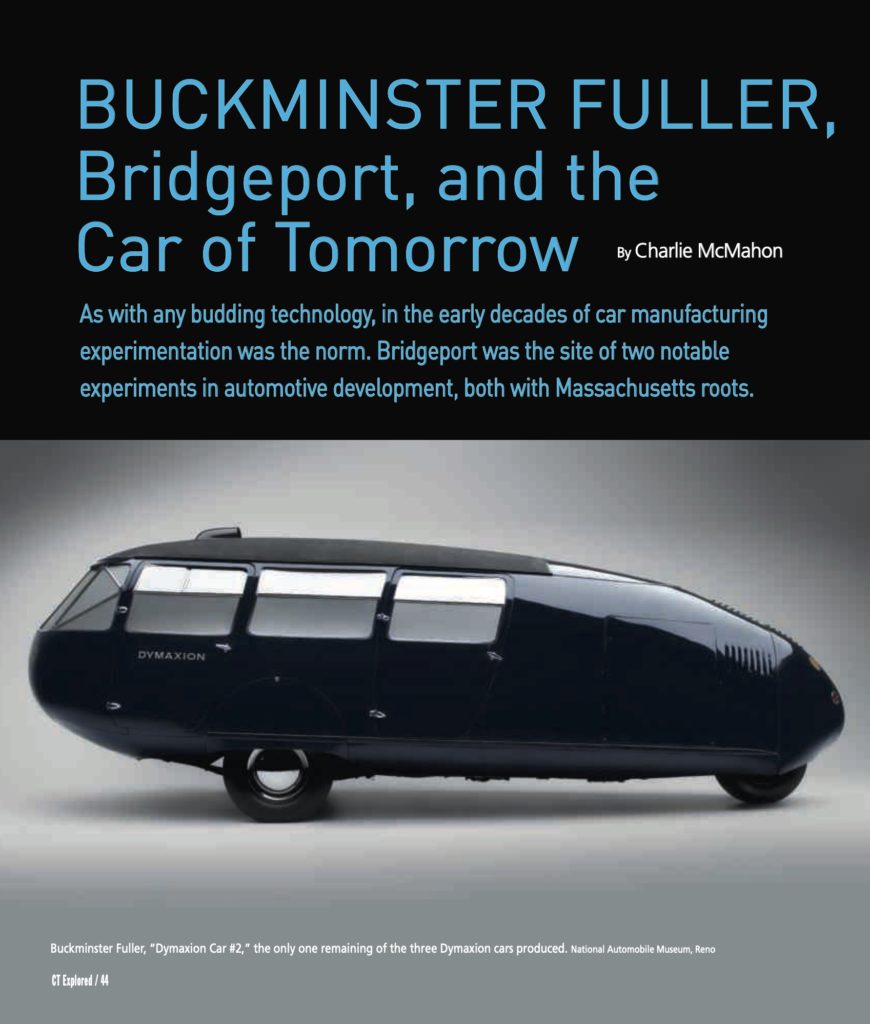

Buckminster Fuller, “Dymaxion Car #2,” the only one remaining of the three Dymaxion cars produced. National Automobile Museum, Reno, Nevada

By Charlie McMahon

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

As with any budding technology, in the early decades of car manufacturing experimentation was the norm. Bridgeport was the site of two notable experiments in automotive development, both with Massachusetts roots.

The second of these experiments was the innovative design of the brilliant polymath Buckminster Fuller. Born in 1895 in Milton, Massachusetts, Fuller sought to combine the world of aesthetics with the pursuit of futuristic, environmentally sound technology. The Buckminster Fuller Institute (bfi.org/about-fuller/biography) notes that his design philosophy of “doing more with less,” reflected his recognition of “the accelerating global trend toward the development of more efficient technology.” He found inspiration in nature and principles of the universe.

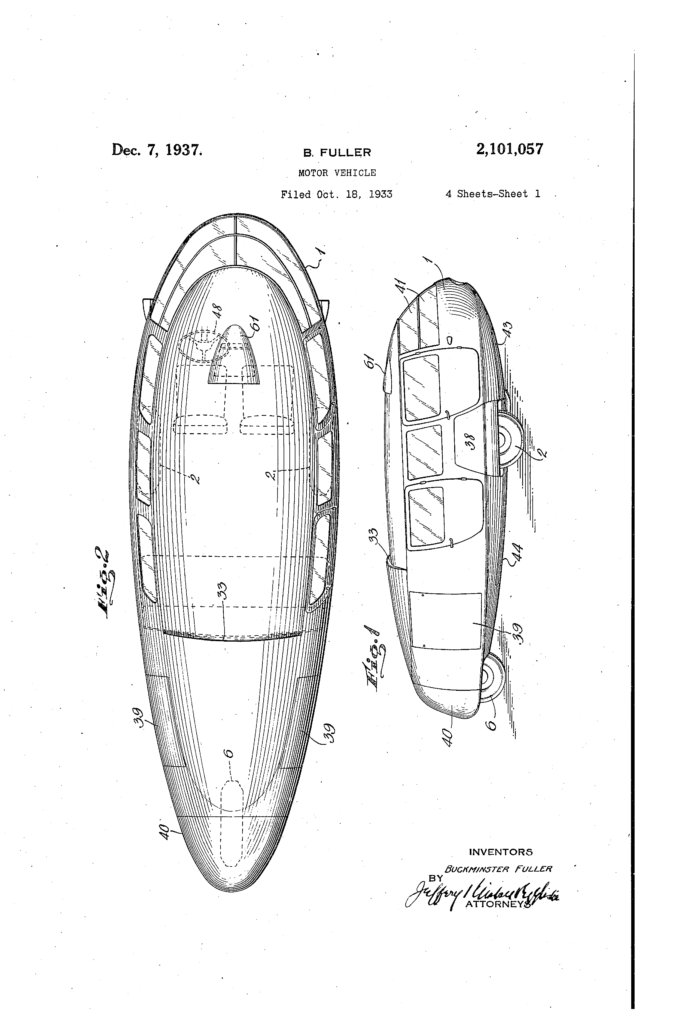

1927, though, found Fuller in the depths of despair, as the Buckminster Fuller Institute documents, due to a recent business failure. Contemplating suicide, he had an epiphany. Instead of ending his life, Fuller decided to apply his intellect and creativity to the greater service of humanity. Secluding himself in his studies, Fuller developed the idea for the Dymaxion house and the Dymaxion car, which was designed to run on alcohol. Fuller was truly ahead of his time, incorporating jet propulsion and aquatic capabilities, too, with the idea that the vehicle could function as a boat, a plane, and a car.

As Grace Glueck of The New York Times wrote on May 19, 2006, Fuller and his friend, designer Isamu Noguchi, pursued their vision undeterred by the onset of the Great Depression. They created an early prototype that incorporated the sea and air aspects of Fuller’s original idea, though these were later scrapped due to limitations in existing technology. Noguchi and Fuller decided on an aerodynamic teardrop shape that was realized when Philip Pearson, a stockbroker who had pulled out of the stock market before it crashed, invested in a set of functional prototypes.

Looking for a place to produce this marvel of a vehicle, Fuller and his team found suitable space in the shuttered Locomobile Company factory in Bridgeport. Locomobile had been founded in 1899 in Watertown, Massachusetts but relocated to Bridgeport in 1900. It initially built inexpensive steam-powered cars (fueled by kerosene or naphtha), later switching to luxury gasoline-powered cars. On its website, the Henry Ford Museum describes how, behind the wheel of a Bridgeport-made Locomobile, George Robinson steered the first American car to victory in the Vanderbilt Cup, held on Long Island, in 1906. Unfortunately, by 1929, Locomobile had gone bust. Perhaps attracted to the site’s storied spirit of ingenuity, Fuller’s team moved into the factory in 1933.

As the National Sailing Hall of Fame documents, Fuller’s first decision was to hire famed racing yacht designer William Starling Burgess to carry out the prototype construction. As documented in the Burgess Papers at the Mystic Seaport Research Center, Burgess possessed a deep knowledge of all vehicles. For instance, he built an airplane in 1909, making one of the first flights in New England. Before working with Fuller, he collaborated with the Wright Brothers.

As built, The New York Times reported on June 15, 2008, the Dymaxion prototype’s chassis contained aircraft-grade steel wrapped in an ash wood frame coated in aluminum. Fuller placed the engine in the rear of the car. This liberated the front of the vehicle, allowing it to take its idiosyncratic form. Its abundant space accommodated 12 passengers and their luggage. It also had only three wheels, allowing for more interior space—something that was very important to Fuller’s original vision.

In July 1933 Fuller debuted the Dymaxion car at Seaside Park, achieving a speed of 70 miles per hour, The (New York) Daily News reported on July 22, 1933. That fall, the Dymaxion journeyed from Bridgeport to the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago. On October 27, however, disaster struck. During a demonstration, the car flipped over twice, killing the driver and injuring two passengers, The Hartford Courant reported on October 28, 1933. What caused the crash has long been disputed. While an investigation cleared the Dymaxion of fault, the press surrounding the incident poisoned the public against the car.

For a time, Fuller continued to promote his futuristic creation. According to the Isamu Noguchi Foundation, on February 7, 1934, Noguchi and Fuller drove author and future U.S. Representative from Connecticut Clare Boothe Luce in the car to Hartford for the premiere of Gertrude Stein’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

Unfortunately, except for the three prototypes, the Dymaxion car never went into production. Bridgeport’s Dymaxion Corporation closed in 1936. Fuller’s invention of the geodesic dome in 1947 dominated the rest of his career and remains his most lasting legacy.

Charlie McMahon, a graduate of Trinity College and Central Connecticut State University, is education assistant for the Fairfield Museum and History Center.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS