Ann Petry, c. 1953, taken around the time The Narrows, her third and final novel for adults, was published. Courtesy Liz Petry

By Elisabeth Petry

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Best-selling writer Ann Petry explored many facets of the Black experience in her fiction. Born in Saybrook (now Old Saybrook), Connecticut just after the turn of the 20th century, she brought to her work the sensibility of someone who grew up as part of a tiny minority and who saw the horrors of ghetto living during the nine years she spent in New York City. Her novel The Narrows (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1953) offers a commentary on the racial, class, and economic conflicts that lie beneath the surface in mid-century New England. It is the story of a doomed love affair between a handsome, brilliant young Black man and a rich, white, married woman. Drawing on an incident that occurred in Hawaii in the 1930s, Petry set her novel in a fictional port city in Connecticut (based partly on Hartford and New London) just after World War II. Petry has “Cesar the writing man” scrawl the novel’s theme in chalk on the sidewalk: “Is there anything whereof it may be said, See, this is new? It hath been already of old time, which was before us.”

Early in the story, Camilla (Camilo) Treadway Sheffield, the married heiress to a gun-manufacturing fortune, wanders down to the dock in the Black section of Monmouth. She becomes frightened and runs into the arms of a man she cannot see clearly in the dark and fog. Lincoln Williams (Link) has returned to the city of his birth from a four-year stint in the navy. Despite his Dartmouth education, the only job he can find is behind the bar at the Last Chance, a dive run by the local Black crime kingpin. Link and Camilo fall in love, but when her mother and husband learn of the affair, they exact their revenge.

Much of the story unfolds in the ghetto called The Narrows, where the orphan Link has grown up in the household of a couple he calls Aunt Abbie and Uncle Theodore. The place and the people, including Abbie Crunch, the kingpin Bill Hod, and Abbie’s tenant Malcolm Powther, butler to Camilo’s mother, embody the range of Black experience. Link can easily navigate Black and white worlds. Abbie wants to be white. Hod is a Black-power advocate. Powther stands on propriety as he sees it.

With its cramped living quarters and undesirable spaces, The Narrows becomes a character in the novel. It goes by a variety of names, among them The Bottom, Little Harlem, Dark Town, and N—-rtown, common terms for ghettoes throughout the country. Petry fashioned The Narrows after the Black sections of Hartford and New London. Monmouth resembles Hartford, which thrived on gun manufacture and attracted successive waves of immigrants and was, as Petry noted in her journal and personal papers, “half-city, half-suburban,” with “residences brick, many of them frame, almost all with some kind of backyard, even if only a scrap, streets fairly wide.” New London, with its waterfront catering to sailors, was by the 1940s “a curious place—retrograde—I think—going backward not forward—subject to certain kinds of forces” because of the long decline of the whaling industry.

The effect The Narrows has on people can be corrosive. The people are “bobtail, ragtail, flotsam and jetsam,” Petry writes in The Narrows. It is a place of inferior goods, of defeated expectations, of many dreams deferred. Abbie’s friend the funeral director Frances Jackson, who aspired to practice medicine, has learned to live with the humiliation of being called “[t]hat n—-r woman undertaker” by the Irish casket maker.

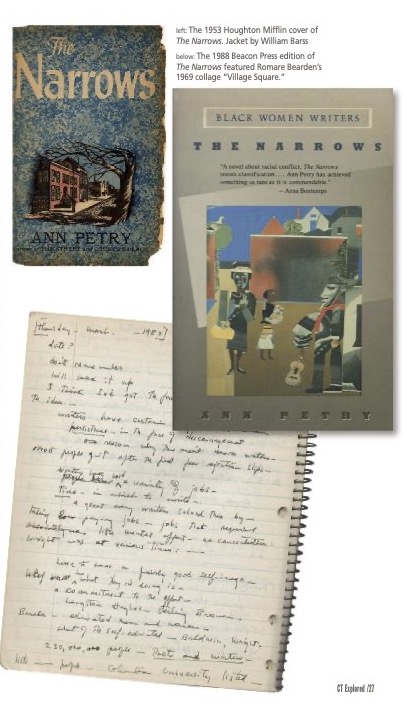

top left: The 1953 Houghton Mifflin cover of The Narrows. Jacket by William Barss. top right: The 1988 Beacon Press edition of The Narrows featured Romare Bearden’s 1969 collage “Village Square.” bottom: A page from Ann Petry’s journal musing on the nature of writing, notes for a lecture about author Richard Wright that she gave at Yale, March 24, 1982. Courtesy Liz Petry

A stranger to Monmouth asks if they have just buried his brother in a colored cemetery. Assistant funeral director Howard Thomas (who wanted to be a lawyer), replies, “No . . . but in another ten years or so we’ll have that, too. We’ve got two practically colored schools and we’ve got a separate place for the colored to live, and separate places for them to go to church, and it won’t be long before we’ll work up to a separate place for the colored to lie in after they’re dead. . . . Then you’ll feel right at home here in Monmouth. It’ll be just like Georgia except for the climate.”

Each character encounters a different facet of the color line, reflecting Petry’s own experiences growing up and living in Connecticut. As Petry did, Link suffers because of a racist teacher. Miss Dwight has Link play Sambo in a minstrel show. Petry’s sixth-grade teacher made her read the part of Jupiter, the former slave and “elderly negro” in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Gold-Bug.” Poe rendered Jupiter’s words in the broadest dialect, “dey” for “they” and “goole” for “gold.” As she noted in her journal, Petry felt mortified as her classmates laughed at her.

Another teacher restored her self-esteem, and Petry gives Link that uplift as well. Petry’s teacher was Harold White, the basis for the character Robert Watson White. Harold White noticed that she seemed to duck and frown whenever the issue of slavery arose. He had her read widely and encouraged her to talk about the subject. He convinced her that “slavery was not my shame.” The fictional Mr. White gives Link a passion for history that contributes to his downfall. He reflects that he knows too much about “the various hells” that began when the first Blacks arrived on a Dutch slaver in 1619.

The irony was that in 1964, Petry stopped Harold White’s wife from putting blackface on my white schoolmates for a high-school production of Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding. My mother was so protective that I knew nothing of this incident until I read her journal. She always shielded me from the soul-destroying racism that she encountered.

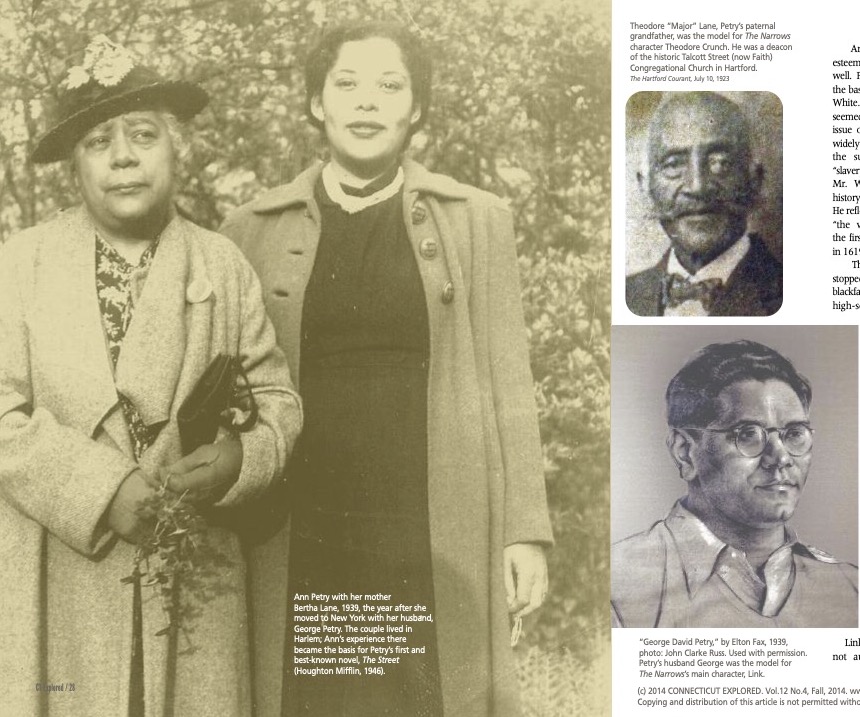

While Petry used her own experience in writing about Link’s early life, her models for the adult Link were her husband, George Petry, and a friend, Carl Offord. My father, like Link, had stunning good looks, played football, attended an Ivy League school, and was intellectually overqualified for the available jobs. Offord was a newspaper publisher and writer whose 1943 novel The White Face concerned a Black man driven by hatred to violence against whites. Both men served in World War II and grew up without their mothers.

Link suffers the sting of racism but does not automatically assume that white people mean danger. Unsure whether Camilo is white or “high yaller,” he watches the waiter Bug Eyes, who grew up in the South. As he sees Camilo from a distance, Bug Eyes is smiling, friendly. He looks again, and his face becomes hostile, “complex and dangerous.” When he realizes she is white, his defenses go up against the expected attack. Link draws his own conclusion based on a different cue. Camilo lets him drive her Cadillac and comments, “Oh, you’ve driven one of these before.” Link thinks, “Oh, you’ve held a tennis racket before, oh, you’ve worn shoes before. . . . That surprised condescension in the voice is an unmistakable characteristic of the Caucasian, a special characteristic of the female Caucasian.” Petry has Link recognize the tone that no Black woman, however pale, would use in addressing another of her own race.

Petry draws Abbie as someone who wants to be white. Though struggling financially, she is ever the patrician: “[S]hort, plump, … expressive-eyed. … She had New England aristocrat written all over her, in the straight back, … in the Yankee twang of her speech.” That description also fit Petry’s mother, Bertha James Lane. The similarities do not end there. Both the character and the woman became the first Black president of the local Women’s Christian Temperance Union. This position gives Abbie a degree of superiority over the white members of the organization. Her attitude carries over into her dealings with the shopkeepers. She calls the grocer “Davioli” and the tailor “Quagliamatti,” without honorifics. Here Petry raises the possibility that even an impoverished colored woman can raise herself above the average run of white people.

Among the burdens Abbie imposes on Link is the necessity to uphold The Race, to be superior to white people—“cleaner, smarter, thriftier, more ambitious”—and also polite, punctual, and conservatively dressed so that white people will like him. Abbie refuses to buy watermelons and porgies because whites associate them with colored people. She never fries fish or chicken because the house will smell. Link’s reaction to these admonitions is two-fold. “[I]t made him feel as though he were carrying The Race around with him all the time.” And it made him recognize that Abbie feels superior to most Blacks. When she says she thinks colored people are all stomach and no mind, “He was temped to say, ‘But Miss Abbie, that’s not possible. Aren’t you colored, too?’ and never did.” Abbie’s attitude reflects the feelings of Petry’s mother, who had benefited from the help of powerful white women in Hartford. In a letter to her younger sister, Lane wrote, “is there anything that can beat white?”

Abbie reflects on the differences between her tenant Malcolm Powther, the Treadway’s butler, and her deceased husband, Major Theodore Crunch. The Major has been dead for 18 years when the novel opens but looms over the action. He was based in part on Petry’s paternal grandfather, “Major” Theodore Lane, who moved his family from “Jersey” to Hartford in the 1870s. Abbie wants to attend a white church, but Major Crunch says he can’t rise to a position of authority there. Both the fictional and real Majors became deacons. Major Lane served at Talcott Street (now Faith) Congregational Church. Petry also borrowed from the life of her maternal grandfather, Willis Samuel James. Major Crunch works as a chauffeur for a governor as did Sam James, who received a letter of recommendation from Connecticut Governor Marshall Jewel (in the collection of the Beinecke Library, Yale University). Petry’s grandfathers had overcome, respectively, a hardscrabble farming life and slavery to become successful men, and she embodied their successes in Major Crunch.

The Crunch family adds another dimension. Stand-ins for the Lanes, they are “an ungodly crew.” The Major calls them “swamp n—–s”: Uncle Zeke can levitate; a great-grandfather bites off the ear of an Irishman; the witch doctor Aunt Hal, forbidden to attend a funeral, appears riding atop the hearse and thumbing her nose at the rest of the family who try to kill her. Petry uses the “emotional, primitive” Crunches to show that not all Black people want the trappings of whiteness and that hostility can run both ways.

In the same lawless category is Bill Hod, who rescues young Link after Abbie neglects him after her husband’s death. Hod owns the bar, the local house of prostitution—and the local (white) police chief. He intervenes on Link’s behalf after the Sambo incident. A word from Hod, and the teacher no longer singles out Link and is instead carefully polite to him.

left: Ann Petry with her mother Bertha Lane, 1939, the year after she moved to New York with her husband, George Petry. The couple lived in Harlem; Ann’s experience there became the basis for Petry’s first and best-known novel, The Street. top right: Theodore “Major” Lane, Petry’s paternal grandfather, was the model for The Narrows character Theodore Crunch. He was a deacon of the historic Talcott Street (now Faith) Congregational Church in Hartford. The Hartford Courant, July 10, 1923. bottom right: “George David Petry,” by Elton Fax, 1939, photo: John Clarke Russ. Used with permission. Petry’s husband George was the model for The Narrows’s main character, Link. Courtesy Liz Petry

Petry’s defender was her father, Peter C. Lane. He wrote to The Crisis in about 1920 complaining that a woman refused to teach his daughters and niece. The teacher “told them before the whole class that they could ‘go to Glory to get a lesson.’” She also told them at the beginning of the term that they would not be promoted. Not only were they promoted, they all graduated. Petry’s sister, Helen, went to Pembroke College, and the niece, Helen Chisholm, to Russell Sage College. Petry went on to receive a degree from the Connecticut College of Pharmacy.

Link’s re-education begins with Hod’s story of the 1919 Chicago riots in which white people attacked innocent Blacks. When a mob arrived at Ma Winters’s rooming house, she “stood at the top of the stairs with a loaded shotgun in her hand, not shouting, not talking loud, just saying, conversationally, ‘I’m goin’ to shoot the first white bastard who puts his foot on that bottom step.’ And did. And laughed. And aimed again. ‘Come on,’ she said, ‘some of the rest of you sons of bitches put your white feet on my stairs.’ And they backed out of the door, … left a white man, a dead white man, there in the hall, lying on his back, a bloody mess where his face had been.” Hod and Weak Knees also imprint on Link the beautiful side of blackness, praising the beauty of black birds, the strength of ebony, and the rarity of black jewels.

Petry drew many of the details of Hod’s life from her most outrageously colorful maternal uncle, Willis Howard James, from whom she learned the Ma Winters story. Uncle Bill admitted shooting a white man, spent time on a chain gang in Georgia, and was nearly lynched. He hopped freight trains all over the East Coast and worked the eastern seaboard and midwest as a waiter, a barber, a circus roustabout, and apparently as a smuggler. Someone in The Narrows asks what a “Chinaman’s chance” means. Frances Jackson says it refers to Chinese immigrants who were tied up in burlap and weighted with stones. “I have heard it said that Bill Hod used to bring them in over the Canadian border. Years ago. At a thousand dollars a head. If the border patrol stopped him, challenged the great god Hod, why he dumped the Chinese overboard.” Petry gleaned this bit of information from Uncle Bill. Through him, she makes the point that even those with comparatively little power can maintain control in their own limited spheres.

While Blacks in The Narrows live in isolation from whites, Petry also explores their common ground. Link and Camilo both realize that adults treat children as though they lack feelings and that children can be equally cruel. A teenaged Camilo was teased by her schoolmates because she was fat. Link can still hear the kids telling him the pigeons were saying, “Lookitthecoon.”

These shared experiences do not mean that the white residents of Monmouth are becoming more accepting, but the novel does conclude with two small rays of hope. As the local newspaper is sensationalizing crimes by Black people, an escaped convict startles a woman in her kitchen. He stuffs a gag in her mouth, grabs some food, and runs. The woman tells a reporter, “‘I hollered because I didn’t know he was there in the kitchen… . I’da hollered the same way if he’d a been a big white man showing up so sudden and unexpected… . ’” She insists that he never “bothered” her and instructs the reporter not to say he did.

Abbie Crunch offers greater expectations. When she realizes that Bill Hod is planning to kill Camilo, she heads for the police station to try to stop him. Here is a Black woman reaching out to a white woman she has previously spurned.

Despite its dark message, The Narrows teaches that reactions born of ignorance or fear can be changed. Perhaps Monmouth is not becoming like Georgia. Rather than breeding the expected contempt, familiarity may breed understanding and acceptance. Maybe there is something new under the sun.

Elisabeth Petry is the author of At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry (University Press of Mississippi, 2009) and Can Anything Beat White?: A Black Family’s Letters (University Press of Mississippi, 2005). A longer version of this essay appears in African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

Explore!

“James Pharmacy” Spring 2007

“Women Who Changed the World” Summer 2011

“Searching for My James and Lane Families” Fall 2019

PODCAST: Novelist Ann Petry and Exploring the Family Tree

Liz Petry’s lecture at the Mark Twain House explores her family tree and her family’s connection to the writer Mark Twain.

Read all of our stories about Connecticut’s art and literary history on our TOPICS page

Read all of our stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page