(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

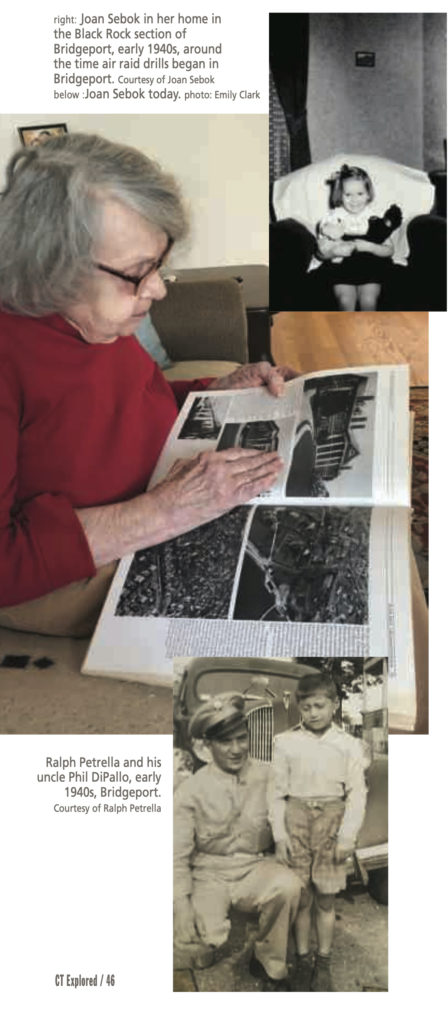

As a horn blew short bursts from an air raid tower near the Bullard Company, Joan Sebok hid in the inner hallway of her home in the Black Rock section of Bridgeport. Leaving homework unfinished on the kitchen table, the eight-year-old and her sisters huddled together as their father hung blackout curtains in the windows facing Schofield Avenue. They kept silent and still, she told me in a February 2020 interview, until a continuous “all clear” signal rang out.

Across town on Broadway Avenue in Bridgeport’s North End, young Ralph Petrella heard that same siren. Kneeling on the living room couch, he peeked out the window to see air raid wardens pass by, checking for compliance, he recalled during my March 2020 interview.

Now in their 80s, both Sebok and Petrella said they were unaware at the time of the true gravity of the wartime situation facing their families, though today, they say, that haunting sound remains with them. “Even now, if I hear anything like that ‘woo-woo,’ I remember,” said Sebok, 83. “But back then, we all just took it in stride.”

This year Connecticut marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, and those who grew up in Bridgeport in that era have not forgotten the vivid memories that defined their generation. As children on the homefront, they made their own sacrifices and added their own contributions to the war effort while holding onto a semblance of childhood.

What better way to spend a Saturday afternoon in 1944 than enjoying two-for-one movies at the Merritt Theater on Main Street? Or stopping by Collins Pharmacy for an ice cream at the soda fountain? “This was a wonderful place to grow up,” said Sebok. She recalled the pharmacist on Fairfield Avenue who adorned his walls with photos of neighborhood kids who had enlisted and theater proprietors who passed a collection plate for war bonds during intermission. Sebok recalled the war’s uniting everyone. “The whole community was involved. We all wanted to do our part,” she said.

That sense of civic duty, even among children, was a constant presence. Sebok smiled as she recalled bringing tin cans and scraps of aluminum to a local collection site in “my little red wagon,” believing they would be used to manufacture aircraft. Kay Besescheck, 84, also remembered collecting the tiniest foil pieces from cigarette packages. “We gathered anything we could put our hands on. And even at school, we had war saving stamps that we’d use to fill a book,” said Besescheck, who still retains that patriotic spirit decades later. Standing in what she calls her “Americana Room,” this long-time Bridgeport resident gestured toward medals of decorated relatives, flags that had covered the caskets of family members, and photos of those who served their country through the years.

top: Joan Sebok in her home in the Black Rock section of Bridgeport, early 1940s, around the time air raid drills began in Bridgeport. Courtesy of Joan Sebok; middle :Joan Sebok today. photo: Emily Clark; bottom: Ralph Petrella and his uncle Phil DiPallo, early 1940s, Bridgeport. Courtesy of Ralph Petrella

For teenagers attending Central High School in the 1940s, the absence of those enlisted young men was especially noticeable as prom season rolled around. Millie Bonomo, 93, remembered the spring of 1945, when “we couldn’t go to the prom! There were no guys around, no dates. It seemed everyone was in the service,” she said. That didn’t stop her and her friends from dressing up, though—albeit without nylon stockings, which “were so scarce because in wartime, nylons were used for parachutes.” “So guess what?,” she continued, “We painted our legs with leg makeup!” Bonomo laughed, adding how difficult it was to apply the orange-tinted “liquid stockings” evenly. “Imagine that!”

Despite the childhood nostalgia, the seriousness of the conflict was never far from home, especially when loved ones returned with injuries—or worse, lost their lives. Besescheck recalled losing a cousin, while Petrella, 86, remembered welcoming home an uncle who survived both the D-Day invasion and the Battle of the Bulge but was wounded at sea. Watching his Uncle Phil return from war, walking down Broadway Avenue, left an indelible mark in Petrella’s memory. “He was in uniform and carrying his duffel bag,” he said. “I remember getting teary-eyed because I knew his boat had been torpedoed. I was only 11 years old and so excited to see him.”

As the Bridgeport Telegram relayed news of triumph and defeat, children throughout the city withstood and persevered. “We all had to give preference to the war effort,” says Petrella, “and we did.” Such sacrifices eventually gave way to another sound that children like Sebok and Petrella will never forget: the sound of rejoicing on that long-awaited day of victory.

Emily Clark is a freelance writer and an English and journalism teacher at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge.

Explore!

Receive each beautiful and informative issue — Subscribe Today!

“A Pint-sized View of War,” by State Historian Walter Woodward, Winter 2014/2015

“Pulling Together at Home in World War II,” Spring 2010, Thomas J. Gworek’s memories of his childhood in Wethersfield

“If you don’t need it, DON’T BUY IT,” by Amber Degn, Fall 2003, about rationing in Windsor in World War II.

Read more stories about Connecticut at War and Childhood in Connecticut history on our TOPICS pages.