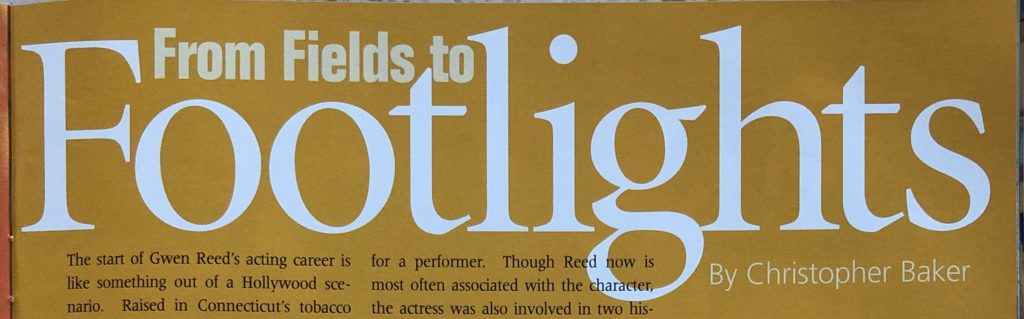

On the reverse is written: “To ‘Aunt Jemima’, ‘Miss Gwen Reed’, in appreciation of an excellent TV. show. Most sincerely, Mildred Carlson, WBL-Boston, Mass.” February 1951. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library.

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. May/Jun/Jul 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

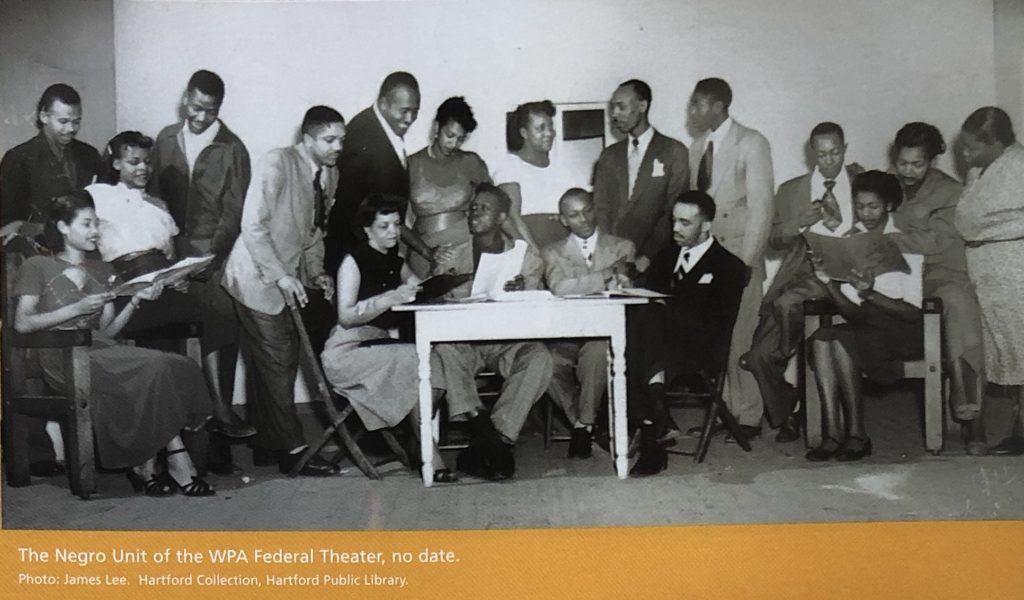

The start of Gwen Reed’s acting career is like something out of a Hollywood scenario. Raised in Connecticut’s tobacco fields, she worked as a secretary with a small theatre troupe when she stepped out from behind the scenes to take a bit part. Noticed by critics and audiences, she continued acting for over three decades. Though fame and fortune were not part of Reed’s story, she was a familiar face on Hartford area stages and afternoon television, playing many roles, from the imposing Maria in Porgy to the mysterious Assunta in The Rose Tattoo to the wise and loving Bernice in Member of the Wedding.

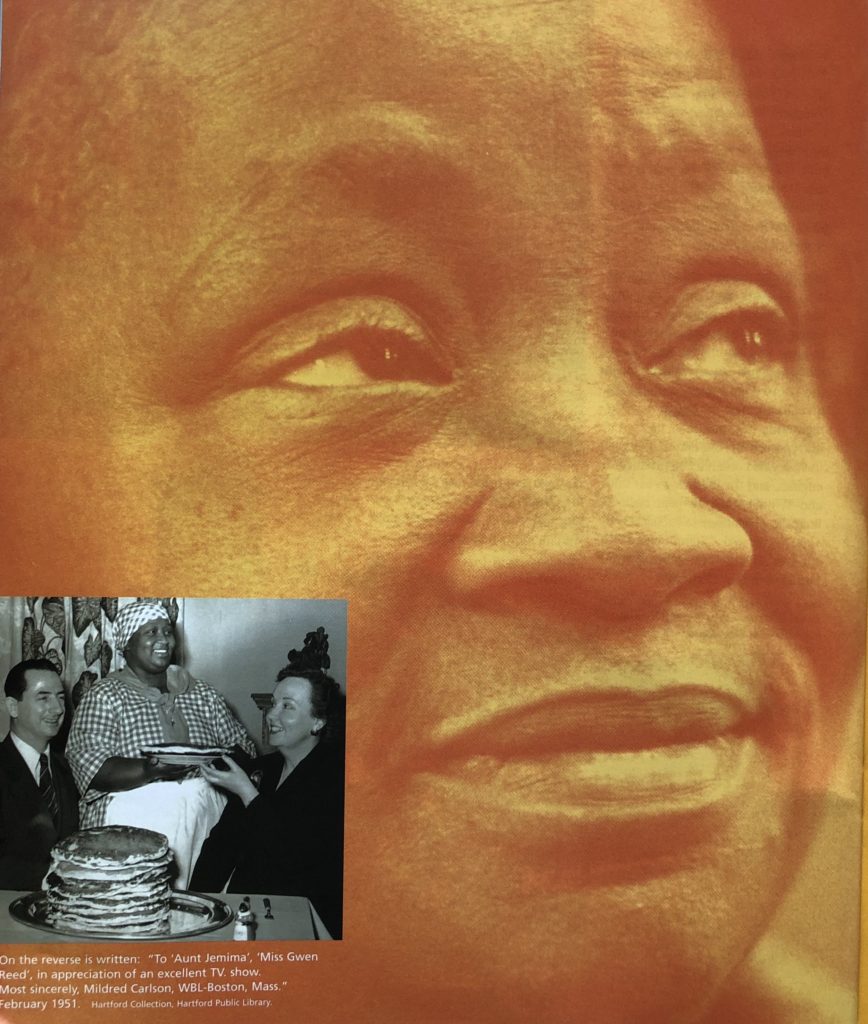

None of these roles had as long a run, however, nor brought as much attention, as her 17-year stint as an employee of the Quaker Oats Company. At grocery store openings, Jaycee breakfasts, and school assemblies, dressed in the familiar apron and red-and-white bandana, Reed was one of many women employed by the company to play Aunt Jemima, serving up freshly cooked pancakes and sometimes a song or two. Like department store Santas or theme-park characters, Quaker Oats maintained the illusion that Aunt Jemima herself had stopped by for the festivities, not a performer in costume. From 1946 to 1964, Reed worked more or less anonymously as the famous pancake-box cook. “Honey, it doesn’t make any difference who I am,” Reed told the Portland (Maine) Evening Press when asked to reveal her identity, “I’m happy to be here.”

Actress Gwen Reed flipping pancakes as “Aunt Jemima” for the Quaker Oats Company, May 20, 1948. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

Portraying Aunt Jemima provided steady employment for Reed, a coveted situation for a performer. Though Reed is now most often associated with the character, the actress was also involved in two historical theatrical ventures in Hartford – the ambitious Depression-era Federal Theater Project, with which Reed made her debut, and the regional theatre movement of the 1960s, experienced in Hartford as a brash new theater called the Hartford Stage Company, where Reed performed in its early seasons.

Her theatrical career and other aspects of her life are recorded in newspaper clippings, theatre programs, scrapbooks and other personal documents of the actress now part of the Hartford Collection of the Hartford Public Library. These papers give an incomplete glimpse of a fascinating woman who came to the city as a migrant farm worker and stayed to become a beloved stage and television personality and teacher.

Gwen Reed was born Gwendolyn Clarke in 1912 in Harlem to Georgianna and George Nathanial Clarke. After Gwendolyn’s birth, Georgianna fled both husband and Harlem, taking her daughter with her. The two drifted for many years as Georgianna worked as an itinerant field hand in Maine, Florida, California, and elsewhere.

The tobacco fields of Connecticut lured Georgianna and Gwendolyn to Hartford again and again. As a young child, Gwen earned money in the sheds picking up the fallen tobacco leaves for 10 cents an hour. The two permanently settled in Hartford in 1921, where Gwen graduated from Arsenal Elementary and Hartford Public High School.

Her greatest education may have come, however, at her mother’s knee, where she acquired a love of literature and storytelling. In the migrant camps, after writing or reading letters for illiterate workers, Georgianna would read Tennyson and Shakespeare. “She taught me the 23rd Psalm,” Gwen once told a reporter, “while she knelt weeding cucumbers and radishes.” After high school, Gwen continued to work in the tobacco fields. Though she attended Hartford Federal College hoping to become a lawyer, illness forced her to drop out. In 1935 she married John T. Reed. The marriage license lists his occupation as “truck driver,” hers as “tobacco worker.” After four years the couple separated and in 1948 divorced.

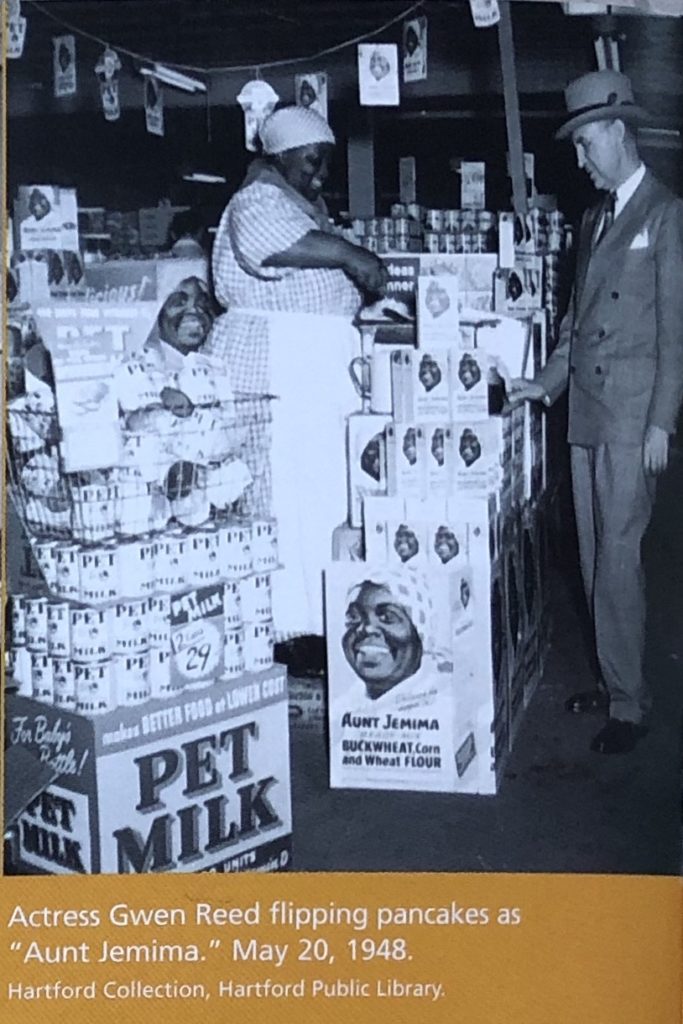

Reed eventually took a job as a secretary in a small Black theatre group, the Charles Gilpin Players. Named after the great African-American actor who created the leading role in Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, it was formed (as were many other Gilpin Players around the country) shortly after President Harding honored the actor at the White House in 1921. In the fall of 1936, in the midst of the Depression, the financially strapped Gilpin Players turned to the federal government for financial and artistic help. Assistance was provided in the form of the Federal Theater Project.

The Negro Unit of the WPA Federal Theater, no date. Photo: James Lee. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

The Federal Arts Program was inaugurated in 1935 as a program of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to put writers, painters, musicians, and theatre practitioners to work. Though the idea provoked controversy WPA head Henry Hopkins answered his critics with the line, “Hell, they’ve got to eat just like other people.” The Federal Theater Project was the theatrical arm of the program. It funded companies throughout the nation and sent professionals to groups that needed them. Project Director Mollie Flanagan insisted on the highest artistic standards, though WPA rules often hindered planning and created tension between amateurs and professionals. Within the WPA, the Federal Theater Project was seen as an unwelcome stepchild, often ignored by the very officials who were administering the program. Nevertheless, the Federal Theater Project forged ahead, with notable successes by Orson Welles and John Houseman. The Connecticut arm of the Project began in New Haven with a production of Men Must Fight. It then moved to Hartford, where it provided work for a young Ed Begley and premiered the stage adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here simultaneously with troupes in 20 other cities.

The Charles Gilpin Players applied to the project for a professional director and in 1936 was organized as one of the Federal Theater Project’s Negro Units. These specialized companies for African American performers had less support than the white troupes and were usually run by white directors. They were suspected, both in and out of the WPA, of being social programs rather than artistic initiatives. But the Negro Units remain an important chapter in American theatre history, having nurtured the careers of important Black artists and funded notable productions such as Swing Mikado, Turpentine, Big White Fog, and the “voodoo” Macbeth directed by Orson Welles. Negro Units were also formed in New York, Chicago, Seattle, Philadelphia, Boston, San Francisco, Atlanta, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Durham, Raleigh, New Orleans, Detroit, Cleveland, Portland, Los Angeles, Greensboro, and Birmingham.

Gwen Reed in The Field God by the Negro Unit of the WPA Federal Theater at the Avery Memorial (Wadsworth Atheneum). February 1938. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

In Hartford the Negro Unit was under the direction of Michael Adrian (born Victor Ecchevaria in Puerto Rico), who also worked with Hartford’s white unit as a director and designer. His 1936 production of The Sabine Women at the Palace Theater on Main Street excited both public and critics. “There is no limit to what might be accomplished by Hartford’s Negro Unit,” the Hartford Times wrote, “which is now under the guiding genius of Michael Adrian, as remarkable director as ever put on a show in Connecticut.”

Aside from Adrian and some technicians, the Charles Gilpin Players only had a staff of four, including Reed, relying on some 100 volunteers. The success of The Sabine Women led the WPA to establish the group as a fully paid operation. For all intents and purposes The Gilpin Players were no more, having been completely absorbed into Connecticut’s Negro Unit. Most of the subsequent productions were staged in the Wadsworth Atheneum’s theater in the Avery Memorial, though some toured to other locations.

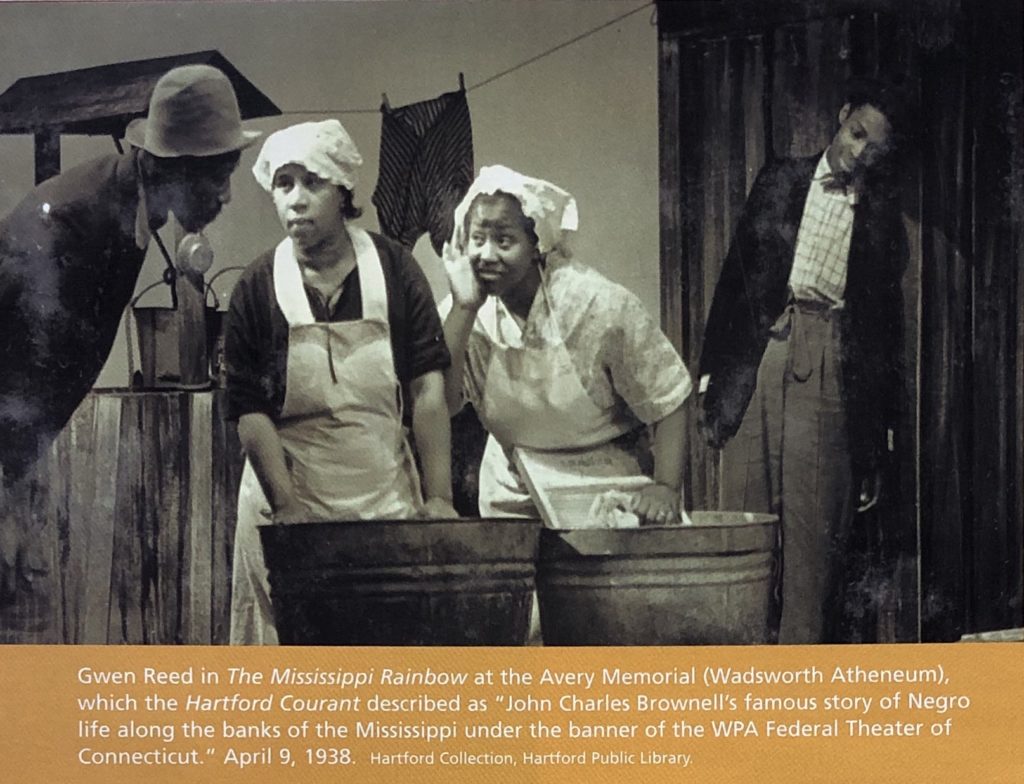

On June 18, 1937, the Negro Unit presented Trilogy in Black, commissioned by the troupe from playwright Ward Courtney. Reed played the small role of “1st Lady.” Though she had often made up her own plays as a young girl, and had performed in some church presentations, this was truly her debut as an actress. Reed then appeared in the chorus of The Emperor Jones and in Jericho, for which the press singled her out. Subsequent roles in The World We Live In, Mississippi Rainbow, and In the Valley established Reed as a Federal Theater Project favorite. As May in Paul Green’s The Field God in February 1938, the actress was lauded by one reviewer as “by far the best player.” The next month she played Marie in Dorothy and Dubose Heyward’s Porgy, the Hartford Times calling her “voluble and convincing…with a heart as big as all outdoors.”

Gwen Reed in The Mississippi Rainbow at the Avery Memorial (Wadsworth Atheneum), which the Hartford Courant described as “John Charles Browne’s famous story of Negro life along the banks of the Mississippi under the banner of the WPA Federal Theater of Connecticut.” April 9, 1938. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library.

In October 1938, the Negro Unit and White Unit in Hartford combined forces to present William DuBois’ Haiti, in which Reed played a small role. She was part of the ensemble when they merged again in January 1939 to present the agit-prop play about the housing crisis, One Third of A Nation, at the Avery and Bushnell memorials. In preparation for that massive project, intensive classes in speech and movement were held for members of both companies. Later that year the entire Federal Theater Project ended, torpedoed by congressional opponents of the New Deal who painted the enterprise as a platform for Communist propagandists. The Hartford Negro Unit disbanded. Reed went back to the tobacco fields to earn a living. Her acting career, however, was not over.

In 1946 Reed began impersonating Aunt Jemima. Covering territory that largely consisted of New England, Reed appeared at fairs, parades, picnics, hotels, and department stores and went into schools with a musical program. She was not, of course, the only one to do so. Quaker Oats employed performers across the country to portray the fictional cook. From 1893, when Nancy Green first impersonated Aunt Jemima at the World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago, through the 1960s, actresses flipped pancakes while repeating the company’s invented legend about being the Higgim Plantation’s culinary genius.

In the newspaper clipping and announcements of her appearances, Reed’s name is never mentioned. A Manchester (Connecticut) Herald photo caption of 1955 is typical: “Aunt Jemima arrived in town today, brilliant in her red and white check outfit, and Mayor Herald A. Turkington, together with Elk dignitaries, welcomed her.” When she went into the schools with her music program, however, the teachers knew the actress’s real name, as letters of thanks and praise attest. As Reed became a veteran spokesperson Quaker Oats accommodated her family obligations; when Reed’s mother grew increasingly ill, her territory was adjusted so she would never be far from home. In her 16th year, she was “inducted” into the company’s Aunt Jemima Hall of Fame.

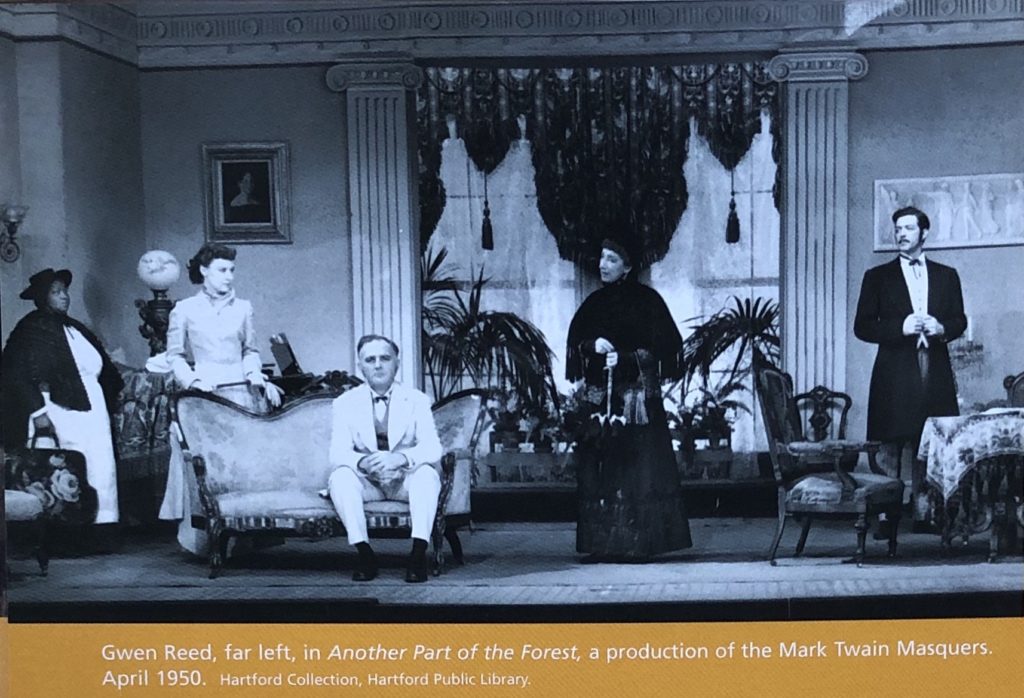

Gwen Reed, far left, in Another Part of the Forest, a production of the Mark Twain Masquers. April 1950. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

Playing Aunt Jemima did not keep Reed from playing other roles. An active participant in community theaters, she appeared with the Mark Twain Masquers, Cue and Curtain, Glastonbury Players, Center Playhouse, Image Playhouse, Triangle Players and The Oval, winning rave reviews for her performances in Stage Door, Rain, Finian’s Rainbow, Purlie Victorious, Raisin in the Sun, The Little Foxes, Member of the Wedding, and Showboat. She was also a director of the Hartford Community Players in the 1940s and 50s, a Black troupe dedicated to promoting theatre in the African American community.

Reed’s work in those theaters brough her attention, but no pay. One theatrical venture with which Reed was involved, however, not only paid, but grew to become a major cultural institution.

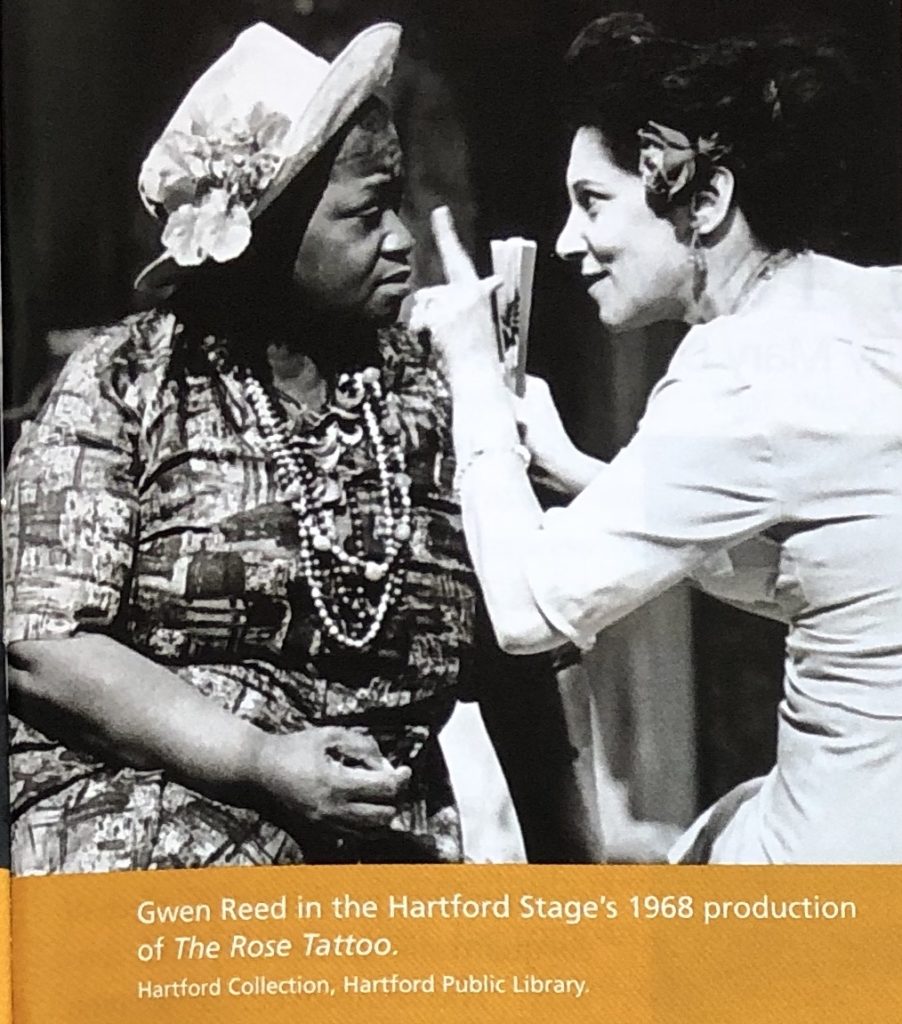

On April 1, 1964, in a converted grocery store warehouse on Kinsley Street, the Hartford Stage Company opened its doors with a production of Othello. Its mission was to bring serious professional theater to the area, in contrast to the educational, community, or touring commercial shows that were available at the time. Though founder Jacques Cartier had his attention focused on Hartford, the company’s creation was part of a movement across the country. In Minneapolis, New Haven, Louisville, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, theaters sprang up, dedicated to classical works, innovative new plays, and high standards of professionalism. Hartford Stage Company’s early years proved to be a fertile ground for major talents of the next four decades. Reed played Sookie in Cartier’s production of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1965 and was an understudy for Max Frisch’s The Firebugs in 1968. That same year she appeared in Williams’ The Rose Tattoo as the medicine woman, Assunta. In 1970, she joined the theater’s board of directors for a four-year term.

By the time of The Rose Tattoo, Reed had been active in educational and community work for many years. She worked in schools, with the Jobs Corps and with early childhood initiatives. She developed the preschool project Story Time for Tots and taught in the nascent Head Start and Reading is Fundamental programs. Reed’s educational and theatrical pursuits combined in her 1960s television show “Story Time with Gwen Reed” that had Hartford area children tuning in every Friday afternoon to Channel 3.

Gwen Reed in the Hartford Stage’s 1968 production of The Rose Tattoo. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

Reed’s career was not a lucrative one. When she died in 1974, she left behind few material possessions in the Bellevue Housing Project where she lived. But those who knew her knew her life was rich, as the many awards, citations, and letters in her collection attest. When Reed could not appear one Friday for her Story Time program, children wrote in telling her how much they missed her. A local group organized a tribute to her in 1968 to honor her theatrical, educational, and community work. Surprisingly, for a woman who portrayed a renowned pancake-maker for so many years, she claimed she could not “cook a morsel” and that she relied on her many friends for her meals. After her death a few friends acquired her personal papers for the Hartford Public Library, enabling later generations to learn from her work. On May 2, 1981 Hartford Mayor George A. Athanson dedicated the Gwen Reed Room at the Ropkins branch of the Hartford Public Library, to be used, appropriately, for storytelling.

Many remember Reed from her Friday afternoon television show, some as a teacher, others as Aunt Jemima. But the whole of Reed’s life and career is worth remembering, for it reveals the life of an artist, struggling to work for one’s art and to work to pay one’s bills at a time when neither was easy for an African American woman. From tobacco fields to television, from Hartford Stage to Head Start, from WPA projects to publicity appearances for a national consumer products company, Reed’s life and career intersected important historical moments and social movements. We celebrate her today as a pioneer who stepped out of the tobacco fields and onto center stage to pursue her dreams.

Christopher Baker was the Associate Artistic Director of Hartford Stage.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art history, including actress Marietta Canty, on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories about the African American experience on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories from the May/Jun/Jul 2004 issue.