By Fred Calabretta and Edward Baker

By Fred Calabretta and Edward Baker

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Five museums and historical societies in southeastern Connecticut collaborated on an exhibition commemorating the bicentennial of the War of 1812. “The Rockets’ Red Glare”: Connecticut and the War of 1812 opened July 6, 2012 at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum in New London and was on view through December.

Historic objects and images drawn from the collections of each of the partners and items from other museums and private collections shed light on this often-overlooked conflict and its considerable impact on the people of New London County and the state. Partnering organizations include the Stonington Historical Society, Mystic Seaport Museum, the New London County Historical Society, the New London Maritime Society, and the Lyman Allyn Art Museum.

The War of 1812 disrupted Connecticut’s important maritime commerce, profoundly affecting the entire state. Consequently, the exhibition included maritime-related material such as ship models, rare documents, paintings, and prints—many with direct associations to the state. In addition, Connecticut’s citizen soldiers—the state’s militia—served in large numbers during the war, especially in defense of the coast. Two rare militia uniform coats, both worn with pride by Connecticut men, were featured along with other militia-related objects.

The exhibition focused on the war’s impact and meaning for all of Connecticut’s citizens. Among the objects conveying this key theme were several early views and maps, a tea set saved by a local woman as the British threatened to come ashore in Stonington, and a plow abandoned by a local farmer as he rushed off to defend the village.

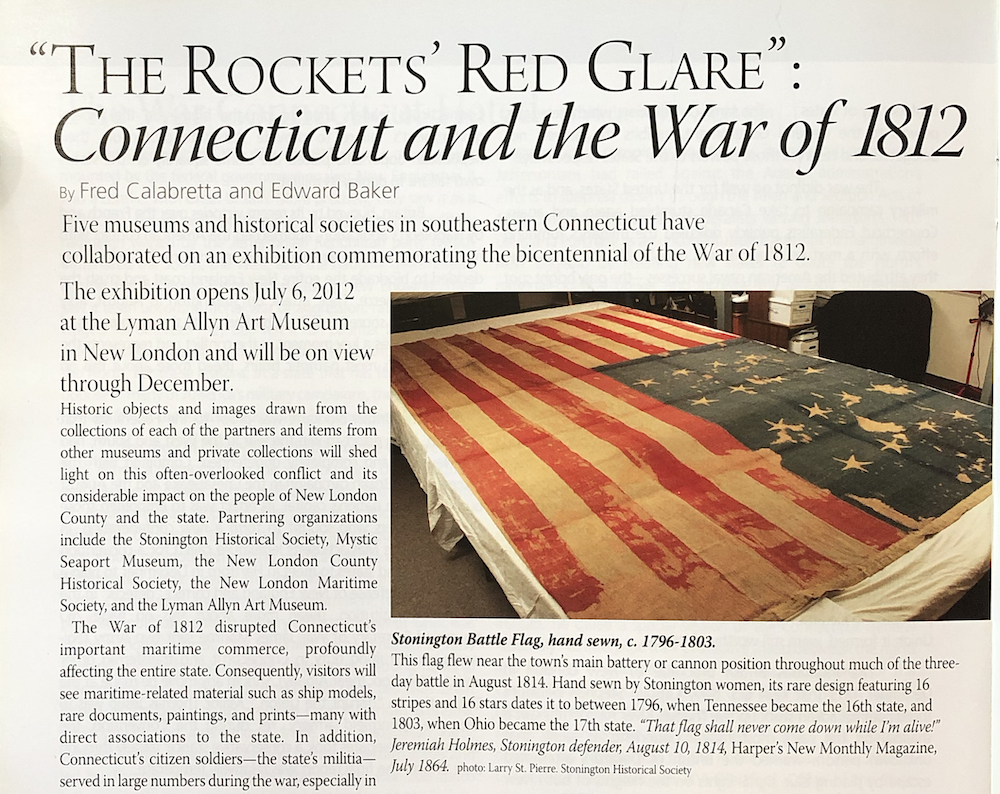

One particular object—Stonington’s battle flag—stands out as the signature piece of the exhibition. (Read more about the flag on page 44.) This 12 foot-by-19-foot American flag flew over the defenders during the British attack on the village in 1814. Prized for two centuries by the people of Stonington, this unique flag may be considered Connecticut’s own Star-Spangled Banner.

The War of 1812 ended without a clear victor, yet Connecticut, along with the other states, experienced its lasting impact. Several groups of objects reflected the war’s legacy. Among these were images and items associated with some of the war’s heroes, especially those with strong Connecticut ties such as naval officers Isaac Hull and Thomas Macdonough and Groton heroine Anna Warner Bailey.

“The Rockets’ Red Glare” exhibition was made possible with generous support from the Connecticut Humanities Council. Additional funding was provided by the Coby Foundation and the Edgard & Geraldine Feder Foundation.

Edward Baker was executive director of the New London County Historical Society. Fred Calabretta is curator of collections at Mystic Seaport Museum.

“The Rockets’ Red Glare”: Connecticut and the War of 1812, a book published by the New London County Historical Society to accompany the exhibition, is available on line at newlondonhistory.org or at the Lyman Allyn Museum of Art and the Mystic Seaport Book Store, $18.

John Miner’s coat, cotton with linen lining, home produced, c. 1814. Letter (below) and coat: Stonington Historical Society

The attack on Stonington placed ordinary citizens in extraordinary roles. More accustomed to farming than military duty, 19-year-old John Miner was wounded while defending the village.

“I am sending you by Parcel Post this day a coat worn by my father the late John Miner whilst engaged in assisting manning a gun in the Battery of Stonington on the 10th day of August 1814.

I have heard my father say due to the haste and excitement of the volunteers they failed to properly cool their gun before pouring into its muzzle the powder, which due to the excessive heat of the gun caused the powder to explode prematurely, as you may see by reference to the coat – burned and torn upon the neck and shoulder.”

John Haley Miner, Bozrah, Connecticut, June 15, 1914

Photo postcard of parade, 1914. Stonington Historical Society

The battle has been celebrated and commemorated throughout the years, especially in 1914 when the centennial celebration lasted for three days and attracted thousands of participants and visitors. The boy holding the flag is the great-grandson of 1814 defender Jeremiah Holmes.

[image, top of post] Stonington Battle Flag, hand sewn, c. 1796-1803. photo: Larry St. Pierre. Stonington Historical Society

This flag flew near the town’s main battery or cannon position throughout much of the three-day battle in August 1814. Hand sewn by Stonington women, its rare design featuring 16 stripes and 16 stars dates it to between 1796, when Tennessee became the 16th state, and 1803, when Ohio became the 17th state. “That flag shall never come down while I’m alive!” Jeremiah Holmes, Stonington defender, August 10, 1814, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, July 1864

Sea bag with embroidery, c. 1840. (c) Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT

During the war and continuing throughout the 19th century, Americans created visual representations of the war’s sea battles, which continued to inspire them long after the actual events. A skilled craftsman carefully embroidered War of 1812 naval scenes on this sailor’s sea bag, which dates to about 1840. The designs reflect the country’s pride in the men and ships of the navy. This sea bag’s history also includes a 2001 appearance on the popular television program “Antiques Roadshow.”

American-made Empire-style dress, fabric manufactured in Great Britain, c. 1810. (c) Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT

The Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812 greatly restricted maritime commerce. Connecticut’s residents found themselves cut off from imported products they needed or desired. This empire-style dress, inspired by Josephine, the wife of Napoleon of France, was sewn from cotton fabric produced and printed in Great Britain. Such fabric became increasingly difficult to obtain after 1807. Connecticut and other New England states responded with increased textile manufacturing, an important result of the War of 1812.

[partial image, above left]“New London Encampment of War of 1812,” painting on glass, unidentified artist, 1815. Lyman Allyn Art Museum

The United States maintained a relatively small standing—or permanent—army in the years following the Revolutionary War, relying instead on the militia—state and local military organizations consisting of citizen soldiers. Residents of every town, totaling more than 10,000 men, served in Connecticut’s militia from 1812 to 1815. Many stood guard or manned forts at Bridgeport, New Haven, Killingworth, Saybrook, Waterford, New London, Groton, Mystic, and Stonington. This scene depicting men relaxing, lounging, and smoking in their tidy uniforms suggests a summer outing rather than a military encampment. In actuality, Connecticut militiamen and U.S. Army troops commonly endured miserable food, leaky tents, and poor equipment.

“The American Privateer ‘General Armstrong’ Capt. Sam. Reid,” hand-colored lithograph by N. Currier, c. 1830. (c) Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT

American seamen and their officers, including those from New England, possessed deep-rooted maritime traditions, skills, and experience that helped propel American naval and armed merchant ships to considerable success during the War of 1812.

Throughout the war hundreds of American vessels known as privateers supported their country’s war effort by disrupting British shipping. These merchant ships carried U.S. government licenses authorizing them to attack British naval or merchant vessels. American law entitled privateer captains and crews to half of the value of any captured ship and its cargo. Fame was another reward for some successful privateers, such as the General Armstrong and her Connecticut-born captain Samuel Reid about whom this ballad was written a century later.

The name of Reid and the Fame of Reid

And the flag of his ship and crew

Are brighter far than sea or star

Or the heavens’ red, white, and blue:

So lift your voices once again

For the land we love so dear,

For the fighting Captain and the men

Of the Yankee Privateer

– “The Armstrong at Fayal,” Wallace Rice, 1903

Tea set (sugar bowl and creamer) hidden by Olive Spicer of Stonington to protect it from the British, 1814. Stonington Historical Society

Consternation flew through the town. The sick and the aged were removed with haste. The women and children with loud cries were seen running in every direction. Some of the most valuable articles were hastily got off by hand, and others placed in the gardens and lots or thrown into wells, to save them from impending conflagration. Connecticut Courant, August 23, 1814

“Battle of Lake Champlain—M’Donough’s Victory, 1814,” attributed to Nathaniel S. Finney, scrimshaw whale’s tooth, c. 1848. (c) Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT

The war created a number of celebrated American naval heroes, including several with strong ties to Connecticut. Thomas Macdonough of Middletown earned fame for leading his squadron’s major victory on Lake Champlain.

The war created a number of celebrated American naval heroes, including several with strong ties to Connecticut. Thomas Macdonough of Middletown earned fame for leading his squadron’s major victory on Lake Champlain.

Oh, our main decks were grim and our gun decks were gory,

And many a brave brow was pallid with pain;

And while some won death, yet we all won glory,

Who fought with MACDONOUGH that day on Champlain

– “The Battle of Plattsburgh Bay,” Clinton Scollard, 1903

Read more!

Return to Spring 2012