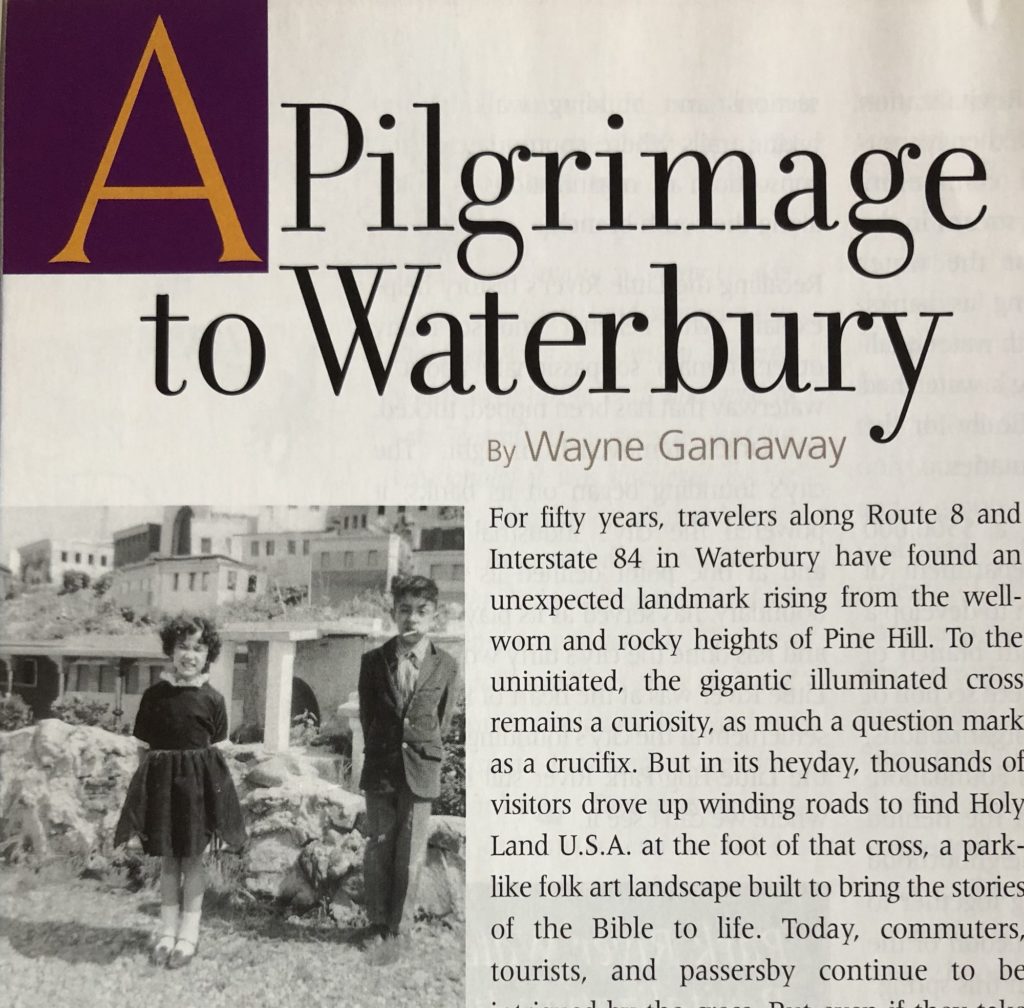

Visitors to Holy Land U.S.A., c. 1960s. The attraction drew up to 40,000 visitors a year. Lillian Martinez Collection, Mattatuck Museum

By Wayne Gannaway

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

For fifty years, travelers along Route 8 and Interstate 84 in Waterbury have found an unexpected landmark rising from the well-worn and rocky heights of Pine Hill. To the uninitiated, the gigantic illuminated cross remains a curiosity, as much a question mark as a crucifix. But in its heyday, thousands of visitors drove up winding roads to find Holy Land U.S.A. at the foot of that cross, a park-like folk art landscape built to bring the stories of the Bible to life. Today, commuters, tourists, and passersby continue to be intrigued by the cross. But even if they take the time to find their way to the stone gates of Holy Land, its dilapidated condition and abandonment to weather and vandals would leave them with more questions than answers. The shambling landscape on Pine Hill today won’t reveal much of the story of Holy Land U.S.A.; that can only be found in the vibrant community of Italian Americans in 1950s Waterbury.

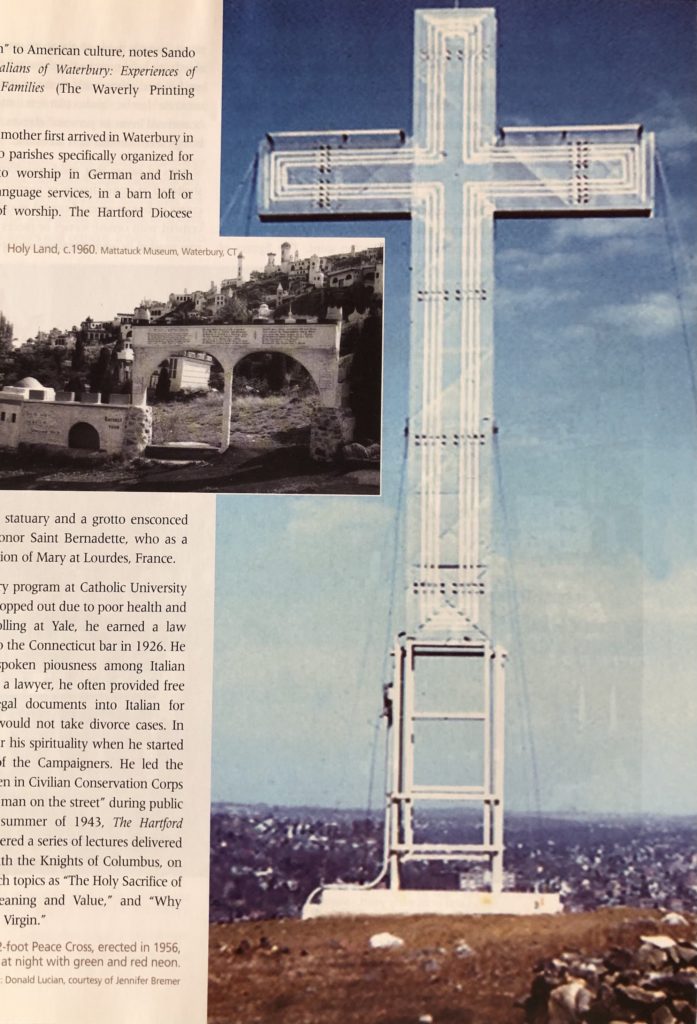

In raw weather in November 1956, John Greco, a devout Catholic and first-generation Italian American, along with fellow members of the lay group, Catholic Campaigners for Christ, raised a 32-foot, neon-bedecked crucifix on a Pine Hill bluff overlooking Waterbury. The cross was the brainchild of Greco and Anthony J. Coviello, an immigrant and fellow Campaigner. They named it the Peace Cross. It was intended to inspire citizens to keep prayer in their lives, but, with newspaper headlines blaring news of bristling Soviet aggression and expansion, the cross also reflected concerns about tyranny abroad during the Cold War-era.

right: the 32-foot Peach Cross, erected in 1956, glowed at night with green and red neon. photo: Donald Lucian, courtesy of Jennifer Bremer. inset: Holy Land U.S.A., c. 1960. Mattatuck Museum

The Peace Cross was the first element of Greco’s decades-long campaign to bring Christianity to the masses by providing concrete symbols of faith for them to contemplate. After erecting the cross, Greco conceived and built Holy Land U.S.A., a miniature recreation of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Largely handmade by Greco and volunteers from concrete, cinderblocks, and cast-off and salvaged materials, it grew out of an Italian tradition of homemade shrines to patron saints. At its apex in 1969, Holy Land U.S.A. consisted of more than 200 miniature buildings on 17 hillside acres. Throughout the 1960s and the early 1970s, more than 40,000 visitors a year made the pilgrimage to the tiny holy cities.

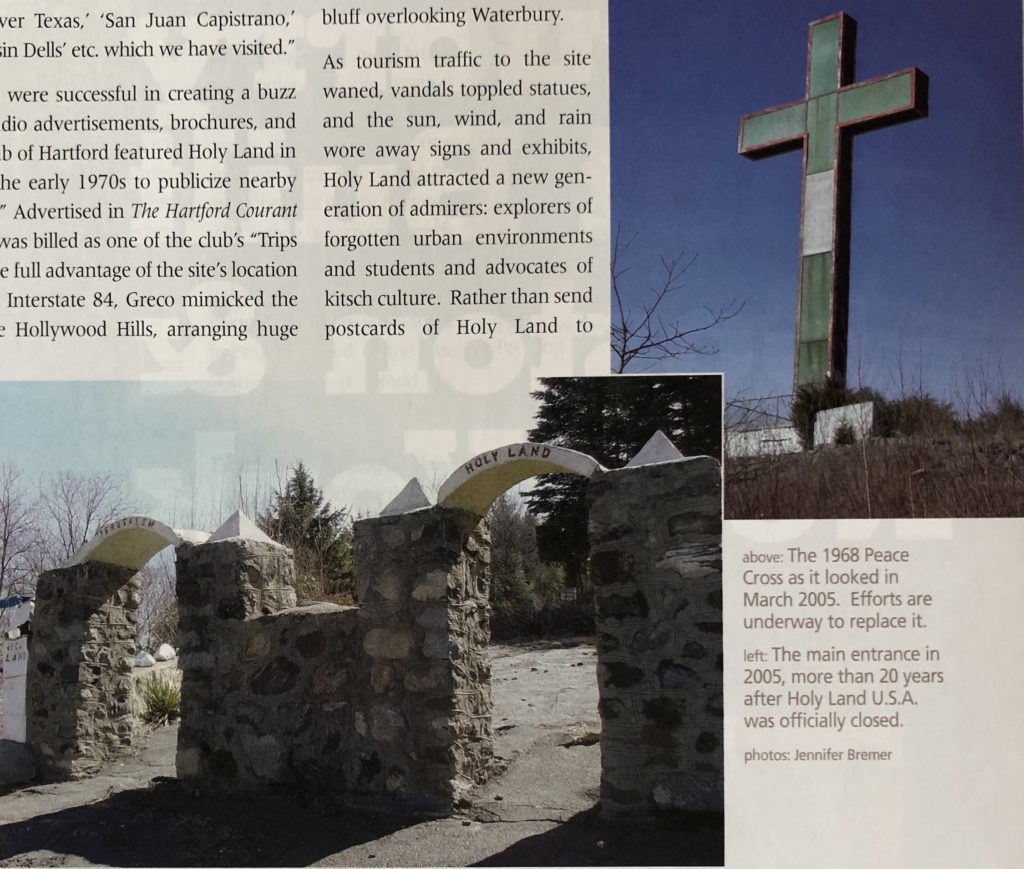

By the early 1980s, though, with Greco well into his 80s, Holy Land fell into disrepair. It was closed in 1984, two years before Greco’s death at 90. Today the crumbling remains attract mostly intrepid curiosity seekers and vandals. Though the Peace Cross still shines atop the hill (the current nine-ton, 50-foot stainless steel illuminated one is a replacement of the original), it too needs attention and efforts are underway to replace it yet again.

An Attraction Built on Tradition

Greco and many of the volunteers from Catholic Campaigners for Christ drew from their Italian heritage in envisioning Holy Land as a means of reaching out to the general public and popularizing the story of Jesus Christ. Its creators described themselves, as a large wooden sign at Holy Land’s main gate proclaims, as “A group of men who present a pictorial story of the life of Christ from the cradle to the Cross—it is our prayerful wish that the project will provide a pleasant way to increase your knowledge of God’s Own Book and bring you closer to Him.”

John Greco was born in Waterbury in 1895 to Italian immigrants Raffaela and Vincenzo Greco, a shoe repairman. Between 1890 and 1900, the population of Italians in Connecticut grew from 5,000 to more than 55,000. Many brought with them their language, customs, and religion, which didn’t make it easier for them to assimilate themselves in society. Like other immigrant groups, Italians in Connecticut and elsewhere in America faced economic and cultural isolation.

Perhaps reflecting the challenging economic conditions faced by immigrants (and others; the country experienced a major depression from 1893 to 1897) at the turn of the century, the Greco family came back to their home village of Torrella dei Lombardi, Avellino in southern Italy when Greco was very young, but they returned to Waterbury when he was 13. By then, Greco had absorbed firsthand the culture of Italy and the values and doctrines of the Catholic Church unfiltered by the necessity of “fitting in” to American culture, notes Sando Bologna in his The Italians of Waterbury: Experiences of Immigrants and Their Families (The Waverly Printing Company, 1993).

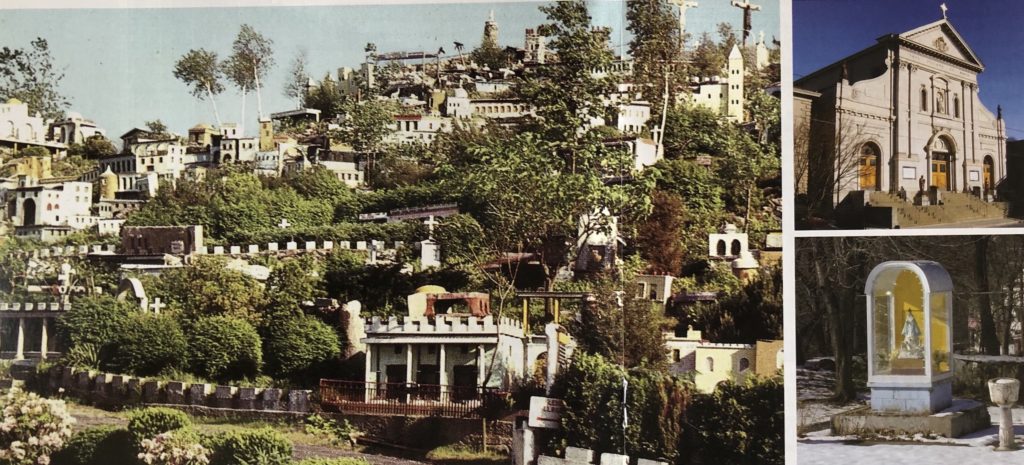

When Greco’s father and mother first arrived in Waterbury in the 1890s, there were no parishes specifically organized for Italians, leaving them to worship in German and Irish parishes or, for Italian-language services, in a barn loft or other makeshift place of worship. The Hartford Diocese eventually accommodated this important constituency and by 1923 had established three Italian parishes with a combined membership of more than 20,000, according to Bologna. Greco and his family were life-long members of Our Lady of Lourdes, the first church built for Italians in Waterbury. Dedicated in 1909, the church deployed life-sized statuary and a grotto ensconced below the sanctuary to honor Saint Bernadette, who as a child witnessed the apparition of Mary at Lourdes, France.

left: Holy Land U.S.A. in its early years. Mattatuck Museum. top right: Our Lady of Lourdes, dedicated in 1909, was the first church built for Italians in Waterbury. bottom right: A typical yard shrine. photos: Wayne Gannaway

Greco entered the seminary program at Catholic University in Washington, D.C. but dropped out due to poor health and financial constraints. Enrolling at Yale, he earned a law degree and was admitted to the Connecticut bar in 1926. He was known for his soft-spoken piousness among Italian Catholics in Waterbury. As a lawyer, he often provided free services and translated legal documents into Italian for immigrant neighbors; he would not take divorce cases. In 1930 he found a vehicle for his spirituality when he started the Connecticut chapter of the Campaigners. He led the group in proselytizing to men in Civilian Conservation Corps camps and jails and to the “man on street” during public lectures. Throughout the summer of 1943, the Hartford Courant announced and covered a series of lectures delivered by Greco, in partnership with the Knights of Columbus, on the Waterbury Green on such topics as “The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass,” “Prayer, Its Meaning and Value,” and “Why Catholics Honor the Blessed Virgin.”

Greco’s impulse to build Holy Land U.S.A. in the 1950s stemmed from the Roman Catholic and Italian traditions that shaped him and his fellow Campaigners. Back home in Italy each village had its own saint to celebrate. In this country Italian-Americans honored saints by creating statuary, grottos, nativity scenes, and passion plays they displayed at mass, at festivals, and at their homes. Thus Greco’s desire to give public expression to his spirituality was by no means unusual.

Italian Americans created lasting traditions of ornamented seasonal yard shrines and permanent altars, where one could daily express gratitude to his patron saint. The figures of saints, usually made of plaster or cement, were readily available from local merchants; those who bought them typically embellished them with common yard decorations such as concrete lambs, birds, planters, and plastic flowers, and household items or personal objects, thus making the sacred beings seem familiar and accessible.

Statues of saints that reside outdoors all year are typically sheltered in small chapels or grottos. More skilled craftsmen create elaborate cases of carved wood with glass fronts or use cement with ornate stones or pieces of broken glass or mirrors pressed in, giving texture and sparkle to the rustic shell. Those less handy can readily assemble the tried and true “Mary in a half-shell,” or “bathtub Madonna,” consisting of a statue of a saint housed in a bathtub standing on end and partially sunk in the ground. According to Joseph Sciorra, in his article “Yard Shrines and Sidewalk Altars of New York’s Italian-Americans,” the choice of materials for making the shrines, and their arrangement, is not random, but rather “reflect community-recognized models and traditional aesthetic preferences” (Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, Vol. 3, 1989, pp. 185-198). The yard grotto, according to Sciorra, makes particular use of stones and cement, lending “itself to the creation of a total environment that is ornately landscaped and is often populated with figures of adoring children and wild animals, which add life to this bucolic diorama, a frozen moment in sacred time.” Holy Land was much like the yard shrine, writ large.

Holy Cities at the Foot of the Cross

After deciding on Pine Hill as the most visible point in Waterbury, Greco and Coviello began planning the first phase of the project, the Peace Cross. They secured permission from land owners, designed the cross, and solicited donations of materials and labor from local merchants, including the stringing of electrical lines by Connecticut Light & Power.

Greco and Coviello provided the leadership, but they did not work alone. They used their influence within the Catholic lay community to recruit the muscle required to raise the cross. In her unpublished 1991 senior thesis, “An Italian Hill Town with a Neon Cross: The Short-Lived Alchemy of Holy Land U.S.A,” Yale student Cristina Mathews noted that the Peace Cross project was a rare instance in which Waterbury’s Italian and Irish Catholics worked together on a project. Greco’s Campaigners for Christ joined forces with the more ethnically mixed Waterbury Holy Family Passionist Retreat League to carry the cross, tons of concrete, and other building materials by hand to the top of Pine Hill.

The design of the cross, according to an article in the Waterbury Republican-American, included green lights as a shining symbol of hope, and red lights that were a reminder of the “fire and blood” of the tyranny of Soviet communism behind the Iron Curtain. In this way, Mathews observed, the Italian community in Waterbury was “able to join general American concerns with those specific to Catholics.” When it was finally assembled, electrified, anchored in tons of concrete, and secured against the winds with steel cables, the Peace Cross, Mathews wrote, “stood as a triumphal mark on Waterbury” and served as a local expression of hope against foreign threats. The public responded favorably to the Peace Cross. The Republican-American reported that 1,000 people attended the dedication in November 1956.

Soon after his success in raising the Peace Cross, John Greco began planning for Holy Land, a landscape environment that, according to Mathews, in contrast to the cross, “was miniature rather than oversized, had to be strolled through rather than gazed at, was detailed and multifaceted rather than simple and easily comprehended.” Greco, with help from the Campaigners, began by studying maps, photographs, and the Bible to make Holy Land as accurate as possible; a later research trip to Jerusalem and Bethlehem gave Greco additional impressions—along with soil and rocks—to add to his exhibits.

top right: The 1968 Peach Cross as it looked in March 2005. left: The main entrance in 2005, more than 20 years after Holy Land U.S.A. was officially closed. photos: Jennifer Bremer

While maintaining a full-time private law practice, Greco spent weekends and weekday afternoons laboring on the windy, rocky terrain of Pine Hill, usually with the help of volunteers. He funded the project through his own savings and an inheritance from his brother. Perhaps reflecting his limited resources, he constructed the exhibits with easily obtained building materials, salvaged architectural features, cast-off appliances, and other obsolete consumer goods. Greco and his volunteers transformed tons of cement, stones, cinderblocks, bricks, and clay into a dramatic, if somewhat rustic and rambling, landscape of visual diversity and contrasts.

Visitors could gaze up at the three large crosses at Calvary set back on the crest of a hill or peer into the dim cave of the Nativity grotto. They could contemplate the messages from an over-sized Bible painted red, white, and blue and opened to the Ten Commandments, or decipher the mixture of such salvaged objects as old televisions, radios, hand railings, soup pots, and other domestic odds and ends that were cobbled together to create many of the exhibits and edifices. Visitors could stand in the bright sunshine and take in the view of Waterbury, or make their way through a 200-foot-long cinderblock tunnel grimly recreating the catacombs, with store mannequins standing in for Christian martyrs.

Not all of Greco’s materials were mundane or cheap. In a 1960 Christmas-season tour of Holy Land, Mary Jean Bliss noted in the Hartford Courant (December 25, 1960) that a “statue of the Good Shepherd, imported from Italy at a cost of $1,000, is seen rescuing a lost sheep trapped in a crevice.” Local churches or Catholic organizations donated exhibition materials. Pillars from the 1964-65 World’s Fair’s Vatican pavilion made their way to Holy Land after the fair ended.

The first completed section of Holy Land U.S.A. was inspired by Greco’s experience in fabricating and promoting the Nativity scene. In 1943, Greco and the Campaigners had lead a “Put Christ Back in Christmas” campaign that began a Yuletide tradition of fashioning a Nativity scene on Waterbury’s town green. (The town continues that tradition today.) Mathews points out that Greco, as well as Catholics in general, were also concerned about the condition of the institution of the family during the social turbulence of the 1960s.

“Bethlehem Village,” as Holy Land was originally named, was officially dedicated and opened on December 11, 1958. The Waterbury Republican-American described the brand-new attraction as consisting of “more than 125 buildings of plywood and stainless steel. Colored lights have been installed at the ‘village’ which will be open throughout the year.” Bliss described the crèche as “eight feet high and 18 feet deep. Within are three Italian statues of the Christ Child, Joseph and Mary. There are many small statues of animals and the Three Magi.” Taking note of the prominence given to Bethlehem and the Nativity scene in “Manger Square,” directly in front of the main gates, Mathews observes that “Bethlehem Square” invited modern families to celebrate the traditional family—and attendant responsibilities—in the presence of Joseph, Mary, and the Baby Jesus. “Seeing a ’realistic’—if diminutive—replica placed the events of the Bible in an entirely different light, made them seem more real: it became possible to believe that they happened to real people,” Mathews observes.

Beyond the traditional values reflected in the Nativity display, the Marriage exhibit (located in a cypress grove), or the Grotto of the Holy Family, Greco also embraced social justice as a tenet of his faith. In a precursor to the Peace Cross, in 1954 Greco and the Campaigners had created a parade float featuring a cross and a sign reading “Segregation is Unamerican, Unchristian, and Ungodly,” according to Mathews. At Holy Land, Greco prompted visitors to contemplate the charity and grace of Christ with inscriptions on tablets of concrete scattered around the site, emphasizing the equality of all humans: “We Are the Body of Christ. If One Member Suffers, All Members Suffer.”

From Christian to Kitsch

To effectively reach out to the general public and educate them about the Bible in a topical, modern context, Greco developed Holy Land as a convenient attraction with directional signs, parking, refreshment stand, and a picnic area. He was no doubt aware of other tourist destinations attracting vacationing families. Mathews points out that Disney Land was opened in 1955. Indeed, Mathews notes, tourists from Columbus, Ohio wrote to Greco in 1964 that “We have visited 44 of our states, most of them several times, but have seen very few things that would excel what you have there. That statement includes ‘Disney Land,’ ‘Six Flags over Texas,’ ‘San Juan Capistrano,’ ‘Knotts Berry Farm,’ ‘Wisconsin Dells’ etc. which we have visited.”

Greco and the Campaigners were successful in creating a buzz about Holy Land through radio advertisements, brochures, and publicity. The AAA Auto Club of Hartford featured Holy Land in its marketing campaign in the early 1970s to publicize nearby trips to “Help Conserve Gas.” Advertised in the Hartford Courant in July 1974, the attraction was billed as one of the club’s “Trips for Tankful Travelers.” To take full advantage of the site’s location just off of Route 8 and later Interstate 84, Greco mimicked the iconic landmark sign in the Hollywood Hills, arranging huge white letters to announce Holy Land U.S.A to passing motorists.

In 1972, the Archdiocese of Hartford assigned two nuns from the Religious Teachers Filippini to assist John Greco in operating Holy Land. Based in a convent just outside the gates of the site, the nuns gave tours and helped with upkeep. In fact, the nuns were also caregivers for the now elderly Greco. A life-long bachelor, he lived at the hilltop convent. Despite help from the nuns, the fate of Holy Land was bound to Greco himself, and when he became frail, so too did Holy Land. The site closed in 1984 and was deeded to the Religious Teachers of Filippi when Greco died two years later.

Since Greco’s death, many plans and campaigns to save Holy Land have been proposed. In press accounts and fundraising brochures, proponents have sketched out visions of a refurbished Holy Land U.S.A. with a new visitor center. In the late 1980s, advocates for preserving the site as an important folk art environment staved off demolition of the site by organizing demonstrations and applying public pressure on local church officials, the Religious Sisters of Filippi, and the remaining members of the Catholic Campaigners for Christ. While new plans are underway to replace the 40-year-old Peace Cross, the ruins of Holy Land U.S.A. and the visions of John Greco continue to molder on the rocky bluff overlooking Waterbury.

As tourism traffic to the site waned, vandals toppled statues, and the sun, wind, and rain wore away signs and exhibits, Holy Land attracted a new generation of admirers: explorers of forgotten urban environments and students and advocates of kitsch culture. Rather than send postcards of Holy Land to friends and relatives describing their experiences at the lively attraction, today’s intrepid visitors (whose presence at the long-closed site constitutes trespassing) post their reactions and digital images and video on Web sites and blogs. The creators of the Holy Land page on roadsideattraction.com aptly capture the draw of the fallen attraction to modern enthusiasts: “We return—again and again. We’re not sure why.”

Wayne Gannaway was the construction grants coordinator with the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism.

Explore!

Read more stories about Immigration in Connecticut on our TOPICS page

More stories about Waterbury:

“The Brass City Manufactures for Victory”

“Longer-Lasting Than Brass: Waterbury’s City Hall Restored”

“Waterbury: Three Generations in the Newspaper Business”