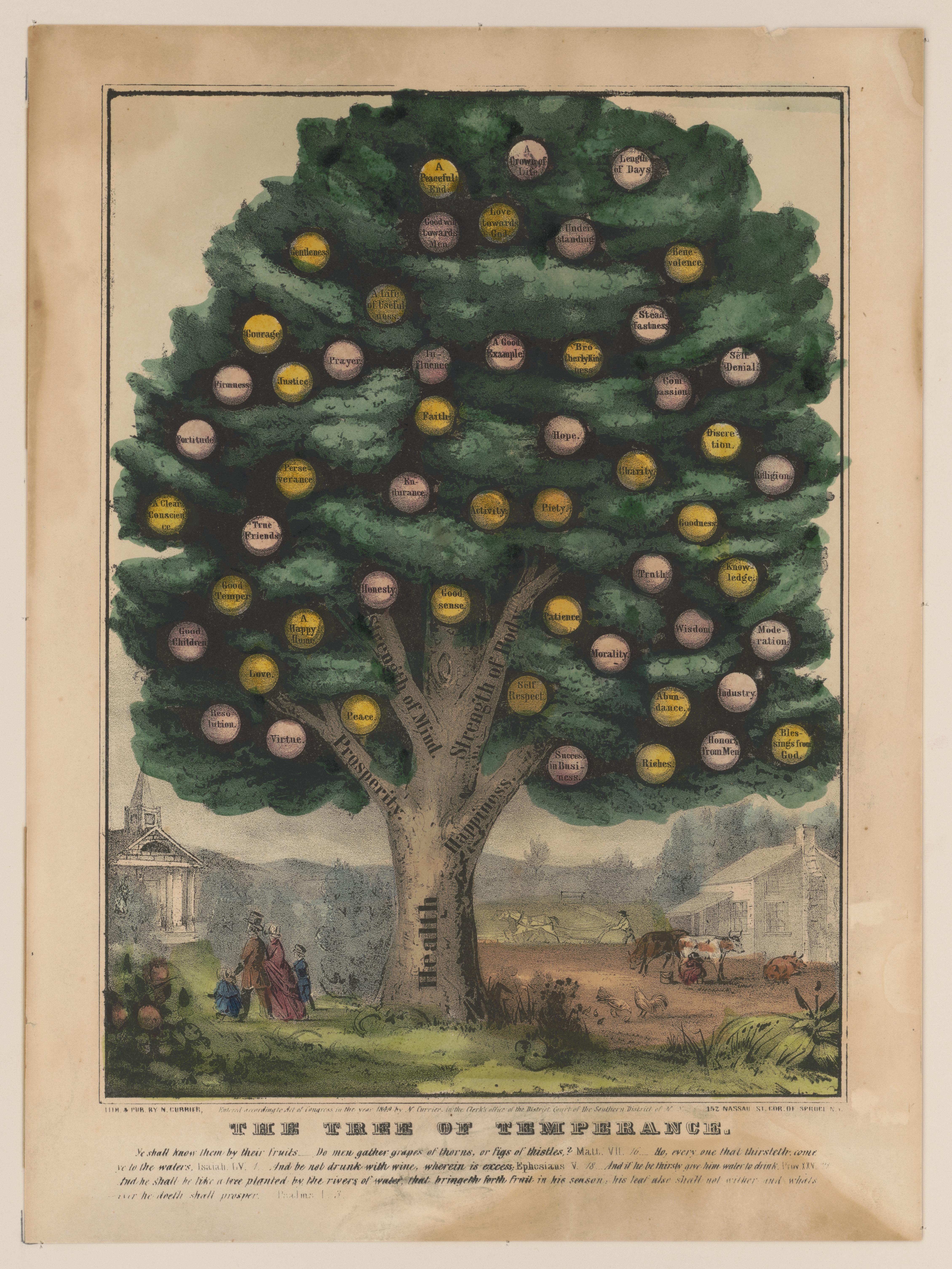

“Tree of Temperance,” N. Currier, 1849, depicts the evils of indulging in strong drink. Library of Congress.

By Alexander Dubois

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

Recalling his childhood in Wethersfield, John Marsh wrote that “the town was settled, as were most of the towns in Connecticut, with hard drinkers.” Marsh’s autobiography, Temperance Recollections: Labors, Defeats, Triumphs(C. Scribner & Co., 1866), documents the evils long associated with alcohol consumption. From the colonial period through the early 1800s, liquor was served to workers and farm laborers and prescribed as medicine. Barn raisings, town meetings, elections, and most social gatherings served as opportunities to indulge. But since the late 18th century, the problems associated with drinking had caused local, state, and church leaders to take notice. The images in this photo essay document the rocky road temperance advocates walked in Connecticut.

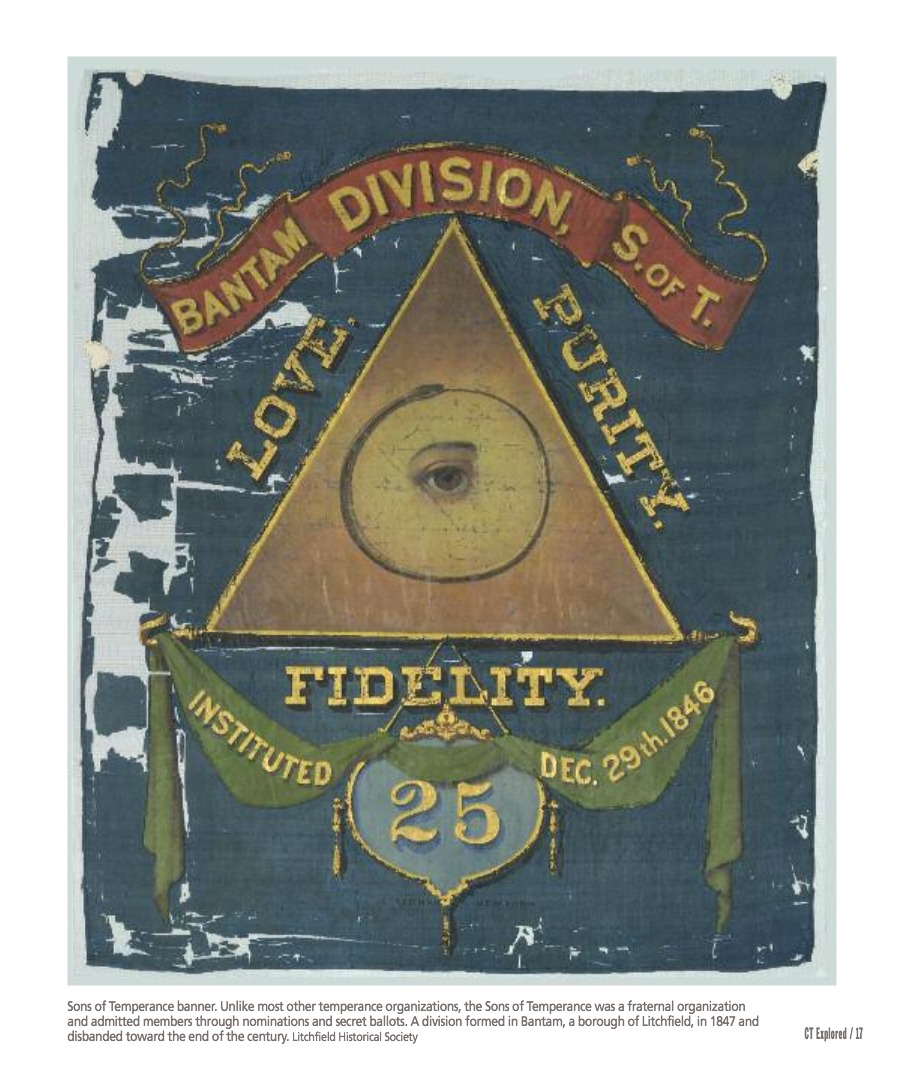

In 1789 town leaders in Litchfield started one of the country’s earliest recorded temperance organizations [See “Flying the Banner for Temperance,” Winter 2008]. In the group’s temperance pledge, a copy of which is held at the Litchfield Historical Society, the organizers decried the “immoderate use which the People of this State make of distilled spirits” and vowed to conduct their business without the use of liquor “as an article of refreshment.” As did many early temperance advocates, the Litchfield Temperance Association targeted the “evils” of distilled spirits but did not advocate giving up all alcoholic beverages.

The rhetoric around temperance changed to a message of abstinence in the early 19th century as clergymen took up the cause. In 1806 the Reverend Ebenezer Porter of Washington, Connecticut, delivered a sermon called “The Fatal Effects of Ardent Spirits.” Porter’s widely circulated address is credited by James Rohrer in The Origins of the Temperance Movement: A Reinterpretation(Cambridge University Press, 1990) as initiating a “clerical investigation of the liquor problem.” Church associations urged members to circulate abstinence tracts and push for stricter intoxication and licensing laws. Bolstered by a period of religious revival and growing reform sentiment, temperance became a national movement with the founding of the American Temperance Society in Boston in 1826, the same year that the society’s co-founder, the Reverend Lyman Beecher, delivered his popular “Six Sermons on Intemperance” in Litchfield.

The rhetoric around temperance changed to a message of abstinence in the early 19th century as clergymen took up the cause. In 1806 the Reverend Ebenezer Porter of Washington, Connecticut, delivered a sermon called “The Fatal Effects of Ardent Spirits.” Porter’s widely circulated address is credited by James Rohrer in The Origins of the Temperance Movement: A Reinterpretation(Cambridge University Press, 1990) as initiating a “clerical investigation of the liquor problem.” Church associations urged members to circulate abstinence tracts and push for stricter intoxication and licensing laws. Bolstered by a period of religious revival and growing reform sentiment, temperance became a national movement with the founding of the American Temperance Society in Boston in 1826, the same year that the society’s co-founder, the Reverend Lyman Beecher, delivered his popular “Six Sermons on Intemperance” in Litchfield.

The state of Maine passed the first prohibition laws in the country, in 1851. On the front lines of the temperance struggle, John Marsh traveled to Maine to “be an eye witness of the wondrous spectacle.” Other states soon followed Maine’s lead. Connecticut’s prohibition act, signed into law in June 1854, outlawed the sale of liquor for personal consumption. The law made exceptions for medicinal, mechanical, chemical, and sacramental use but required towns to appoint agents to approve and report all liquor sales.

While most states, including Connecticut in 1872, repealed these early temperance laws, Holland Webb in “Temperance Movements and Prohibition” (International Social Science Review, 1999) argues that “their eventual defeats were all that liquor’s opponents needed to redouble their efforts.” The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1873) and the Anti-Saloon League (1893) organized to lobby for prohibition on a national level, resulting in the eventual, though short-lived, constitutional prohibition of alcohol under the Eighteenth Amendment—an amendment that Connecticut, notably, never ratified.

While most states, including Connecticut in 1872, repealed these early temperance laws, Holland Webb in “Temperance Movements and Prohibition” (International Social Science Review, 1999) argues that “their eventual defeats were all that liquor’s opponents needed to redouble their efforts.” The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1873) and the Anti-Saloon League (1893) organized to lobby for prohibition on a national level, resulting in the eventual, though short-lived, constitutional prohibition of alcohol under the Eighteenth Amendment—an amendment that Connecticut, notably, never ratified.

Alexander Dubois is curator of collections at the Litchfield Historical Society. He last wrote “The Old Connecticut Game of Wicket” (Summer 2018).