(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Public housing projects in many ways represent a visionary social experiment. The burgeoning defense industry, prompted by the Second World War, exacerbated housing shortages for workers in Connecticut and nationwide. This need for housing put additional pressures on already overcrowded tenements in urban neighborhoods. Low density housing, surrounded by lawns, gardens and trees, was seen by planners as a way to improve living conditions for poor and working-class families. Although the construction of housing projects solved the immediate need for affordable housing during wartime and the booming postwar years, poor design, shoddy construction, changes in federal housing policy, weak local management, and regional economic decline took their toll. By the 1980s these projects were considered failures; they were plagued with drugs and crime and viewed as a blight on the environment. During the 1990s many were demolished. These photographs, from the files of the Hartford and Middletown housing authorities, offer a look at the history of public housing in the two cities and a preview of the role public housing may play in the future.

Public housing construction in the United States began with the passage of the Public Housing Act of 1937. Soon local housing authorities, thought to be more responsive to local needs, were created. From the start, the federal government regulated the kind of housing that could be built, drafted rules for selecting tenants, and devised formulas for setting rental fees based on family income. In 1965 local housing authorities came under the jurisdiction of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

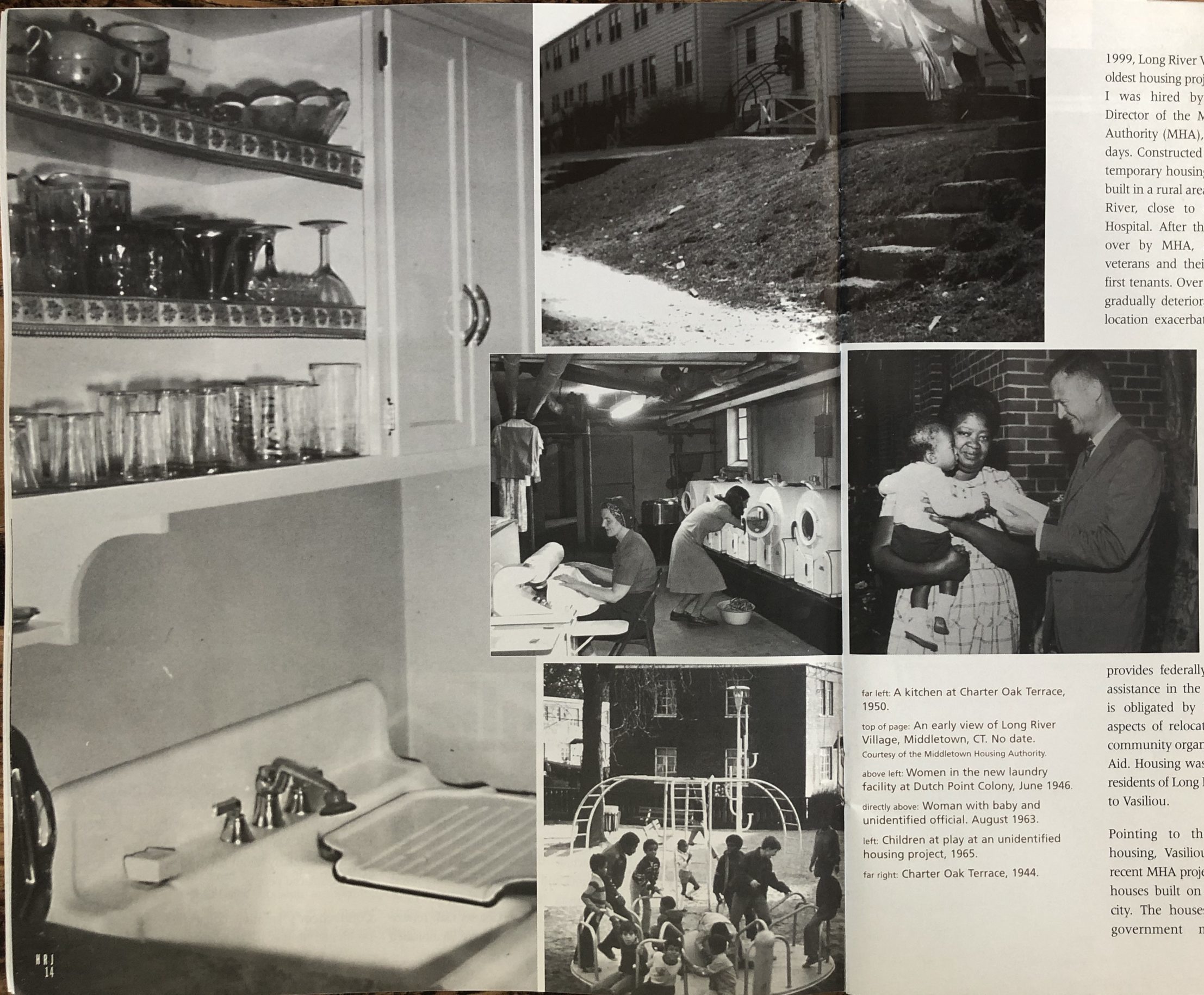

In 1940, the Hartford Housing Authority broke ground for Connecticut’s first public housing project, a 146-unit complex called Nelton Court. In 1941, the 222-unit Dutch Point Colony, the 500-unit Bellevue Square and the 1,000-unit Charter Oak Terrace, designed as temporary housing for defense workers, were built. Rice Heights was begun soon after, originally to house war veterans. While some of these housing developments were built in urban areas, Charter Oak Terrace and Rice Heights were built on farmland near the south branch of the Park River. Most of the projects were of a standard design, usually brick or wood row housing and featured playgrounds, a community center, an auditorium, a health clinic, and meeting rooms.

In the early years, African Americans were actively kept out of public housing. As David Radcliffe, author of Charter Oak Terrace: Life, Death and Rebirth of a Public Housing Project noted in an October 2002 interview, “Hartford’s understood policy of ‘controlled integration’ was common in many public housing authorities in the 1950s and 1960s. This approach forced many black families, living in dreadful slum conditions, to wait until a unit reserved for minorities became available, even if other ‘white’ units sat vacant. Underneath this approach was certainly some discrimination, if not downright racism on the part of many developers and bankers who sought to maintain segregated housing and schools.”

Augmenting the gradual shift in public housing occupancy from whites to African Americans were Hispanics, who began moving into Hartford in the 1960s. They came originally as farm laborers to work in the tobacco fields. In need of affordable housing, they soon made up a large percentage of the housing project population.

Currently housing authorities across the country are facing the dilemma of what to do with aging housing projects. Recent attempted remedies include the demolition of existing units and a move toward still lower density housing. Starting in 1996, housing units at Charter Oak Terrace and Rice Heights were demolished and a smaller number of duplex and single-family homes built on the site. Not surprisingly, these moves proved controversial. Many questions were raised, particularly about the futures of the displaced people.

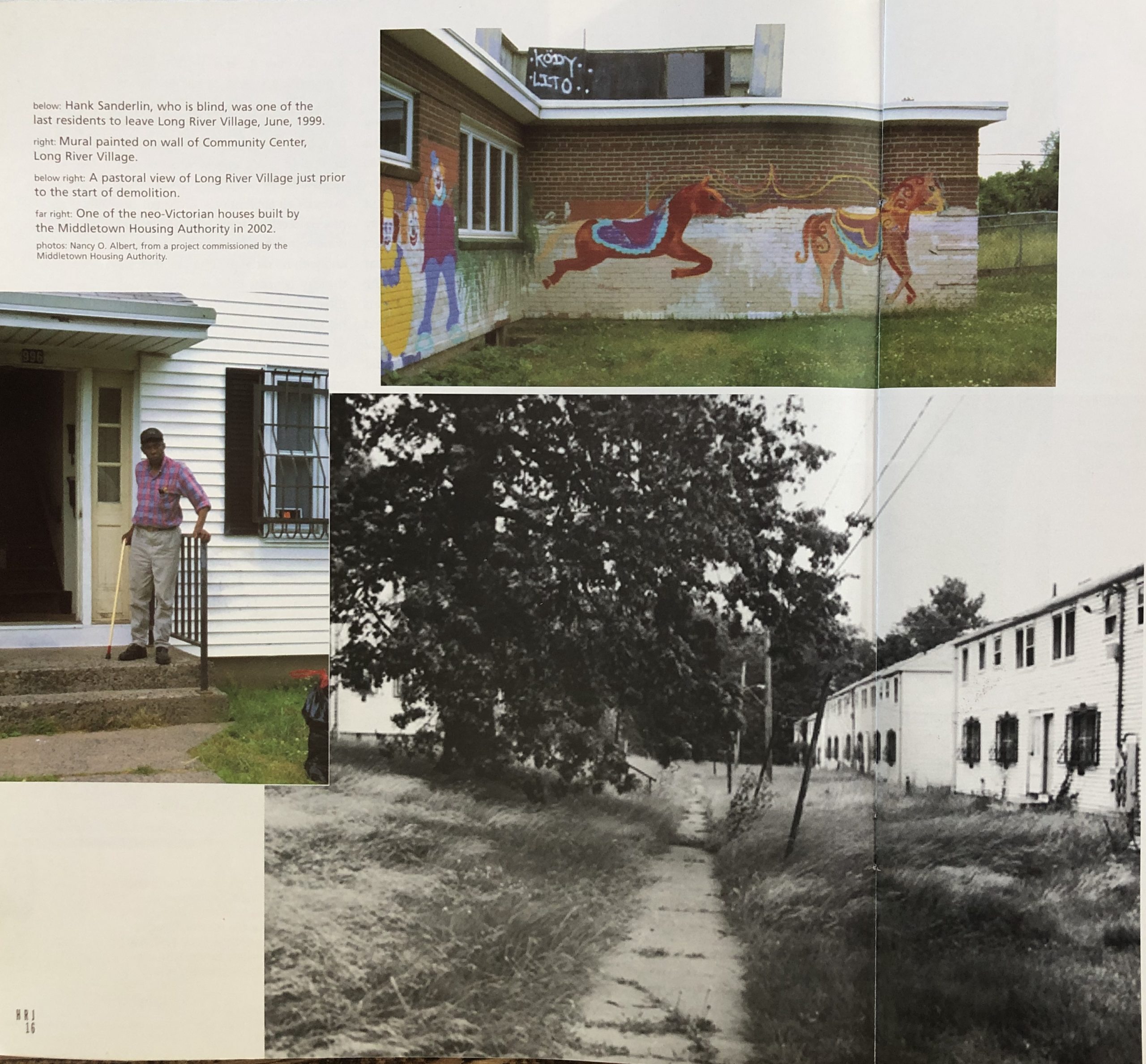

The demolition of Long River Village, summer 1999. Many former residents came by to watch and pick up mementos of their former home. photo: Nancy O. Albert from a project commissioned by the Middletown Housing Authority

Connecticut’s smaller cities face problems similar to Hartford’s. In 1999, Long River Village, Middletown’s oldest housing project, was demolished. I was hired by William Vasiliou, Director of the Middletown Housing Authority (MHA), to document its last days. Constructed during the 1940s as temporary housing for workers, it was built in a rural area on the Connecticut River, close to Connecticut Valley Hospital. After the war it was taken over by MHA, and returning war veterans and their families were the first tenants. Over the years conditions gradually deteriorated and its isolated location exacerbated the problems of drug dealing and other crime.

In October 2002, I interviewed Vasiliou. We discussed what happens to the tenants of Middletown housing projects about to be razed and the future role of housing authorities. When units are demolished MHA tries to move displaced tenants into Section 8, a program it administers that provides federally subsidized housing assistance in the private sector. MHA is obligated by law to assist in all aspects of relocation and works with community organizations such as Legal Aid. Housing was found for all former residents of Long River Village according to Vasiliou.

Unless otherwise noted, all images from the Hartford Housing Authority, Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library.

Pointing to the future of public housing, Vasiliou discussed the most recent MHA project, three neo-Victorian houses built on land donated by the city. The houses were built without government money, which has become limited, and were sold on a preference system at below market value. Existing housing authority residents were given first priority and fifty people applied. Each applicant needed to meet certain income and credit history criteria; a local bank oversaw all applications. Although the process received some criticism, it was done without violation of housing laws and with no racial preferences. He feels the city benefits from the addition of three affordable housing units and it is his philosophy that MHA should play an entrepreneurial role in the community. In this vein, he is currently planning a small townhouse unit specially designed for the hearing impaired.

Vasiliou says that current thinking favors a move away from housing projects. Future units will be smaller, fifty to sixty units at most. Some units will be demolished in remaining projects, lowering concentration and improving design. Projects like Long River Village, built as temporary war housing, lived their useful life. They will never be built again.

A neo-Victorian house built by the Middletown Housing Authority in 2002. photo: Nancy O. Albert from a project commissioned by the Middletown Housing Authority

Nancy O. Albert was university coordinator and director of the Russell House at Wesleyan University. She had been project photographer for the Hartford Studies Project at Trinity College since 1992. Her work has been widely exhibited in area galleries. She was the HRJ photo editor.

Explore!

“How Segregation Happened in West Hartford,”

“The Federal Government and Redlining in Connecticut,”