(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2008/2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

More than a century before the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, the Bemans of Middletown, Connecticut were activists devoted to the struggle for equal opportunities for African Americans in the job market, schools, and the voting booth. Jehiel Beman, his second wife Nancy, his sons Amos and Leverett, and his daughter-in-law Clarissa were among the intellectual elite of the black middle class in Connecticut in the decades before the Civil War.

Jehiel Beman came to Middletown in 1830 from Colchester with his wife Fannie (Condol) and their seven children. Both were born free but were the children of slaves. Jehiel’s father, Caesar, was enslaved to John Isham of Colchester, who freed him in 1781, probably in exchange for his service in the American Revolution. Oral tradition has it that Caesar chose the surname Beman to emphasize his right to “be a man.”

Although the state’s gradual manumission of enslaved people began in 1784, slavery was not fully abolished in Connecticut until 1848. At the turn of the 18th century, Connecticut’s black population, both enslaved and free, was concentrated in agricultural areas. Beginning in the 1820s and 1830s, African-American families from Colchester, Lyme, and East Haddam began to migrate to Connecticut cities, especially Norwich, New London, and Middletown. The recent migration by young white men to the western frontier in search of land (Ohio and western New York) created an acute labor shortage throughout Connecticut. Unskilled workers were needed on farms and in river port towns such as Middletown, and also in cities, where opportunities were available for those free men and women who had trades, such as shoemakers, dressmakers, and carpenters.

According to the 1820 federal census, Middletown had 211 African American residents (208 free; 3 enslaved), most of whom were newcomers to town. No doubt this was a time of optimism and hope for the black community in Connecticut; in Middletown, Jehiel Beman exemplified this sense of optimism. In 1830 he accepted the call to be pastor for the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Zion Church, established in 1822, which was the third of its kind in the United States. The church had recently built a house of worship (originally located near the current southeast corner of Church and Pine streets). In 1830, Beman’s two eldest sons, Leverett Castor Beman and Amos Gerry Beman, were 20 and 18 years old, respectively. They had attended the Colchester Colored School before moving to Middletown.

In 1830 Amos attempted to enroll at Wesleyan University, but the administration of the Methodist institution bowed to pressure from Southern representatives on the school’s board of trustees and blocked his admission. He would have been the institution’s first African American student. Undaunted, Amos engaged a willing Wesleyan student to tutor him in private, but white students who opposed his participation in the college community threatened violence. Heeding his father’s advice that “the role of the black minister could be [pivotal]in the life of the black community and in movements for the elevation of the race,” Amos enrolled in Oneida Institute in upstate New York, and in 1841 he was appointed pastor of New Haven’s Temple Street African Church, where he served for almost 20 years.

Amos is by far the best known of the Beman reformers. He was active in New Haven during the Amistad trials and worked with nationally known abolitionists and civil rights leaders, including Reverend James W. C. Pennington, Simeon Jocelyn, Lewis Tappan, Charles Ray, and Henry Highland Garnet. [Read some of Amos Beman’s words in “Black Abolitionists Speak,” Spring 2011.]

Less is known about his older brother Leverett, and though his contributions were more local, they made history nonetheless. He lived in Middletown until his death in 1883 and earned his living as a shoemaker, the trade his father also practiced (in addition to his ministry). Leverett and his father rented a shop for $10 per year on Court Street, just down the hill from the family home on Church Street.

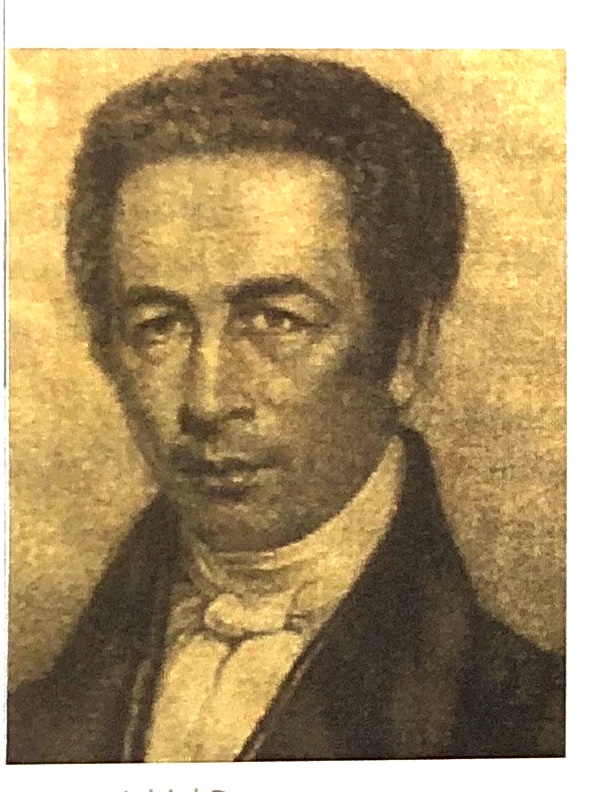

Leveret Beman’s 1847 map of the neighborhood he planned. His 1843 house is marked in the upper right corner.

In the spring of 1847 he walked into the town clerk’s office in Middletown and filed a survey map of land he owned on the edge of the city in a low-lying area known as Dead Swamp. Leverett had paid to have the land surveyed and divided into 11 house lots. His plan was to sell the house lots and develop a neighborhood where middle-class black families could own their own homes. Presumably, he may have offered the lots for sale to the general public, but he was primarily interested in selling property to some of the 200 or so African Americans then living in town—and turning a profit.

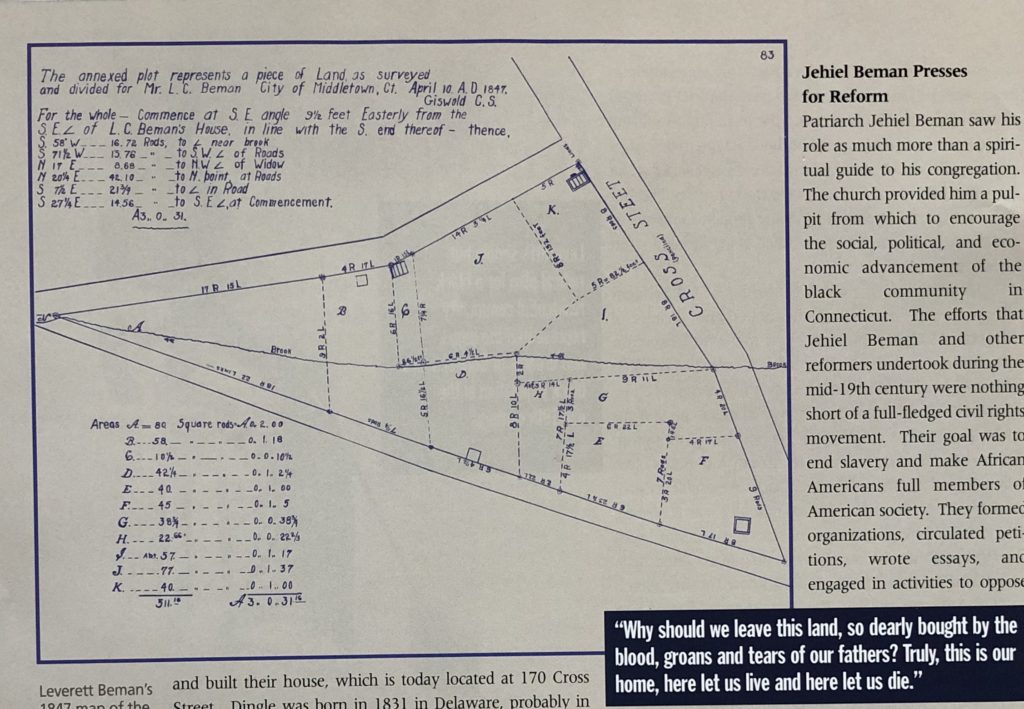

Leverett’s simple but radical plan for a black residential community represented the hopes and dreams of Connecticut’s black population in the mid-19th century for homeownership and the other rights it conveyed on their long, hard road to full equality. Only a few decades before, the nation’s founders had argued over whether voting rights and full citizenship should hinge on one’s status as a property owner. Housing available to African Americans often was substandard; moreover, few blacks were able to own property even years after slavery officially was abolished. The organization of Beman’s free black community was, therefore, highly unusual. It may be unique in Connecticut.

Today Leverett’s development is known as the Leverett C. Beman Historic District. This small triangle of land, bordered by the current Vine and Cross streets and Knowles Avenue, covers a mere four acres. Between 1830 and 1865, African Americans built 10 houses in the neighborhood; 5 of the original buildings are still standing. Leverett built his house at the corner of Vine and Cross streets in 1843, where the Neon Deli stood in 2009. Some of the houses in the neighborhood predate the development, built by the African Americans who helped established the A.M.E. Zion Church in the mid-1820s, among them George W. Jeffrey and Ebenezer Deforest. Some of the residents were newly freed or escaped slaves who made their way north from Southern states. Others were families who had relocated from the eastern part of the state and who made up the majority of Middletown’s black population.

Isaac B. Truitt bought 11 Vine Street in 1864 after renting it for several years. A seaman in 1860, he and his wife Eliza were born in Cedar Creek, Sussex County, Delaware about 1820. Around 1853 they came to Middletown, where their five children were born. A veteran of a black Connecticut regiment in the Civil War, by the mid-1870s Truitt was employed at Wesleyan College as a chimney sweep, cleaning out the stovepipes in student rooms and classrooms.

top: Isaac Truitt bought a house on Vine Street in the Beman Triangle. He worked as a chimney sweep at Wesleyan when this c. 1875 photo was taken for a college yearbook. below: Wesleyan’s college row, 1853. Wesleyan University, Special Collections & Archives

Amster and Emily Dingle, married in Hartford in 1855, bought Lots E and F in 1861 from Beman for $100 and built their house, which is today located at 170 Cross Street. Dingle was born in 1831 in Delaware, probably in New Castle County. Emily Peters, his wife, was born about 1833 in Chatham (East Hampton), Connecticut. Her grandfather had been a slave in Hebron. Dingle enlisted in the Twenty-ninth (Colored) Regiment Infantry, Company F, in December 1864, a few years after they built their house and their daughters Elizabeth and Mary were born. Dingle died from disease within a month at the muster camp in Fair Haven.

Many of the families illustrated the complex interrelationships among the small populations of Connecticut African Americans. Families intermarried within the Triangle and took in the relatives of their neighbors. Herod and Abigail Brooks, who came to Middletown from Lyme in 1828, built 9 Vine Street about 1840. Abigail was the sister of Asa Jeffrey, who already lived in the Triangle. Eunice Brooks, a relative, owned the house by 1835, and when she remarried in 1855, she lived there with her new husband, John Cambridge, and James and Orrice Brooks, both 19, the children of Herod and Abigail Brooks. James grew up, married John Cambridge’s daughter, and continued to live in the house. His sister Orrice married George O. Smith, who lived in the neighborhood at what is today 10 Knowles Avenue.

Patriarch Jehiel Beman saw his role as much more than a spiritual guide to his congregation. The church provided him a pulpit from which to encourage the social, political, and economic advancement of the black community in Connecticut. The efforts that Jehiel Beman and other reformers undertook during the mid-19th century were nothing short of a full-fledged civil rights movement. Their goal was to end slavery and make African Americans full members of American society. They formed organizations, circulated petitions, wrote essays, and engaged in activities to oppose slavery. Jehiel was a founding member of the Middletown Anti-Slavery Society in 1834. Nancy Beman, Jehiel’s second wife, and Leverett’s wife Clarissa organized the Colored Female Anti-Slavery Society in the same year; the society was only the second of its type in the country. The goal of the anti-slavery societies, which had both black and white members, was the immediate abolition of slavery. National leaders of the anti-slavery movement, including Boston’s William Lloyd Garrison, were regular visitors to the Beman home in Middletown. Jehiel wrote many articles for Garrison’s Liberator newspaper and for the Colored American. He also helped establish the A.M.E. Zion’s first national publication, Freedom’s Journal, in 1827.

The going was not easy, however. The activities of the local abolitionist groups were frequently met with violence, including a pro-slavery riot on Cross Street in 1835. Many moderate whites supported emancipation of American slaves but were comfortable only if the newly freed blacks were sent back to Africa, an idea encouraged by the American Colonization Society as early as 1816. Not surprisingly, most African Americans, including the Bemans, rejected the plan. The Bemans, with Amos as the group’s secretary, led an organized response to the colonization movement in 1831. In the group’s minutes, Amos articulated their views: “Why should we leave this land, so dearly bought by the blood, groans and tears of our fathers? Truly, this is our home, here let us live and here let us die.”

Members of the Middletown community, whites and blacks alike, actively participated in the Underground Railroad. Evidence confirms that Benjamin Douglas, a local white industrialist, opened his house at the head of the South Green to fugitive slaves. In an 1854 letter to Frederick Douglass, at the time the most prominent abolitionist in the United States, Jehiel assured him that, “The Underground Railroad… is in good repair… and open for business… at all hours of the day and night.” Henry W. Foster, who lived on Cross Street in 1860, is also recorded as being an agent of the Underground Railroad in the 1850s when he resided in Hartford. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it a crime to aid an escaped slave, put Middletown’s participants in serious jeopardy.

Reformers of the 19th century emphasized moral reform as a way of uplifting the black community in the eyes of the white populace. The Bemans felt that if African Americans lived sober lives and learned trades that made them industrious, contributing members of their towns, they would be accepted as complete participants in American society. In 1833, Jehiel founded the Home Temperance Society in Middletown. The primary directive of the organization was to promote complete abstinence from spirits, but the group also debated ways to make political gains for African Americans. Jehiel emphasized that education was the gateway to a better life for the next generation. After their move to Middletown, Jehiel enrolled his younger children at the Lyman C. Camp School in Middletown. Jehiel also helped recruit students for Prudence Crandall’s school in Canterbury, Connecticut in the 1830s. Later, Leverett created the Mental Improvement Society in 1870 to encourage education. Like Booker T. Washington, Jehiel encouraged African Americans to develop trades and practical skills to become productive contributors to the labor force. Through the state temperance group, Jehiel established an African American employment agency to help men find work.

The Home Temperance Society increasingly became a venue for political debate and action. State and national conventions of temperance groups in the 1830s eventually segued into Colored Conventions that organized at local, state, and national levels. In 1849 the first Connecticut Convention of Colored Men met in New Haven. Amos represented Middletown at subsequent state and national conventions and brainstormed ways to use political means to gain equal opportunities. The conventions’ primary efforts eventually focused on attaining basic rights: equality under the law, due process, including trial by jury, and the right to vote. For a very brief time at the beginning of the 19th century, Connecticut’s freed blacks were allowed to vote (though evidence has only found two men in Wallingford who were admitted to the voter rolls), a right taken away by the General Assembly in 1814. As leaders of the black abolitionist movement, the Bemans led a successful petition drive in 1847 for black suffrage, which was passed by the General Assembly. This time the right to vote was defeated by Connecticut voters in a state-wide referendum. Although appeals for suffrage were made time and again, African Americans in Connecticut were not granted suffrage until 1870 with the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. [See “No Taxation Without Representation: Black Voting in Connecticut,” Spring 2016.]

Middletown’s black population steadily declined after 1850. There were only 73 African Americans there in 1910. African Americans competed for jobs with the increasing number of immigrants, and the black middle class virtually disappeared. Few of the remaining blacks in Middletown lived in Leverett’s neighborhood. Those who worked in the service industry—housekeepers, servants, and chauffeurs—often lived with their employers. Others lived closer to where work was available for African Americans, either at the riverfront where men worked as stevedores and laborers or in rental housing in rural areas where many worked as farm laborers. By 1920 the neighborhood along Cross Street was predominantly home to white immigrants, first- and second-generation Swedish Americans and later Italian immigrants. Only five black individuals remained in Beman’s development, all on Knowles Avenue. By the time Middletown’s African American population hit an all-time low of 57 in 1920, European immigration had begun to decline, and job opportunities in New England increased. Middletown saw an influx of Southern blacks, brought here in the late 1920s and early 1930s, primarily to provide labor for Middletown’s brick industry.

Wesleyan University presently owns all but two of the properties in the Triangle, including the A.M.E. Zion’s former church. Students live in the historic residences. The A.M.E. Zion congregation adapted to meet the needs of an ever-changing community and is now located at the northeast corner of Wadsworth and West streets a half mile away. Wesleyan is taking the lead in continuing the research and exploration of this neighborhood by establishing an archaeology program in the Triangle to learn what artifacts can teach us about the rise and fall, the aspirations and frustrations, of Middletown’s 19th-century black community.

Liz Warner is a middle school history teacher at the Independent Day School in Middlefield. She researched, with Janice Cunningham, the Beman Triangle for the Connecticut Freedom Trail in 2002.

Explore!

Read more stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.