Detail from an ad in The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1927. Author’s collection, Borden trademark used with permission.

By Charles Zanor

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In the 1850s, Gail Borden started what would eventually become an immensely successful milk business – later to be ably represented by Elise the Cow – from a small mill in the village of Burrville, Connecticut. It was an improbable venture, particularly because prior to Borden’s success there was no such thing as a large-scale milk business. Milk was a highly perishable product, but nobody knew why. Bacteria had not yet been discovered, so spoilage was understood only as a process of “decomposition.”

The surest way to obtain fresh, safe milk was to own a cow or have a neighbor who did. Drinking milk that was taken from poorly tended cows and distributed by unsanitary workers was a dangerous (and often lethal) proposition. Yet in spite of these risks, cow’s milk was accorded a unique and exalted nutritional status during most of the 19th century. In 1872, S.L. Goodale, Maine’s secretary of agriculture, began his monograph on Gail Borden with this rhapsody:

Milk is universally conceded to be the most perfect single article of food to be found in the whole realm of nature – the only natural product perfectly fitted to sustain life. In the best possible proportions milk combines all those flesh-forming, heat-supporting, force-yielding constituents needful to healthy growth and the development of a perfect physique.

From Meat Biscuit to Milk

In 1840, Gail Borden was living in Galveston, Texas with his wife and family. He and Penelope had moved to the territory in 1829, 16 years before it became a state. Though not yet 40 years old, Borden had developed an impressive resume. According to biographer Joe B. Frantz, Borden had been a land surveyor, a newspaper owner, and a customs collector. He owned a cattle ranch, and he was secretary for the Galveston City Company, which owned most of Galveston Island. He was also a tinkerer, although his inventions were generally more folly than substance.

Still, Borden was doing well financially and could afford to indulge his whims. Galveston had been good to him – until 1844. That year, Penelope and one of their sons died of yellow fever. Borden made a hasty and ill-considered second marriage to Augusta Stearns less than six months later. In 1846 he lost another son from an unknown cause. These events may have pushed the already impetuous and driven Borden into a project that did not merely distract him but consumed him – and his resources.

Borden developed a concoction called a “meat biscuit.” It was a hard object, the size of a meat loaf, and weighed four pounds. A traveler could pack it in his saddle bags and use it to make a soup or stew or pot pie. Some people liked it; others clearly hated it. But Borden heard only encouragement, including some from the U.S. Army and the editor of Scientific American. Surprisingly, Borden’s meat biscuit won a gold medal at the Great Exhibition of 1851 held at London’s Crystal Palace. His award, however, must have been cold comfort when he returned to New York: he had no customers (the Army had a change of heart), almost no money, and a warehouse in Texas containing 34,000 pounds of meat biscuits.

Legend has it that it was on Borden’s sea voyage back to the U.S. from England that he was ultimately inspired to find a way to preserve milk. Versions of the story vary, but they all include the assertion that the cows in the ship’s hold produced bad or insufficient milk and made the children sick.

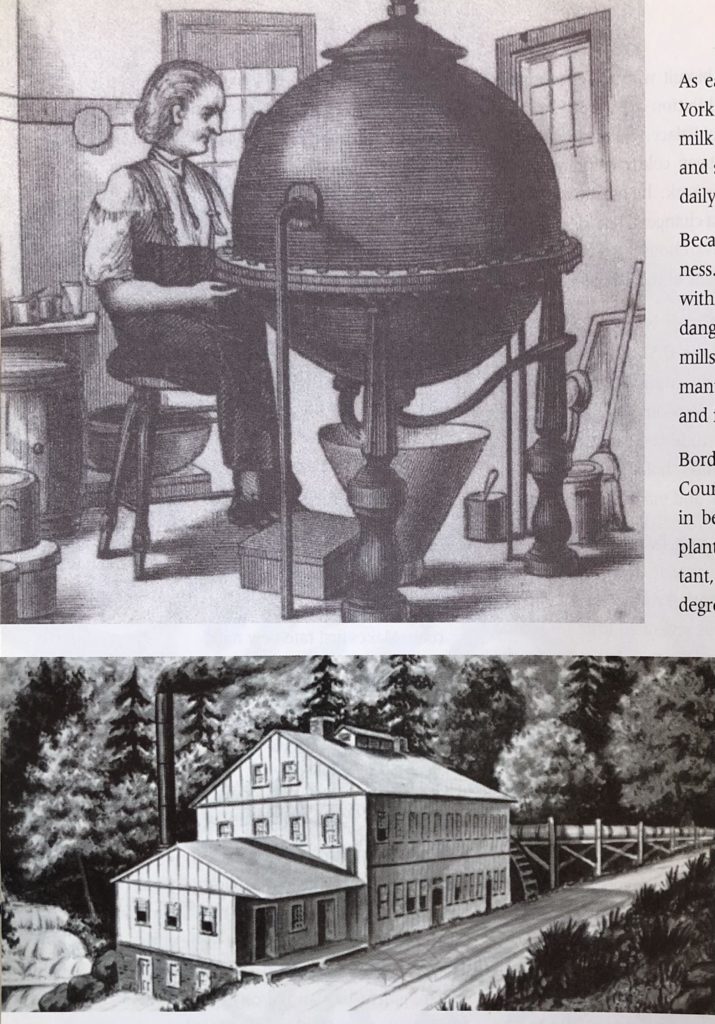

Whatever the truth behind the myth, not long after returning to New York, Borden began experimenting with ways of condensing milk. He was separated from his second wife, and, according to a letter written by one of Borden’s Texan friends, his children may have been staying at the Shaker Village in New Lebanon, New York. If so, this would help explain how Borden stumbled upon the fact that the Shakers, famous for their seeds and herbs, had been using a vacuum pan device that would be the key to condensing milk.

top: The Shakers’ vacuum pan, used to make herb extracts, from which Borden drew inspiration for his condensed milk product. The 100th Anniversary of the Founding of a Community, Almanac for 1888. Shaker Museum and Library, Old Chatham, New York. bottom: Borden’s first factory, located in Burrville, Connecticut. From Gail Borden, Dairyman to a Nation, Joe B. Frantz, University of Oklahoma Press, 1951, p. 35, used with permission.

The Shakers were best known as a religious group whose members were committed to a celibate, communal life style centered on work and religious observance. [See “Enfield’s Shaker Legacy,” Summer 2005.] The fact that Borden was allowed into the heart of their work area signaled a highly unusual relationship; the Shakers did not brook much interference from “the world’s people.” Borden was, by all accounts, a nonstop talker, and maybe he just wore the Shakers down. More likely, however, he won them over.

A journal entry made by an unidentified Shaker in June 1853 sheds light on Borden’s relationship with the community (punctuation added for clarity):

Also a man here from Texas name [sic]Borden. Inventor of patent meat biscuit for sea voyages. Also inventor of patent milk extract. Wants our folks to take up the business of making. Be kind of an agent for him. Does down a few gallons of milk in our Laboratory this eve. Pays $7 & half dollars for the milk & privilege. The process as I understand consists in boiling away all the watery principle from the milk. Bottle it up & twill keep forever if you don’t throw it away. Whenever you want it to use add 3 fourths hot water and let it cool. Makes first rate new milk!

The Shakers apparently did not take up Borden’s proposal, but that same year Borden submitted a patent application for a process that used a vacuum pan to condense milk. He was granted the patent three years later, and in the summer of 1856 he moved his equipment into an old carriage shop in Wolcottville (now Torrington), Connecticut. Since he was broke, he did all this on borrowed money, which he quickly spent. After only one month he closed the operation and went to Texas to try to raise capital.

He came back to Connecticut in 1857 and this time found a better setting for his enterprise in an empty mill in Burrville. Just five miles up the road from Wolcottville, it is traditionally recognized as the official launching site of Borden’s Condensed Milk.

He and a small staff worked hard to manufacture the new product. Borden traveled to New York City to sell it door to door. He had little choice. The neighboring farmers had no need for the condensed milk, as fresh milk was plentiful and mostly used to make butter and cheese rather than to drink. Milk, ironically, was a city beverage.

As early as 1806, according to dairy historian Ralph Selitzer, New York City’s streets were replete with men carrying two buckets of milk on a shoulder yoke and crying “Meeleck. Come!” Housewives and servants, pitchers in hands, would open their doors to get their daily supply of what would soon be deemed nature’s perfect food.

Because of its perishability, milk was primarily a home-delivery business. By 1830 distribution by horse and wagon replaced the man with buckets, but the product was often a terribly inferior (and often dangerous) one. Much of New York City’s milk came from “swill” mills – huge barns attached to breweries and distilleries where as many as 500 to 1,000 cows were shackled in crowded, dirty stalls and fed the mash left over from making whiskey or beer.

Borden’s condensed milk product from the farms of Litchfield County, though not fresh, was far superior. He was ahead of his time in being an absolute purist about sanitary conditions both in the plant and on the farms that supplied him with milk. Equally important, Borden’s condensing process occurred in a vacuum at 136 degrees Fahrenheit, thereby subjecting the milk to a form of pasteurization. Borden could not possibly have known this in 1857, of course – he was just trying to remove most the water from milk without changing its taste.(Coincidentally, it was in 1857 that Louis Pasteur published his research on fermentation in milk, but this was just a gateway study for his real interests: wine, followed by vinegar and beer. A scientifically based, commercially viable, whole milk pasteurization process was still a quarter century away.)

Later, when Borden added granulated sugar to condensed milk before sealing it in cans, he was taking yet another step in the preservation process without fully understanding it: sugar inhibits the growth of bacteria in milk. All in all, he was offering the public a fine product.

Still, Borden’s Condensed Milk wasn’t what people were used to, and it was a hard sell. In addition, the rocky economy of 1857 made it tough for even established businesses to survive. Borden was soon in financial trouble again. In the fall of 1857, hobbled with debt, facing suits brought by some of his creditors, and lacking money to pay farmers for the milk he needed to manufacture his product, Borden suspended operations at the Burrville plant.

Hat in hand, Borden headed to New York to face his financial partners, who had no intentions of further supporting his failing business. On the train, he sat next to a man named Jeremiah Milbank, who was on his way back to the city after visiting his in-laws in Greenwich. Milbank was a wholesale grocer and an investor. He was a successful businessman; Borden was not.

Listening to Borden talk and talk, Milbank saw the potential in his product. By February 1858 Borden was back in Burrville and back in business. Milbank had settled all the debts and was working to procure the five-eighths patent rights Borden had sold for a relative pittance along the way. Milbank and Borden agreed to be equal partners in the business.

Sales were slow but steadily growing, helped no doubt by an advertisement in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper that appeared during a time when the newspaper was railing against “swill milk” killing babies in New York. Borden was keeping his head above water. It wouldn’t last long.

In 1860, he had a dust-up with mill owner Milo Burr about the rent. Borden was irritated by the encounter and, in classic Borden style, decided almost immediately that he wanted to move the company to Wassaic, New York. Milbank thought the move was impulsive and not justified by the company’s balance sheet. He withheld his approval and financial support. Borden, whose memory of his recent financial disaster was incredibly short, went ahead anyhow. He also chose this time to embark on his third marriage (though the resolution of his second marriage is unknown), to the former Emeline Eunice Church.

Once in Wassaic, Borden repeated history by borrowing money wherever and however he could in order to get his operation moving. Milbank sat back and waited while Borden went deeper and deeper into debt. A great tragedy for the nation – and its business environment – gave Borden his big break.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Milbank understood that the Union Army would need to eat. A product that had a long shelf life and traveled well would be very attractive. Once again, Milbank bailed Borden out financially and infused enough new money into the business to upgrade its facilities and prepare for a massive increase in production. It didn’t take long for the Army’s first order to come into the company’s New York City office, and it was a big one: 500 pounds (approximately 1,400 quarts) of condensed milk.

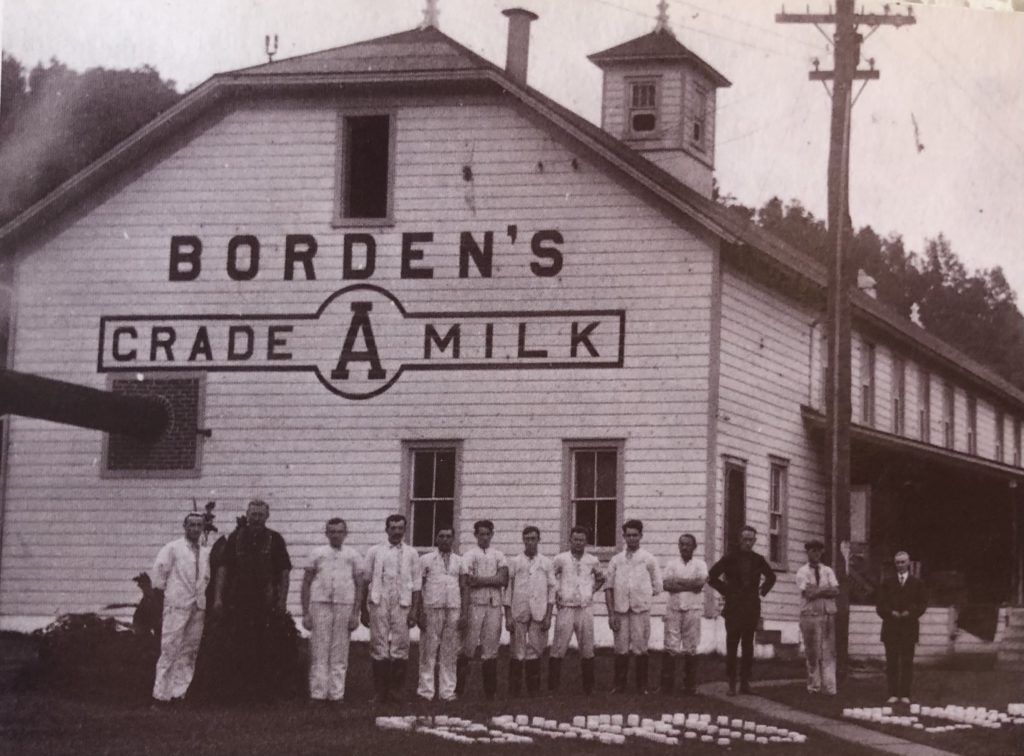

The staff at Borden’s Country Bottled Milk Station No. 71 in Washington Depot, Connecticut, 1917. Gunn Memorial Library & Museum. photo: Joseph West

In the summer of 1862, the company was averaging more than 16,000 quarts a month. A year later Borden was turning out 14,000 quarts a day. The troops appeared to be drinking the milk nonstop and New York Tribune war correspondent Charles Page was sending back dispatches singing its praises.

In 1863, Borden came back to Connecticut and opened another condensery in Winsted, about five miles from the company’s official birthplace. Three years later, in 1866, Borden changed the product’s name. At least one other company had been using the name Borden on its labels. To distinguish his product, he registered a new trademark: Borden’s Eagle Brand Condensed Milk. The first cans produced with the American eagle on the label rolled out of the Winsted plant. Although the operation in Winsted produced as many as 6,000 quarts a day, it was difficult getting local farmers to provide enough milk to meet an ever-increasing demand. With two other plants in New York each achieving daily productions of 15,000 quarts or more, the Winsted condensery wasn’t keeping up, and the plant closed December 1866.

When the Civil War ended, business dropped dramatically, and 1867 looked like it might be a very rough year until a huge order for $20,000 worth of condensed milk came in from a brand new market: Australia. The company was back on its feet.

Gail Borden and Jeremiah Milbank died within 10 years of each other, Borden in 1874, Milbank in 1884. But business was good, and it only got better as the century drew to a close. Despite the loss of its two founders, the company remained a family business: Borden’s son, John Gail Borden, became president, and Milbank’s son, Joseph Milbank, became partner.

The company had branched out into the fresh (or “fluid”) milk business in 1875 and 10 years later became the first dairy company to put milk in bottles. By 1899 the company was ready to take another big step: the family business was reorganized as The Borden’s Condensed Milk Company, a New Jersey corporation with 66 stockholders and 200,000 shares of stock valued at $100 each, for a total market capitalization of $20 million. That move set the stage for the company to become one of the giant food corporations that dominated the 20th century and changed the way Americans thought about and consumed food.

By the century’s turn, Borden’s had facilities in 18 towns in New York, New Jersey, Illinois, and Ontario, Canada. In 1901 they added Litchfield County, Connecticut to the list. A group of business leaders in the small town of Canaan recognized that the company would provide a strong financial base for the community, which sat at the northernmost point of Connecticut’s Housatonic River Valley. They contributed private funds to buy some land near the railroad station, and they enticed the company to build there.

The location was perfect for Borden’s Country Bottled Milk Station No. 47. The railroad junction provided relatively easy access to New York, and there were dozens of dairy farms in the surrounding area. In 1910, Borden’s Country Bottled Milk Station No. 71 was built at Washington Depot, another Housatonic Valley town.

above: Ad in The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1927. Author’s collection, Borden Trademark used with permission. below: Elsie the Cow’s live appearance at the 1939 World’s Fair, where she was portrayed by a real cow, outdrew every other exhibit. Courtesy of Elizabeth Knauff, Borden and Elsie’s Trademarks and Elsie character used with permission

By the early 1930s, with four new automatic fillers, cappers, and crimpers, the Canaan plant was bottling 7,200 quarts of milk an hour – enough to fill five refrigerated railroad cars that pulled into the station at 1:15 p.m. to transport the milk to Stamford, New Rochelle, and New York City.

The company sold the Washington Depot plant in 1930, leaving the Canaan plant and two collection stations in the valley at Lime Rock and Cornwall Bridge. Cornwall Bridge farmers would cart in their 40-quart cans of milk, and Earl Thompson and two helpers would put them on ice until the milk train arrived in the afternoon. By the 1930s, Thompson had a big tank that held the milk. He still had to wrestle with the 100-pound cans of milk, but only had to get them as far as the scale and tank, where the milk was kept cold. By then, the old milk train was also gone. Instead, a tanker truck came later in the day to haul the loose milk to the city.

The truck was a sign of the modernizing that would come with the 20th century, but in some ways the milk business marched to its own drummer. Borden’s Mitchell Dairy in Bridgeport, for example, did not retire the horse-drawn milk wagon distribution system until 1946. The delivery of milk was then, and continues to be, a stubbornly local enterprise. Fresh milk has always been farmed, packaged, and distributed within areas referred to as region milksheds.

The Borden Company (as it became known in 1919) was able to achieve national dominance in the fluid milk market not only by building bottling plants in different geographical regions but also by acquiring smaller companies along the way. Moreover, these acquisitions allowed them to rapidly diversify their product line. In the late 1920s, Borden purchased more than 200 companies and expanded its offerings to include ice cream, cheese, mincemeat, powdered milk, and adhesives. The technology behind powdered milk led to the development of instant coffee and coffee creamer during the 1940s. Adhesives (such as Elmer’s Glue) and other chemical products that were added later became a major source of revenue and profits for the company.

Borden also secured a place in advertising history with the introduction of its brand image, Elsie the Cow, in the 1930s. Elsie, a cartoon character cooked up by the advertising department, did not become famous until she was given a voice on the radio. Then, at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Elsie made a live appearance. According to The Saturday Evening Post, she outdrew every other exhibit during her 1940 season at the Fair. Her popularity remained high during the ensuing decades.

Borden’s enduring icon, Elsie the Cow, continues to grace products now made by the J.M. Smucker Company. Author’s collection, Borden and Elsie’s Trademarks and Elsie character used with permission

By 1990 Borden was the largest dairy company in the nation and was represented by one of the country’s best-known images (Advertising Age later named Elsie one of the top 10 icons of the 20th century). Ironically, Borden’s size, its product diversity, and its undervalued stock price made the company a target for takeover, and it was brought by Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts in 1995. KKR, whose earlier takeover of RJR Nabisco was chronicled by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar in Barbarians at the Gate, bought up all of Borden and then sold it off piece by piece.

While there is no longer a Borden Company, the Borden name and the Elsie trademark are still in use: they are licensed to various companies across the country, and the public continues to purchase products with Elsie on the label. Here in Connecticut, cans of Borden’s Eagle Brand Sweetened Condensed Milk are still on the supermarket shelves. Until recently the product was made by Eagle Family Foods of Ohio, but in May that company was bought by the J.M. Smucker Company. Smucker’s will continue to make the product (with Elsie on the can) that loyal customers have used for years to make cheesecakes, custard pies, fudge, and other desserts.

Charles Zanor is a practicing psychologist in West Springfield, Massachusetts.

Explore!

Read more stories from the Fall 2007 issue.

Read more stories about products made and invented in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories about food history on our TOPICS page.

Subscribe to receive every issue!