the fair. When the festivities ended, portions of the Vatican pavilion were purchased and incorporated into the design of Saint Mary Mother of the Redeemer Church in Groton by architect William F. Herman Jr. of Mystic, according to the church’s Web site. The groundbreaking took place in December 1966. The pavilion’s golden-anodized aluminum cross, stained-glass windows, walnut reredos, and testor were all incorporated into the church.

Jason Scappaticci is director of student success and first year programs at Manchester Community College.

Read more stories from the Summer 2015 issue