(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

What makes a person or a family famous? We all know about the families with names on buildings and boulevards. No doubt they have a right to this fame and much of it is well-earned. But there is a hidden and more muted history of families whose impact, while not as well known, is profound and understated yet expressed generation after generation; families whose instincts lead them to right wrongs. I was lucky enough to be introduced to such a family right here in Connecticut, and it has been my passion to bring their story to the world.

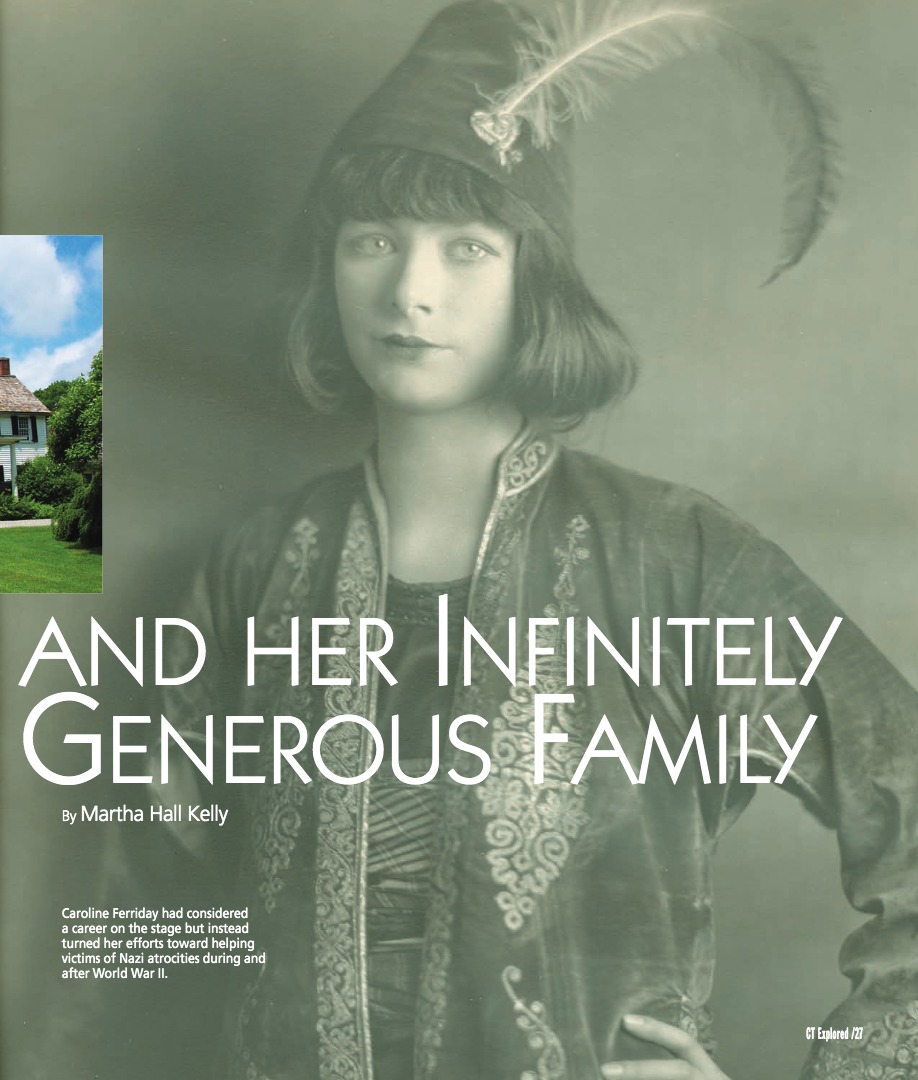

I stumbled upon this family one grey Mother’s Day in 2003, shortly after my mother had died. For many years I had carried in my wallet an article from Victoria magazine (May 1999) about a lovely old house and museum in Bethlehem, Connecticut, but, being a full-time mother of three, I had never had time to visit. The article, Caroline’s Incredible Lilacs, showed Caroline Ferriday’s stately, Federal-style house, known today as The Bellamy Ferriday House and Garden, the beloved summer home of the Ferriday family of New York City, which Caroline Ferriday donated to Connecticut Landmarks after her death in 1993. The article also pictured her glorious lilac bushes in bloom and a photo of her as a lovely, 20-something Broadway actress. I lived in Fairfield at the time, and my husband suggested he take care of our children while I drive up to visit this historic home and gardens. That day my life changed forever.

The house did not disappoint. The gardens were exquisite, with the lilacs in full bloom, in colors from pale pink to deep aubergine. I learned Caroline and her mother Eliza had traveled extensively and brought back specimen plants from around the world, including many antique roses, Caroline’s favorites.

On a whim I decided to tour the interior of the house with the docent and learned that the house had been built by Reverend Joseph Bellamy, an American Congregationalist pastor, educator, and theologian in New England in the second half of the 18th century. Bellamy founded and named Bethlehem and hosted many theology students at his home.

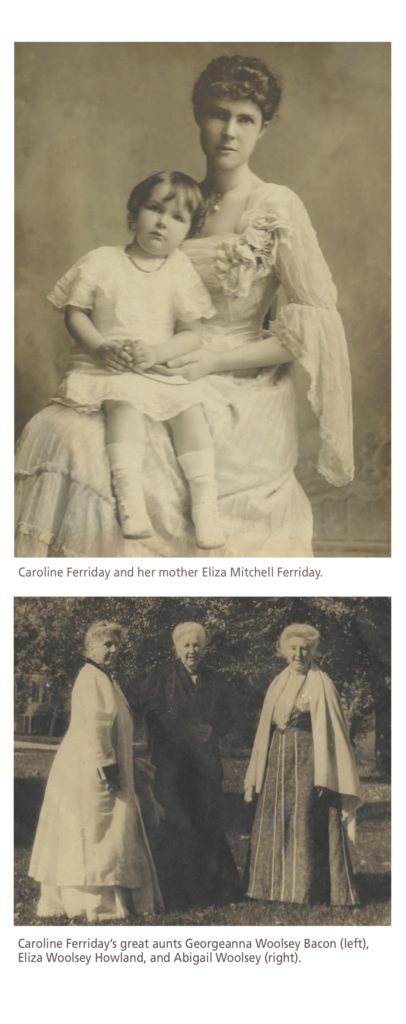

I loved touring the lovely white clapboard house, which was filled with Caroline’s original furnishings and books, and enjoyed the docent’s stories about Caroline’s philanthropic ancestors, her mother Eliza Mitchell Ferriday, grandmother Caroline Woolsey Mitchell, and most of all her great-grandmother Jane Eliza Woolsey, a staunch abolitionist with Mayflower lineage.

At the end of the tour, on the landing outside Caroline’s bedroom, the docent led me to Caroline’s desk, kept just as she’d left it. Caroline was a tremendous Francophile, a love of France instilled in her by her father, and her hulking Remington typewriter sat near framed portraits hung on the wall of Charles DeGaulle and Napoleon Bonaparte.

“Caroline used that typewriter so much,” the docent said. “She raised money for orphaned children of French resistance fighters during World War II.”

“Caroline used that typewriter so much,” the docent said. “She raised money for orphaned children of French resistance fighters during World War II.”

I noticed a black-and-white photograph on the desk, of 50 or so smiling, middle-aged women lined up three rows deep. “Those are The Rabbits,” the docent said. “Polish Catholic girls arrested for participating in the Polish underground once Hitler occupied Poland. They were sent to Ravensbrück, Hitler’s only major, all-female concentration camp, and 74 of them were chosen personally by Heinrich Himmler to become the subjects of despicable medical experiments. Doctors at the camp surgically implanted dirt and glass and tetanus cultures into the young women’s legs to promote infections and test the efficacy of infection-fighting sulfa drugs. Those who survived the experiments, some operated on multiple times, became known at the camp as The Rabbits, since they hopped about on their injured legs and because they were the Nazis’ laboratory animals. Just girls at the time they were experimented on, the youngest was 14 years old.”

The guide went on to explain that when the surviving “Rabbits” returned to Poland after Ravensbrück was liberated in April 1945, many of them suffered behind the Iron Curtain with little medical care. Soon, Caroline Ferriday heard about them from her friend Genevieve DeGaulle, General Charles DeGaulle’s niece, who had been imprisoned at the camp with the Polish women and had forged lifelong friendships with them. Ferriday went on to fight the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to bring the women across the Iron Curtain of Communist Poland and then rallied America behind those that survived and brought them to the United States for rehabilitation—and the trip of a lifetime. (See “Caroline Ferriday: A Godmother to Ravensbrück Survivors,” Winter 2011/2012.)

Clearly there was a lot more to Caroline Ferriday than beautiful gardens, and the story haunted me all the way home to Fairfield. Why did no one know about this phenomenal woman and what she had done? How could such an important story just get lost?

After that trip I drove up to Bethlehem every chance I got to sit in the cool root cellar where Ferriday’s archives are kept, paging through the letters and gardening books she left, as if absorbing her. What legacy had she inherited from her ancestors that made her this staunchly principled, strong woman?

Ferriday, it turns out, is a descendant of some of the most remarkable women in American history, the so-called Woolsey women. In the archives I found she had meticulously documented her family history, with notes and countless photos of them. She kept everything, even the little things—like dry-cleaning tickets, horse-show flyers, notes written on envelope backs. I developed a rich sense of her personality and passions.

Ferriday had been raised in New York City, attended the Chapin School in Manhattan, and had led a privileged upbringing typical of the times for the wealthiest New Yorkers. She developed an early interest in the theater, writing and acting in school plays, and then landed a role in a Broadway production of The Merchant of Venice that starred her mother Eliza’s dear friend and Caroline’s acting mentor, Julia Marlowe, the celebrated Shakespearean stage actress. Marlowe and her husband E.H. Sothern were one of the most famous theater couples of the day and a tremendous help to Ferriday in her career.

But the stage was not to be Caroline’s enduring legacy. In the late 1930s, as war was starting to savage Europe, she volunteered at the French consulate in New York City and started raising money to benefit French children orphaned in the war. Soon after the war, she established the American branch of the National Association of Deportees and Internees of the Resistance (ADIR). Founded in 1945 by female members of the French resistance who had survived their internment in the German camps, the ADIR raised money to help women of all nationalities get back on their feet after returning from the camps. Ferriday also worked to get reparations from the German government for the “Rabbits,” and, assisted by Norman Cousins, editor of The Saturday Review, she campaigned to bring the “Rabbits” (or “Lapins,” as she sometimes called them) to America for much-needed medical attention. She eventually was successful in winning reparations for the women. I soon realized that Ferriday had grown to think of the Polish women as part of her family. They called her “Godmother,” and from her letters it was clear she treated them like daughters.

To bring Ferriday’s story alive I had to dig deep into the “Rabbits’” story, to see where they grew up and to experience their odyssey. My son and I traveled to Lublin, Poland to see where they had lived and joined the underground resistance, and then on to Germany, 56 miles north of Berlin to the city of Furstenberg, the site of the Ravensbrück concentration camp, now a national memorial.

During World War II, the Nazis wanted the outside world to see Ravensbrück, with its window boxes on the barracks planted with flowers and beautiful linden trees lining the street on which the barracks stood, as a showplace for the German Red Cross. A cage of exotic parrots and monkeys greeted visitors when they approached the commandant’s office. But it was actually a place of unimaginable cruelty, where thousands of women and children died of starvation, disease, and in the makeshift gas chamber. A place built for 3,000 women that by the end of the war held 50,000. Stepping off onto the same train platform the “Rabbits” had walked on more than 70 years before, I could only imagine their terror and despair.

The barracks are long gone now, taken for firewood by the people of Furstenberg, who were near famine at the war’s end, or taken down by the Soviet troops billeted there once they liberated the camp: no one knows for sure. But you can still see the prison bunker, the shooting wall the women were all so terrified of, the crematorium, the lake where the camp staff tossed the ashes of the mothers and sisters and daughters. You can walk up steep stairs to a ridge on which stands Commandant Suhren’s house, a snug alpine cottage that still boasts Nazi-red kitchen cabinets.

After that trip, I dug in to every source I could find, including Ferriday’s archives in Paris and at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. I spoke to those who knew her. What emerged was a true story of tremendous suffering and incredible hope, and it fueled my desire to write her story.

Once Lilac Girls was published I received a tremendous amount of mail about Ferriday and her philanthropy. Readers loved her independent streak and way of advocating for a cause, and I dug into the archives to see where that came from. It soon became clear it all came from her mother, Eliza Mitchell Ferriday.

Like Caroline the only child of wealthy parents, Eliza was raised in a privileged but strict household. Her father Edward Mitchell was a lawyer for the Republican Party in New York and had met Eliza’s mother Carry (Caroline Ferriday’s grandmother) during the Civil War through her sisters. He volunteered onboard The Daniel Webster, one of the hospital ships Georgeanne and Eliza Woolsey worked on. After their marriage, Eliza’s parents lived in a New York City apartment on 51st Street and enjoyed their seaside home, The Mitchell Cottage on Gin Lane in Southampton, Long Island—less cottage and more estate.

In 1900 Eliza married Henry McKean Ferriday, a prosperous dry goods merchant, descended from a wealthy lumber family from Ferriday, Louisiana. The couple summered at The Mitchell Cottage until their daughter Caroline was born. The salt air did not agree with her, and they looked to Connecticut for a country home. According to an early memoir, Caroline wrote that her father was the one who wanted to buy what is today The Bellamy-Ferriday House. The home’s dilapidated state did not impress her mother nor her grandmother, but the Ferridays eventually decided to buy the old place, which they named “The Hay.”

In 1900 Eliza married Henry McKean Ferriday, a prosperous dry goods merchant, descended from a wealthy lumber family from Ferriday, Louisiana. The couple summered at The Mitchell Cottage until their daughter Caroline was born. The salt air did not agree with her, and they looked to Connecticut for a country home. According to an early memoir, Caroline wrote that her father was the one who wanted to buy what is today The Bellamy-Ferriday House. The home’s dilapidated state did not impress her mother nor her grandmother, but the Ferridays eventually decided to buy the old place, which they named “The Hay.”

Henry Ferriday did not live long enough to see his beloved country estate turned into the showpiece it is today. He died in 1914 from pneumonia. Though the loss of such a beloved partner and father was a deep wound for Eliza and her daughter, they chose to work to transform the house, install plumbing, modernize the interior, and create the lovely garden, which still delights visitors today. But between renovating her country home, scouring the Woodbury antique shops for furnishings, and raising her daughter, Eliza Ferriday led an extraordinary effort to aid a group of White Russians, aristocrats forced out of Russia, many with only the clothes on their backs.

I was inspired to write my second novel Lost Roses, a prequel to Lilac Girls, when I discovered Eliza’s dedication to the cause in a newspaper clipping, which featured a photo of young Caroline wearing a Russian kokoshnik headdress and cradling a doll. The article told how Eliza turned her elegant Manhattan apartment into a permanent bazaar from which she sold handmade items, lace, and lacquered boxes and dolls, all made by former Russian countesses and princes who were now destitute and living in Paris. Eliza sent the proceeds back to France. How could young Caroline not be inspired by her mother’s work, when she lived among it?

A visitor today will see vestiges of the Russian women Eliza helped in the lovely silver icons on the wall of Caroline’s bedroom and will also find traces throughout the house of the other ancestors Caroline came to emulate: her seven great aunts and her great grandmother Jane Eliza Newton Woolsey. Jane Eliza, who married Charles Woolsey in 1827, lost her husband tragically. While returning from New York City to Boston on the steamer Lexington one night he perished at sea. It was a terribly cold evening, the mercury at 10 degrees below zero, and floating ice filled Long Island Sound. Suddenly the alarm of fire was given as flames spread through the cotton bales in the ship’s cargo bay. Of the crew and 144 passengers, only 4 were rescued.

This terrible death forced Jane Eliza, mother of seven young daughters and expecting her eighth child, to regroup, and she moved the family to New York, where her husband’s brother Edward lived. Born in Virginia to a slave-holding family, Jane Eliza, upon witnessing a slave auction in Charleston, had vowed to fight the practice of slavery and raised her children to do the same. In the Civil War, four of her daughters served as nurses for the Sanitary Commission, and the rest of her children dedicated their time to war relief.

Five of the daughters became published authors. Jane wrote Hospital Days: Reminiscence of a Civil War Nurse. Abigail wrote a series of handbooks for hospitals, Mary wrote several anonymous, enormously successful Civil War poems, including A Rainy Day at Camp. Georgeanna’s book, Three Weeks at Gettysburg, chronicled her and her mother’s efforts to tend the wounded after the battle. Together with her husband Dr. Frank Bacon, Georgeanna went on after the war to found the Connecticut Training School for Nurses at New Haven Hospital in 1873. And Eliza and Georgeanna co-wrote My Heart Toward Home, which chronicles the family’s war efforts and includes the family’s Civil War correspondence.

Five of the daughters became published authors. Jane wrote Hospital Days: Reminiscence of a Civil War Nurse. Abigail wrote a series of handbooks for hospitals, Mary wrote several anonymous, enormously successful Civil War poems, including A Rainy Day at Camp. Georgeanna’s book, Three Weeks at Gettysburg, chronicled her and her mother’s efforts to tend the wounded after the battle. Together with her husband Dr. Frank Bacon, Georgeanna went on after the war to found the Connecticut Training School for Nurses at New Haven Hospital in 1873. And Eliza and Georgeanna co-wrote My Heart Toward Home, which chronicles the family’s war efforts and includes the family’s Civil War correspondence.

I often wonder why the women at the heart of my novels have resonated so strongly with America and the world more than two centuries later. I like to think it has something to do with the way these women lived their lives so selflessly. They had the means to do as they pleased, but they always chose to give back, to focus on the less fortunate. They didn’t do it for fame or money or political office, but rather out of kindness and compassion.

That is the wonderful legacy Caroline Ferriday inherited.

Martha Hall Kelly is the author of The New York Times bestselling novels Lilac Girls: A Novel (Ballantine Books, 2016) and Lost Roses: A Novel (Ballantine Books, 2019).

Explore!

If you enjoyed this story, receive each beautiful and informative issue to your home! SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.

Destination: Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden, Summer 2008

Caroline Ferriday: A Godmother to Ravensbruck Survivors, Winter 2011/2012

Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden

9 Main Street North, Bethlehem

Open May through October

ctlandmarks.org/properties/bellamy-ferriday-house-garden/

The Butler-McCook House, Winter 2003

Saving Hartford’s Amos Bull House, Summer 2015

City, Country, Town: Connecticut Landmarks, Summer 2010

A Love Story at the Palmer-Warner House, Fall 2019