(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2020-2021

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

My very first byline was in Metroline, Connecticut’s gay community newspaper, in 1987. Just out of college, I was excited to see my name in print, except I only dared use my first and middle names, William John, as if I were Elton’s brother.

My fear of coming out fully on paper was rooted in the realities of living in the 1980s. The earliest articles I wrote were about the gay-bashing murder of Richard Reihl in Wethersfield in May 1988. Victim-blaming and “gay panic” defenses were common then. In the state legislature, we were called “lollipops” and “deviants.” The AIDS pandemic, which took so many from us, was routinely used as an excuse to discriminate against and demonize gay men.

Metroline offered a lifeline. By the time I came on board, it had already been around for more than a decade as MCC News, a newsletter for Hartford’s Metropolitan Community Church. The church, established in 1973, was a branch of the welcoming denomination for gay Christians started in California in 1968. In 1982, to reach a larger readership, MCC News became Metroline and the format changed to a magazine; in 1983, the publication went biweekly. Metroline, which was free, could be found in bars and gay-friendly businesses throughout the state and western Massachusetts. The issues went fast, often on the day of delivery.

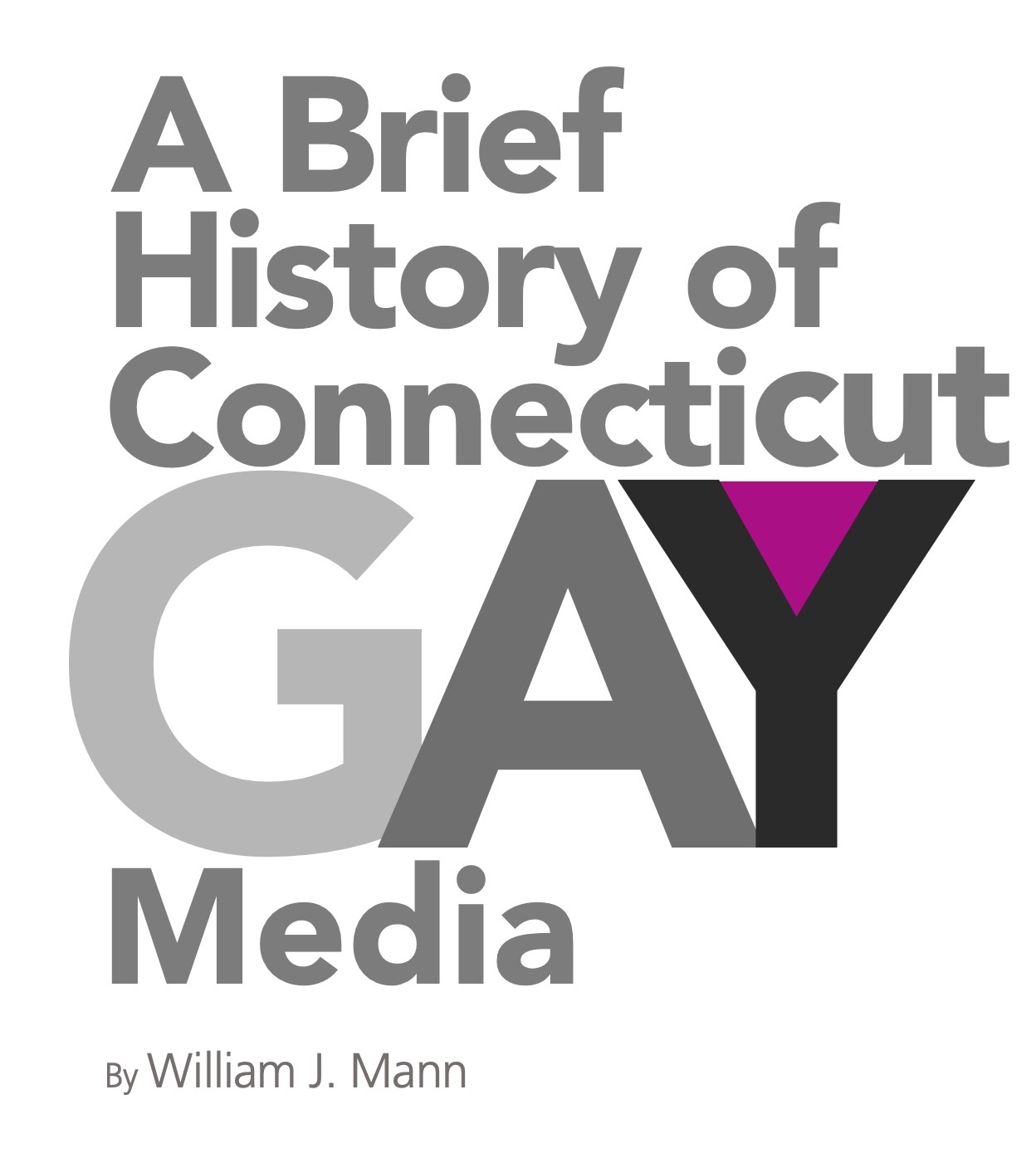

Metroline wasn’t the first gay publication in Connecticut. The Griffin printed its first issue in May 1970—less than a year after the Stonewall uprising in New York. The Griffin reported on that event, arguing that “the ten days of rioting last summer in NYC” proved that gay people would “fight if cornered or attacked.” The Griffin was published by the Kalos Society, Hartford’s “homophile organization,” as it described itself, whose agenda was summed up in one early issue as the “unqualified acceptance of homosexuality as … a highly valued expression of human love on a par with heterosexuality.”

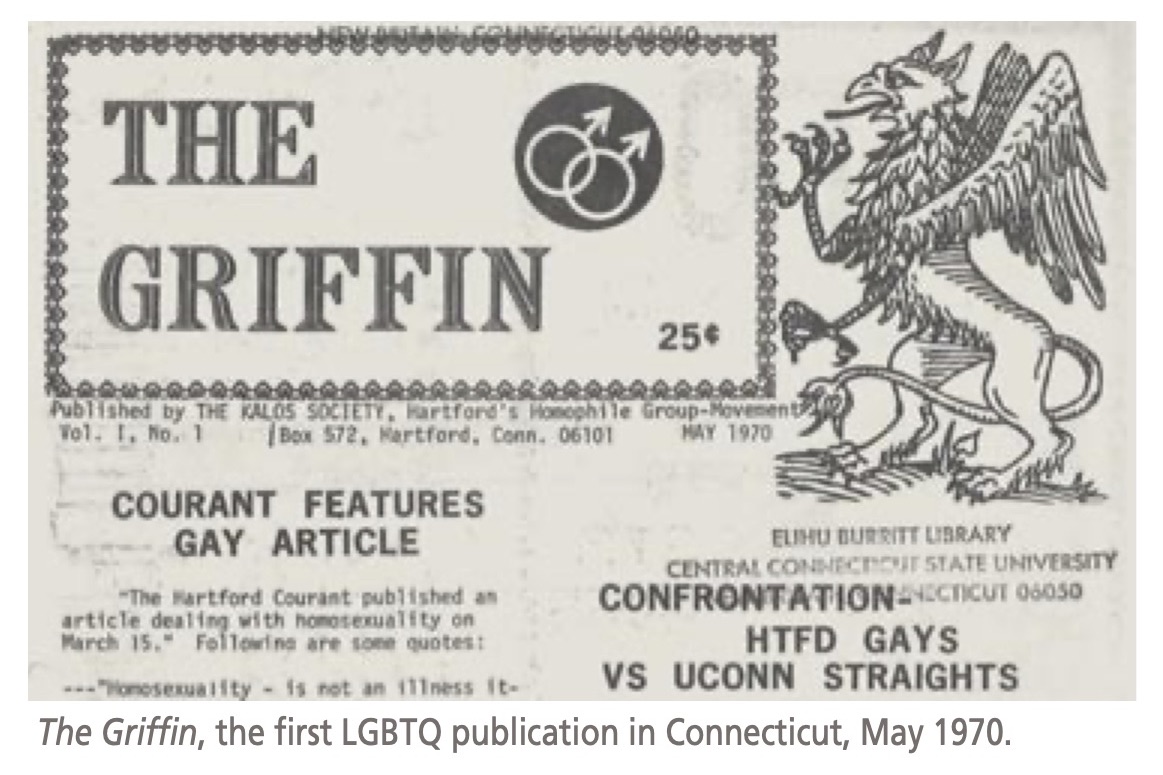

The Griffin folded after a couple of years, and was replaced by The Connexion, which lasted just a few months. But one man understood the need for a consistent community voice, and he wasn’t afraid to use his full name: John Crowley. Crowley turned MCC News into Metroline. By then the state’s gay movement was louder, stronger, and more open. Crowley and Metroline, and Connecticut’s feminist movement, share credit for that. Metroline covered Connecticut’s first gay pride rally on June 26, 1982, when 350 brave people gathered on the grounds of Connecticut’s Old State House.

Another contributor was Gay Spirit Radio, which debuted on WWUH on the campus of the University of Hartford in November 1980. At first, it was run by a collective of gay and lesbian volunteers, many Kalos veterans. Within a year, Keith Brown emerged as the show’s regular host, and for the next three decades he was the distinctive voice of Gay Spirit, every Thursday night at 8:30. The show featured news updates, interviews, music, and more, and also served as a resource guide and calendar of upcoming events.

As the AIDS crisis deepened, keeping the community informed was a matter of life or death. Both Metroline and Gay Spirit provided safer-sex guidelines and encouraged people to take action. A new urgency was rising in the fight for gay rights, including introduction of a gay rights bill. Metroline, of which I became editor in 1989, provided biweekly updates on the legislative progress, and called out those who opposed the bill. The staff brokered a meeting between gay rights activists and the Archdiocese of Hartford. We were at the State Capitol when the bill finally passed in 1991. And I’d finally found the courage to start using my full name in my byline.

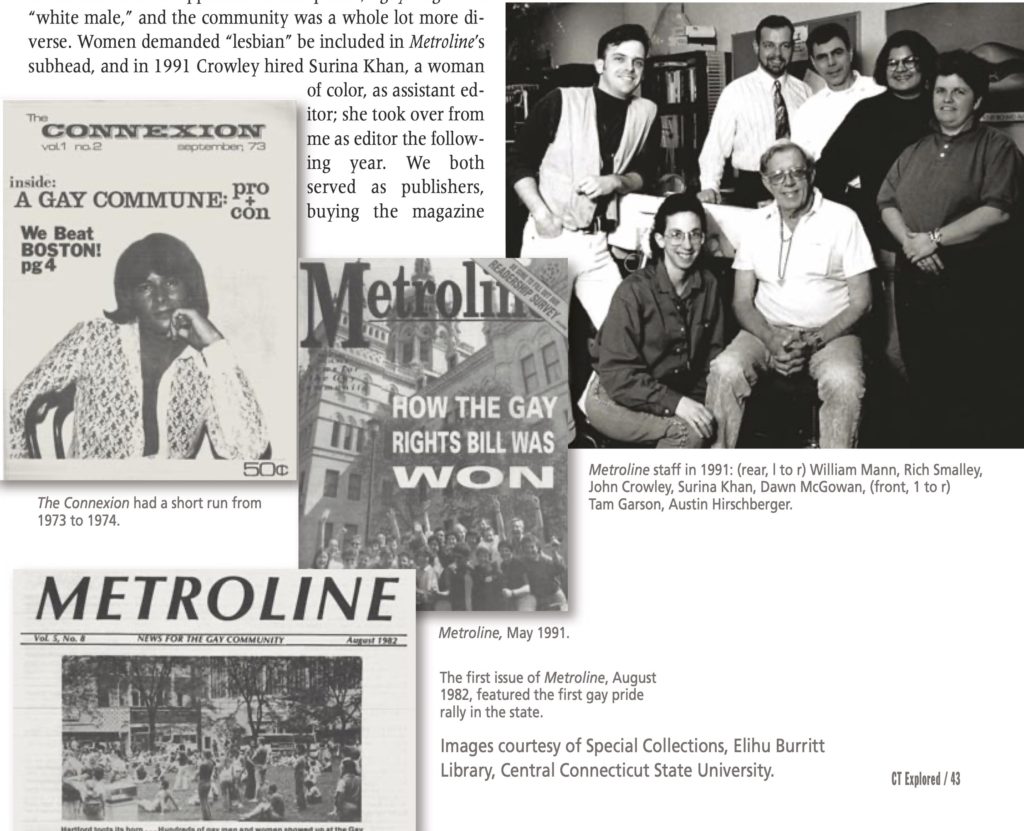

The staff at Metroline was also grappling with internal issues. In its earliest usage, “gay” was meant to include anyone who wasn’t heteronormative, but by the early 1990s, the word’s limits had become apparent. To the public, “gay” signified “white male,” and the community was a whole lot more diverse. Women demanded “lesbian” be included in Metroline’s subhead, and in 1991 Crowley hired Surina Khan, a woman of color, as assistant editor; she took over from me as editor the following year. We both served as publishers, buying the magazine from Crowley in 1993. Our new team decided to advocate against sexism and racism, too; we didn’t have the word “intersectional” yet, but we understood the concept. Eventually, bisexuals and transgender people got the magazine to acknowledge them as the “gay” movement evolved into LGBTQ: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer.

Khan and I sold Metroline in 1995 to pursue our own writing careers, but the magazine continued with the same commitment to community service. By the early 2010s, Metroline was gone, a casualty of the online revolution that doomed many advertisement-reliant publications. But more than 30 years after its founding, Gay Spirit Radio endures, with Keith Brown still at the mic, still making sure the LGBTQ community is informed and inspired.

William Mann is the author of several books about political and film history. He is also an assistant professor of History at Central Connecticut State University.

LISTEN!

Grating the Nutmeg episode 119

GO TO NEXT STORY

Subscribe to receive every issue!