Unless otherwise noted, all images from the Real Art Ways Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

By Will K. Wilkins

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2017

A couple of years ago I dropped into an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City and, in a survey of performance art of the 1970s, saw a video of Mike Smith performing in downtown Hartford. Smith’s character Baby Ikki (the artist in a diaper and baby clothing) had been taped wandering into traffic and being led away by a befuddled policeman. This is not exactly the image of Hartford that likely comes to mind for most people.

In the mid-1970s downtown Hartford came alive with artistic exploration and innovation. Baby boomers were coming of age, affordable space was available in older buildings, and creative energy, much of it generated by young artists and musicians with some connection to the Hartford Art School or the Hartt School, was in the air.

Boomers had been influenced by the civil-rights movement and the anti-war movement. Change was seen as possible, and there was a sense among many that the culture would benefit from fresh organizations and enterprises that reflected the values and interests of a new generation. Real Art Ways, Peace Train, Sidewalk, Artworks Gallery, Company One, the Craftery Gallery, and the Artists Collective were all places where innovation and new perspectives were welcomed and encouraged.

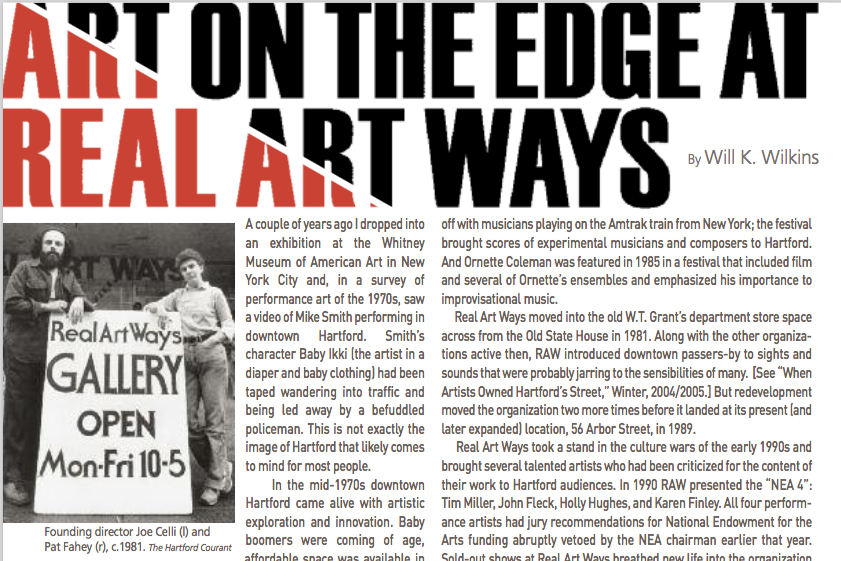

Real Art Ways, founded in 1975, saw itself very much as the “avant-garde” wing of these new efforts. And, indeed, the organization’s presentations gave a Hartford a platform that supported forward-thinking visual artists, composers and musicians, performers, writers, and film and video artists. Building owner Henry Zachs provided the first low-cost space on Asylum Street that allowed Real Art Ways to get a foothold.

Notable artists presented early on by Real Art Ways included composer John Cage. His “Empty Words,” presented in 1981, was an all-night concert, available to National Public Radio outlets nationwide. In 1984 RAW hosted New Music America, a multi-day national festival that kicked off with musicians playing on the Amtrak train from New York; the festival brought scores of experimental musicians and composers to Hartford. And Ornette Coleman was featured in 1985 in a festival that included film and several of Ornette’s ensembles and emphasized his importance to improvisational music.

Real Art Ways moved into the old W.T. Grant’s department store space across from the Old State House in 1981. Along with the other organizations active then, RAW introduced downtown passers-by to sights and sounds that were probably jarring to the sensibilities of many. [See “When Artists Owned Hartford’s Street,” Vol. 3, #1.] But redevelopment moved the organization two more times before it landed at its present (and later expanded) location, 56 Arbor Street, in 1989.

Unless otherwise noted, all images from the Real Art Ways Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

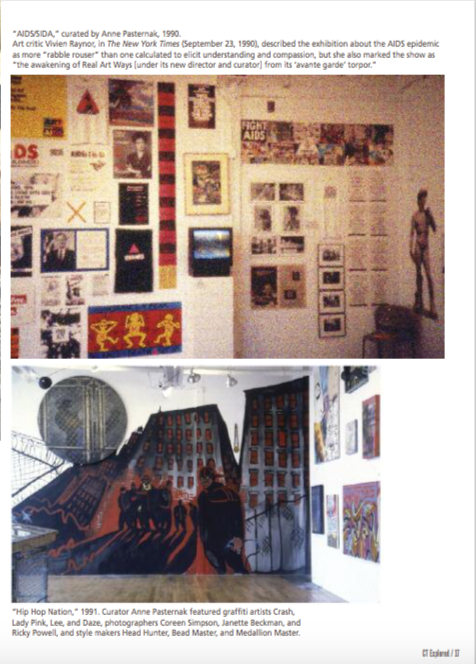

Real Art Ways took a stand in the culture wars of the early 1990s and brought several talented artists who had been criticized for the content of their work to Hartford audiences. In 1990 RAW presented the “NEA 4”: Tim Miller, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Karen Finley. All four performance artists had jury recommendations for National Endowment for the Arts funding abruptly vetoed by the NEA chairman earlier that year. Sold-out shows at Real Art Ways breathed new life into the organization, and in particular generated support from the LGBT community.

Unless otherwise noted, all images from the Real Art Ways Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

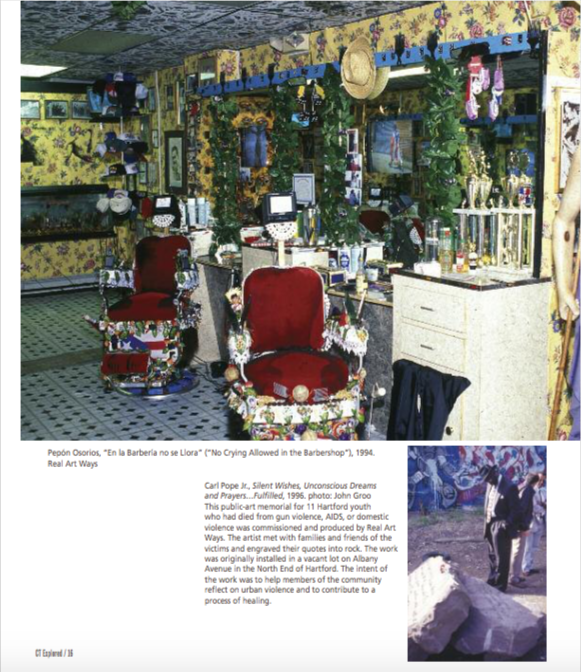

Real Art Ways commissioned and produced several public art projects in Hartford neighborhoods, including, in 1991, Mel Chin’s “Ghost,” an evocation of Hartford’s first African-American congregation (now Faith Congregational Church) and Pepón Osorio’s “En la Barbería no se Llora” (“No Crying Allowed in the Barbershop”) in 1994, a street-level installation of the artist’s over-the-top version of an all-male Puerto Rican barbershop, installed on Hartford’s Park Street.

Unless otherwise noted, all images from the Real Art Ways Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Real Art Ways is a unique Connecticut institution, where art and community are intertwined. And RAW itself can be seen as an art installation. Where else in the country can you find a welcoming place, in a city neighborhood, that presents new and innovative independent film, gallery exhibitions, social events, concerts, story telling, and spoken word—and brings together audiences from different backgrounds and perspectives?

For all the breakthrough performances and artists that have been presented here, it is the organization itself that might be the most significant breakthrough of all.

Will K. Wilkins is executive director of Real Art Ways.

Explore!

Real Art Ways

56 Arbor Street, Hartford

The archives of Real Art Ways are housed at the Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library. For more information visit hhc2.hplct.org/realartways.html.