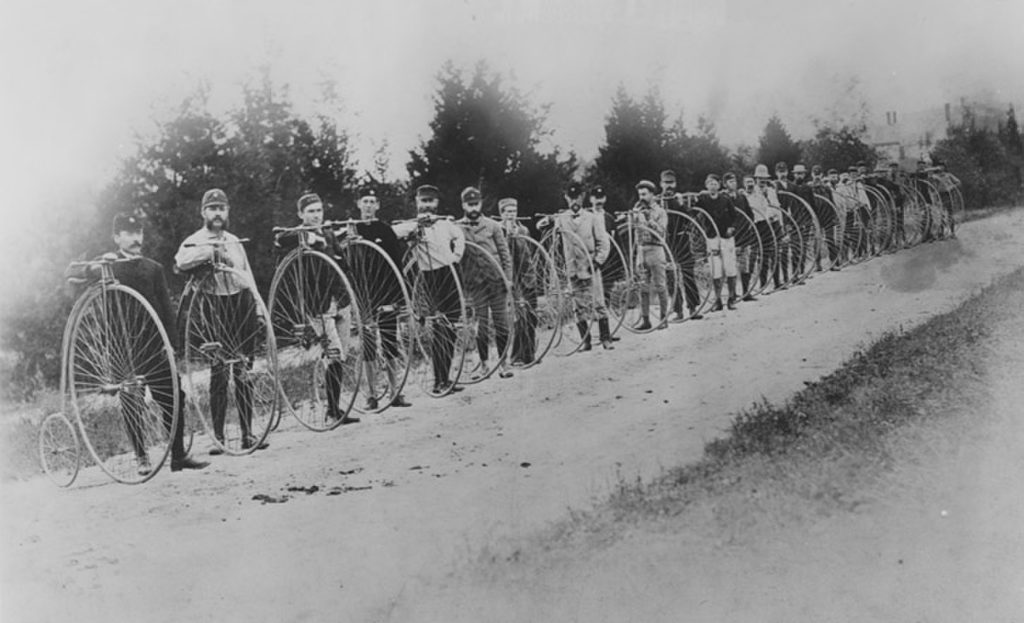

Col. Albert A. Pope, president of Pope Manufacturing Co., second from left, on a bicycle tour, Readville, Massachusetts, 1879. National Museum of American History

By Walter W. Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

One of the characteristics that defined the Victorian era was its many advances in invention and technology. One of the most significant of those advances was brought to the United States and produced in Hartford by Colonel Albert Augustus Pope. The Ordinary bicycle, an extraordinary two-wheeled human transportation vehicle we now commonly think of as the high-wheeled bicycle, ushered in a short, but important, revolution in transportation. The Ordinary (as it later came to be called to differentiate it from newer “safety” bicycles) not only produced the bicycle industry, it generated public demand for better streets and highways, new rules of the road, and vehicular tourism. It also led to the nation’s first transportation lobbies and paved the way for the automobile era that followed, in which Pope played another pioneering role.

Pope, an entrepreneurial Civil War veteran and owner of a successful shoe supply firm in Boston, first encountered the high-wheeled machine, then called the velocipede, on a visit to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. According to Stephen B. Goddard, in Colonel Albert Pope and his American Dream Machines (McFarland, 2000), the ungainly British import fascinated Pope, who returned to the exposition several times to see it. While many visitors viewed the velocipede as a potential faddish pastime, Pope saw it as the machine that could liberate human travel from the tracks and timetables of the railroad industry.

Pope visited England to learn how the velocipede was made, hired an English friend to help him design an improved version, secured the necessary American patent rights, and arranged with Hartford’s Weed Sewing Machine Company in the spring of 1878 to produce 50 of his new Columbia Ordinaries. These were the first production bicycles made in America, according to Goddard, and they met with immediate success.

Within two years, production increased to 12,000 Ordinaries, with a backlog of 2,500 orders. A year after that, Pope had gained control of the entire Weed company’s production, and by the end of the decade, Americans purchased more than 200,000 bicycles a year from Pope and other manufacturers, according to the Smithsonian (si.edu/spotlight/si-bikes/si-bikes-ordinary.)

Pope worked to increase the market for his bicycles across several fronts. In addition to active print advertising and public relations campaigns, Pope established riding schools, where, according to Charles Pratt in the 1884 pamphlet What & Why. Some Common Questions Answered (Rockwell and Churchill), purchasers could learn to ride the high wheelers in “from twenty minutes to six half hour lessons.” Pope organized bicycle clubs—40 of them in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania alone by 1880—whose members sponsored bicycle parades, long-distance tours, and speed and endurance competitions. Members became vocal advocates both for bicycling and better roads.

Pope funded legal battles against town ordinances seeking to ban or restrict the use of the new vehicles, and in what may have been the promotion with the most far-reaching consequences, he became an outspoken champion of improved streets and highways. In May 1880 Pope announced the formation of the National League of American Wheelmen, a group that, according to Goddard, was dedicated to making roads, not rails, “the primary arteries of American recreation and commerce.” Its periodical publication Good Roads led the charge that resulted in most states and the federal governments creating road-building programs by the 1890s.

As the fame of Pope’s bicycles grew, they also changed. The always precarious Ordinary bicycles were gradually replaced by the safety bicycle (with wheels of the same size) we associate with biking today. [See “The Vehicle of Healthful Happiness,” Spring 2003.] And as roads improved, bicycles gave way to another innovation, the automobile. Here, Pope again proved an innovator. In 1897 Pope’s Columbia Motor Carriage Company in Hartford introduced what it believed would be the transportation mode of the future, the country’s first battery-powered electric automobile. [See “The Horseless Era Arrives,” Spring 2005.]

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut state historian. Listen to his podcasts at Gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com and visit TodayinCTHistory.com.

GO TO THE NEXT STORY

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!