Illustration from “On Bonesetting, so called, and its relation to the treatment of joints crippled by injury, rheumatism, inflammation, &c,” Wharton Peter Hood, 1871. Yale University, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

By Maureen Welch and Alicia Wayland

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Dr. Sweet forced Mary’s hand upward, then down, then to the left and right, each motion accompanied with a sound as of a bundle of sticks breaking. In an instant after the last movement, the bones were in place….”

In 1808 when Benjamin Silliman took his mother Mary to bonesetter Benoni Sweet to treat the botched surgery a physician had performed on her broken wrist, he was a professor of chemistry at Yale College and already known for his scientific achievements. The decision by the well-educated Silliman to put his mother in the care of a layman without scientific credentials was not unusual for the time. Medical practice was still guided by the “heroic principles” of bloodletting, purging, and blistering, and men and women of all classes relied on the skills acquired by lay practitioners for treating diseases, guiding them through childbirth, and setting broken and dislocated bones.

Clarence Meyer writes in his self-published 1985 compilation of herbal folk remedies American Folk Medicine that “For some 200 years after the first colonists arrived, there were no hospitals or medical schools. Old World recipes printed in almanacs and newsprints were the main source of medical information available to the general public.” The title of “doctor” was earned by an apprenticeship of three years with an established physician, riding with him on rounds and studying his medical books, culminating in a certificate of proficiency. Without standardization of requirements, however, the public willingly bestowed “doctor” on any laymen who appeared to have sufficient skill to achieve success as apothecaries, midwives, and bonesetters.

By the mid-19th century, medicine had become more professionalized with more rigorous training and new technologies, effectively cutting out apothecaries and midwives from the practice of medicine, although purveyors of nostrums and patent medicines were widespread. Bonesetters, however, continued to fill a void in medical knowledge before the development of X-rays and the specialty of orthopedics. Their hands-on training began at an early age, usually with an older family member. They did not operate on patients, but through manipulation and sometimes re-breaking poorly set bones they were often able to perform corrective measures with a high degree of skill and success.

In this period, trained physicians competed with bonesetters for patients. In his 1850 work Lessons from the History of Medical Delusions, Worthington Hooker, M.D. laments, “[A] delusion of the present time is the very prevalent disposition to put a low value upon the medical profession. The accumulated experience of medical men is often spoken of as being almost worthless, and the claims which medicine has to be ranked among the sciences are often openly disputed.”

British physician Wharton Peter Hood cut to the heart of the tension between physicians and bonesetters when he advised his colleagues in 1871, “Few of you are likely to practise without having a bone-setter for your enemy; and if he can cure a case which you have failed to cure, his fortune may be made and yours marred.”

In his 1910 work Sprains and Allied Injuries of Joints, eminent Oxford physician R.H. Anglin Whitelocke reserves his highest contempt for “a class of persons with little or no scientific training or interests,” who are “unregistered, irresponsible,” and equally damnable as “wiseacres.” Whitelocke was referring to bonesetters, practitioners of an occupation that sounds prosaic to contemporary readers but that held a valid place in American medical care through most of the 18th and 19th centuries. New England’s particularly strong reputation for high-quality bonesetting owes much to “the Bonesetter Sweets,” a family based in Connecticut and Rhode Island that maintained the tradition of for 10 generations.

For their part, the Sweets moved easily between their farm fields and their trade, setting bones almost as a sideline to their work on the land until the ninth generation went into practice. Then the family legacy gave way to early 20th-century expectations of the medical profession, which demanded college degrees and hospital residencies.

The Connecticut Sweets landed in Lebanon by way of North Kingston, Rhode Island, and, before that, Salem, Massachusetts. John Sweet and his wife Mary came from Wales to Salem in 1630. Roger Williams, the pastor of the Salem church, was banished from Massachusetts in late 1635 for his unorthodox religious views, and the Sweets followed him to Rhode Island where Williams had founded a new colony for dissidents in 1637. Beginning with John’s son James, the next three generations of Sweets would garner a local reputation for bonesetting in their North and South Kingston environs. In each generation a son took up bonesetting, transmitting his knowledge in turn to one of his sons (and, later, at least one daughter). Of James’s nine children, only Benoni was known to practice bonesetting. Of Benoni’s six children, only James took up the mantle.

It was to be James’s son Job, representing the fifth generation of bonesetting Sweets, who would elevate the family’s reputation from local to national stature. Job was born in 1724 and lived in South Kingston his entire life. His skills as a bonesetter were put to urgent use during the Revolutionary War, when he was called to Newport to treat French officers. Job’s skills were evidently held in high esteem as Aaron Burr, then a colonel fresh from the success of the war, called on Job in particular to set his daughter Theodosia’s dislocated hip. Writer Martha McPartland describes Job’s visit to the eminent Burr as “reluctant.” He avoided fanfare by telling the family doctors to return at 10 the next morning to witness the procedure; when they arrived he had already successfully treated Theodosia and was well on his way back to South Kingston. Despite their estimable skills and reputation, the Sweets were known for their modesty and lack of showmanship.

Job had two sons who carried on the family tradition. Jonathan remained in South Kingston and fathered two more generations of Sweets in Rhode Island, ending with Benoni Sweet’s death in Wakefield in 1922. With the relocation of Job’s son Benoni to Lebanon, Connecticut, the “bonesetter Sweets” split into two lines. According to the History of New London County, Connecticut, With Biographical Sketches, Benoni was obviously gifted with the Sweets’ bonesetting talent, but nonetheless removed himself to Lebanon in 1793, “determined not to practice bone-setting more, but give his whole attention to farming.”

While the source of Benoni’s reluctance is not identified, the biographical sketch emphasizes that he could no more choose his calling than he could choose his lineage. “This resolution, however, he was unable to carry out, for a dislocated shoulder in his own neighborhood which baffled the surgeons forced him again into the practice of this his legitimate and natural calling, which he never afterwards abandoned during active life.…” The characterizing of Benoni as “reluctant” fits in with other descriptions of the Sweet men as humble gentleman farmers whose remarkable bonesetting work was only a sideline. Whether this image was purposely crafted by the Sweets or attributed to them as part of the “natural and intuitive” narrative of the bonesetting mystique, we do not know.

Despite the family’s reputation for humility, fame seemed to court the Sweets. Governor Jonathan Trumbull Jr. recommended Benoni Sweet to his friend Benjamin Silliman. Silliman’s mother Mary had broken her wrist when she slipped on ice and fell in January 1808. When Silliman visited her in Middletown in May, her left hand and arm were totally unusable. In The Way of Duty: A woman and her family in revolutionary America, Joy Day Buel and Richard Buel, Jr. described the 1808 encounter between Mary and Benoni Sweet:

Dr. Sweet examined the wrist and gave it as his opinion that he could realign the bones. His confidence inspired trust, Mary ‘did not shrink from the pain which the Dr. said would attend the breaking up of the cartilage,’ and the procedure followed forthwith. ‘Stimulus was offered,’ Benjamin recorded, ‘but she declined… .’ While Benjamin grasped her arm above the wrist, and offered resistance, Dr. Sweet forced Mary’s hand upward, then down, then to the left and right, each motion accompanied with a sound as of a bundle of sticks breaking. ‘In an instant after the last movement, the bones were in place… .’ Immediately afterward, at the direction of Dr. Sweet, Mary performed a series of maneuvers with her arm and hand which indicated a return to almost normal function.

Dr. Sweet charged $10 for this treatment, a sum that, while sizeable for the time, did cover the three weeks he spent attending Mary while she recuperated at the governor’s Lebanon home, during which time Benjamin courted the governor’s daughter Harriet, whom he later married.

Benoni and his wife Sarah Champlin had nine children. Of this generation of Sweets we have evidence that at least four siblings practiced bonesetting for a time. According to the History of New London County and an 1896 newspaper clipping, Benoni, Jr. practiced in Guilford, Stephen in Franklin, and Sally “for a time at Willimantic.” The most notable Sweet sibling from this generation was Charles, who was born in 1810 and was said to have started bonesetting at the age of 16. Charles became especially well known for his bonesetting skills, perhaps because he took his practice beyond the Sweet homestead in Lebanon and had offices in Hartford, Norwich, and Springfield, which he visited on a rotating basis.

In the mid-1800s, Charles extended the Sweet sideline into more of a business than his forebears did. Charles expanded his practice in Lebanon, purchasing a country store on the town green, the site of the present library. The front was leased to George D. Spencer, who continued to operate the store in the front, while the back contained Sweet’s “shop, steam works and necessary room for professional services.” He opened a “Remedial Institute” in a large house on land he owned across from the store where out-of-town patients could stay during their treatment and convalescence. The boarding house was also run in conjunction with George Spencer, who leased it with the agreement that for $125 yearly rent he was “to improve said Dwelling House as a Boarding House for the patients or persons under the care of said Sweet and said Sweet agrees to furnish as many Boarders as he can conveniently.” This mutually beneficial lease arrangement ran to April 1, 1859.

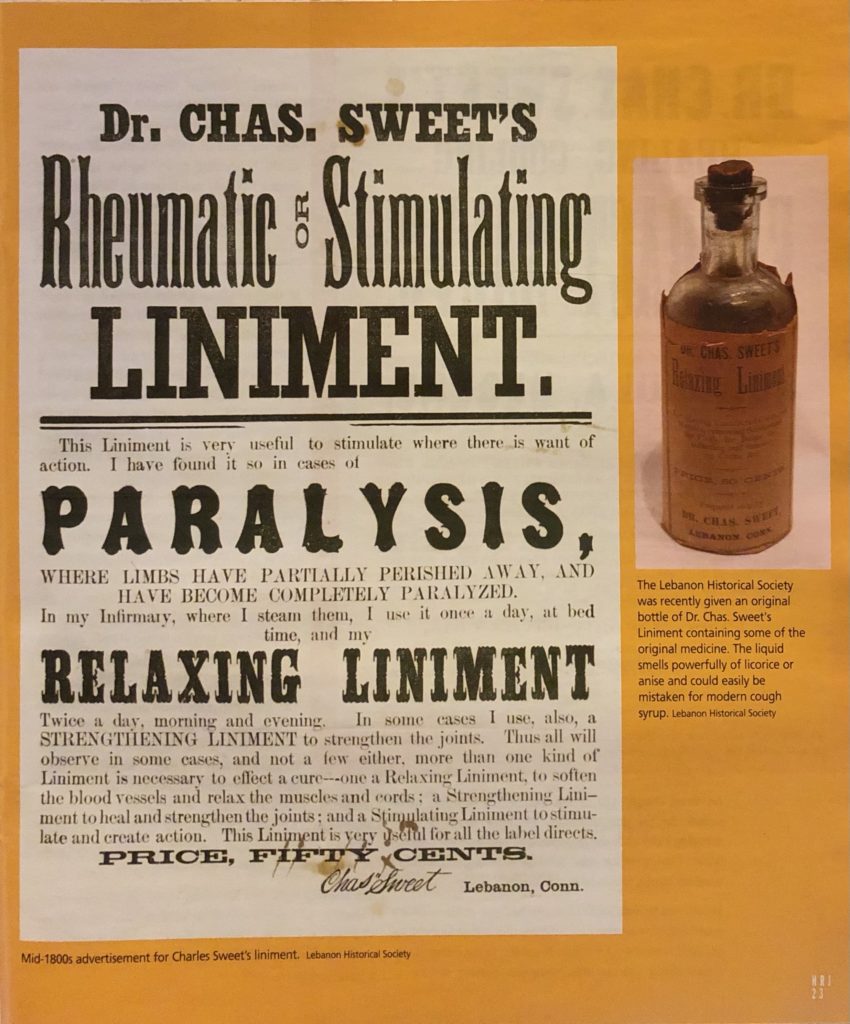

This generation of the Sweet family also developed medical liniments for commercial distribution. Charles had a “Rheumatic or Stimulating Liniment,” which was useful “where limbs have partially perished away, and have become completely paralyzed.” Charles’s advertisements also mention using steam as a treatment along with the liniment. Stephen had “Stephen Sweet’s Infallible Liniment,” bottled by Norwich, Vermont apothecary Edmund B. Richardson.

The boarding house, the advertising of the use of steam in his treatment, and the development of a product line indicate Charles’s knack for capitalizing upon what we might think of as the Sweet “brand.” That same business savvy led to his becoming a leading creditor in town, lending money to other people and earning returns on the interest.

Still, Charles is portrayed in period accounts more as a gentleman farmer than as a white-coated professional. While “the greater part of his time is devoted to this [bonesetting]calling,” still “In the intervals he prosecutes a limited amount of farming, which he does more for a pastime than for pecuniary profit.” Orra Parker Phelps, in her 1949 autobiography When I was a Girl in the Martin Box, writes of the time she fell off her family’s hay cart. Eleven days after she was bandaged by a Dr. Dean, that doctor told her father gravely that he “better take her to Dr. Sweet.” When Orra and her father arrived at Dr. Sweet’s house, they were told he was out hunting. Upon his return, “He said he guessed he’d eat before he fixed my wrist. Then he insisted that Father and I also have supper.” Dr. Sweet transitioned easily from the hunting field to the dinner table and on into the treatment room. Orra remembered, “Dr. Sweet came to me, took the two middle fingers of the injured hand, gave it the least little twitch and, there was my hand where it should be.”

right: an original bottle of Dr. Chas Sweet’s Liniment, left: mid-1800s advertisement. Lebanon Historical Society

Charles Sweet had three wives and nine children, two of whom, Charles, Jr. and John Henry Throop, became bonesetters. Charles, Jr. is known to have had an office in Hartford for a time, but he spent most of his life in Lebanon working alongside his father, who outlived him by three years. The older son, John H.T. Sweet, opened his office in Hartford in 1874 and practiced there for 80 years until his death in 1928. This eighth generation was the last to have its roots in a farming community. The sons of Charles Jr. and John H.T. Sweet were to go medical school: John H.T. Sweet, Jr. graduated from Tufts Medical School (now Tufts University School of Medicine) in 1912, while Charles, Jr.’s son Wallace graduated from Yale medical school some years later. The cousins went into the practice of orthopedic surgery together in Hartford in the mid-1920s. Wallace died of a ruptured appendix in 1930. John practiced for many years afterward, fathering the last of the Sweets to treat bone injuries, Elliott B. Sweet, who practiced in Hartford and West Hartford until the early 1980s.

Aloise Wirth, a bonesetter practicing in Rochester, New York, published a pamphlet in 1900 of patient testimonials, hoping to shore up his profession’s shrinking role by allaying the fears of a public who would “look with distrust upon men professing to heal wounds and cure diseases without the use of medicine.” Wirth’s testimonials, in addition to supporting the role of the bonesetter, occasionally take potshots at professional doctors as well:

New York, July 19, 1896. This is to certify that Mr. Aloise Wirth, of 68 Ontario street, Rochester, N.Y., cured our little girl (four years old) of a lameness that dated back from her birth, and was pronounced incurable by more than two dozen doctors, including several of the best known specialists in New York city. Her trouble was, one leg was more than one and a half inches short and on the verge of withering away. After a painless operation of less than one minute her leg was brought to its full length, so that she now walks perfectly safe. H.L. Brown, Bay Shore, N.Y.

By the time of the pamphlet’s publication in 1900, all-out war raged between “natural” bonesetters and other healers and the increasingly organized and professionalized medical community. The first medical school in the country had opened in 1765 in Philadelphia. Connecticut saw the Medical Society of New Haven County established in 1784, followed by the establishment of the State Medical Society in 1792 and by the founding of the Yale Medical School in 1813. The apprenticeship model that had dominated for two centuries was fading as degree programs took hold; medical students had access to new understandings of anatomy achieved through cadaver dissection. By the time the ninth generation of Sweets emerged at the turn of the 20th century, bonesetting had become largely a historical curiosity.

But the bonesetters’ legacy lingers. We can see evidence of their knowledge and skill in the practice of chiropractors and orthopedic surgeons, who have a science-based understanding of matters that many of the bonesetters knew intuitively. Today’s renewed interest in a return to “natural” and alternative treatments in part reflects a nostalgia and a longing for the kind of care the Sweet family provided for generations on their homestead in Lebanon.

Maureen Welch, a graduate of Trinity College, was an intern for CT Explored in 2003. Alicia Wayland was the historian for the Town of Lebanon.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s medical history in the Spring 2007 and Feb/Mar/Apr 2004 issues.

“An Early American Midwife’s Tale: Jennet Catlin Boardman,” Summer 2003

Get every issue! Subscribe/Buy the Issue