(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

Christopher Wigren’s forthcoming book Connecticut Architecture: Stories of 100 Places (Wesleyan University Press, expected Fall 2018) is an introduction to Connecticut’s built environment through stories about 100 places. Selections adapted here, with the permission of Wesleyan University Press, highlight some of the ways the people of Connecticut have preserved and reused historic resources.

Resistance to Modernism fed the rise of historic preservation in the 20th century. Preservation had roots in the late 19th-century rediscovery of American history and architecture. Early preservationists had concentrated on maintaining sites of historic importance as museums and restoring colonial houses as private homes. But reaction to the widespread demolition of urban renewal and the unfamiliar forms of Modernist architecture brought preservation to public consciousness, and a broader movement emerged.

Resistance to Modernism fed the rise of historic preservation in the 20th century. Preservation had roots in the late 19th-century rediscovery of American history and architecture. Early preservationists had concentrated on maintaining sites of historic importance as museums and restoring colonial houses as private homes. But reaction to the widespread demolition of urban renewal and the unfamiliar forms of Modernist architecture brought preservation to public consciousness, and a broader movement emerged.

In spite of its active Modernists, Connecticut, with its long history, actively took to preservation. As early as 1955 the state established the Connecticut Historical Commission to promote its historic heritage.

Two developments in 1959 indicated the growing influence and changing face of the preservation movement. First, the town of Litchfield established a local historic district, which required that a town commission approve any alterations to the exterior of buildings or any new construction within the district. Established under special enabling legislation from the Connecticut General Assembly, Litchfield’s was the first of what now are more than 100 such districts across the state.

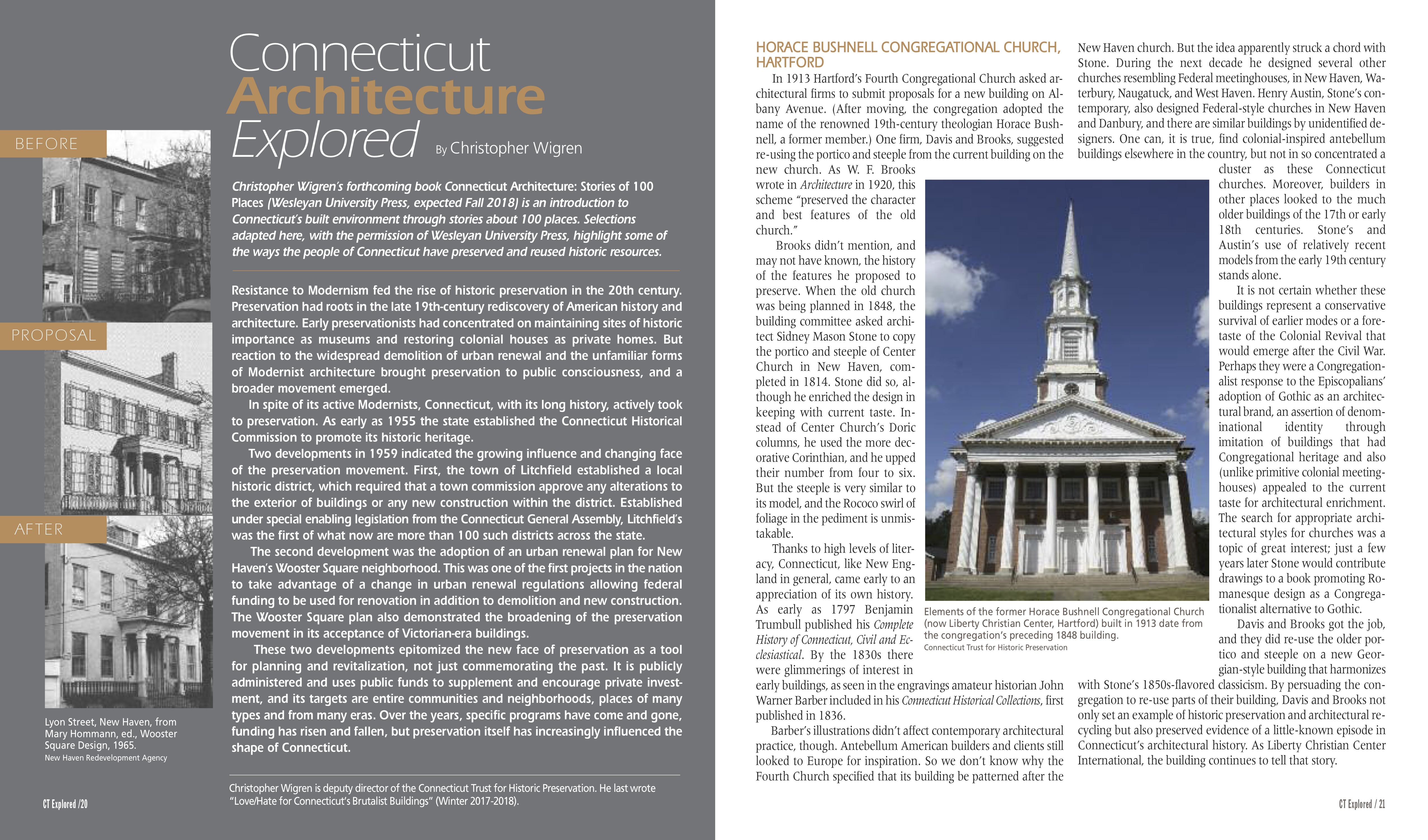

The second development was the adoption of an urban renewal plan for New Haven’s Wooster Square neighborhood. This was one of the first projects in the nation to take advantage of a change in urban renewal regulations allowing federal funding to be used for renovation in addition to demolition and new construction. The Wooster Square plan also demonstrated the broadening of the preservation movement in its acceptance of Victorian-era buildings.

These two developments epitomized the new face of preservation as a tool for planning and revitalization, not just commemorating the past. It is publicly administered and uses public funds to supplement and encourage private investment, and its targets are entire communities and neighborhoods, places of many types and from many eras. Over the years, specific programs have come and gone, funding has risen and fallen, but preservation itself has increasingly influenced the shape of Connecticut.

Horace Bushnell Congregational Church, Hartford

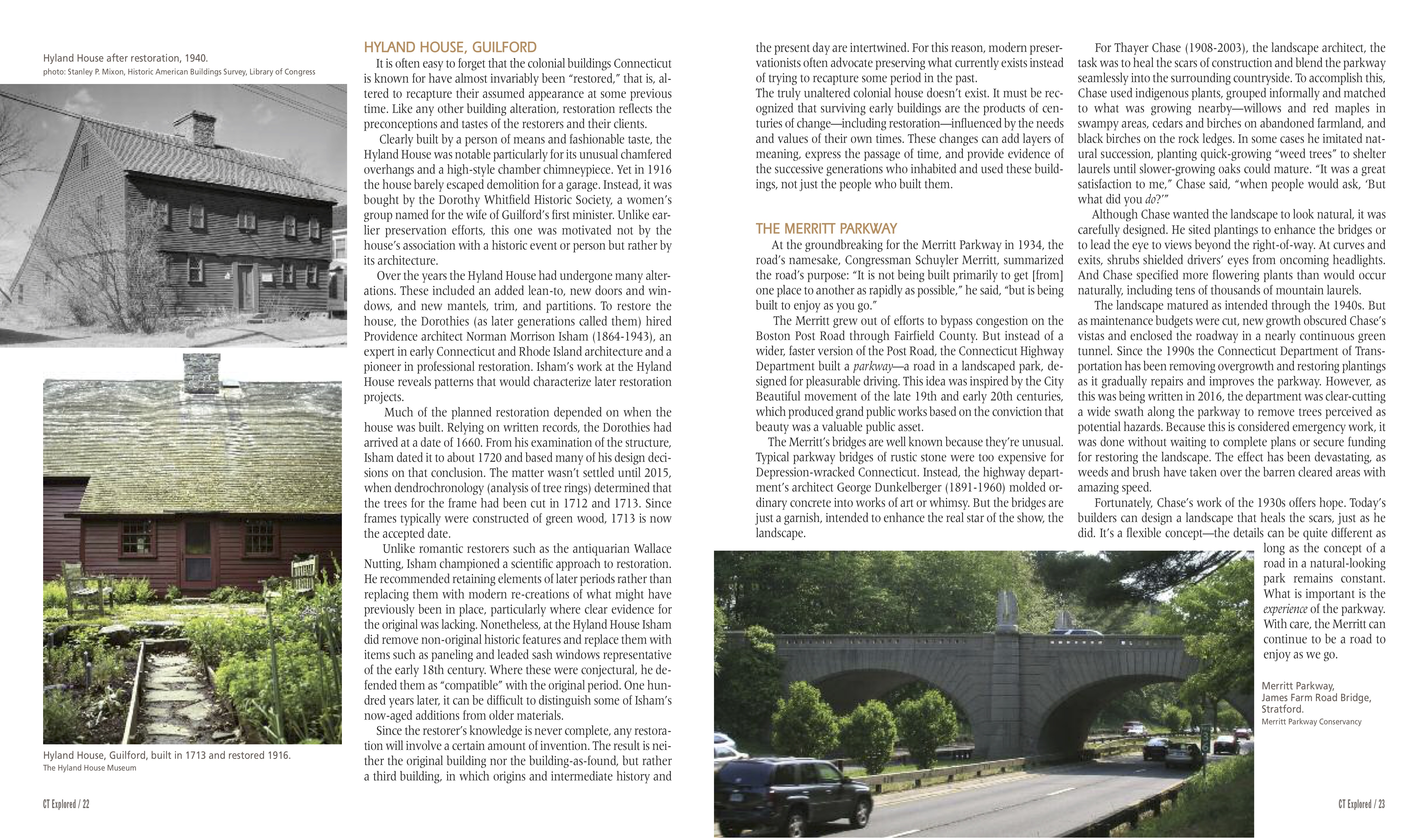

In 1913 Hartford’s Fourth Congregational Church asked architectural firms to submit proposals for a new building on Albany Avenue. (After moving, the congregation adopted the name of the renowned 19th-century theologian Horace Bushnell, a former member.) One firm, Davis and Brooks, suggested re-using the portico and steeple from the current building on the new church. As W. F. Brooks wrote in Architecturein 1920, this scheme “preserved the character and best features of the old church.”

Brooks didn’t mention, and may not have known, the history of the features he proposed to preserve. When the old church was being planned in 1848, the building committee asked architect Sidney Mason Stone to copy the portico and steeple of Center Church in New Haven, completed in 1814. Stone did so, although he enriched the design in keeping with current taste. Instead of Center Church’s Doric columns, he used the more decorative Corinthian, and he upped their number from four to six. But the steeple is very similar to its model, and the Rococo swirl of foliage in the pediment is unmistakable.

Thanks to high levels of literacy, Connecticut, like New England in general, came early to an appreciation of its own history. As early as 1797 Benjamin Trumbull published his Complete History of Connecticut, Civil and Ecclesiastical. By the 1830s there were glimmerings of interest in early buildings, as seen in the engravings amateur historian John Warner Barber included in his Connecticut Historical Collections, first published in 1836.

Barber’s illustrations didn’t affect contemporary architectural practice, though. Antebellum American builders and clients still looked to Europe for inspiration. So we don’t know why the Fourth Church specified that its building be patterned after the New Haven church. But the idea apparently struck a chord with Stone. During the next decade he designed several other churches resembling Federal meetinghouses, in New Haven, Waterbury, Naugatuck, and West Haven. Henry Austin, Stone’s contemporary, also designed Federal-style churches in New Haven and Danbury, and there are similar buildings by unidentified designers. One can, it is true, find colonial-inspired antebellum buildings elsewhere in the country, but not in so concentrated a cluster as these Connecticut churches. Moreover, builders in other places looked to the much older buildings of the 17th or early 18th centuries. Stone’s and Austin’s use of relatively recent models from the early 19th century stands alone.

It is not certain whether these buildings represent a conservative survival of earlier modes or a foretaste of the Colonial Revival that would emerge after the Civil War. Perhaps they were a Congregationalist response to the Episcopalians’ adoption of Gothic as an architectural brand, an assertion of denominational identity through imitation of buildings that had Congregational heritage and also (unlike primitive colonial meetinghouses) appealed to the current taste for architectural enrichment. The search for appropriate architectural styles for churches was a topic of great interest; just a few years later Stone would contribute drawings to a book promoting Romanesque design as a Congregationalist alternative to Gothic.

Davis and Brooks got the job, and they did re-use the older portico and steeple on a new Georgian-style building that harmonizes with Stone’s 1850s-flavored classicism. By persuading the congregation to re-use parts of their building, Davis and Brooks not only set an example of historic preservation and architectural recycling but also preserved evidence of a little-known episode in Connecticut’s architectural history. As Liberty Christian Center International, the building continues to tell that story.

It is often easy to forget that the colonial buildings Connecticut is known for have almost invariably been “restored,” that is, altered to recapture their assumed appearance at some previous time. Like any other building alteration, restoration reflects the preconceptions and tastes of the restorers and their clients.

Clearly built by a person of means and fashionable taste, the Hyland House was notable particularly for its unusual chamfered overhangs and a high-style chamber chimneypiece. Yet in 1916 the house barely escaped demolition for a garage. Instead, it was bought by the Dorothy Whitfield Historic Society, a women’s group named for the wife of Guilford’s first minister. Unlike earlier preservation efforts, this one was motivated not by the house’s association with a historic event or person but rather by its architecture.

Over the years the Hyland House had undergone many alterations. These included an added lean-to, new doors and windows, and new mantels, trim, and partitions. To restore the house, the Dorothies (as later generations called them) hired Providence architect Norman Morrison Isham (1864-1943), an expert in early Connecticut and Rhode Island architecture and a pioneer in professional restoration. Isham’s work at the Hyland House reveals patterns that would characterize later restoration projects.

Much of the planned restoration depended on when the house was built. Relying on written records, the Dorothies had arrived at a date of 1660. From his examination of the structure, Isham dated it to about 1720 and based many of his design decisions on that conclusion. The matter wasn’t settled until 2015, when dendrochronology (analysis of tree rings) determined that the trees for the frame had been cut in 1712 and 1713. Since frames typically were constructed of green wood, 1713 is now the accepted date.

Unlike romantic restorers such as the antiquarian Wallace Nutting, Isham championed a scientific approach to restoration. He recommended retaining elements of later periods rather than replacing them with modern re-creations of what might have previously been in place, particularly where clear evidence for the original was lacking. Nonetheless, at the Hyland House Isham did remove non-original historic features and replacethem with items such as paneling and leaded sash windows representative of the early 18th century. Where these were conjectural, he defended them as “compatible” with the original period. One hundred years later, it can be difficult to distinguish some of Isham’s now-aged additions from older materials.

Since the restorer’s knowledge is never complete, any restoration will involve a certain amount of invention. The result is neither the original building nor the building-as-found, but rather a third building, in which origins and intermediate history and the present day are intertwined. For this reason, modern preservationists often advocate preserving what currently exists instead of trying to recapture some period in the past.

The truly unaltered colonial house doesn’t exist. It must be recognized that surviving early buildings are the products of centuries of change—including restoration—influenced by the needs and values of their own times. These changes can add layers of meaning, express the passage of time, and provide evidence of the successive generations who inhabited and used these buildings, not just the people who built them.

The Merritt Parkway

At the groundbreaking for the Merritt Parkway in 1934, the road’s namesake, Congressman Schuyler Merritt, summarized the road’s purpose: “It is not being built primarily to get [from]one place to another as rapidly as possible,” he said, “but is being built to enjoy as you go.”

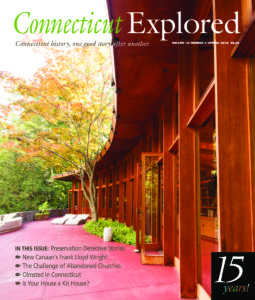

The Merritt grew out of efforts to bypass congestion on the Boston Post Road through Fairfield County. But instead of a wider, faster version of the Post Road, the Connecticut Highway Department built a parkway—a road in a landscaped park, designed for pleasurable driving. This idea was inspired by the City Beautiful movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which produced grand public works based on the conviction that beauty was a valuable public asset.

The Merritt’s bridges are well known because they’re unusual. Typical parkway bridges of rustic stone were too expensive for Depression-wracked Connecticut. Instead, the highway department’s architect George Dunkelberger (1891-1960) molded ordinary concrete into works of art or whimsy. But the bridges are just a garnish, intended to enhance the real star of the show, the landscape.

For Thayer Chase (1908-2003), the landscape architect, the task was to heal the scars of construction and blend the parkway seamlessly into the surrounding countryside. To accomplish this, Chase used indigenous plants, grouped informally and matched to what was growing nearby—willows and red maples in swampy areas, cedars and birches on abandoned farmland, and black birches on the rock ledges. In some cases he imitated natural succession, planting quick-growing “weed trees” to shelter laurels until slower-growing oaks could mature. “It was a great satisfaction to me,” Chase said, “when people would ask, ‘But what did you do?’”

Although Chase wanted the landscape to look natural, it was carefully designed. He sited plantings to enhance the bridges or to lead the eye to views beyond the right-of-way. At curves and exits, shrubs shielded drivers’ eyes from oncoming headlights. And Chase specified more flowering plants than would occur naturally, including tens of thousands of mountain laurels.

The landscape matured as intended through the 1940s. But as maintenance budgets were cut, new growth obscured Chase’s vistas and enclosed the roadway in a nearly continuous green tunnel. Since the 1990s the Connecticut Department of Transportation has been removing overgrowth and restoring plantings as it gradually repairs and improves the parkway. However, as this was being written in 2016, the department was clear-cutting a wide swath along the parkway to remove trees perceived as potential hazards. Because this is considered emergency work, it was done without waiting to complete plans or secure funding for restoring the landscape. The effect has been devastating, as weeds and brush have taken over the barren cleared areas with amazing speed.

Fortunately, Chase’s work of the 1930s offers hope. Today’s builders can design a landscape that heals the scars, just as he did. It’s a flexible concept—the details can be quite different as long as the concept of a road in a natural-looking park remains constant. What is important is the experienceof the parkway. With care, the Merritt can continue to be a road to enjoy as we go.

Read More About the Merritt Parkway: “Preserving the Merritt Parkway,” Spring 2008

Cheney Yarn Dye House, Manchester

For almost as long as people have erected buildings, they’ve adapted them to new purposes. Reuse usually was a matter of frugality. But sometimes the motivation was the desire to retain the building for its historical or architectural significance—in short, historic preservation. In the 20th century, preservationists gave this age-old practice a formal name: “adaptive use.”

One of Connecticut’s most extensive adaptive-use efforts has been the gradual conversion to new purposes of the former Cheney Brothers silk mills in Manchester. At its peak in the 1920s, Cheney Brothers was the nation’s biggest silk producer, occupying approximately 1.3 million square feet of space in eight principal buildings. After World War II, however, business faltered; in 1954 the family sold the company, and the mills soon closed. Beginning in the 1970s, the Town of Manchester initiated redevelopment of the vacant mills. The most recent to be completed is the former Yarn Dye House, converted to apartments in 2009.

Public funding has helped make adaptive use feasible. Since 1976 the federal government has offered tax credits to developers who renovate historic buildings. States, including Connecticut, have instituted similar programs. To qualify, projects must adhere to a set of preservation guidelines called the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation. Commonly known as the Secretary’s Standards, their goal is to retain a building’s original materials and appearance as much as possible.

Renovating a building under the Secretary’s Standards requires balancing preservation requirements against alterations needed to accommodate a new use. For example, converting the Yarn Dye House to apartments required subdividing the open manufacturing spaces. Yet industrial character still comes through in the exposed brick walls, concrete ceilings, and steel-and-concrete structural columns. The original windows were too deteriorated to retain, but the replacements imitate their glazing pattern while modifying their construction to allow the addition of screens. Particularly noteworthy are the 17-foot-tall first-story windows, which provided ventilation to dry the dyed yarn and vent off fumes. To avoid dividing the windows, the first-floor units were designed as double-height spaces with 23-foot ceilings and lofts inside.

Other financing possibilities also influenced the reuse of the Yarn Dye House: in addition to historic rehabilitation tax credits, federal and state affordable-housing funding was available, so the building was developed as subsidized housing for tenants who meet low-income qualifications. Satisfying the requirements of that funding source further complicated the design process. Finally, contamination had to be cleaned up and structural deterioration corrected.

Despite the complexity of the issues to be addressed, reusing the Yarn Dye House was seen as worth the effort by the Town of Manchester, the federal and state governments, and the developer. The building’s historic significance, as part of the larger Cheney complex, accounts for part of this, as does the availability of financing for reuse that couldn’t be tapped for new construction. But the appeal of the building’s industrial character also played an important role. The Yarn Dye House conversion is one of many that show us that buildings can live multiple lives as they continue to be occupied, maintained, and even loved long after their original purpose has disappeared.

Read more about the Cheney Silk story: “The Cheney Company Housing Auction of 1937,” and “Cheney Mills: Life in a Mill Town”

Christopher Wigren is deputy director of the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation. He last wrote “Love/Hate for Connecticut’s Brutalist Buildings” (Winter 2017-2018).

Explore!

Horace Bushnell Congregational Church, now Liberty Christian Center International, 750 Albany Avenue, Hartford. Built 1913 – 1914, Davis and Brooks; steeple and portico date to 1848 – 1850, Sidney Mason Stone.

Hyland House, 84 Boston Street, Guilford. Built c. 1713. Restored 1916 – 1917, Norman M. Isham. hylandhouse.org.

Merritt Parkway, Connecticut Route 15, Greenwich to Stratford. Built 1934 – 1940, Connecticut Highway Department, Warren Creamer and Leslie G. Sumner, engineers; George Dunkelberger, architect; Weld Thayer Chase, landscape architect. Merritt Parkway Conservancy

Cheney Brothers Yarn Dye House(Dye House Apartments), 31 Cooper Hill Street, Manchester. Built 1914. 2009, Crosskey Architects; Simon Konover Company, developer.