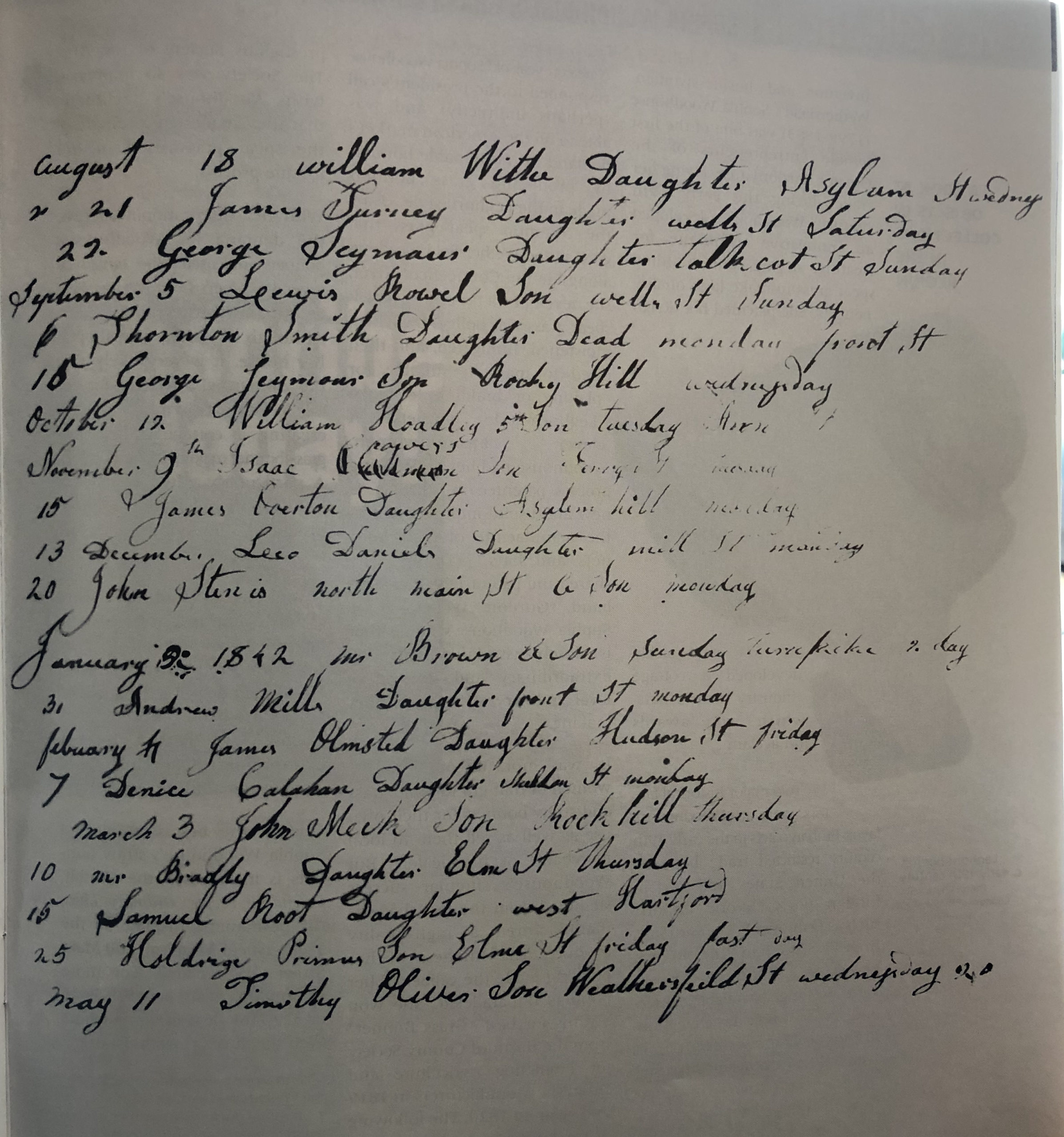

A page from midwife Jennet Catlin Boardman’s account book, August 18 – May 11, 1842. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

By Sharon Y. Steinberg

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Racing across muddy and dark streets, day and night, holiday or not, Hartford mid-wife Jennet Catlin Boardman (1765 – 1849) braved the elements and worked against time and the specter of death to reach women in labor. From 1815 through 1849 Boardman was one of Hartford’s busiest healers and midwives, delivering almost 1,200 babies in 34 years and ministering to other sick children throughout her life. She delivered her last child when she was 84 years old in the year of her death. Beginning at age 50, after having nine children of her own, she traveled from her house on the corner of Broad Street and New Britain Avenue to assist women of all classes, neighborhoods, and races in Hartford, Bloomfield, Windsor, Rocky Hill, and Middletown. Boardman, in her own words, braved “great & driving snow,” and sacrificed many a Christmas and Thanksgiving with her family to minister to women in need. Most babies survived, but not all. She lost 77 children during those 34 years.

Her midwife records survive in readable condition in the manuscript archive of the Connecticut Historical Society. Writing with a quill pen, she dispassionately recorded only the father’s name, the sex of the child, the date of delivery, the location of the home, often the ethnicity or race of the family—“irish” or “coulard,” for example—and whether the child lived or died. Neither the babies’ nor their mothers’ names were recorded, except for those of single or widowed women. She often also noted return visits to the family, months and years later, to provide medical care for the child. Boardman charged about $2 per birth and earned approximately $2,226 in her midwifery career.

From May 16 through September 6, 1827, she delivered 20 babies, including a son for one Jeremiah Wadsworth who died. Tragedy also struck the Wright family who lived on Pearl Street whose mother gave birth to “two daughters live one 8 lbs, dead 6 lb 6 oz.” A “coulard” child was born to the Freeman family who lived in “hotel alley.”

From August 18, 1841 through May 11, 1842 (illustrated), Boardman delivered an average of two babies a month. On September 6, 1841, Boardman traveled to Front Street in Hartford, but Thornton Smith’s daughter died. During these months, she also traveled to Rocky Hill and the West Division of Hartford (now West Hartford), and on “fast day,” February 25, 1942, she delivered Holdrige Primus’s son Nelson. The Primus family was an important African American family in Hartford. Nelson Primus became a renowned portrait painter and his sister, Rebecca Primus, became a teacher to formerly enslaved people in the South after the Civil War.

Tracing Boardman’s steps through Hartford was a challenge because street names have changed, and some  have disappeared entirely. The most puzzling description was the term “neck,” which was the old name for a small section of Hartford that ran from North Front Street to the North Meadows.

have disappeared entirely. The most puzzling description was the term “neck,” which was the old name for a small section of Hartford that ran from North Front Street to the North Meadows.

Jennet Boardman is the only person listed in the 1828 Geers Hartford City Directory as “midwife,” a recognized occupation during a time when women were discouraged from working outside of the home and before hospitals and formalized medical training were available. She broke out of the private sphere of 19th-century female domesticity into the very public world of Connecticut’s towns and back into the private turmoil and anxiety of mothers-in-waiting. Her heroic and skillful efforts are quietly recorded in these journals and tell early Hartford’s dramatic and intimate story of pain, sacrifice, joy, and the power of womanly nurturing.

Sharon Steinberg is an historical researcher and reference librarian at the Connecticut Historical Society.