By Wm. Frank Mitchell (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

By Wm. Frank Mitchell (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

The Knights of Columbus, a national fraternal mutual aid organization, was founded in New Haven in 1882 to provide insurance protection for members’ families and to fight anti-Catholic bias. The organization’s success prompted President Dwight Eisenhower to write Supreme Knight Luke E. Hart in August 1954:

I am happy to send greetings to the Knights of Columbus on the occasion of the annual meeting of your Supreme Council… And this year we are particularly thankful to you for your part in the movement to have the words “under God” added to our Pledge of Allegiance. These words will remind Americans that despite our great physical strength we must remain humble.

The effort that led to this note did not represent a unique victory for the organization. With its founding, the Knights’ leadership redefined fraternal society norms by creating a hybrid mutual aid and philanthropic organization with an advocacy sensibility that sought acceptance of Catholic men in Protestant America as good Americans. More recently, their advocacy has included a well-funded and controversial campaign in defense of traditional marriage. In less than a century the Knights of Columbus graduated from immigrant protection society to financially and politically influential power broker.

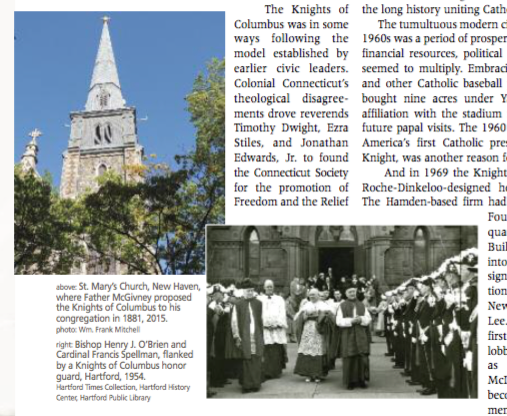

When the Knights of Columbus (the Order) was founded, mutual aid, benevolent, and fraternal organizations crowded 19th-century New Haven’s civic landscape. Irish, German, and Italian immigrants who began new lives in mid-19th-century New Haven could expect an indifferent welcome at best, jobs that required physical labor, and few options for injured workers and their families. Irish Catholic men found allies in The Red Knights, the Knights of St. Patrick, the Sons of Erin, and the Hibernian Provident Society. When Father Michael J. McGivney, a pastor at St. Mary’s Church, proposed in 1881 to the predominantly Irish parishioners a lay fraternal benefit society, they agreed to emphasize the concepts of family, parish, community, and nation in the new organization.

Those choices distinguished the Knights from New Haven’s many secular societies that focused on old European customs. The selection of Christopher Columbus—a Catholic explorer—as patron for their new organization grounded the Order in America’s founding and pointed toward the group’s future as a union of Catholic men embracing an American identity. Over the years, the Connecticut organization masterfully deployed the goodwill generated by this embrace of faith, patriotic service, and philanthropy in a civil rights battle against anti-Catholic bias.

The Knights of Columbus was in some ways following the model set by earlier civic leaders. Colonial Connecticut’s theological disagreements drove Reverends Timothy Dwight, Ezra Stiles, and Jonathan Edwards, Jr. to found the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom and the Relief of Persons Held in Bondage in 1791. The Society was the state’s first anti-slavery organization and a de facto fraternal, faith-based, advocacy organization.

With their freedom slowly increasing, emancipated blacks established their own benefit societies for protection and political agency. Members of New Haven’s African Ecclesiastical Society, an interracial Bible study group with civil rights and mutual aid expressions, founded the Temple Street Church and argued for full citizenship as tax paying residents. They planned on America’s accepting them as prayerful, family-oriented, citizens no matter how long that might take.

With their freedom slowly increasing, emancipated blacks established their own benefit societies for protection and political agency. Members of New Haven’s African Ecclesiastical Society, an interracial Bible study group with civil rights and mutual aid expressions, founded the Temple Street Church and argued for full citizenship as tax paying residents. They planned on America’s accepting them as prayerful, family-oriented, citizens no matter how long that might take.

By its 25th anniversary the Knights of Columbus was ready to engage the nation. Legislation supporting a memorial fountain to honor Christopher Columbus in Washington, D.C. moved quickly through Congress and received presidential approval. The unveiling five years later in 1912 succeeded in showcasing member patriotism, the Order’s evolving relationship to national politics, and the long history uniting Catholicism and North America.

The tumultuous modern civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s was a period of prosperity for the Order. The Knights’ financial resources, political strength, and cultural capital seemed to multiply. Embracing the history of Babe Ruth and other Catholic baseball players, in 1953 the Knights bought nine acres under Yankee Stadium. The Order’s affiliation with the stadium made it an ideal location for future Papal visits. The 1960 election of John F. Kennedy, America’s first Catholic president and a Fourth Degree Knight, was another reason for celebration.

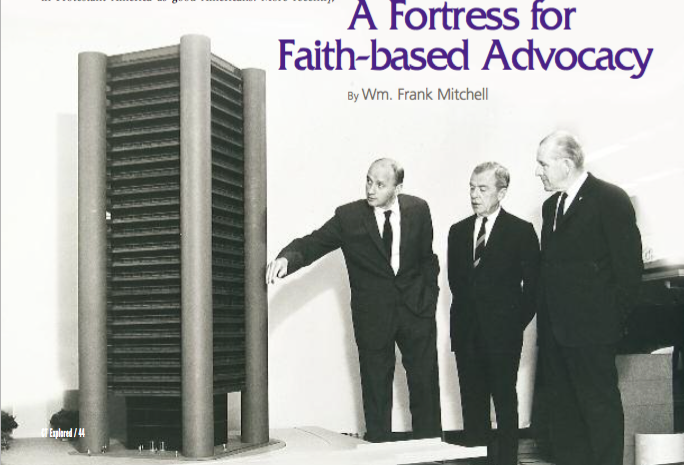

And in 1969, the Knights moved into a new 23-story Roche-Dinkeloo-designed headquarters in New Haven. The Hamden-based firm had recently completed the Ford Foundation’s Manhattan headquarters. The Supreme Office Building launched the Knights into the New Haven’s skyline and signaled the arrival of a generation whose ideal spokesman was New Haven mayor Richard C. Lee. Men similar to Lee were the first beneficiaries of the Order’s lobbying and support. The Order, as Supreme Knight John W. McDevitt acknowledged, had become more than a “fortress for members in a world hostile to the Catholic faith.” The world had grown more tolerant, a generation of veterans earned postwar prosperity, and the Knights’ insurance operation pushed toward $1 billion in insurance in force.

And in 1969, the Knights moved into a new 23-story Roche-Dinkeloo-designed headquarters in New Haven. The Hamden-based firm had recently completed the Ford Foundation’s Manhattan headquarters. The Supreme Office Building launched the Knights into the New Haven’s skyline and signaled the arrival of a generation whose ideal spokesman was New Haven mayor Richard C. Lee. Men similar to Lee were the first beneficiaries of the Order’s lobbying and support. The Order, as Supreme Knight John W. McDevitt acknowledged, had become more than a “fortress for members in a world hostile to the Catholic faith.” The world had grown more tolerant, a generation of veterans earned postwar prosperity, and the Knights’ insurance operation pushed toward $1 billion in insurance in force.

Wm. Frank Mitchell is curator of The Amistad Center for Art & Culture, a major contributor to African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014), and resident of New Haven.