Lt. Benjamin Foulois (l) and the Wright Company’s Philip Parmelee flew early reconnaissance flights on the Texas-Mexico border, 1911. Library of Congress

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

Benjamin Delahauf Foulois was born on December 9, 1879 in the small town of Washington, Connecticut, the second son of parents who had emigrated from France. His father was a plumber, and young Foulois seemed destined for a career in the family business. Foulois stood only 5 foot 5 inches tall but was an outdoorsman and avid adventure seeker who excelled on the baseball and football fields. Many town natives left accounts of his heroics on the baseball diamond, marveling at his ambidextrous abilities to throw, hit the ball much farther than was typical of players his size, and jump clear over a defender attempting to tag him out in the town’s annual 4th of July baseball game. These local accounts serve as the unofficial beginning of the hometown hero legend that accompanied the life of Benjamin Foulois.

In 1893, in a last-ditch effort to take his education seriously, Foulois began attending the Gunnery School in Washington. He was never a very interested student, and as his family’s plumbing business was booming, he decided to drop out of school and become a plumber. The itch for adventure, however, soon took hold. With courage and legacy on his mind, in 1896 Foulois hopped on his bicycle and rode it to New York City, around 85 or 90 miles, to enlist in the U.S. Army. He enlisted under his brother Will’s name because, at age 17, he was too young to do so himself. Thus began an illustrious military career that spanned almost 40 years and an involvement in American military aviation that continued long after his retirement.

Foulois first saw active duty in the Spanish American War, fighting in Puerto Rico as an enlisted private in the army. After returning home and still feeling a need for adventure, he re-enlisted as a sergeant and fought in the Philippine American War from 1899 to 1902. He showed extreme bravery and courage and quickly rose through the ranks, earning praise for how well prepared his unit was and amassing a large collection of medals.

Despite his lack of a high-school diploma and his origins as an enlisted man, he went to officer training school in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. According to his autobiography and diaries, Foulois contemplated the possibilities of the airplane and hot air balloons and how they could alter military tactics, writing his thesis about the possible uses of military aviation.

After officer training school, in 1909, Foulois was sent to College Park, Maryland to receive flight instruction from Wilbur and Orville Wright. He received only 27 hours of instruction before being sent to Fort Sam Houston in Texas with simple instructions: Teach himself how to fly. He would become an aviation pioneer, flying more than 100 miles nonstop in 1911, testing the use of radio in flight, commanding a tactical air unit in 1914, and using an aircraft in a combat operation during the Pancho Villa campaign in Mexico in 1916 [See page xx.]. He became the chief of the U.S. Air Service as part of the AEF First Army, one of the predecessors to the air force, in 1918.

During World War I, he worked with General Billy Mitchell to learn about the aerodynamic advancements of the Germans and French. At this point, the Germans and the French had surpassed the Americans in flight, possessing planes capable of much higher speeds, greater carrying capacity, and far heightened stealth. As peers on General Pershing’s staff, Mitchell and Foulois might have changed that, but they instead became rivals: Mitchell didn’t respect Foulois’s lack of education, and Foulois didn’t respect Mitchell’s lack of combat experience. Eventually the command of the tactical air unit was split, allowing both Foulois and Mitchell to contribute greatly to the war effort.

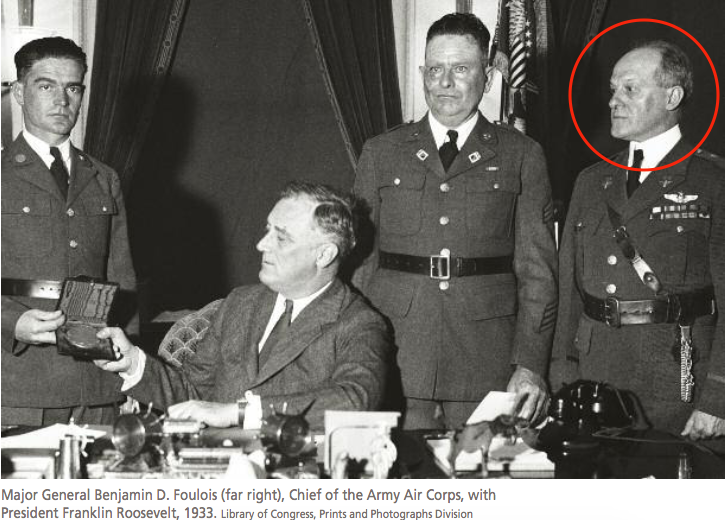

Foulois was appointed chief of the U.S. Army Air Corps as a three-star general in 1931. He convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to allow the air corps to run the mail service. He was also a close friend of General Douglas MacArthur. Foulois received some heat over deaths while carrying the mail and was forced to retire, an event that General MacArthur was adamantly against. Foulois retired to Ventnor City, New Jersey and toured the country speaking about military aviation and airpower. He was essential to the creation of the U.S. Air Force and sat on the air force’s first board of directors.

At the time of his death, on April 25, 1967, the small-town plumber’s dropout son had risen to the highest levels of achievement in the United States Armed Forces. Foulois chose to forego burial in Arlington National Cemetery, where he would have received a large monument, to come home to Washington, Connecticut, where he is buried in the Washington Town Green cemetery.

Thomas Burger is a graduate of the Gunnery School in Washington, Connecticut and a history major at Indiana University.