By Susan Braeuer Dam

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2015

Read as a PDF

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

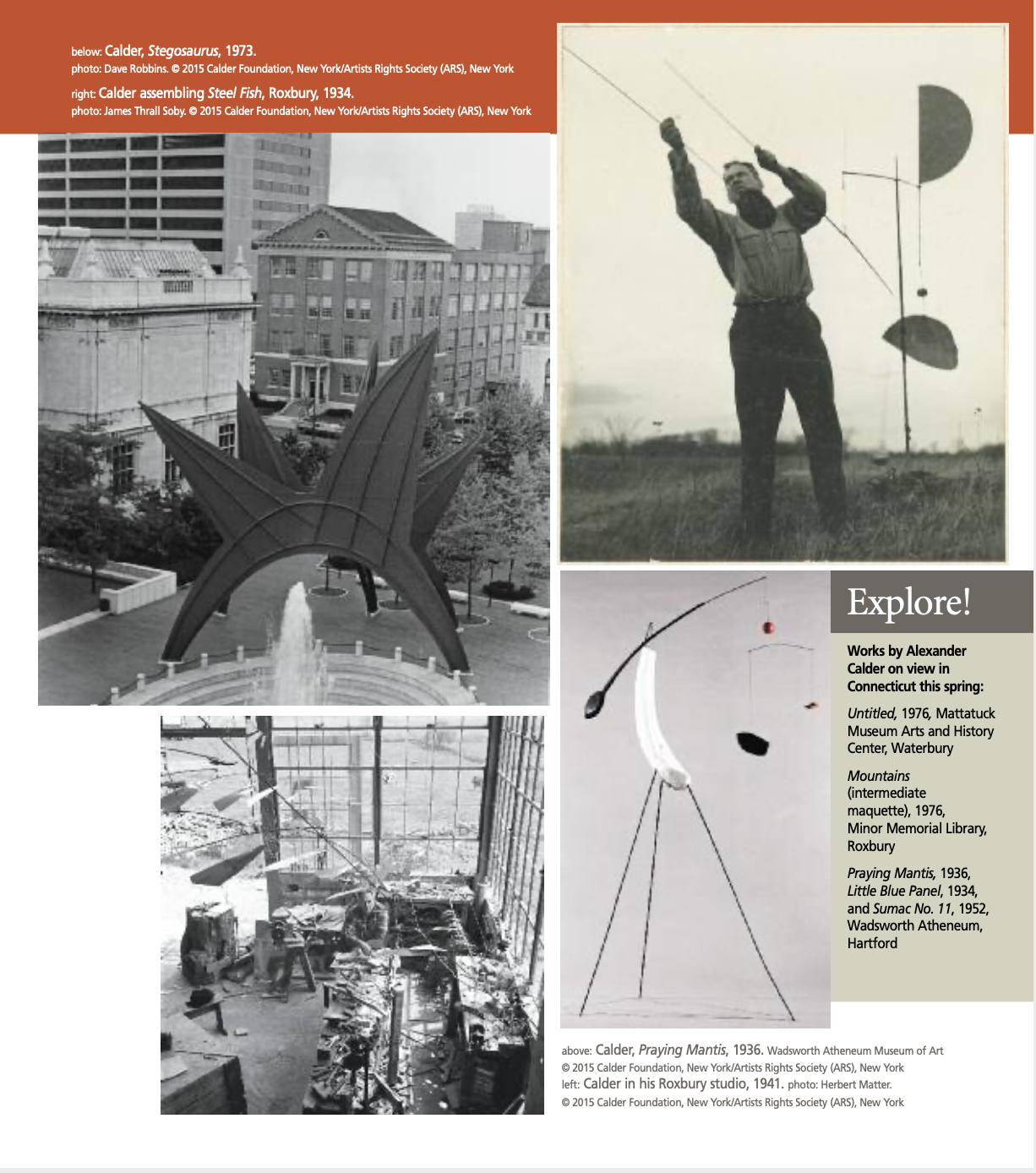

Four decades after its installation, Alexander Calder’s Stegosaurus (1973) remains a salient feature of the Hartford cityscape, situated between City Hall and the Wadsworth Atheneum. To those who venture underneath its telluric yet soaring forms, the 40-ton stabile conjures unflinching dynamism from absence, giving rise to fresh perspectives in the midst of the everyday. Although Calder’s stature as a monumental sculptor was not established until later in his career, when he would receive commissions from all over the world, it was his early projects in Roxbury, Connecticut that prompted his development of these large-scale works.

In July 1933 Calder and his wife Louisa returned to the United States from Paris, where they had lived since they were married two years earlier, with the desire to start a family. They set out to find a house in the country close to New York City (where they planned to winter). After searching in Massachusetts, along the Hudson Valley, and on Long Island, the Calders turned to Connecticut, where, as they crested the brow of a hill, they caught sight of a defunct 18th-century farmhouse in Roxbury. At once they exclaimed, “That’s it!” (In his 1966 autobiography, Calder maintained that it was he who said it first.) The 18-acre property was eventually outfitted with three Calder-made studios, and it became Calder’s headquarters after his career exploded internationally after World War II.

Before settling in Roxbury, Calder made sculptures that were intimate in scale, albeit grand in imaginative force. In 1931, after having been at work for five years on his Cirque Calder (1926–1931) and wire figures, he set abstract art in motion using cranks and motors to diversify the spatial and temporal relationships of compositional elements. That autumn, avant-garde pioneer Marcel Duchamp was mesmerized during a visit to Calder’s Montparnasse studio. It was Duchamp who suggested the appel- lation “mobile” for these works, a pun in French that means “motive” and “that which moves.” In Modern Painting and Sculpture (Berkshire Museum, 1933), Calder explained, “The esthetic value of these objects cannot be arrived at by reasoning. Familiarization is necessary.” Engaging a liveliness that transcended boundaries of established genres in art, Calder’s innovations called for unalloyed experiences in real time.

With the move to Connecticut, Calder’s urban Paris studio gave way to the verdant Roxbury countryside, and Calder’s motorized mobiles developed into wind-propelled volumes in space. In summer 1934, Calder made his first works for the outdoors; these ranged in size from five feet to nine feet tall. Red and Yellow Vane and Red, White, Black and Brass were agile constructions with mobile elements atop tripod legs of rod that could be embedded into the soil; Steel Fish was more resilient, with welded rods of a larger gauge that could tolerate forceful gales. “I have made a number of things for the open air,” Calder wrote in The Painter’s Object (Gerold Howe, 1937). “All of them react to the wind, and are like a sailing vessel in that they react best to one kind of breeze.” Within a year Calder received two private commissions for outdoor works, among them Well Sweep (1936) for the Greek-revival Farmington, Connecticut home of art collector and connoisseur James Thrall Soby.

Calder’s intellectual and intuitive praxis instigated a groundbreaking work process. By 1936, Calder realized that mlaking mistakes in large scale was as expensive as it was unproductive, so he began creating maquettes, or scale models. The first of these was a 35-inch- tall model for Devil Fish (1937), a five-and-a-half-foot-tall stabile. As he conceded in his manuscript A Propos of Measuring a Mobile (Archives of American Art, 1943), “The admission of approximation is necessary.” Depending on the viewer’s perspective, stabiles such as Devil Fish assume a new face at each turn, with elements unfolding in perpetuity as if in a state of continual becoming. By the 1960s, Calder was making intermediate-sized maquettes, too, for sculptures of a colossal scale. The actual pieces were fabricated at local Connecticut ironworks, but Calder remained intimately involved in their creation.

In Collection of the Société Anonyme (Yale, 1950), Duchamp commented on the art of his friend: “A light breeze… [starts]in motion weights, counter-weights, levers which design in mid-air their unpredictable arabesques and introduce an element of lasting surprise. The symphony is complete when color and sound join in and call on all our senses to follow the unwritten score. Pure joie de vivre. The art of Calder is the sublimation of a tree in the wind.” Indeed, Calder’s works for the open air, works such as Stegosaurus, encompass the endeavoring yet roomy idea of the sublime, communicating the flux and flow of life as they render transcendent its spaces.

Susan Braeuer Dam is director of research and publications at the Calder Foundation, where she has served as associate editor of a number of seminal publications that include Calder Jewelry (Calder Foundation, 2007), Calder: Sculptor of Air (24 ORE, 2009), and Calder by Matter (Cahiers d’Art, 2013).

Explore!

Read more about Calder in “Connecticut As a Magnet for Modern Artists,” and “Eliot Noyes Design Pioneer.”

Read more about Modernism in Connecticut and Connecticut’s Art History on our TOPICS pages.