By David K. Sturges

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

When Ellen Sturges submitted an application for listing her grand home on the National Register of Historic Places (to which it was added by the National Park Service in 2009), she undertook plans to restore it after decades of deterioration. That plan presented a walloping task, and the pressure of a limited budget made the prospect all the more daunting. The building’s sheer size (6,278 square feet), and architectural uniqueness would require specialty craftsmen. Despite the enormity of the project, she was committed, and, as her partner, so was I.

Ellen inherited the exceptional Cape Dutch-style house from her parents, who had 40 years earlier purchased it from its original owners, the Warner family. It was built between 1910 and 1912 by Dr. Ira DeVer Warner as a summer home and estate atop Southport’s Mill Hill, with its commanding view of Long Island Sound.

When Warner retired in 1910 as head of Intimate-apparel manufacturers Warner Brothers Company in Bridgeport, he was one of New England’s wealthiest men, according to John Warner Field’s 1990 company history. He and his brother Lucien Warner had built Warner Brothers into national manufacturing leadership with his physician’s approach to simpler, more comfortable and healthy under-apparel products for women. (See “Connecticut Shapes the Intimate Apparel Industry,” Winter 2017-2018.)

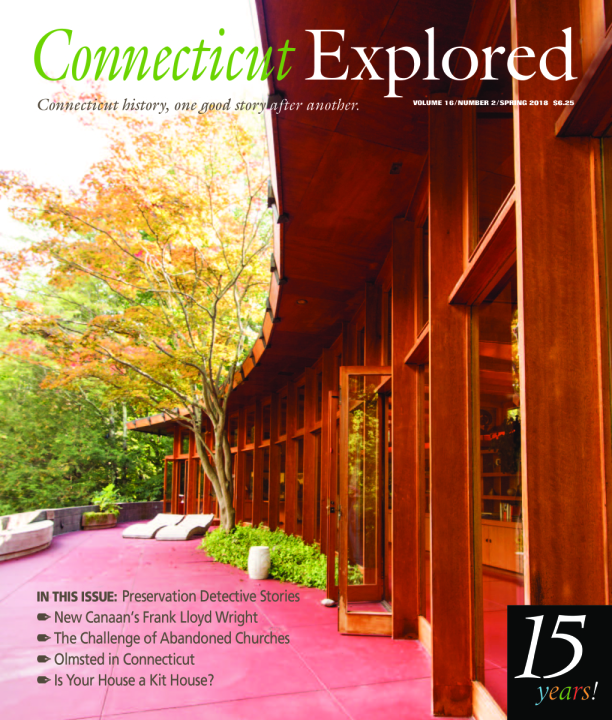

Warner patterned his house after “Groote Schuur,” Cecil J. Rhodes’s estate in Capetown, South Africa. Warner admired Rhodes, Britain’s famed empire builder and mining magnate, who had died in 1902 and willed his estate to become the prime minister’s residence of the Union of South Africa. Warner was captivated by Groote Schuur’s Cape Dutch style. He hired renowned U.S. architect Ehrick Kensett Rossiter, who combined the Cape Dutch style with his signature classic interior detail. The result was a masterpiece blend and one of Rossiter’s biggest commissions.

Warner insisted on the best of materials and on local construction labor as a means of supporting the local economy. He chose the name “Restmore” as a reflection of his advocacy of good bodily health. He neither smoked nor drank and went to bed very early. “Every hour of sleep you get before midnight,” he would declare, “is worth two following,” Field notes.

Restmore had a household staff of 15 who served the Warners and their many guests, especially John D. Rockefeller, Sr., Dr. Warner’s closest friend. Sadly, Warner’s discipline about a healthy lifestyle didn’t yield him good results. In 1913, just a year after Restmore was completed, he died of a heart attack at age 72. For the next 38 years, his widow Eva and their young son Ira lived in the house and altered it to accommodate year-round living.

Following Eva’s death in 1940, Ira subdivided the estate and sold the house in 1947 to Arthur Fuller Leeds (known as Fuller Leeds) and Muriel Read Leeds. Fuller was a banker, and Muriel was the daughter of Charles Barnum Read, a friend of the family and head of Read’s Department Store in Bridgeport. The Leeds both died in 1988, and ownership of the property passed to their daughter Ellen.

At the outset of restoration an engineering and structural analysis revealed that the house’s masonry and steel construction were sound but that exterior stucco was slowly failing. Stucco resurfacing followed by elastomeric painting was recommended for renewed durability.

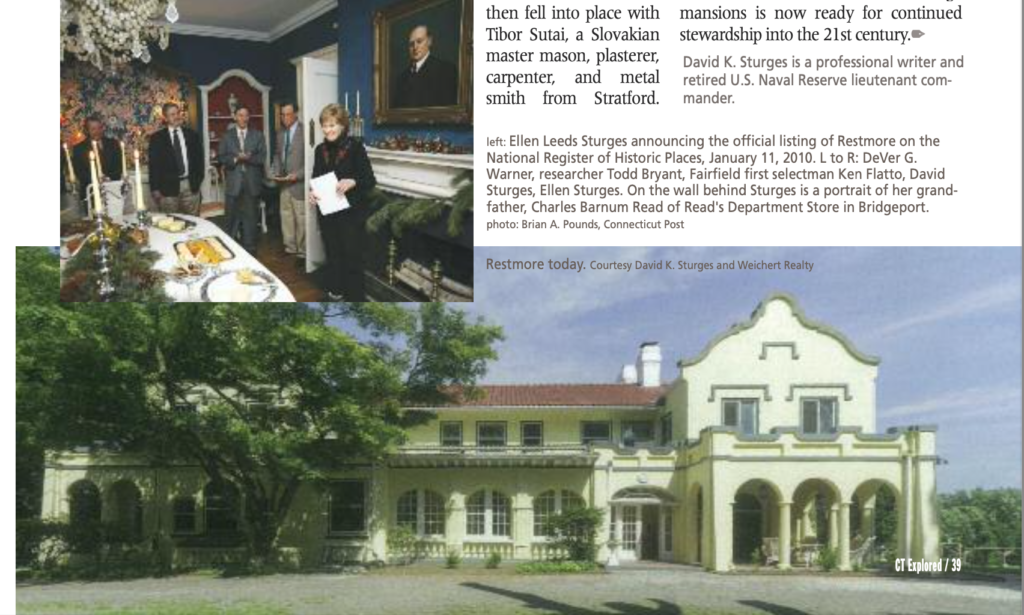

top: Ellen Leeds Sturges announcing the official listing of Restmore on the National Register of Historic Places, January 11, 2010. L to R: DeVer G. Warner, researcher Todd Bryant, Fairfield first selectman Ken Flatto, David Sturges, Ellen Sturges. On the wall behind Sturges is a portrait of her grand- father, Charles Barnum Read of Read’s Department Store in Bridgeport. photo: Brian A. Pounds, Connecticut Post; bottom: Restmore today. Courtesy David K. Sturges and Weichert Realty

Ellen and I came up with a priority- and authenticity-based restoration plan to meet National Register, state, and town historic-preservation guidelines. Fortunately, this phase was accomplished before Ellen died of cancer in 2011. I inherited the house and resolved to carry out the restoration as she wished me to do.

My first challenge was to substantiate the lore handed along by past owners. I got the first lucky break when a relocating neighbor whose ancestors were among Dr. Warner’s builders gave me a copy of Rossiter’s original architect’s specifications. They detailed the materials and methods for restoring the house the right way.

I was then able to confirm the connection with “Groote Schuur” through the Rhodes Cottage Museum of Muizenburg, South Africa. The imposing style of Groote Schuur proved visually and undeniably similar to that of Rossiter’s design for Restmore.

Contractor know-how then fell into place with Tibor Sutai, a Slovakian master mason, plasterer, carpenter, and metal smith from Stratford. Sutai did the work inside and out with exacting European professional experience. Step by step, he repaired all elevation masonry, tile roof drainage, and impervious replacement of all of Restmore’s flat porch roofs.

Contractor know-how then fell into place with Tibor Sutai, a Slovakian master mason, plasterer, carpenter, and metal smith from Stratford. Sutai did the work inside and out with exacting European professional experience. Step by step, he repaired all elevation masonry, tile roof drainage, and impervious replacement of all of Restmore’s flat porch roofs.

A third lucky break surfaced with the discovery that the house’s hardware and its wood fenestration, trim, and flooring were in good condition. With layers of old paint stripped to reveal the original materials, we found heavy, American-made brass and Douglas fir and oak wood, all 100 years old but solid. All of the interior’s 15 rooms were re-plastered and repainted, and the original moldings and trim were retained.

Restmore’s past is well illuminated by the eyewitness recall of the guests who visited Warner, including the Rockefellers, left by his son, the late Ira F. Warner, in his personal letters and journals. In all aspects of local and state heritage, one of Connecticut’s true, one-of-a-kind, Gilded Age mansions is now ready for continued stewardship into the 21st century.

David K. Sturges is a professional writer and retired U.S. Naval Reserve lieutenant commander.

Explore!

Read all of our Historic Preservation stories on our TOPICS page.

“Connecticut Shapes the Intimate-Apparel Industry,” Winter 2017-2018