c) Connecticut Explored, Summer, 2023

By Andy King

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

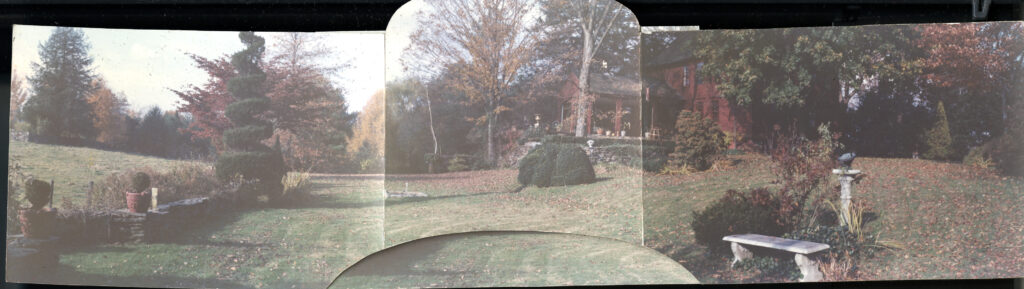

In the mid-20th century many members of what now is known as the LGBTQ+ community chose to live in urban areas such as New York City, New Haven, or Boston. There, as Michael Bronski showed in his book A Queer History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2012), they could find people with similar interests and identities in dense neighborhoods, hiding in crowds for protection during some of the most anti-gay decades in the United States. Away from the bustling blocks of New York’s Greenwich Village or Boston’s South End, rural areas sometimes provided another kind of safety for queer people in the form of seclusion. The Palmer-Warner House in East Haddam, Connecticut, was an island for its inhabitants, preservation architect Frederic Palmer and his partner, Howard Metzger. There, on 50 acres of secluded land, they created a sanctuary where their friends could visit and be themselves. They were out of sight from potentially peering neighbors, and distanced from others in a town where Palmer’s contributions to local historic preservation, including the restoration of the Goodspeed Opera House, afforded him the privilege of privacy in his private life.

Frederic Palmer and his mother, Mary Brennan Palmer, purchased the 1738 home and its land in 1936. The 34-year-old architect saw the possibility of shaping the historic estate to suit his lifestyle. The Colonial Revival movement was a part of the larger historic preservation movement in America. During a time of political upheaval and social and economic changes – the Great Depression, a rise in immigration, and marginalized communities gaining social and economic standing – Some wealthy white Americans sought refuge within the past. Especially in a town as rural as East Haddam, the home could be a perfect getaway from the tumultuous present. Palmer was a conservative-leaning white man with generational wealth who may have felt threatened by the empowerment of marginalized communities. However, through oral histories conducted by Connecticut Landmarks and Palmer’s diaries, scrapbooks, and letters, we know that he had relationships with men, creating a complex intersection of identity.

Frederic Palmer and his mother, Mary Brennan Palmer, purchased the 1738 home and its land in 1936. The 34-year-old architect saw the possibility of shaping the historic estate to suit his lifestyle. The Colonial Revival movement was a part of the larger historic preservation movement in America. During a time of political upheaval and social and economic changes – the Great Depression, a rise in immigration, and marginalized communities gaining social and economic standing – Some wealthy white Americans sought refuge within the past. Especially in a town as rural as East Haddam, the home could be a perfect getaway from the tumultuous present. Palmer was a conservative-leaning white man with generational wealth who may have felt threatened by the empowerment of marginalized communities. However, through oral histories conducted by Connecticut Landmarks and Palmer’s diaries, scrapbooks, and letters, we know that he had relationships with men, creating a complex intersection of identity.

Palmer met Howard Metzger through a mutual friend, Jack Pierce, in March 1945. By June, Metzger had a room at the house, where he often stayed when he was not at sea as a United States Merchant Marine. In their correspondence, Palmer often professed how he missed Metzger. He warned Palmer to not reveal too much about their relationship in their letters, which were inspected by censors. Palmer varied his postmarks to avoid any suspicions that might arise from Metzger’s receiving frequent mail from the same man. According to Allan Bérubé’s book Coming Out Under Fire (North Carolina University Press, 1990), it was dangerous to leave evidence of engaging in gay relations. Bérubé notes that gay men in the service faced discrimination: they risked their safety among peers, could be discharged from service, were regarded as mentally ill or perverted, and were often denied veteran benefits in an effort to dissuade gay people from joining the military.

Panoramic landscape, lower grounds of Palmer Warner House, likely taken by Frederic Palmer. Image-courtesy-of-Connecticut-Landmarks-Palmer-Warner-House-Collection, November 3 1965

At the same time, the military was attractive to gay men and lesbians as a realm in which expectations regarding marriage and traditional family could be less pressing than in civilian life, Bérubé observes. Although a civilian organization, the Merchant Marine’s appeal might have been similar to that of the military.

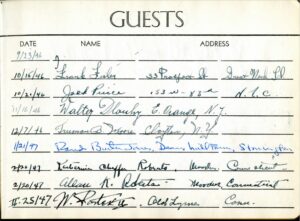

While home in East Haddam, the couple often hosted gatherings for their friends, many of them gay men looking to escape the summer in New York City, as evidenced by Palmer’s diaries, letters, and the house guest book in the Connecticut Landmarks archives. Howard cooked, and Frederic showed off the home they worked so hard on. No photographs of these gatherings exist, though, perhaps because the guests did not feel safe having their pictures taken in that milieu.

Indeed, cultural and political events during Palmer’s lifetime encouraged gay people to protect themselves. Palmer attended Harvard during the Lavender Scares, when a secret court was set up to identify and expel gay students, and he died two years after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, a weekend of protests that launched the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement. Palmer lived his entire life knowing his safety as a gay man was never assured.

Palmer left his home to Connecticut Landmarks intending to have the site interpreted as a colonial Connecticut history and preservation story. His bequest allowed Metzger to continue living there until his own death in 2005. At the same time, they had carefully curated their home to represent 20th-century men living in an 18th-century home. Today the site’s interpretation honors both parts of Palmer’s identity, in keeping with the “best practices” described in recent books like Susan Ferentinos’s Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites (Roman & Littlefield, 2015).

Typically, queer people left rural areas because, in a fishbowl, they felt unsafe. But Palmer’s privilege allowed him to make his East Haddam home an exception. The community that Palmer fostered found in seclusion the safety to gather, love, and thrive on their rural island of privacy.

Andy King is working on their master’s degree in public history at Central Connecticut State University. They are the membership and programs coordinator at Essex Historical Society and the communications manager for the Connecticut League of History Organizations.

Explore!

For more information about Palmer and Metzger’s personal relationship read Erin Farley’s “SiteLines: A Love Story at the Palmer-Warner House,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2019.

For more information about Palmer and Metzger’s personal relationship read Erin Farley’s “SiteLines: A Love Story at the Palmer-Warner House,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2019.

To learn more about the site and events visit ctlandmarks.org/properties/palmer-warner-house or email palmer.warner@ctlandmarks.org