(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

If you believe that every object can tell a story, then a scrimshaw coconut shell in the Connecticut Historical Society collection tells a great one. Scrimshaw was an “occupational art” practice by American whalemen and other mariners from the late 18th to early 20th centuries, primarily to pass idle hours. Examples include decorative pieces like engraved whale teeth and utilitarian items as diverse as pie crimpers, canes, corset busks, and winding swifts. Whaling by-products, primarily teeth, skeletal “panbone,” and baleen often were combined with materials such as metals, tropical woods, wax, mother-of pearl, and, yes, even coconut shells.

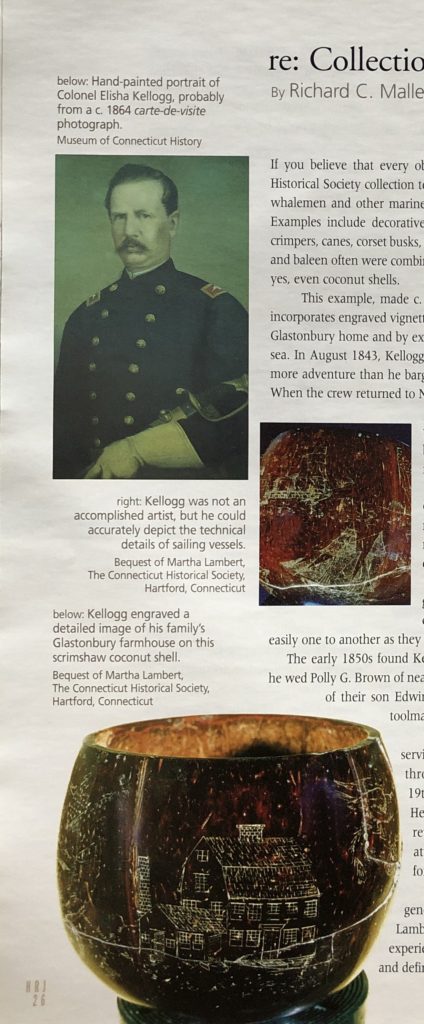

This example, made c. 1851 and attributed to Elisha S. Kellogg (1824-1864), is unusual in that it incorporates engraved vignettes providing glimpse into Kellogg’s early life. One scene faithfully depicts his Glastonbury home and by extension the farm life he, like many young men, sought to escape by going to sea. In August 1843, Kellogg signed aboard the New London whaling bark, Halcyon. He may have found more adventure than he bargained for, as one year later the vessel wrecked at Geographe Bay, Australia. When the crew returned to New London the following May they had little to show for their labors.

Another skillfully engraved vignette on the coconut shell illustrates two sailing vessels typical of the period. Though it cannot be confirmed, a biographical sketch suggests that Kellogg again went to sea for a time on a merchant – not whaling – vessel, perhaps similar to the one depicted here.

Kellogg apparently caught “Gold Fever” in 1849, sailing from New York to California with other adventurers on the ship South Carolina. However, like most of these fortune-seekers, Kellogg failed to strike gold. The shell boasts a mining camp scene, complete with tents, tools, and even a screener, likely dating git to his return voyage.

Completing Kellogg’s visual tour de force are groupings of patriotic, geomatic, and mourning imagery typical of scrimshaw. Despite the seeming crowding on the four-inch-diameter shell, the different themes transition easily one to another as they broadly trace Kellogg’s life through mid-century.

The early 1850s found Kellogg learning tool-making, possibly near Sheffield, Massachusetts. In 1853 he wed Polly G. Brown of nearby Winsted, Connecticut, where the couple lived until shortly after the birth of their son Edwin in 1856. The family then relocated to Derby, where Elisha worked as a toolmaker and mechanic.

The outbreak of the Civil War found Kellogg among the state’s early recruits, serving with the 1st Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery in 1861. He rose through the ranks and was ultimately promoted to colonel of the 19th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment (later designated the 2nd. C.V. Heavy Artillery). During the campaign at Cold Harbor, Virginia, this unit reverted to infantry service. Elisha Kellogg died leading his men in repeated attacks against Confederate defenses on June 1, 1864. His body was returned for burial in Winsted.

Kellogg’s scrimshaw coconut shell descended through several generations, coming to CHS as a gift from the family of grand-nephew John Lambert. Today it offers mute yet moving testimony to a young man whose experiences included episodes of high adventure that in some ways both reflected and defined his character.

Richard C. Malley was director of collections access at The Connecticut Historical Society. A maritime historian by background, he has written two books on the art of scrimshaw, which he says “provides a glimpse into the shipboard lives of sailors in an isolating and psychologically demanding work environment.”

Explore!

Read more stories about Maritime Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Read more about Connecticans in the Civil War on our TOPICS page.

Read another story about a Connectican in the Gold Rush HERE.